The Key to Safety

Effective infection control procedures ensure a safe work environment for both patients and practitioners.

Infection control in the clinical dental setting is key to the safe provision of oral healthcare for both patients and practitioners. Dental hygiene treatment generally results in a significant amount of bleeding and aerosols, and this places dental hygienists at risk of bloodborne infection and exposure to pathogens. As more patients seek care in the dental office setting and new pathogens are discovered, practitioners must be resolute in following strict infection control standards. In order to protect their colleagues, patients and themselves, clinicians should adhere to protocol as specified by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and other regulatory agencies.1

CDC REGULATIONS

The CDC introduced the use of Universal Precautions in 1987.2 The guidelines focus mainly on reducing the risk of bloodborne pathogens and state that all blood and serum body fluids must be treated as infectious because often patients who have bloodborne infections do not exhibit symptoms and may be unaware of the infection.3 In other words, the blood of all patients is potentially infectious and should be treated as such.

In 1996 the CDC modified its Universal Precautions to maximize the prevention of different modes of transmission of pathogenic microorganisms. The new system adopted a two-level approach consisting of Standard Precautions and Transmission-based Precautions. These guidelines address the prevention of infection from not only blood and other bodily fluids, but also discuss contact isolation, droplet isolation, and airborne isolation. The standards were updated in 2007.4

Standard Precautions apply to all patients, regardless of whether their infection status is either confirmed or suspected.5 These further the tenets of Universal Precautions in an effort to maximize protection of patients and practitioners. Hand washing, personal protective equipment, injury prevention, the management of patient-care items, and environmental surface protectants are all Standard Precautions. In the dental setting, standard and universal precautions are the same because saliva is considered an effective mode of infectious transmission.5

Transmission-based Precautions are used in addition to Standard Precautions when treating patients who have a confirmed or strongly suspected infectious disease, such as influenza, varicella, herpes simplex 1 or 2, or tuberculosis. Transmission-based Precautions consist of three additional categories: airborne isolation, droplet isolation, and contact isolation.1,4,6 These precautions require extensive proactive measures, thus, many dental offices may not have the resources available to provide this level of protection. For example, a patient with active airborne infection needs to be placed in an airborne infection isolation room with special ventilation in a hospital-dental setting.1,6,7 If possible, the provision of dental care should wait until a patient with an infectious disease, such as chicken pox, influenza or tuberculosis, is no longer contagious.6

When instituting or updating an infection control plan, practitioners should carefully follow the CDC’s Guidelines for Infection Control in Dental Healthcare Settings 2003. These guidelines include detailed instructions for effective infection control specifically in dental offices.6

REDUCING THE RISK OF CONTAMINATION

Patients should be issued eye protection at the beginning of the dental appointment. They also should rinse with an antimicrobial mouthwash before any dental treatment is provided in order to minimize the amount of microorganisms in droplets, splatter and aerosols.7

Standard Precautions require that practitioners use scrubs, closed-toe shoes, water resistant and antimicrobial lab coats, face masks, face shields, and latex gloves. Scrubs and lab coats should be changed daily and never washed at home. Washing contaminated clinical clothes at home puts household members at risk of possible innoculation with contagious pathogens. Lab coats and scrubs should be washed by a professional laundry service with a specialty in clinical clothing. Disposable lab coats are indicated when treating patients with confirmed infectious diseases.

Protective eyewear is also essential for practitioners. Goggles alone may not fully protect the face of a practitioner, so face shields should be worn to provide barrier protection for the entire face. Patient protective eyewear and practitioner protective eye wear, such a goggles, faceshields, or loupes, can be cleaned with a disinfectant.8

Hand hygiene, which includes hand washing, hand antisepsis, and surgical hand antisepsis is the most essential component of reducing the risk of transmitting infectious organisms.3 Hand washing for two minutes with antimicrobial soap at the beginning and at the end of each practice day is indicated, as well as hand washing for 15 seconds (two cycles of lather and rinse) between each patient.9 Using alcohol-based hand rubs (hand sanitizers) is also effective on hands that are not visibly soiled.6 When selecting an alcohol-based hand sanitizer, the product should also include an antiseptic such as chlorhexidine, quaternary ammonium compounds, octenidine or triclosan in order to ensure efficacy.10

Hair should be short or put up and away from the face to prevent debris and aerosols from getting into the hair. The most effective means of protection is achieved by wearing a hair bonnet.

Hair should be short or put up and away from the face to prevent debris and aerosols from getting into the hair. The most effective means of protection is achieved by wearing a hair bonnet.

Artificial nails can harbor gram-negative organisms and thus should not be worn by dental practitioners.11-14 Chipped nail polish (though not newly applied nail polish) can also collect bacteria.15,16 Nails need to be kept short to prevent microorganisms from collecting under the nails, to protect patients from scratches, and to prevent tears in exam gloves.6 Jewelry should not be worn because microorganisms can become trapped in rings or earrings.17

Gloves should be used for one patient only and then thrown away. The use of gloves also does not reduce the need for hand washing.6 If the patient or a clinician has a latex allergy, vinyl or nonlatex gloves are indicated; however, nonlatex gloves are more porous than latex. They are acceptable for routine examination, but nonlatex gloves are not the first choice when treating patients with bloodborne infections.4,6,9 Therefore it is important to double glove when using nonlatex gloves to prevent body fluids and microorganisms from seeping through.

DISINFECTION AND BARRIERS

All the equipment and surfaces in the treatment room need to be cleaned and disinfected thoroughly or covered effectively. Infection control tape or barrier tape must be placed on all surfaces that could be touched with saliva-contaminated or blood-contaminated gloves, and the tape must be changed after each patient.

A study by McColl et al used the Kastle-Meyer forensic test for blood to determine the route of cross-contamination between patients, dental practitioners and equipment.18 The results showed that untaped air/water syringe buttons were still contaminated with 40% of microorganisms after the first wipe with a surface disinfectant. On the second wipe, 10% of micro organisms still remained. Bib chains were also found to be contaminated with 22% of microorganisms after the first wipe.18 To prevent this type of cross-contamination, if the air-water syringe cannot be autoclaved, it must be covered with plastic tubing or infection control tape. Bib chains and air/water syringe tips should be sterilized after each patient. The introduction of bibs with self-adhesive pads and disposable bib holders, which are discarded after each patient use, are also effective options.

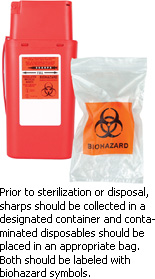

All sharps should be collected in a designated red plastic container labeled with biohazard symbols, and all disposable materials contaminated with body fluids should be placed in an appropriate plastic bag also labeled with biohazard symbols.

STERILIZATION

Practitioners must handle instruments carefully to avoid puncture wounds. All dental instruments should be cleaned in an ultrasonic washer as opposed to hand scrubbing.19 The hand scrubbing of instruments presents the risk of injury. Ultrasonic washers work with cassettes and high temperature solution. Autoclave sterilization for 45 minutes at 121° C (250° F) degrees and 15 psi pressure should be standard procedure.9 As an extra precaution, instruments contaminated with infectious pathogens should be cleaned separately and then placed into the autoclave. Biological test spore indicators need to be used every week to confirm if sterilization has occurred.

Handpieces must be sterilized after each patient. Instruments and handpieces should be sterilized in sterilization pouches or stainless steel cassettes with a sterilization tape that changes color when sterilization is complete. Evacuation of suction lines and water lines must be accomplished by flushing them out with water for at least three minutes in the beginning of the day to ensure the elimination of bacteria that may have colonized overnight, and for at least 30 seconds after each patient. Highand low-speed suctions must be irrigated with an evacuation system cleaner and water at the end of each day to clear the lines of debris and microorganisms.20

RISK OF AEROSOLS

Patients affected with bloodborne pathogens, such as HIV, hepatitis B, C, D, and E, and carriers of viral hepatitis, should be treated with Transmission-based Precautions. Patients with infectious diseases should also be scheduled for the last appointments of the day when any type of invasive treatment needs to be rendered. Practitioners must thoroughly disinfect equipment and vent the operatory to eliminate microorganisms and minimize aerosols.

Due to the risk of aerosols, the use of an ultrasonic scaler is contraindicated with patients who have highly virulent bloodborne diseases. By way of clarification, aerosols are particles of blood, saliva and microorganisms smaller than 3 µm to 5 µm in diameter that can be suspended in the air up to seven days and are generated by ultrasonic scalers and air polishers.7

The use of an antiseptic mouth wash prior to treatment will decrease the micro-bial number of aerosols generated during the use of an ultrasonic scaler, high-speed handpiece or air polishing. High volume evacuation will significantly reduce aerosols.7

Dental aerosols eventually settle onto surface areas, including countertops and dental equipment, emphasizing the importance of addressing all the equipment in the dental operatory, including patient charts and computer keyboards. All countertops and equipment in a dental operatory should be wiped every day with a surface disinfectant to eliminate microorganisms. Administrative tools such as pens, patient charts, computer mice and keyboards must not be handled with contaminated gloves. During periodontal or hard tissue charting, a colleague should assist with the data entry or a voice-activated device should be used. Disposable keyboard covers should be used or a practice may choose specially designed keyboards that have a flat surface to allow for effective covering and disinfection. All administrative tools should be wiped with a disinfectant daily. All pens and pencils in the treatment room can be color coded so they are not brought to the front desk area from the treatment room. Digital patient records eliminate paper charts that can be accidentally contaminated.

Proper infection control is the key to providing and receiving dental care safely. Following the CDC’s guidelines and implementing the recommended tools for minimizing occupational exposure to bloodbone and airborne pathogens will help keep dental practioners and patients healthy.

GLOSSARY OF TERMS6

Alcohol-based hand rub: An alcohol-containing preparation designed for reducing the number of viable microorganisms on the hands.

Antimicrobial soap: A detergent containing an antiseptic agent.

Disinfectant: A chemical agent used on inanimate objects (e.g., floors, walls or sinks) to destroy virtually all recognized pathogenic microorganisms, but not necessarily all microbial forms (e.g., bacterial endospores). The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) groups disinfectants on the basis of whether the product label claims limited, general or hospital disinfectant capabilities.

Disinfection: Destruction of pathogenic and other kinds of microorganisms by physical or chemical means. Disinfection is less lethal than sterilization, because it destroys the majority of recognized pathogenic microorganisms, but not necessarily all microbial forms (e.g., bacterial spores). Disinfection does not ensure the degree of safety associated with sterilization processes.

Droplets: Small particles of moisture (e.g., spatter) generated when a person coughs or sneezes, or when water is converted to a fine mist by an aerator or shower head. These particles, intermediate in size between drops and droplet nuclei, can contain infectious microorganisms and tend to quickly settle from the air such that risk of disease transmission is usually limited to persons in close proximity to the droplet source.

Hand hygiene: General term that applies to hand washing, antiseptic handwash, antiseptic hand rub, or surgical hand antisepsis.

Sterile: Free from all living microorganisms; usually described as a probability (e.g., the probability of a surviving microorganism being one in 1 million).

Sterilization: Use of a physical or chemical procedure to destroy all microorganisms including substantial numbers of resistant bacterial spores.

Ultrasonic cleaner: Device that removes debris by a process called cavitation, in which waves of acoustic energy are propagated in aqueous solutions to disrupt the bonds that hold particulate matter to surfaces.

REFERENCES

- Harte JA. Standard and transmission-based precautions: an update for dentistry. J Am Dent Assoc . 2010;141:572-581

- Universal Precautions for Prevention of Transmission of HIV and Other Bloodborne Infections. Available at: www.cdc.gov/ncidod/dhqp/bp_universal_precautions.html. Accessed May 27, 2010.

- Eklund KJ. Preventing disease and promoting health. Dimensions of Dental Hygiene . 2004;2:26-30.

- Siegel JD, Rhinehart E, Jackson M, Chiarello L; Health Care Infection Control Practices Advisory Committee. 2007 Guideline for Isolation Precautions: Preventing Transmission of Infectious Agents in Health Care Settings. Am J Infect Control . 2007;35(10 Suppl 2): S65-164.

- Eklund KJ, Bednarsh H. Maintaining personnel health in the dental office. Dimensions of Dental Hygiene . 2009;7(1):18-20.

- Kohn WG, Collins AS , Cleveland JL, Harte JA, Eklund KJ, Malvitz DM, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Guidelines for infection control in dental health-care settings—2003. MMWR Recomm Rep . 2003;19;52(RR-17):1-61.

- Harrel SK, Molinari J. Aerosols and splatter in dentistry: a brief review of the literature and infection control implications. J Am Dent Assoc . 2004;135:429-437.

- Salsberg K. Maintenance of Dental Magnification Loops. Available at: www.oralhealthjournal.com/issues/story.aspx?aid=1000224834. Accessed May 27, 2010.

- Lux J. Infection control practice guidelines in dental hygiene—part 1. Canadian Journal of Dental Hygiene. 2008;42(2):63-114.

- Rotter M. Hand washing and hand disinfection. In: Mayhall CG, ed. Hospital epidemiology and Infection Control . 2nd ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 1999:1339-1355.

- Pottinger J, Burns S, Manske C. Bacterial carriage by artificial versus natural nails. Am J Infect Control . 1989;17:340344.

- McNeil SA, Foster CL, Hedderwick SA, Kauffman CA. Effect of hand cleansing with antimicrobial soap or alcohol-based gel on microbial colonization of artificial fingernails worn by health care workers. Clin Infect Dis . 2001;32:367-372.

- Rubin DM. Prosthetic fingernails in the OR: a research study. AORN J . 1988;47:944-945.

- Hedderwick SA, McNeil SA, Lyons MJ, Kauffman CA. Pathogenic organisms associated with artificial fingernails worn by healthcare workers. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol . 2000;21:505-509.

- Baumgardner CA, Maragos CS, Walz J, Larson E. Effects of nail polish on microbial growth of fingernails: dispelling sacred cows. AORN J. 1993;58:84-88.

- Wynd CA, Samstag DE, Lapp AM. Bacterial carriage on the fingernails of OR nurses. AORN J . 1994;60:796,799-805.

- Trick WE, Vernon MO, Hayes RA, et al. Impact of ring wearing on hand contamination and comparison of hand hygiene agents in a hospital. Clin Infect Dis . 2003;36:1383-390.

- McColl E, Bagg J, Winning S. The detection of blood on dental surgery surfaces and equipment following dental hygiene treatment. Br Dent J . 1994;176:65-67.

- Harte JA, Molinari JA. Instrument processing and recirculation. Practical Infection Control in Dentistry . 3rd ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott, Williams & Wilkins; 2010:221-231.

- Crawford L, Yu Z, Keegan E, Yu T. Comparison of Commonly used Surface Disinfectants. Available at: www.infectioncontroltoday.com/articles/0b1feat2.html. Accessed May 27, 2010.

From Dimensions of Dental Hygiene. June 2010; 8(6): 64, 66, 68-70.