Treatment Strategies for Patients with Traumatic Brain Injury

Individualized care provided with patience, compassion, and empathy is necessary to safely and effectively treat this patient population.

This course was published in the April 2013 issue and expires April 2016. The author has no commercial conflicts of interest to disclose. This 2 credit hour self-study activity is electronically mediated.

EDUCATIONAL OBJECTIVES

After reading this course, the participant should be able to:

- Define traumatic brain injury (TBI) and its effects on health and function.

- List the clinical manifestations of TBI, as well as treatment recommendations.

- Identify the most frequently used medications in this patient population and their side effects.

- Discuss the evidence-based recommendations for treating patients with TBI.

Traumatic brain injury (TBI) is a significant health problem in the United States, with approximately 1.7 million Americans experiencing head injuries each year.1 Whether resulting from trauma or injury,2,3 the damage can be confined to one area of the brain (focal) or may involve multiple areas of the brain (diffuse).1,2 A closed head injury can be caused by a violent blow or jolt to the head that does not penetrate the skull, causing the brain to collide with the inside of the skull, whereas a penetrating head injury occurs when an object pierces the skull and enters the brain tissue.2

Adolescent males and young adults are at the greatest risk of TBI, along with men and women over age 75 and children age 5 and younger.1,2 Approximately 1 million people with TBI are treated in emergency rooms each year with an estimated 50,000 deaths and 230,000 hospitalizations.2 Survivors of TBI are often left with significant cognitive, behavioral, and communicative disabilities or long-term medical complications resulting in the permanent need for assistance with performing daily activities.2 Between initial treatment for those with TBI and caring for TBI survivors, head injuries cost the United States more than $76.5 billion a year.1 According to the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke, a division of the National Institutes of Health, there is greater understanding today than ever before of the healthy brain and how it responds to trauma, although there is still much to learn about how to reverse brain damage resulting from TBI.2

Symptoms of a TBI ultimately depend on the extent of damage to the brain and can be mild, moderate, or severe. Complications vary based on the severity and location of the injury, as well as the age and general health of the patient.2,4 Long-term disability is dependent on the severity of the injury.3 Common disabilities resulting from TBI include problems with cognition (which includes memory, thinking, and reasoning), sensory processing, communication, and behavioral or mental health problems.2 These disabilities can impact oral health by creating difficulties with managing selfcare, dexterity issues, oral trauma from the TBI itself or self-injurious behaviors, gastroesophageal reflux disease, bruxism, and difficulty swallowing.5,6

With more than 5 million Americans having experienced a TBI that affects their ability to perform activities of daily living, dental hygienists may encounter this patient population in the operatory.2 Dental hygienists should be prepared to treat these patients appropriately with knowledge, compassion, and skill.

CLINICAL IMPLICATIONS AND TREATMENT CONSIDERATIONS

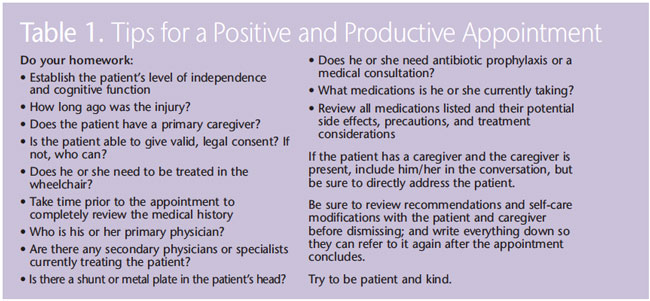

No two brain injuries are exactly alike.4 Therefore, each patient’s level of independence and cognitive function must be assessed prior to providing oral health care, and a thorough health history review must be performed.7 A medical consultation may be completed with the patient’s physician if necessary. Table 1 lists additional tips for ensuring a successful appointment.

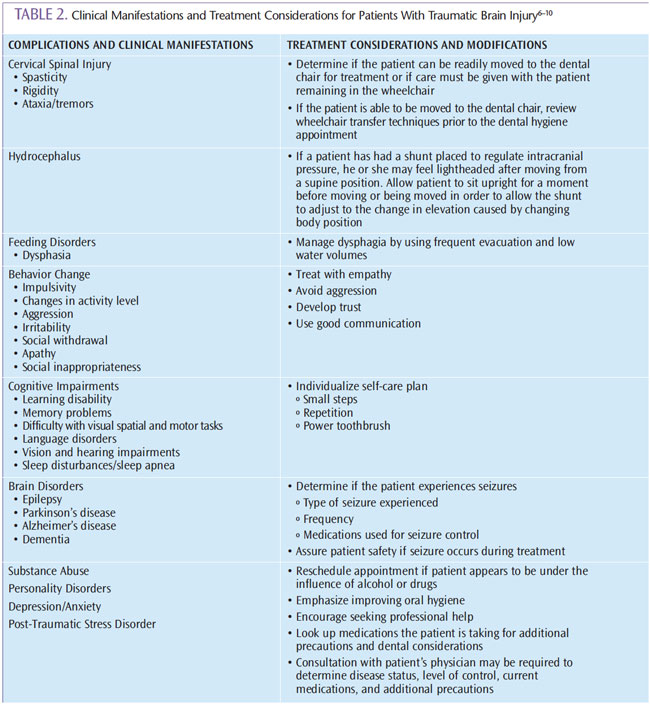

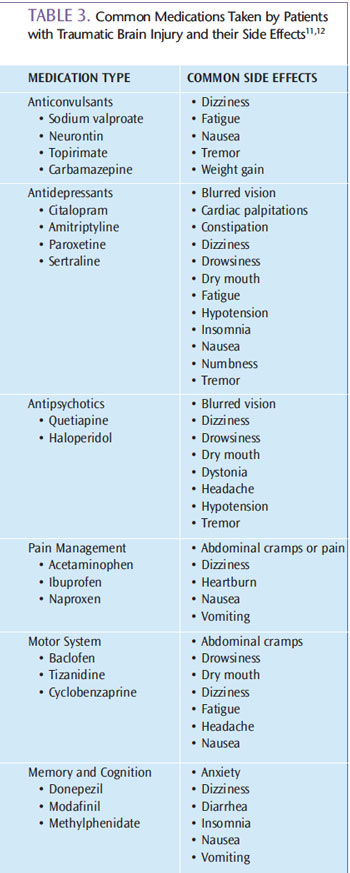

Table 2 summarizes several common clinical manifestations of TBI with corresponding treatment considerations and modifications.6–10 Patients may manifest multiple symptoms of brain dysfunction and impairment simultaneously, and several treatment modifications may need to be made.4,6 Additionally, patients may be taking several medications for treatment of symptoms, including antidepressants, antipsychotics, anticonvulsants, anti-hypertensives, stimulants, and muscle relaxants, among others.6 Table 3 includes common medications taken by patients with TBI and their side effects.11,12 The most frequent side effects include xerostomia, gingival hyperplasia, and changes in heart rate and blood pressure.6 Monitoring vital signs at each appointment is particularly relevant when treating patients with a history of TBI.

Special oral health care is indicated, as individuals with TBI are not always capable of carrying out typical patient-centered obligations. 5 Extra support is needed because they often depend on others to make dental care decisions for them, assist with making and keeping appointments and making payments, provide transportation to and from the dental office, and perform or assist with daily oral hygiene.5 As a result, additional appointment time is often needed to complete treatment.5

As with any other special needs patient population, individuals with TBI need to be treated with empathy, knowledge, and skill.5 Considering the patient’s comfort and safety needs is also paramount. The University of Washington Dental Education in the Care of Persons with Disabilities Program suggests several approaches. A mouthguard for bruxism or self-injurious behaviors should be made for the patient if indicated. Dental hygienists also need to be prepared to act appropriately in the event of a seizure. The deleterious effects of xerostomia can be mitigated with saliva substitutes or stimulants; education about diet and nutrition; xylitol mints, lozenges, or gum to stimulate salivary flow; and use of a prescription-strength fluoride before bedtime.6,13 Mints, gums, and lozenges should only be recommended if the patient is not at increased risk of choking. In addition to the use of a fluoride at home, the American Dental Association Council on Scientific Affairs also recommends a professionally-applied fluoride varnish at 3-month intervals as a caries prevention technique for patients at high risk of decay, such as those with poor self-care, physical or mental disability, and/or medication-induced xerostomia.14

RESEARCH-BASED RECOMMENDATIONS

Limited information exists regarding oral health and patients with TBI. However, some studies have been conducted regarding rehabilitative therapies to improve memory, which may be utilized as part of a program to aid patients with TBI in remembering to perform daily oral hygiene activities or schedule and remember appointments for oral health care.15 Patients with TBI may not have the ability to accurately estimate time, which may make performing oral hygiene tasks, such as brushing for at least 2 minutes, difficult.16 Many power toothbrushes have 2-minute timers that could help. Studies have found that using devices, such as pagers or mobile phones with alarms, may be effective in prompting certain behaviors, which could be expanded to include oral hygiene practices. Prompting behavior may not be as effective in patients with severe TBI who require 24-hour care.17,18

Though studies are limited regarding oral health education in patients with TBI, one study demonstrated that self-care instruction was effective in reducing the plaque scores of patients with TBI.19 Therefore, patient education should be part of comprehensive dental care for those with head injuries.

CONCLUSION

As health care professionals, dental hygienists need know how to treat patients with TBI safely, effectively, and in a respectful and caring manner. Planning ahead and implementing management considerations and techniques, along with an attitude of patience, caring, and compassion, will benefit both the patient and the clinician. When providing care, it is important to keep in mind that TBI manifestations and complications vary greatly depending on the extent, location, and severity of the brain injury; therefore, every patient should be treated in an individualized manner that is appropriate for his or her level of independence and cognitive function.

REFERENCES

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Injury prevention and control: Traumatic brain injury. Available at: www.cdc.gov/TraumaticBrainInjury/index.html. Accessed March 25, 2013.

- National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke. Traumatic Brain Injury: Hope Through Research. Available at: www.ninds.nih.gov/disorders/tbi/detail_tbi.htm. Accessed March 25, 2013.

- Heegaard W, Biros M. Traumatic brain injury. Emerg Med Clin North Am. 2007;25:655–678.

- Brain Injury Association of America. Living With Brain Injury. Available at: www.biausa.org/living-with-brain-injury.htm.Accessed March 25, 2013.

- Stiefel DJ. Dental care considerations for disabled adults. Spec Care Dentist. 2002;22(Suppl):26S–39S.

- University of Washington Dental Education in the Care of Persons with Disabilities Program. Oral Health Fact Sheet for Dental Professionals: Adults with Traumatic BrainInjury. Available at: www.dental.washington.edu/sites/default/files/departments/spec_need_pdfs/TBI-Adult.pdf. Accessed March 25, 2013.

- Kleiman C. Treating returning soldiers with a traumatic brain injury. Available at: www.towniecentral.com/Hygienetown/Article.aspx?aid=3060. Accessed March 25, 2013.

- National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research. Wheelchair Transfer: A Health Care Provider’s Guide. Available at: www.nidcr.nih.gov/OralHealth/Topics/DevelopmentalDisabilities/WheelchairTransfer.htm. Accessed March 25, 2013.

- Toporek C, Robinson K. Hydrocephalus Center: How Shunts Work. Available at: www.oreilly.com/medical/hydrocephalus/news/how_work.html. Accessed March 25, 2013.

- Little JW, Falace DA, Miller CS, Rhodus NL. Dental Management of the Medically Compromised Patient. 7th ed. St. Louis: Mosby Elsevier; 2008.

- Center of Excellence for Medical Multimedia. TBI Medication Chart. Available at: www.traumaticbraininjuryatoz.org/Moderateto-Severe-TBI/Treatment-Stages-of-Moderate-to-Severe-TBI/TBI-Medication-Chart.aspx. Accessed March 25, 2013.

- Jeske, AH. Mosby’s Dental Drug Reference. 10th ed. St. Louis: Elsevier Mosby; 2012.

- Rethman MP, Beltrán-Aguilar ED, Billings RJ, et al. Nonfluoride caries preventive agents: Executive summary of evidence-based clinical recommendations. J Am Dent Assoc. 2011;142:1065–1071.

- American Dental Association Council on Scientific Affairs. Professionally applied topical fluoride: evidence-based clinical recommendations. J Am Dent Assoc. 2006;137:1151–1159.

- Shum D, Fleming J, Gill H, Gullo MJ, Strong J. A randomized controlled trial of prospective memory rehabilitation in adults with traumatic brain injury. J Rehabil Med. 2011;43:216–223.

- Anderson JW, Schmitter-Edgecombe M. Recovery of time estimation following moderate to severe traumatic brain injury. Neuropsychology. 2011;25:36–44.

- Stapleton S, Adams M, Atterton L. A mobile phone as a memory aid for individuals with traumatic brain injury: A preliminary investigation. Brain Inj. 2007;21:401–411.

- Wilson BA, Emslie H, Quirk K, Evans J, Watson P. A randomized control trial to evaluate a paging system for people with traumatic brain injury. Brain Inj. 2005;19:891–894.

- Zasler ND, Devany CW, Jarman AL, Friedman R, Dinius A. Oral hygiene following traumatic brain injury: a programme to promote dental health. Brain Inj. 1993;7:339–345.

From Dimensions of Dental Hygiene. April 2013; 11(4): 62–66.