WDCN/UNIV. COLLEGE LONDON/SCIENCE SOURCE

WDCN/UNIV. COLLEGE LONDON/SCIENCE SOURCE

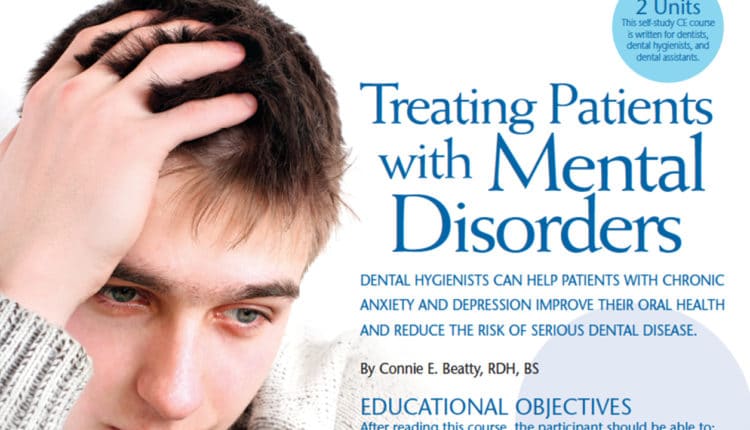

Treating Patients with Mental Disorders

Dental hygienists can help patients with chronic anxiety and depression improve their oral health and reduce the risk of serious dental disease.

This course was published in the April 2013 issue and expires April 2016. The author has no commercial conflicts of interest to disclose. This 2 credit hour self-study activity is electronically mediated.

EDUCATIONAL OBJECTIVES

After reading this course, the participant should be able to:

- Discuss the signs and symptoms of anxiety and depressive disorders.

- Identify the association between anxiety/depression and oral health.

- List recommendations for clinical oral care.

Once viewed as an unspoken or “taboo” issue, mental health disorders are now recognized as legitimate medical conditions, affecting almost 50% of the United States’ population.1 The cost of treating those affected totals more than $300 billion per year, making mental illness the second leading cause of lifetime disability, behind only cardiovascular disease.2 While mental health disorders can present among all types of patient populations, racial/ethnic/minority groups and those of low socioeconomic status are at greatest risk.2

Clinical anxiety and depression disorders are the most common mental illnesses.2 The effects of these disorders are exacerbated by the frequent presence of one or more chronic systemic conditions, which, in turn, raises the risk of additional health problems.2 As mental health affects all aspects of patients’ lives, it is no surprise that clinical depression/anxiety produce oral health complications.

BACKGROUND

In 1999, the US Department of Health and Human Services released “Mental Health: A Report of the Surgeon General.”2 Three years later, a supplemental report detailed the burden of mental health on culture, race, and ethnicity.3 These reports discussed the fact that the four largest minority groups in the US (African Americans, American Indians and Alaskan Natives, Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders, and Hispanic Americans) represent 30% of the country’s population, yet they experience the greatest unmet health needs, especially those related to mental health.2,3

Mental health remains a key public health issue in the US. The Surgeon General’s reports defined mental health as “the successful performance of mental functions in terms of thought, mood, and behavior.”2 The reports further explained that mental health affects self-esteem and the ability to maintain emotional stability, successfully communicate, and learn.2 Simply put, mental health affects all aspects of life.

More than half of individuals with anxiety and depression are diagnosed during childhood or adolescence. The remaining half are not detected until after age 30.4,5 Clinical anxiety and depressive disorders affect both men and women, but are more common among women.2,3

ANXIETY AND DEPRESSION DEFINED

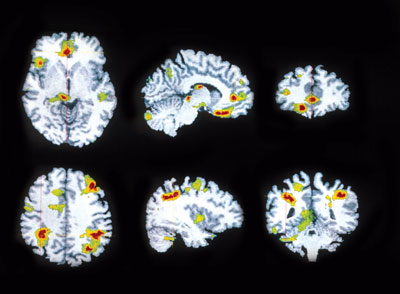

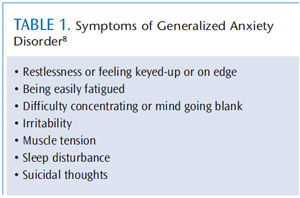

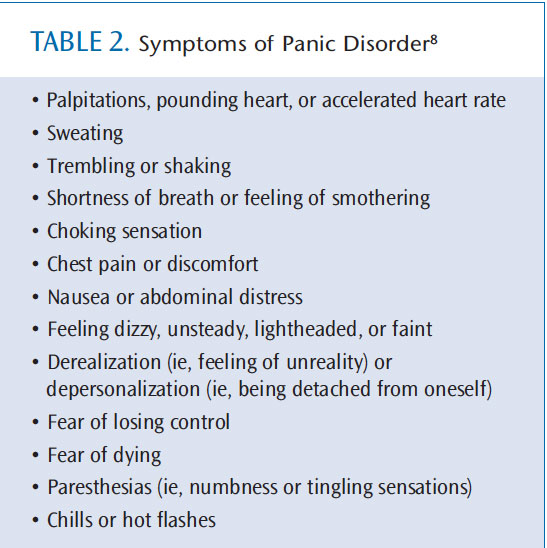

Anxiety disorders are similar to depressive disorders in how they are treated, but exhibit markedly different symptoms. As defined by the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH), individuals suffering from clinical anxiety struggle with overwhelming, debilitating fear and distress for months at a time. Anxiety can cause heart palpations, excessive sweating, labored or increased rate of breathing, dilated pupils, and muscle tension.6 Clinical anxiety disorders can be related to a specific event or situation, such as phobias or post-traumatic stress disorder. They may also present as panic disorders, generalized anxiety disorder, or obsessive-compulsive disorder (Figure 1).7 Table 1 and Table 2 list the symptoms of generalized chronic anxiety and panic disorder, respectively.8

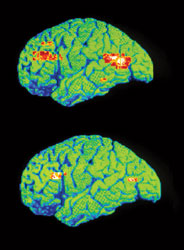

According to the NIMH, clinical depression is a reduction in the amount of neurotransmitters found in the brain, specifically norepinephrine and serotonin (Figure 2).9 Differential diagnoses for depression are based on the duration and extent of symptoms. The most severe form of depression is major depressive disorder, a condition characterized by a continuous state of disinterest accompanied by side effects that significantly impair or inhibit the ability to function and perform activities of daily living. Commonly seen symptoms include noticeable changes in appetite and weight (loss or gain), inability to or excessive sleep patterns, loss of interest in sexual activity, and loss of desire to engage in activities once considered enjoyable and pleasurable.6,9 The duration of symptoms is not relative to the diagnosis of major depressive disorder because it is identified by the severity of symptoms alone.

Another type of depression, dysthymic disorder, is characterized by mildly inhibiting symptoms and length of affliction, usually 2 years or longer. The third category of depressive disorders is minor depression, which is a milder, shorter version of major depression. The extent and duration of symptoms in minor depression vary and it may manifest as post-partum depression, psychotic depression, and seasonal affective disorder.9 Treating depression is complex. While pharmaceuticals are often health care providers’ regimen of choice, finding the right drug and dosage is time-consuming.2,7,10 Often, medication will be recommended in conjunction with psychotherapy from a licensed counselor or psychologist.2,7,10 As treatment modalities are discussed and pursued, health care providers need to consider the effects on other aspects of patient health.

IMPACT ON SYSTEMIC HEALTH

In years past, it was common to isolate mental illness as different from typical ailments of the body. Mental disorders could not be tested and diagnosed in the same quantitative manner that diabetes or heart disease are detected. With the progression of research, mental health is now recognized as an important component of overall wellness. 2 Mental health disorders often function as a comorbid condition2,3,6,7,9–11 Clinical anxiety and depressive disorders can increase the risk of additional health complications, such as diabetes, cardiovascular disease, obesity, and chronic pain disorders.2,3,6,7,9–13

IMPACT ON ORAL HEALTH

Anxiety and depressive disorders, along with the drugs used to treat them, can affect oral health. For more than a decade, research has indicated that individuals with clinical anxiety and depression experience a higher prevalence of tooth loss, dental caries, periodontal diseases, xerostomia, and high plaque index. Less common oral side effects include bruxism, candidiasis, dysphagia, and burning mouth syndrome.1,11,14–18 The prevalence of tooth loss and periodontal diseases among those with chronic anxiety or depression may stem from the neglect of oral self-care as patients struggle to deal with their illness. During periods of stress, toothbrushing frequency often declines.18,19 The ravaging effects of xerostomia as a pharmaceutical side effect not only exacerbate the caries risk due to the absence of saliva, but also produce increased counts of Lactobacillus bacteria. 1,11,16,20 Smoking is common among those with mental disorders, and this habit has a distinct correlation to periodontal diseases.16

Researchers have discovered that depression and other stress-invoking factors inhibit the host immune response, increasing the risk of periodontal disease development and progression.18,19 The brain increases cortisol levels in the body when faced with stress. A chronic increase in salivary cortisol levels is associated with an increase in the breakdown of periodontal fibers, proliferation of harmful bacteria in the oral cavity, and an upset of the balance of key cytokine levels that help regulate inflammation within the periodontum.18,19

CURRENT CLINICAL CARE RECOMMENDATIONS

Risk assessment is the first step in promoting health and preventing disease among patients with mental disorders. Clinicians must treat the symptoms of oral disease only after they have addressed the underlying condition causing the clinical signs. Oral health risk factors that can be addressed include history and current presence of active oral disease (periodontal and caries), poor oral hygiene, smoking, medication use, quality and quantity of saliva, presence of disease-specific pathogens, and systemic conditions that threaten the immune system (eg, diabetes, human immunodeficiency virus).21 With thorough examination and the recording of a comprehensive health history, dental professionals can garner a solid understanding of the patient’s condition, its duration, recommended therapy, and current status of the condition (stable or struggling). A drug reference resource should be consulted in order to learn about any possible pharmaceutical side effects.5

Customized education concerning biofilm control and pH regulation should follow the risk assessment. For patients with periodontal disease, simply telling them to floss more is inadequate, and could be construed as insensitive. Dental hygienists may want to suggest the use of interproximal aids and electric oral care devices to help patients improve their self-care. Determining patients’ baseline pH status is imperative. A naturally acidic environment will continually promote demineralization, despite the best oral hygiene interventions.

Clinicians need to discover what strategies will work for individual patients. For example, is chewing xylitol gum throughout the day easier to remember than using two different prescription products twice a day? While prescription products offer tremendous value, especially those formulated for remineralization, patients with unstable mental status may struggle with multiple recommendations. Patients with mental illness should also be seen on a more frequent interval so any oral health problems can be immediately addressed.

RECOMMENDATIONS FOR FURTHER STUDY

Practitioners can expect to encounter men, women, and children on a daily basis who face the struggles of clinical anxiety and depression.1,2 Clinical anxiety disorders tend to be more overt and easily recognized. Depressive conditions, while most commonly characterized by a lack of interest and engagement, often require significant time for symptoms to manifest. Patients with diagnosed anxiety or depression should be considered medically compromised and at higher risk of oral disease. Because the incidence of tooth loss, periodontal diseases, caries, xerostomia, and higher plaque index is notably higher among this population, a proactive preventive strategy based on risk assessment and management can help improve their oral health.

Additional study is needed to continue the development of best practice recommendations for oral health therapy among this population. Research outlining continuing care frequency and its relationship with caries risk management can lead to better oral care of these patients. Further data delineating interactions between mental health therapies and oral health regimens could provide a platform for greater interprofessional collaboration among health care providers. Dental professionals need to be able to recognize the signs and symptoms of clinical anxiety and depression disorders and accurately address their relationship to oral health in order to provide the highest quality of care.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

The author wishes to thank Christine Nathe, RDH, MS, for her assistance with this manuscript

REFEERENCES

- Okoro CA, Strine TW, Eke PI, Dhingra SS,Balluz LS. The association between depression and anxiety and use of oral health services and tooth loss. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2012;40:134–144.

- Office of the Surgeon General. Mental Health:A Report from the Surgeon General. 1999.Available at: www.profiles.nlm.nih.gov/ps/access/NNBBHS.pdf. Accessed March 5, 2013.

- Office of the Surgeon General. Mental Health:Culture, Race, and Ethnicity. A Supplement to Mental Health: A Report of the Surgeon General Available at: www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/ books/NBK44243. Accessed March 5, 2013.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.Depression: Surveillance Data Sources. Available at: www.cdc.gov/mentalhealth/data_stats/depression.htm. Accessed March 5,2013.

- McGorry PD, Purcell R, Goldstone S,Amminger GP. Age of onset and timing of treatment for mental disorders and substance abuse: implications for preventive strategies and models of care. Curr Opin Psych. 2011;24:301–306.

- Little J, Falace D, Miller C, Rhodus N. Dental Management of the Medically Compromised Patient. 7th ed. St. Louis: Mosby Elsevier; 2008:488–530

- National Institute of Mental Health. Anxiety Disorders. Available at: www.nimh.nih.gov/health/publications/anxietydisorders/introduction.shtml. Accessed March 5, 2013.

- Yates WR, Bienenfeld D. Anxiety disorders clinical presentation. Available at: emedicine.medscape.com/article/286227-clinical. AccessedMarch 5, 2013.

- National Institute of Mental Health.Depression. Available at: www.nimh.nih.gov/health/publications/depression/depressionbooklet.pdf. Accessed March 5, 2013.

- National Institute of Mental Health. Mental Health Medications. Available at: www.nimh.nih.gov/health/publications/mental-healthmedications/index.shtml. Accessed March 5,

- Clark DB. Dental care for the patient with schizophrenia. Canadian Journal of Dental Hygiene. 2008;42(1):17–24.

- Hsu YM, Su LT, Chang HM, Sung FC, Lyu SY,Chen PC. Diabetes mellitus and risk of subsequent depression: a longitudinal study. IntJ Nurs Stud. 2012;49:437–444.

- Huang CY, Chi SC, Sousa VD, Wang CP, PanKC. Depression, coronary artery disease, type 2 diabetes, metabolic syndrome and quality of life in Taiwanese adults from a cardiovascular department of a major hospital in Southern Taiwan. J Clin Nurs. 2011;20:1293–1302.

- Cury PR, Araújo VC, Canavez F, Furuse C,Araújo NS. Hydrocortisone affects the expression of matrix metallo proteinases (MMP-1, -2, -3, -7,and -11) and tissue inhibitor of matrixmetalloproteinases (TIMP-1) in human gingival fibroblasts. J Periodontol. 2007; 78:1309–1315.

- Friedewald VE, Kornman KS, Beck JD, et al.The American Journal of Cardiology and Journal of Periodontology editors’ consensus: periodontitis and atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease. J Periodontol. 2009;80:1021–1032.

- Matevosyan NR. Oral health of adults with serious mental illnesses: a review. Community Ment Health J. 2010;46:553–562.

- Persson K, Axtelius B, Soderfeldt B, Ostman M. Monitoring oral health and dental attendance in an outpatient psychiatric population. J Psychiatr Ment Health Nurs. 2009;16:263–271.

- Peruzzo DC, Benatti BB, Ambrosano GM, e tal. A systematic review of stress and psychological factors as possible risk factors for periodontal disease. J Periodontol. 2007;78:1491–1504.

- Rai B, Kaur J, Anand SC, Jacobs R. Salivary stress markers, stress, and periodontitis: a pilot study. J Periodontol. 2011;82:287–292.

- Boyce WT, Den Besten PK, Stamperdahl J, et al. Social inequalities in childhood dental caries: the convergent roles of stress, bacteria and disadvantage. Soc Sci Med. 2010;71:1644–1652.

- Tolle SL. Periodontal and risk assessment. In:Darby ML, Walsh MM, eds. Dental Hygiene Theory and Practice. 3rd ed. St. Louis: Saunders Elsevier. 2010;305–347.

From Dimensions of Dental Hygiene. April 2013; 11(4): 58–61.