Third Molar Removal

While the decision to remove third molars without the presence of pathology has become controversial, this case study illustrates the risks of leaving them intact.

Dental hygienists must be proficient in the clinical and radiographic evaluation of third molars, most of which are extracted. However, some patients present with special circumstances surrounding their third molars, such as jaw structures that cannot support wisdom teeth or a high risk for developing caries on neighboring teeth. For this reason, third molar prophylactic extraction has been on the increase in many dental offices. Many young, healthy people are having their impacted wisdom teeth removed when there is no sign of pain or irritation.1 Whether removing impacted teeth is necessary is a controversial subject. Those who oppose automatically extracting the four teeth when there is no reason to do so say “watchful waiting” is a better path.2 There is no evidence of widespread third-molar infection and pathology or of medical necessity to justify surgery.1 On the other hand, a 2011 white paper from the American Association of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgeons states impacted third molars should be removed—even if they are asymptomatic—when there is a risk for pathology.3

In most cases, the four third molars at the back of the jaw will start to erupt between the ages of 17 and 25.2 Extraction is often performed in preparation for orthodontic treatment or orthognathic surgery, or to prevent complications that may arise in the future.4 Therapeutic reasons for extracting impacted third molars include: periodontal problems, presence of cysts, acute or chronic pericoronitis, destruction of adjacent periodontal tissues, and the presence of carious lesions.4,5Complications that may arise due to extracting third molars are pain, swelling, secondary infection, hemorrhage, alveolar osteitis, paresthesia of the inferior alveolar nerve, and impaired healing in older patients.1,3–5

A study revealed impacted third molars in patients older than 50 were likely to develop cysts or tumors, especially in men.5 Most oral health professionals agree that third molars should be extracted in the presence of recurrent gingival infection or pericoronitis, irreparable tooth decay, abscess, cysts, tumors, damage to nearby teeth and bone, or pathological conditions.6

The following case study presents a patient for whom an impacted third molar was detrimental to his health and well-being.

Case Study

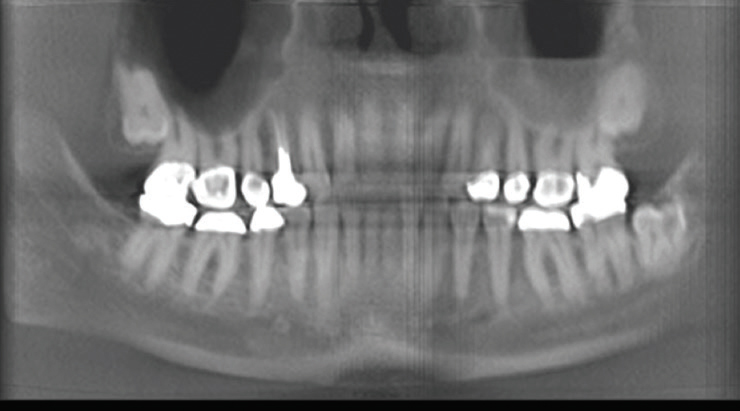

On August 25, 2016, a 62-year-old man, referred to as “Mr. Smith,” noticed a sore left jaw, limitation of opening, and difficulty swallowing. No tooth discomfort was present at the time, but he did have some difficulty eating. He had a sore throat and had been taking cough drops (2 years prior he had experienced an allergic reaction to the same cough drops) for 10 days. On August 26, Mr. Smith experienced swelling on the left side of his face and was unable to eat. On August 27, his lymph nodes were swollen under his mandibular left jaw, so he took himself to the nearest urgent care center. He disclosed his past allergy to cough drops and the physician administered a steroid injection to decrease swelling in Mr. Smith’s mandibular left jaw. The swelling improved short-term, but on August 28, there was severe swelling on the mandibular left jaw and even more decreased opening, or trismus. His temperature was 101° in the afternoon. Later that evening, Mr. Smith was in excruciating pain and was unable to swallow, so he went to the local emergency department (ED). The ED staff took cone-beam computed tomography (CBCT) images (Figure 1) and informed Mr. Smith of a possible infected pocket in his left tonsil area. As he was having difficulty swallowing, he was admitted to the hospital and placed on intravenous pain medications and antibiotics. Figure 1 shows the ill-defined hypodense collection that is seen within the left posterior oropharynx extending inferiorly along the left hypopharynx with possible posterior extension to the retropharyngeal space. Figure 2 shows the thickness on the left side of the ramus.

On August 29, the swelling was controlled with the use of steroids and antibiotics, and Mr. Smith was given a blood thinner to prevent clot formation. He was still not able to eat or drink, but his temperature had improved to 99°. An ear, nose and throat (ENT) physician suggested it may be a dental issue. The initial swelling was noted on the left retropharyngeal area and left masseteric and submandibular area. Mr. Smith had a white blood cell count of 20,000 at this time.

On August 30, the swelling in the affected area was reduced and Mr. Smith was able to eat and drink broth and juice. His temperature was normal. The ENT physician called in an oral surgeon who did not suspect a tooth concern after evaluating the X-rays at the hospital.

On August 31, Mr. Smith was released from the hospital with slight soreness and limitation of opening in the left jaw. The physician instructed the patient on how to perform exercises to increase mobility in his jaw. Mr. Smith visited the oral surgeon the same day and his medical history was as follows: blood pressure 128/83; pulse 59; weight 227 lbs; past medical history: hypertension, asthma, sinus trouble, arthritis, tumor/cancer; medications: lisinopril, glucosamine, multivitamin, ibuprofen; no allergies; and no smoking or alcohol use. The oral surgeon captured a panoramic radiograph that revealed decay and infection around tooth #17, which was a bony impaction. The oral surgeon scheduled an appointment for extraction of tooth #17 and suggested that Mr. Smith continue with the pain medication and antibiotics until his extraction scheduled for mid-September.

On September 1, Mr. Smith decided to continue with exercises to assist in movement of his jaw and he was able to eat some rice. But, after some improvement, the patient had a relapse on September 2. There was moderate swelling on the mandibular left jaw from the mid-ear region to the submandibular and mental region of the chin. The oral surgeon scheduled an emergency extraction of tooth #17 and was able to remove approximately half of the tooth due to swelling and trismus. Between 5 cc and 10 cc of exudate was removed from the surgical site, and the patient was given oxycodone and acetaminophen. Mr. Smith’s antibiotic regimen was switched to augmentin 875 mg twice per day and he was advised to apply ice packs on the left side of his jaw. His swallowing and ability to drink fluids greatly improved.

For the next few days, Mr. Smith continued with pain medications, antibiotics, and ice treatments. He graduated to soft foods and soup soon after surgery. Lymph node swelling improved within a few days and he was able to begin warm salt-water rinses to debride the surgery site. Within a week of surgery, Mr. Smith transitioned to ibuprofen and the pain was much improved.

By the follow-up appointment with the oral surgeon on September 9, the patient was able to gently use a syringe to flush the extraction site with diluted chlorhexidine. A follow-up panoramic radiograph was taken.

Radiographic Assessment

Figure 3 was taken before surgery to remove the third molar, while Figure 4 was captured post-surgery. Figure 3 shows a diffuse radiolucency on the superior and distal aspect of tooth #17; advanced caries on the distal of tooth #17; roots mostly developed with slight thickness at the apical region; possible bony impaction superior to the distal half of tooth #17, leading to potential bone resection during extraction; deep vertical bony defect on the mesial of the impacted #17 very close to the mandibular canal; and inferior alveolar nerve.

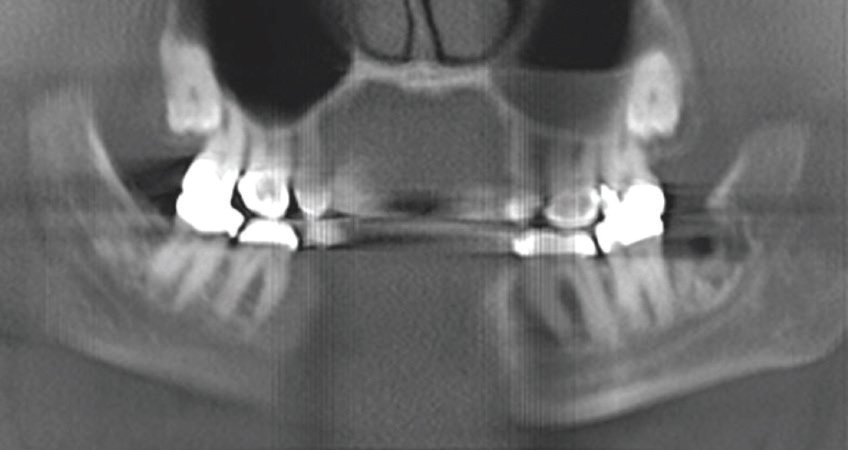

Figure 4 demonstrates that sectioning was performed on tooth #17; however, some of the root (mesial and distal apices) had to remain due to concern about the close proximity of the mandibular canal and inferior alveolar nerve. The lamina dura is still evident in the extraction site area of tooth #17. The mandibular canal and inferior alveolar nerve exhibited no compression or damage during the oral surgery and tooth #18 was not damaged during sectioning of tooth #17.

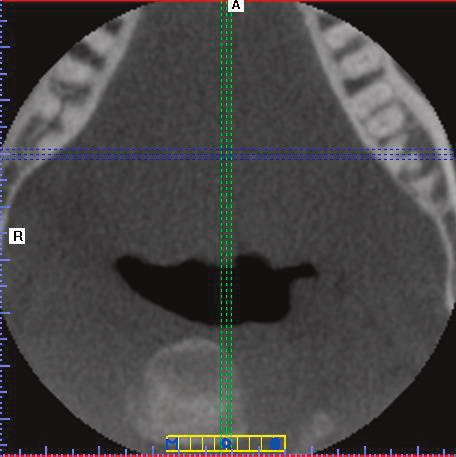

A panoramic image and three-dimension CBCT (axial and coronal) images were taken on September 16. The post-surgery CBCT axial image (Figure 5) shows residual root fragments from tooth #17 (blue dotted line passing through the fragments).

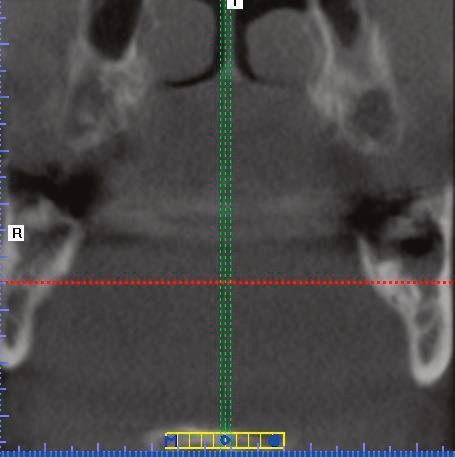

The post-surgery CBCT coronal image (Figure 6) demonstrates residual root fragments from tooth #17 (red dotted line passing through the fragments). Figure 7 shows the residual root of tooth #17 where the oral surgeon had to leave it in the jaw.

Discussion

After reviewing Mr. Smith’s dental history and timeline, some concerns are apparent. First, the patient’s trismus and difficulty swallowing are red flags. These symptoms can progress quickly, especially because the patient has a history of allergic reaction to the cough drops he was using. Second, his elevated temperature may indicate an infection in the head and neck region. In addition, his white blood cell count suggested this possibility. Another concern was the prescription of blood thinners, which could delay a surgical procedure. There was difficulty healing and less bone regeneration potential due to the patient’s age and the amount of infection present in the mandibular left region.

The use of alternate views of radiographs (two-dimension panoramic and three-dimension CBCT) was extremely beneficial in the interpretation and diagnosis of Mr. Smith’s condition. These imaging systems assisted the oral surgeon in the removal of tooth #17 and were instrumental in preventing paresthesia and further destruction to the alveolar bone. The images helped the patient’s healing process and the drainage of infection from the extraction site. In addition, the oral surgeon can monitor the remaining root fragments to ensure no further infection or cysts/abscesses appear.

Conclusion

Each patient has different risk factors that can occur before, during, and after surgery. The older the patient, the more time needed for proper post-operative recovery. Third molar removal surgery is specific to each individual and the procedure is not to be entered into lightly. Each patient can present with a variety of risks and implications to consider when treatment planning for removal of third molars. The use of quality radiographs and supplemental extraoral projections (such as CBCT) will aid in the quality of the diagnosis and long-term patient success. However, it will be paramount to monitor and maintain Mr. Smith’s bone health and regeneration, residual root fragments, and surgery site in the area of tooth #17.

REFERENCES

- Friedman JW. The prophylactic extraction of third molars: a public health hazard. Am J Public Health. 2007:97:1554–1559.

- Oberliesen E. Dentists debate need to extract wisdom teeth. Los Angeles Times. January 2, 2015.

- Singh YK, Adamo AK, Parikh N, Buchbinder D. Transcervical removal of an impacted third molar: an uncommon indication. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2014;72:470–473.

- Blondeau F, Daniel N. Extraction of impacted mandibular third molars: postoperative complications and their risk factors. J Can Dent Assoc. 2007;73:325.

- Shin SM, Choi EJ, Moon SY. Prevalence of pathologies related to impacted mandibular third molars. Springerplus. 2016;5:915.

- Macdonald, F. Evidence is mounting that routine wisdom teeth removal is a waste of time. 2016. Available at: sciencealert.com/no-you-probably-don-t-needto-get-your-wisdom-teeth-removed-ever. Accessed November 16, 2017.

Featured photo by LEAF/ISTOCK/GETTY IMAGES PLUS

From Dimensions of Dental Hygiene. December 2017;15(12):27-29.