ARTUR PLAWGO / ISTOCK / GETTY IMAGES PLUS

ARTUR PLAWGO / ISTOCK / GETTY IMAGES PLUS

Everything You Need to Know About the Hepatitis C Virus

Identifying patients at high risk for contracting the virus and making referrals for testing and treatment are key to reducing the impact of this serious infection.

This course was published in the February 2023 issue and expires February 2026. The author has no commercial conflicts of interest to disclose. This 2 credit hour self-study activity is electronically mediated.

AGD Subject Code: 148

EDUCATIONAL OBJECTIVES

After reading this course, the participant should be able to:

- Discuss the features and types of the hepatitis C virus (HCV).

- Identify the routes of transmission and incubation for HCV.

- Explain the impact of the opioid crisis on the prevalence of HCV.

- Note the role of oral health professionals in reducing the spread of HCV.

The Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) Bloodborne Pathogens Standard 29 CFR 1910.1030 requires education and training related to bloodborne diseases at the time of hire, annually (at a minimum), and if duties change that involve exposure to blood or other potentially infectious bodily materials.1 Employers must comply with this federal regulation or face potential discipline or fines.

Oral health professionals may be exposed to bloodborne pathogens, including hepatitis C (HCV). As the number of new acute HCV infections has doubled since 2013, clinicians must be up-to-date on how best to protect themselves and their patients.2

Hepatitis Defined

Hepatitis is an inflammation of the liver, a vital organ that filters toxins, creates bile for digestion, aids in blood clotting, metabolizes nutrients, and stores glycogen. When the liver is inflamed or damaged, its function can be affected and may lead to liver cancer or failure.

Hepatitis may be caused by many factors such as heavy alcohol use, exposure to toxins and some medications, and certain medical conditions. However, hepatitis is most often caused by a virus.

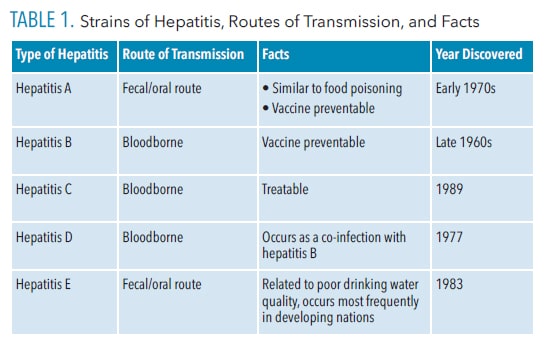

In the United States, the most common types of viral hepatitis are A, B,and C.3 Table 1 outlines the various strains of hepatitis and their source.

Features and Types

HCV is often under reported, but is the most common bloodborne infection in the US.4–6 An enveloped single-strand RNA virus, HCV is less virulent than other strains due to its fatty lipid membrane, which replicates in liver cells.7

Spontaneous clearance of the HCV occurs in approximately half of those who are infected, while the other half becomes chronically infected. In chronically infected individuals, the immune system tries to respond, but during viral replication, the virus transforms, enabling it to elude the body’s defenses.6,7

Chronic HCV results in ongoing inflammation of the liver that progresses slowly, resulting in damage such as thickening, scarring, cirrhosis, and possible carcinoma (liver cancer).6,7 Many of these negative health effects will not present until several years or decades later.8 The US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) reports that approximately five to 25 out of 100 individuals with HCV will develop cirrhosis over a 20-year period with a 1% to 4% risk of liver cancer.6

Seven HCV genotypes have been identified: 1a, 1b, 2, 3, 4, 5, and 6; the first four are the most common in the US.6 Genotype 1a or 1b occurs in approximately 75% of people with HCV in the US. Genotype 2 and 3 impact 10% to 20% of people with HCV in the US.9

Many of the current medications used to treat HCV are effective for nearly all genotypes, whereas previous medications were only effective for genotypes 1 and 4.10 Identifying the genotype is key in properly treating individuals with HCV.

Transmission and Incubation

Transmission of HCV occurs through exposure to blood contaminated with the virus, generally through multiple percutaneous exposures. It is most frequently associated with sharing of needles and syringes among current and former intravenous (IV) drug users.6

To a lesser extent, transmission may also occur via sexual contact; childbirth; sharing of personal items, such as razors and toothbrushes; unregulated tattooing; and occupational exposures such as sharps injuries.6

Groups at highest risk for contracting HCV are former and current IV drug users, those on long term dialysis, recipients of blood transfusions and organ transplants prior to 1992, healthcare workers, infants born to infected mothers, and those with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV).6

The incubation period for HCV infection generally ranges from 45 days to 180 days with a 45-day average. Many patients with HCV have few or no symptoms during the incubation period. Onset of signs for those who are symptomatic generally occur within 2 weeks to 12 weeks. Symptoms are generally mild, non-specific, and flu-like including fever, fatigue, nausea, abdominal pain, loss of appetite, joint pain, dark urine, gray colored stool, and jaundice.6

Early detection is challenging due to the asymptomatic chronic nature of HCV, which can be as long as 20 years or more. Asymptomatic patients are at greater risk for cirrhosis and liver cancer due to delayed diagnosis.6 It is vital for patients to be screened and tested early.

Prevalence and Incidence

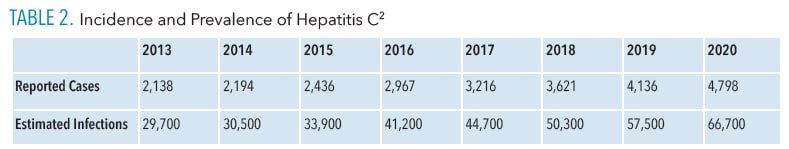

In 2020, 4,798 new cases of acute HCV were reported with an estimated number of 66,700 acute cases nationwide.2 Acute HCV cases were higher in men ages 20 to 39, American Native populations, and those in the East and Southeastern regions of the US.2

Approximately 66% of new HCV cases report a history of IV drug use.2,5 Table 2 provides incidence and prevalence data in the US from 2013 to 2020.

During the 1990s and early 2000s, new acute cases of HCV were declining. Unfortunately, significant and rapid increases ocurred beginning in 2010. At the same time, the number of individuals addicted to opioids drastically grew correlating with a rise in IV drug use.

Impact of the Opioid Crisis

The opioid crisis was caused by widespread abuse of prescription pain medications including oxycodone, which entered the market in 1996. Initial misuse of oxycodone included overdose through oral routes (pills), smoking (inhalation), and crushing the pills. In 2010, oxycodone was reformulated into an “abuse deterrent” version, making it more difficult to crush or dissolve. This led drug users to switch to heroin, a cheaper and easier drug to obtain.8

At the same time, HCV began rapidly increasing. Powell et al8 found a link between the introduction of the reformulated oxycodone and the rise in HCV cases in the US. The biggest increases occurred in rural areas within central Appalachian states, particularly Kentucky, Tennessee, Virginia, and West Virginia.5

Zibbell et al5 reported that acute HCV infections occurred most frequently in non-Hispanic white men (< 30 years) from nonurban areas with a history of IV drug use (73%). The rise in HCV cases in young white men from nonurban areas coincides with the Appalachian region’s prescription opioid abuse problem.

The dramatic increase of HCV cases along with the opioid crisis has affected several subpopulations including pregnant women and adolescents. HCV infections more than doubled among pregnant women between 2009 and 2019 with 138,343 cases in the US.11 Patrick et al11 found a significant increase in US HCV cases (from 1.8% to 5.1%) among pregnant white and Indigenous American women with lower education and socioeconomic status in rural areas.

HCV cases are also increasing among adolescents. Little research has evaluated the problem of HCV in adolescents except for high-risk populations such as those experiencing homelessness and drug addiction.12 The majority (97%) of adolescent cases of HCV include a history of early substance abuse (before age 20) with opioids, cocaine, and crack use.12 The adolescent population is challenging to treat due to stigma, transient nature of care, lack of compliance in seeing a pediatric infectious disease provider, treatment refusal, inadequate follow up, and social deterrents.

HCV epidemics are categorized into three patterns: infections related to high risk behaviors, ongoing infections, and historic infections related to the past.13 The US needs to focus on identifying and testing individuals in order to provide early treatment. Universal testing and testing for at-risk individuals is a primary approach to eradicating HCV.

Testing Recommendations

Current CDC guidance recommends universal one-time HCV testing for all US adults and pregnant women (during each pregnancy), except where prevalence is less than 0.1%.14

Treatment

Although there is no vaccine for HCV, it is treatable. The second generation of direct-acting antiviral agents (DAAs) include a well-tolerated short course (8 weeks to 12 weeks) of oral medications with very few side effects.13 The latest generation of DAA medications are easy to administer (pill or tablet form) and treat a wide variety of genotypes. The previous generation of DAAs were generally only effective against genotypes 1a, 1b, and 4.9

A patient is considered “cured” from HCV once sustained virological response is achieved, as demonstrated in undetectable levels in the blood 12 weeks to 24 weeks after treatment ceases. New treatments for HCV are beginning to impact morbidity and mortality rates as cured people cannot transmit the infection.7 Unfortunately, once cured, patients can once again acquire HCV.6 The development of an HCV vaccine is critical in solving the HCV epidemic.13

Implications for Oral Health Professionals

Oral health professionals must utilize standard precautions for safety in the workplace to reduce the risk of bloodborne disease transmission such as HCV. OSHA and the 2003 CDC guidelines continue to provide comprehensive guidance regarding standard precautions including proper hand hygiene, personal protective equipment, safe work behaviors and safety devices, sharps safety, safe injection practices, disinfection and sterilization of patient care items, environmental infection prevention and control, respiratory hygiene, vaccination for HAV and HBV, and treating all patients as infectious.1,15,16

Fortunately, HCV is inefficiently transmitted by occupational exposure with less than 0.2% seroconversion.17 A literature review stated “dental care does not pose a risk for HCV transmission.”18

The CDC has developed a testing algorithm for oral health professionals with an occupational exposure to HCV.17 Baseline testing of the source patient and oral health professional should be conducted within 48 hours. Two options are available for testing the source patient: a nucleic acid test (NAT) for HCV RNA, or an antibody test (anti-HCV).

The NAT is preferred if the source has engaged in risky behavior, such as IV drug use, in the past 4 months. Once the status of the source patient and oral health professional is known, the oral health professional should be tested with a NAT at 3 weeks to 6 weeks post-exposure. If this test is negative, then a final anti-HCV test should be conducted at 4 months to 6 months post-exposure.

If the oral health professional is positive at 4 months to 6 months, he or she should be referred for treatment with oral DAAs. Immediate post-exposure prophylaxis for HCV is not recommended.17

Conclusion

HCV is a silent disease that can go undetected for many years, resulting in significant liver damage. Universal one-time testing for HCV should be conducted on all US adults, pregnant women, and those with increased risk factors. Identification is now easily accessible to patients with a rapid test. Continued advancements in oral DAAs offer cures with shorter treatment durations.

Oral health professionals must be knowledgeable about HCV in the delivery of safe care. This includes identifying patients at high risk for HCV and making referrals for testing and treatment.

References

- Occupational Safety and Health Administration. Bloodborne Pathogens Standard. Available at: osha.gov/lawsregs/regulations/standardnumber/1910/1910.1030. Accessed January 13, 2023.

- United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Hepatitis C Surveillance. Available at: cdc.gov/hepatitis/statistics/2020surveillance/hepatitis-c.htm. Accessed January 13, 2023.

- United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Viral Hepatitis—Hepatitis C. Available at: cdc.gov/hepatitis/hcv/index.htm. Accessed January 13, 2023.

- Hofmeister MG, Rosenthal EM, Barker LK, et al. Estimating prevalence of hepatitis C virus infection in the United States, 2013-2016. Hepatology. 2019;69:1020–1031.

- Zibbell JE, Iqbal K, Patel RC, Suryaprasad, A, et al. Increases in hepatitis C virus infection related to injection drug use among persons aged <30 years-Kentucky, Tennessee, Virginia, and West Virginia, 2006-2012. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2015;64:453–458.

- United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Hepatitis C Questions and Answers for Health Professionals. Available at: cdc.gov/hepatitis/hcv/hcvfaq.htm#section1. Accessed January 13, 2023.

- Martinez MA, Franco S. Therapy implications of hepatitis C virus genetic diversity. Viruses. 2021;13:1–17.

- Powell D, Alpert A, Pacula RL. A transitioning epidemic: how the rise of the opioid crisis is driving the rise in hepatitis C. Health Affairs. 2019;38:287–294.

- American Liver Foundation. Treating Hepatitis C. Available at: liverfoundation.org/liver-diseases/viral-hepatitis/hepatitis-c/treating-hepatitis-c/. Accessed January 13, 2023.

- Anderson LA. What are the new drugs for the treatment of hepatitis C? Available at: drugs.com/medical-answers/new-drugs-hepatitis-3511306/. Accessed January 13, 2023.

- Patrick SW, Dupont WD. McNeer E, et al. Association of individual and community factors with hepatitis C infections among pregnant people and newborns. JAMA Health Forum. 2021;2:1–18.

- Mari PC, Gulati R, Fragassi P. Adolescent hepatitis C: prevalence, impact, and management challenges. Adolesc Health Med Ther. 2021;12:45–53.

- Lombardi A, Mondelli MU, ESCMID Study Group for Viral Hepatitis (ESGVH). Hepatitis C: Is eradication possible? Liver Int. 2018;39:416–426.

- Schille S, Wester C, Osborne M. Wesolowski L, Ryerson B. CDC recommendations for hepatitis C screening among adults-United States, 2020 recommendations and reports. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2020;69:1–17.

- Kohn WG, Collins AS, Cleveland JL, et al. Guidelines for infection control in dental healthcare settings 2003. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2003;52(RR-17):1–66.

- United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Summary of Infection Prevention Practices in Dental Settings. Available at: cdc.gov/oralhealth/infectioncontrol/pdf/safe-care2.pdf. Accessed January 13, 2023.

- Moorman AC, de Perio MA, Goldschmidt R, et al. Testing and clinical management of health care personnel potentially exposed to Hepatitis C Virus—CDC Guidance, United States, 2020. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2020;69:1–8.

- Averbukh LD, Wu GY. Highlights for dental care as a Hepatitis C risk factor: a review of literature. J Clin Transl Hepatol. 2019;7:346–351.

From Dimensions of Dental Hygiene. February 2023; 21(2)38-41.