MARK KOSTICH / ISTOCK / GETTY IMAGES PLUS

MARK KOSTICH / ISTOCK / GETTY IMAGES PLUS

Treatment Considerations for Patients With a History of Head and Neck Radiation Therapy

Although treatment of this patient population can be difficult, oral health professionals who provide high-quality care and collaborate interprofessionally with the multidisciplinary oncology team will have the most successful outcomes.

This course was published in the July/August 2023 issue and expires August 2026. The authors have no commercial conflicts of interest to disclose. This 2 credit hour self-study activity is electronically mediated.

AGD Subject Code: 730

Educational Objectives

After reading this course, the participant should be able to:

1. Recognize various oral conditions associated with head and neck radiation therapy (H/N RT).

2. Discuss strategies for managing negative side effects that arise from H/N RT.

3. Provide individualized oral care instructions about common oral symptoms associated with H/N RT.

Patients with head and neck cancer (HNC) comprise approximately 4% of all patients with cancer.1 In the United States, an estimated 66,920 people will be diagnosed with HNC and about 15,400 of those will die in 2023.2 Generally, the survival rate for HNC is increasing, although the exact rate is challenging to determine because of the variability between types.3–5

Radiation therapy (RT) is a common treatment option and is highly effective in the treatment of cancer.6 Dental professionals need to be able to recognize and manage the long-term effects associated with RT. Effective treatment of HNC requires timely referrals and close communication between the dental and oncology teams.

Oral Conditions Related to Radiation Therapy

Oral mucositis is a severely debilitating condition characterized by erythema, edema, and ulcerations of the oral mucosa. It is a common complication of head and neck radiation therapy (H/N RT), as well as other cancer treatment modalities.7

Mucositis can be mild with red, irritated, and swollen tissues or severe with ulcerations covering the oral mucosa. It is very painful and can affect speaking, swallowing, and overall quality of life. Severe mucositis may result in malnutrition, treatment delays, and overall reduction in success of cancer treatment.8

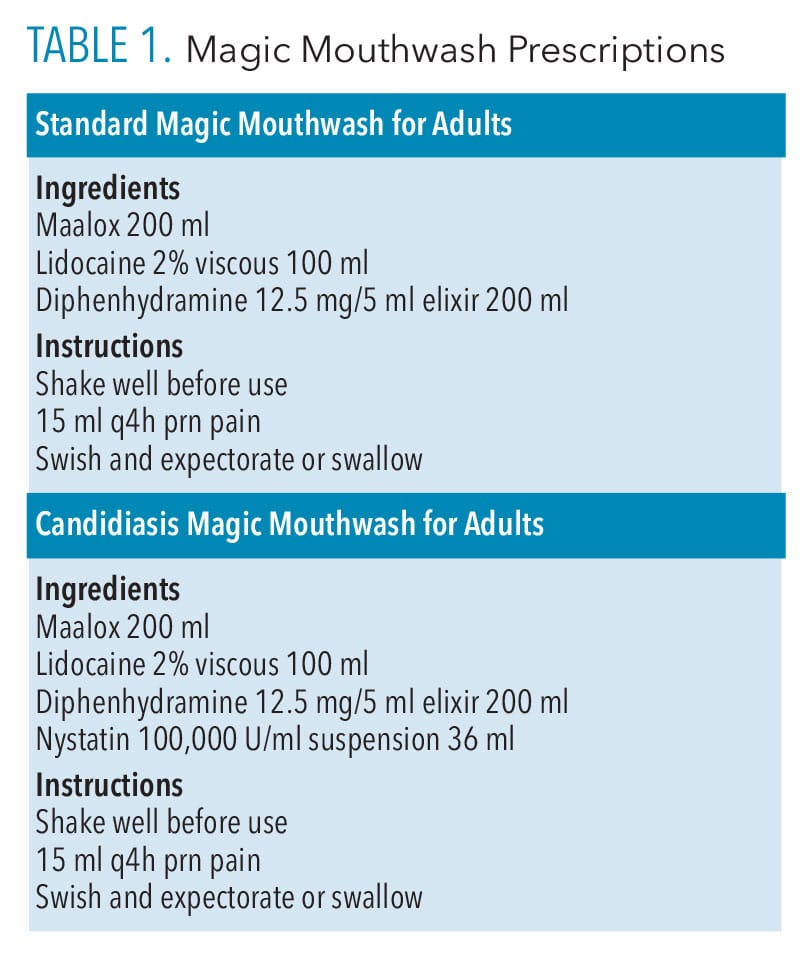

Depending on radiation dosing, symptoms can occur at varying intervals, but often peak toward the completion of treatment and generally begin to improve over several weeks post-RT.9 Treatment options include Magic Mouthwash or Magic Mouthwash with nystatin for patients with concomitant oral candida infection (Table 1).9

Trismus refers to muscle spasms or restriction of the muscles of mastication that hinders patients’ ability to open their mouths. A normal opening should allow the patient to place two or three fingers vertically between their incisors.

Patients may experience trismus during and after treatment, making it difficult for them to eat and perform thorough oral hygiene care.9 This could lead to additional oral and nutritional complications and a significant reduction in quality of life.

Treatment options include exercising three times a day by opening and closing the mouth as far as possible without pain, repeating 20 times or referral to a physical or occupational therapist for additional support.

Xerostomia is very common during and after RT, due to damage to salivary glands from the radiation. RT results in hyposalivation and the feeling of xerostomia. Patients may see improvements during the first year following treatment, but hyposalivation and xerostomia often persist.9 As a result, patients are at increased risk for both periodontal diseases and dental caries and may require additional support for self-care.9 Treatment options include saliva stimulants (containing xylitol), dry mouthrinses, and discontinuing tobacco use (if applicable).

RT causes hyposalivation and xerostomia, which dramatically increase the risk for dental caries. Approximately 29% of patients receiving H/N RT develop radiation-related caries within 3 months of treatment conclusion.10 Radiation caries is highly destructive and rapidly progresses.11 Every effort should be focused on prevention, as the management of severe radiation caries can be difficult.

Additionally, effects of RT alter enamel and dentin, which may compromise the bonding of adhesive dental materials, posing more challenges. Preventive treatment options include nutritional counseling and prescription fluoride products.

Osteoradionecrosis of the jaw (ORN) is one of the most concerning complications of H/N RT. Clinically characterized by exposed necrotic bone within the field of H/N RT, ORN more commonly affects the mandible than the maxilla.12–14

While the risk of ORN is present after any level of radiation exposure, it increases significantly when the patient receives more than 6,000 centigrays (cGy) of radiation and if a triggering event occurs in the radiation field post-RT.15–17 Triggering events include dental extractions, especially mandibular posterior teeth with roots that lie below the mylohyoid line; osseous periodontal surgery; and severe denture sores.14,18

Despite the evolution of RT modalities, ORN continues to pose a therapeutic challenge and its cause remains unclear. ORN lesions can occur years after the RT is concluded so vigilant history and oral examination remain important.

ORN is diagnosed as a clinical presentation of irradiated bone that is nonvital/necrotic and exposed through the overlaying mucosa without healing for a period of 3 months or longer.19 The presentation of early ORN may be asymptomatic, although pain is common if the lesion progresses. Other associated symptoms may include oral malodor, dysgeusia, and food impaction in the area of exposed bone. In severe cases, ORN can result in fistulae, complete devitalization of regions of bone, and pathologic fractures of the jaw.20 ORN lesions typically occur between 4 months and 2 years post-RT and the risk decreases over time, but remains for life.9,18,20

Treatment Considerations

Request for preradiation clearance by the medical oncology team is becoming more common; however, patients with a history of H/N RT frequently present to dental offices with significant dental disease. Managing these patients can be extremely challenging due to the high incidence of oral side effects, restorative dental implications, and limited treatment options. This requires careful assessment and comprehensive treatment planning.

The dental team begins by gathering the following information:

- Thorough medical and dental histories

- Appropriate radiographs (current full-mouth series and panoramic images)

- Complete restorative and periodontal charting including current and proposed restorative treatment and probe depths, recession, mobility, furcation, and bleeding

- Assessment of caries risk. If patients are noted as high risk after using caries management by risk assessment (CAMBRA), nutritional habits should be reviewed, oral hygiene capabilities assessed, a social history including nicotine and tobacco use taken, and a baseline salivary flow level determined.

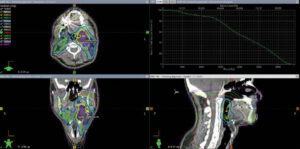

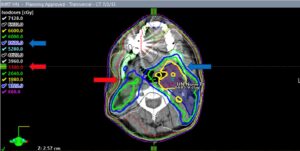

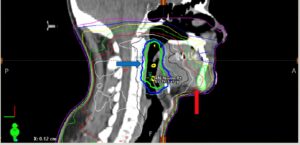

Consultation with the multidisciplinary oncology treatment team follows the comprehensive oral examination. The dental team should request contact information for the assigned nurse to promote continued communication related to white blood cell counts and other labs as well as an electronic copy of the radiation map (Figure 1).

Radiation mapping is a computed-tomography scan with an overlay of the radiation dose. The targeted center of the radiation is noted and the colored rings indicate the dosage working outward from the epicenter. Using the three vantage points provides a clear picture of which structures were affected and to what degree. This is a useful tool to determine what parts of the maxilla, mandible, and salivary glands were in the field of radiation, what the total dose of radiation was, and whether chemotherapy or surgical procedures were involved. This information will be vital if extractions are needed as structures exposed to dosages in excess of 6,000 cGy have a much higher risk of ORN.15

The next step is to consult with patients about their goals. Due to potential negative side effects, treatment recommendations may be different from those for nonradiation patients. This conversation will allow the dental team to consider patients’ needs in the treatment planning process and provide compassion when discussing options that do not align with patients’ goals.

Creating a Comprehensive Treatment Plan

Next, the dental team should create a comprehensive treatment plan prioritized by the urgency of needs. Following is a sequence of addressing treatment needs.

- Improve oral hygiene and stabilize the periodontium. The dental hygienist should evaluate patients’ oral condition prior to beginning treatment. If the oral mucositis is actively painful or trismus is limiting their opening, rescheduling may be necessary.

Provide thorough oral hygiene recommendations including brushing and interdental cleaning as well as management of RT-related oral conditions. Ultra-soft bristle toothbrushes and baking soda/water or warm saltwater rinses may allow for more comfort when the mucositis is flaring. Prescribe 1.1% neutral pH sodium fluoride gel or 0.4% stannous unflavored gel and instruct patient to use at least once daily, preferably at bedtime, without eating, drinking, or rinsing for at least 30 minutes for caries prevention. Products to promote increased salivary flow should be recommended.

- Address active decay. The dentist should also evaluate the oral condition prior to restorative treatment. Trismus can make it challenging to use a handpiece and for the patient to remain open long enough to effectively restore the area. The use of hand instruments and silver diamine fluoride to arrest active decay in combination with resin-modified glass ionomer restorations to seal the damaged structures are good options for post-radiation patients.21–24 Once the trismus improves, conventional restorative options may be considered.

- Address nonrestorable teeth. Nonrestorable teeth may need an alternative treatment recommendation. If extractions carry an excessive risk of ORN due to radiation dosage, endodontic treatment of the nonrestorable teeth and decoronation (removal of the structurally damaged coronal portion of the tooth while leaving the endodontically treated roots in the bone) is an option.25 Prosthetic replacement of missing or decoronated teeth may include fixed partial dentures, tooth-supported removable partial dentures, or complete dentures with soft internal liners.

- All treatment plans must include periodontal care. Patients should have the opportunity to ask questions and provide informed consent to treatment.

Dental Clearance Considerations

Requests for preradiation dental clearance from the medical oncology teams are increasingly common. This allows the dental team to address current dental concerns and plan for potential future problems. This can significantly improve treatment outcomes and quality of life for patients during and after RT.

Dental team members promptly begin by gathering and evaluating the assessments listed above. They will use this information coupled with a clinical evaluation to determine the patient’s overall oral health prognosis and create a comprehensive treatment plan prioritizing urgent treatment needs followed by long-term recommendations to prevent future problems. Treatment plans may be more aggressive with increased extractions due to evidence supporting the best time to extract questionable teeth is before the onset of RT.9,26

If dental extractions or alveoloplasty surgeries are needed, they should be completed at least 14 days prior to RT to allow for time for soft-tissue closure to occur. If possible, complete all restorative dental treatment prior to RT due to discomfort from mucositis and xerostomia during and after RT. If time does not allow for this, the dental team should stabilize the dentition and complete nonextraction restorative care once active RT is complete and mucositis resolves. Tray delivery of daily 10-minute fluoride applications should begin several days prior to RT.

Once the patient begins RT, the dental team should maintain frequent communication. Teledentistry may be used to minimize patient visits to the office. Patient-captured images of oral tissue can be very helpful in determining the need for an in-person visit. Three-month recare appointments are recommended, but flexibility is required.

Conclusion

Patients who receive H/N RT can generally expect to live a long life after diagnosis and treatment of the cancer. Dental professionals will increasingly treat patients who have received RT. While treatment can be challenging, dental team members can be successful if they strive to provide high-quality care and collaborate interprofessionally with the multidisciplinary oncology team.

Case Study

Mike is a 58-year-old man with a history of squamous cell carcinoma of the left tonsil. Treatment consisted of surgical resection of the tumor, neck dissection of affected nodes and structures, and head and neck radiation therapy (H/N RT),in excess of 6,000 cGy. Seven years later, the patient was referred to the dental oncology clinic by his general dentist for evaluation of teeth #29 and #30 (Figure 1).

Thorough medical and dental histories followed by comprehensive oral examination and radiographic analysis were completed (Figure 2). The dental diagnosis revealed a lesion of external root resorption on the buccal of tooth #29 and the mesiolingual of tooth #30.

The tumor received the heaviest radiation dose of 6,885 cGy at the target point (Figure 3). Teeth #29 and #30 are located in the right mandible within the red line on the radiation map indicating they received a smaller dose of 3,300 cGy (red arrow on Figures 3 through 5), which is significant, but below the 6,000 cGy threshold.

Due to the patient’s desire to retain his teeth, root canal therapy was completed on #29; however, the patient developed a submandibular space infection after this procedure. The interdisciplinary medical team convened to review the new dental recommendations and associated risks. Although there is a potential risk for osteoradionecrosis of the jaw (ORN) following the extraction of #29 and #30, a potential life-threatening risk of a new submandibular space infection is present. Mike decided to extract both teeth, because he’d rather deal with the risk of ORN than always worrying that another submandibular space infection would occur.

The teeth were extracted as atraumatically as possible. The 14-day post-operative check was within normal limits and the patient was comfortable and pleased. Mike is without signs or symptoms of ORN (Figure 6) and maintains a 3-month recare schedule.

Although the physical response of a patient treated by H/N RT can be unpredictable, this case illustrates the ability to have successful clinical outcomes even if invasive treatment is required. Gathering and evaluating all relevant information provided by patients and their medical team, as well as thorough data collection in the dental office, led to the successful result.

References

- Cancer.Net. Head and Neck Cancer — Introduction. Available at: cancer.net/cancer-types/head-and-neck-cancer/introduction. Accessed July 27, 2023.

- Cancer.Net. Head and Neck Cancer — Statistics. Available at: cancer.net/cancer-types/head-and-neck-cancer/statistics. Accessed July 27, 2023.

- Pulte D, Brenner H. Changes in survival in head and neck cancers in the late 20th and early 21st century: a period analysis. Oncologist. 2010;15:994-1001.

- Marur S, D’Souza G, Westra WH, Forastiere AA. HPV-associated head and neck cancer: a virus-related cancer epidemic. Lancet Oncol. 2010;11:781-789.

- Forte T, Niu J, Lockwood GA, Bryant HE. Incidence trends in head and neck cancers and human papillomavirus (HPV)-associated oropharyngeal cancer in Canada, 1992–2009. Cancer Causes Control. 2012;23:1343-1348.

- Chow LQM. Head and neck cancer. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:60-72.

- Bell A, Kasi A. Oral Mucositis. Treasure Island, Florida: StatPearls Publishing; 2023.

- Zheng Z, Zhao X, Zhao Q, et al. The effects of early nutritional intervention on oral mucositis and nutritional status of patients with head and neck cancer treated with radiotherapy. Front Oncol. 2021;10.

- Sroussi HY, Epstein JB, Bensadoun RJ, et al. Common oral complications of head and neck cancer radiation therapy: mucositis, infections, saliva change, fibrosis, sensory dysfunctions, dental caries, periodontal disease, and osteoradionecrosis. Cancer Med. 2017;6:2918-2931.

- Dezanetti JMP, Nascimento BL, Orsi JSR, Souza EM. Effectiveness of glass ionomer cements in the restorative treatment of radiation-related caries — a systematic review. Support Care Cancer. 2022;30:8667-8678.

- Gupta N, Pal M, Rawat S, et al. Radiation-induced dental caries, prevention and treatment – A systematic review. Natl J Maxillofac Surg. 2015;6:160-166.

- Singh A, Huryn JM, Kronstadt KL, Yom SK, Randazzo JR, Estilo CL. Osteoradionecrosis of the jaw: A mini review. Front Oral Health. 2022;3:980786.

- Jham BC, Reis PM, Miranda EL, et al. Oral health status of 207 head and neck cancer patients before, during and after radiotherapy. Clin Oral Investig. 2008;12:19-24.

- Tsai CJ, Hofstede TM, Sturgis EM, et al. Osteoradionecrosis and radiation dose to the mandible in patients with oropharyngeal cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol. 2013;85:415-420.

- Alfouzan AF. Radiation therapy in head and neck cancer. Saudi Med J. 2021;42:247-254.

- Kuo TJ, Leung CM, Chang HS, et al. Jaw osteoradionecrosis and dental extraction after head and neck radiotherapy: A nationwide population-based retrospective study in Taiwan. Oral Oncol. 2016;56:71-77.

- Jawad H, Hodson NA, Nixon PJ. A review of dental treatment of head and neck cancer patients, before, during and after radiotherapy: part 1. Br Dent J. 2015;218:65-68.

- Lyons A, Ghazali N. Osteoradionecrosis of the jaws: current understanding of its pathophysiology and treatment. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2008;46:653-660.

- Pitak-Arnnop P, Sader R, Dhanuthai K, et al. Management of osteoradionecrosis of the jaws: An analysis of evidence. Eur J Surg Oncol EJSO. 2008;34:1123-1134.

- Yang D, Zhou F, Fu X, et al. Symptom distress and interference among cancer patients with osteoradionecrosis of jaw: A cross-sectional study. Int J Nurs Sci. 2019;6:278-282.

- Palmier NR, Migliorati CA, Prado-Ribeiro AC, et al. Radiation-related caries: current diagnostic, prognostic, and management paradigms. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol. 2020;130:52-62.

- Dezanetti JMP, Nascimento BL, Orsi JSR, Souza EM. Effectiveness of glass ionomer cements in the restorative treatment of radiation-related caries — a systematic review. Support Care Cancer. 2022;30:8667-8678.

- Hendre AD, Taylor GW, Chávez EM, Hyde S. A systematic review of silver diamine fluoride: Effectiveness and application in older adults. Gerodontology. 2017;34:411-419. d

- Gupta N, Pal M, Rawat S, et al. Radiation-induced dental caries, prevention and treatment – A systematic review. Natl J Maxillofac Surg. 2015;6:160.

- Beech N, Robinson S, Porceddu S, Batstone M. Dental management of patients irradiated for head and neck cancer. Aust Dent J. 2014;59:20-28.

- Lanzós I, Herrera D, Lanzós E, Sanz M. A critical assessment of oral care protocols for patients under radiation therapy in the regional University Hospital Network of Madrid (Spain). J Clin Exp Dent. 2015;7:e613-e621.

From Dimensions of Dental Hygiene. July/August 2023; 21(7):32-35.