Tips to Effectively Educate Caregivers Regarding Non-Nutritive Sucking

This oral habit can cause long-lasting, negative effects on oral and systemic health.

This course was published in the February 2023 issue and expires February 2026. The authors have no commercial conflicts of interest to disclose. This 2 credit hour self-study activity is electronically mediated.

AGD Subject Code: 430

EDUCATIONAL OBJECTIVES

After reading this course, the participant should be able to:

- Discuss the development of non-nutritive sucking habits (NNSH) and their negative effects on oral health.

- Identify strategies for educating parents/caregivers about NNSH.

- Explain the role of oral health professionals in preventing and addressing NNSH.

Non-nutritive sucking in children is a common habit used to calm and comfort that can, in certain instances, result in long-term or irreversible craniofacial abnormalities. Feeding habits, such as breastfeeding and bottle sucking, are nutritive sucking habits,1 while thumb or digit sucking, pacifier use, and sucking on toys or blankets are non-nutritive sucking habits (NNSH).2

The impact of prolonged NNSH can adversely affect palatal, facial, and speech development; occlusion; and oronasopharyngeal structure and function.3,4 NNSH may disrupt regular respiratory patterns and result in palatal defects due to the repetitive pressure on the developing palatine bone.4–6 Understanding why certain NNSH occur and how best to provide oral hygiene instruction for parents/caregivers to prevent negative oral health effects is key to successful patient outcomes.

Development and Prevalence

NNSH are prevalent worldwide and present among all socioeconomic statuses, as infants have inherent sucking reflexes that begin prior to birth.

Parents/caregivers often introduce pacifiers to infants to help soothe them.2 Children may associate digit-sucking with positive stimuli connected to food intake or contact with parents/caregivers.

Research suggests sucking behaviors are inherently driven but may persist due to psychological needs.2,7 What starts as a physiological behavior can turn into a detrimental habit if it persists past age 4. In early infant life, thumb-sucking and pacifier use provide oral satisfaction by acting as a substitute for a mother. Habits that persist to the ages of 7 and 8, however, may suggest the child is experiencing a lack of affection.7 NNSH are less common in adolescents and adults but can still occur, as they may serve as a fallback in times of anxiety and stress.

Specific etiologies can lead to NNSH. Overprotection, loneliness, pain, isolation, prolonged breast feeding, and feeding practices may lead to an oral habit.8 The duration, frequency, and intensity of NNSH may lead to permanent changes in the dentition.8

Continuous pressure from a digit in the oral cavity can cause changes in the maxillary arch, anterior portion of the mandible, and the palate.8 Valério et al6 found that bottle-fed children had a higher incidence of developing oral habits and nocturnal respiratory insufficiency.

Negative Effects on Oral Health

Occlusion. Non-nutritive sucking exerts a strong force on the dentition and is associated with malocclusion in the primary dentition.1,3 Malocclusion can cause major health issues due to the lack of support for proper oral functions such as speech, mastication, and balance of periodontal structures.6,9 The primary dentition serves as the foundation for permanent dentition when determining space and proper occlusion, thus, early sucking habits impact occlusion and dental arch formation.1,4

Objects, such as fingers or pacifiers, shift tooth and tongue positioning and can cause misalignment of the teeth. Some malocclusions are more common than others, depending on whether the occurrence is in the primary or permanent dentition.

Anterior open bite and posterior crossbite are the most common malocclusions in deciduous teeth,10 with genetics and prolonged NNSH serving as contributing factors. A Brazilian study looked at preschoolers who presented with an anterior open bite malocclusion. This corrected itself as the children aged, which was likely due to the reduction of NNSH.10

Severe malocclusions are linked to pain, difficulty in speech, social disability, and impaired tongue and masticatory function. Children presenting with malocclusions are also more likely to have dental caries, temporomandibular joint (TMJ) disorders, periodontal diseases, and missing teeth.4 Additionally, a misaligned dentition can lead to lengthy and expensive orthodontic treatment and attrition. Malocclusions in the primary dentition are likely to transfer to the secondary dentition if habits continue (Figure 1).

Facial/Palatal. Closed lips with teeth gently together and the tongue resting lightly against the palate is a typical natural facial resting position. NNSH are associated with changing the muscular balance, growth, and development of the craniofacial complex, as they put pressure on the hard palate, leading to disharmony in the growth of orofacial structures, such as maxillary constrictions or a high, vaulted palate.

Research shows that prolonged NNSH are related to a narrow and greater depth of the anterior portion of the palate due to pressure from a pacifier or finger.10 The lack of palatal support from the tongue causes a narrowed shorter maxilla, broader mandible, and posterior crossbite.10,11

A narrowed maxilla prevents proper placement when the upper jaw and mandible come together and can also lead to a constricted airway, with a tongue projecting forward, causing anterior malocclusions and mouth breathing.4 Narrowed dental arches also increase the risk of obstructed airway, sleep apnea, and more malocclusions.

A vaulted palate reduces the amount of space between the teeth and the upper jaw and can lead to speech problems due to improper tongue placement on the palate. Prolonged NNSH are frequently associated with a lower tongue placement, or a tongue protruding between the arches.

Oronasopharyngeal Effects. NNSH can cause a variety of adverse oronasopharyngeal effects. When oral habits go untreated, oral myofunctional disorders (OMD) can result. OMD is defined as a dysfunction of the lips, jaw, tongue, and/or oropharynx that interferes with growth or function and leads to poor facial development.3

Mouth breathing, an OMD present in 50% of young children and common in children with NNSH and malocclusions, promotes xerostomia and gingival inflammation, in addition to causing the mandible to rotate backward and tongue to position inferiorly.4,12 Mouth breathing is harmful in early childhood because it decreases the critical facial growth that occurs with nasal breathing.3 Nasal breathing helps to filter, humidify, and increase the oxygen intake of the air coming into the body.

Nasal breathing is also necessary to maintain proper muscle tone of intra- and extraoral soft tissues, create proper dentofacial development, and allow sufficient breathing to support vital body functions.13 Air entering the naso- and oropharynx is filtered before it reaches the adenoids and tonsils, helping to decrease the risk of infection. The unpurified air passing directly into the naso- and oropharynx without filtering through the nose causes inflammation of the adenoid and tonsil tissue. The overgrowth of this inflamed tissue forces a habit of mouth breathing.

Mouth breathing due to airway obstruction can lead to an improper tongue positioning on the floor of the mouth.4 When breathing, instead of the tongue resting on the palate, the tongue must descend from the palate to allow a passageway for air. When swallowing, the tongue pushes against the anterior teeth. If the tongue is positioned improperly or thrusting is occurring, the orofacial muscles are used for swallowing, rather than the desired muscles of mastication.12

Mouth breathers are also more likely to develop sleep apnea or sleep-disordered breathing.14 Due to improper development caused by NNSH, the tongue may not have enough room in the mouth and can slide back into the airway during sleep.

Providing Parent/Caregiver Education

Oral health professionals are charged with educating parents/caregivers on the types of NNSH, as well as their harmful effects.3 Digit-sucking is an oral habit that most commonly uses the thumb. If thumb-sucking persists, it can cause adverse effects on dentofacial structures.8 Early examination of children’s oral soft tissues, palate, alveolar ridges, and any erupted or erupting teeth is recommended to determine the complications of thumb-sucking.2

Pacifier-sucking is another deleterious oral habit that is slightly easier to arrest than digit-sucking. Before the ages of 2 to 4, pacifier-sucking should be ignored because most children grow out of the habit. By age 3, motivating the child to stop these habits through playtime rewards, reminders, bitter tasting liquids on pacifiers, thumb guards, hand puppets, and oral appliances is advantageous.8

Parents/caregivers can place gloves or socks on a child’s hands before bed, toys can be given to replace a finger or pacifier, and comfort can be provided during times of stress to reduce NNSH. Parents/caregivers should be aware that by ages 2 to 4, all oral habits should be discontinued to prevent lasting harmful repercussions.8

Parents/caregivers should be able to recognize the signs of NNSH, understand why they are an issue, and attempt to arrest the habit(s) early on.5 NNSH can help soothe children or make them feel satisfied, therefore suddenly forcing a child to stop is not recommended.7 To ensure positive results, parents/caregivers should remain supportive and cautious, avoiding dramatization and threats. Praising the child for not engaging in sucking habits, rather than scolding them when there is engagement, is the suggested style of parent/caregiver intervention.

![]() Role of the Dental Hygienist

Role of the Dental Hygienist

Clinicians play an essential role in preparing parents/caregivers to deal with children’s NNSH and in offering treatment options. Educating parents/caregivers on how their child’s habit leads to detrimental effects and suggesting ways to halt the issue can help minimize the duration of NNSH.

Parents/caregivers should be informed that mouth breathing, ankyloglossia, and prolonged NNSH can interfere with dentofacial development.13 Clinicians should gather a thorough health history by asking questions about the habit and looking for physical signs such as deformity of the nails and blisters, or hyperkeratosis resulting in calluses on the thumb.2

Clinicians should also be aware of symptoms of OMD and be knowledgeable on available treatment methods. Orofacial myofunctional therapy (OMT) can improve the proportion of facial structures, facial muscles, and restore orofacial mobility. It can target habits such as thumb-sucking, improper swallowing, and mouth breathing, and can improve symptoms of TMJ disorders, obstructive sleep apnea, and NNSH.14

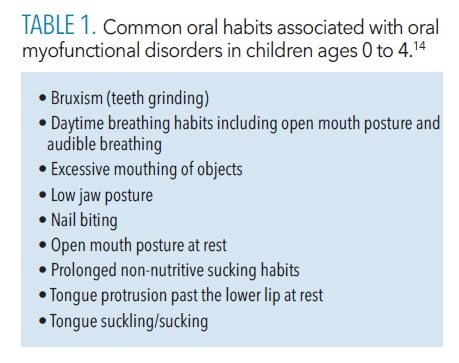

OMT also helps to support perioral and mastication muscles.15 Oral health professionals should be able to recognize signs of orofacial myofunctional habits (Table 1) and recommend oral appliances, counseling, visits to dental offices, and sleep specialists at young age.

Orofacial Myofunctional Therapy

OMT can help treat OMDs that interfere with typical growth, development, and function of orofacial structures. Facial skeletal anomalies can impact orofacial function and change normal chewing, articulation in speech, swallowing, and breathing.16

OMT establishes new neuromuscular patterns, mitigates functional and resting postures, corrects chewing and swallowing patterns, and eliminates deleterious habits.17,18 OMT for tongue thrust include lip, tongue, and cheek exercises to ingrain them into a child’s subconscious.19

A comprehensive evaluation of OMD should assess posture of the head and shoulders, facial symmetry, lip seal, rage of motion of the TMJ, palatal shape, bruxism, anomalies of the dentition, articulation, and voice. It should also include a detailed case history, oral habits, sleep patterns, and airways.16

Sessions of OMT include strengthening the tongue and lip muscles, modifying the swallowing process and resting position of the tongue, and practicing conscious and unconscious habits.18,20 The change of habits modifies sensory perception by the brain, which creates new motor responses and permanent changes.20

Health professionals such as dental hygienists, dentists, orthodontists, speech pathologists, and orofacial myologists with the necessary training, have demonstrated competency in OMT care.16,17,21

Conclusion

Dental professionals play a pivotal role in educating patients about the oral-systemic connection. Clinicians should be well versed on NNSH and related oral-systemic issues to better educate their patients. Current research on the systemic effects of NNSH is limited, demonstrating a need for further studies.

References

- Ling HTB, Sum FHKMH, Zhang L, et al. The association between nutritive, non-nutritive sucking habits and primary dental occlusion. BMC Oral Health. 2018;18:145.

- Staufert Gutierrez D, Carugno P. Thumb sucking. Available at: ncbi.nlm.nih.g/v/books/NBK556112/. Accessed January 19, 2023.

- D’Onofrio L. Oral dysfunction as a cause of malocclusion. Orthod Craniofac Res. 2019;22 Suppl 1(Suppl 1):43–48.

- Mutlu E, Parlak B, Kuru S, Oztas E, Pinar-Erdem A, Sepet E. Evaluation of crossbites in relation with dental arch widths, occlusion type, nutritive and non-nutritive sucking habits and respiratory factors in the early mixed dentition. Oral Health Prev Dent. 2018;17:447–455.

- Warren JJ, Bishara SE, Steinbock KL, Yonezu T, Nowak AJ. Effects of oral habits’ duration on dental characteristics in the primary dentiJ on. J Am Dent Assoc. 2001;132:1685–1726.

- Valério P, Poklepović Peričić T, Rossi A, Grippaudo C, Campos JST, Borges do Nascimento IJ. The effectiveness of early intervention on malocclusion and its impact on craniofacial growth: a systematic review. Contemp Pediatr Dent. 2021;2:72–89.

- Levrini L, Tettamanti L, Tagliabue A, Caprioglio A. Invisalign teen for thumb-sucking management. A case report. Eur J Paediatr Dent. 2012;13:155–158.

- Toseska-Spasova N, Dzipunova B, Tosheska-Trajkovska K, et al. Non-nutritive sucking habit thumb sucking. Journal of Morphological Sciences. 2019;2(1):18–23.

- Passanezi E, Sant’Ana ACP. Role of occlusion in periodontal disease. Periodontol 2000. 2019;79:129–150.

- Gomes GB, Vieira-Andrade RG, Vieira de Sousa R, et al. Association between oronasopharyngeal abnormalities and malocclusion in northeastern Brazilian preschoolers. Dental Press J Orthod. 2016;21:39-45.

- Berwig LC, Montenegro MM, Ritzel RA, Toniolo da Silva AM, Rodrigues Correa EC, Mezzomo CL. Influence of the respiratory mode and nonnutritive sucking habits in the palate dimensions. Brazilian Journal of Oral Sciences. 2011;10(1):42–49.

- Wijey R. It’s time to talk about myofunctional therapy. Available at: https://myoresearch.com/storage/app/media/time-to-talk-about-myofunctional-therapy-0318.pdf. Accessed January 19, 2023.

- Saccomanno S, Berrettin-Felix G, Coceani Paskay L, Manenti R, Quinzi V. Myofunctional Therapy Part 4: Prevention and treatment of dentofacial and oronasal disorders. European Journal of Paediatric Dentistry. 2021;22(4):332–334.

- Merkel-Walsh R. Orofacial myofunctional therapy with children ages 0-4 and individuals with special needs. Available at: ijom.iaom.com/journal/vol46/iss1/䁱/. Accessed January 19, 2022.

- Achmad H, Mutmainnah N, Ramadhany YF. A systematic review of oral myofunctional therapy, methods and development of class ii skeletal malocclusion treatment in children. Sys Rev Pharm. 2020;11:511–521.

- Washington SC, Ray J. Orofacial myofunctional assessments in adults with malocclusion: a scoping review. Int J Orofacial Myology. 2021;47(1):22-31.

- Benkert KK. The effectiveness of orofacial myofunctional therapy in improving dental occlusion. Int J Orofacial Myology. 1997;23:35–46.

- Van Dyck C, Dekeyser A, Vantricht E, et al. The effect of orofacial myofunctional treatment in children with anterior open bite and tongue dysfunction: a pilot study. Eur J Orthod. 2016;38:227–234.

- Shah SS, Nankar MY, Bendgude VD, et al. Orofacial myofunctional therapy in tongue thrust habit: a narrative review. Int J Clin Pediatr Dent. 2021;14:298–303.

- Tanny L, Huang B, Naung NY, Currie G. Non-orthodontic intervention and non-nutritive sucking behaviours: a literature review. Kaohsiung J Med Sci. 2018;34:215–222.

- Jónsson T. Orofacial dysfunction, open bite, and myofunctional therapy. Eur J Orthod. 2016;38:235–236.

From Dimensions of Dental Hygiene. February 2023; 21(2)34-37.