The Danger Is Real

While hookah smoking is often seen as a safe alternative to other forms of tobacco use, the research says otherwise.

This course was published in the September 2015 issue and expires September 30, 2018. The author has no commercial conflicts of interest to disclose. This 2 credit hour self-study activity is electronically mediated.

EDUCATIONAL OBJECTIVES

After reading this course, the participant should be able to:

- Define waterpipe, or hookah smoking.

- Identify factors contributing to the popularity of this practice.

- Discuss common misconceptions about hookah smoking.

- Identify systemic and oral health risks associated with this type of tobacco use.

- Explain the role of the dental hygienist in promoting health and raising awareness about these risks.

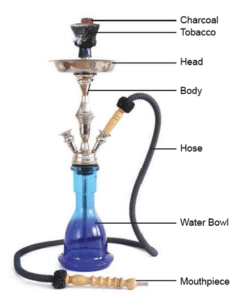

While there may be differences in design, most waterpipes include a mouthpiece, hose, water bowl, body, and head (Figure 1).3–5 The mouthpiece and hose are used for inhalation. The bowl is filled with water, and the head is packed with dampened tobacco (approximately 10 g to 20 g). Perforated foil and a lit fragment of charcoal cover the tobacco. The charcoal is frequently replenished during a smoking session.6 The warm air and charcoal combustion move through the tobacco, producing smoke. The smoke then passes through water and is inhaled by the user.6

HISTORY BECOMES A TREND

Hookah smoking is a 500-year old tradition with roots in the Middle East, Egypt, India, and Turkey.4,7 Its use remains commonplace in Pakistan, India, Bangladesh, parts of China, and Turkey, and is often shared as a social activity among families, including children.8 Approximately 100 million people engage in waterpipe smoking each day.9

The popularity of waterpipe smoking has been increasing in the US, with 10% to 20% of the young adult population participating.7 College students seem to be particularly vulnerable to this form of tobacco use. In 2008, 470 hookah establishments were included in the US waterpipe tobacco smoking cafe and bar directory, many within close proximity to colleges and universities.10 And the number of establishments is growing, with approximately five new hookah bars opening per month.10 Recent research has investigated tobacco trends among college students and found that waterpipe smoking is the second most commonly used tobacco product after cigarettes.11,12 While tobacco use has significantly declined in the US across all populations, Primack et al12 found that 8.4% of surveyed university students were hookah users and 16.8% were cigarette smokers. These numbers demonstrate that tobacco use remains a significant public health risk that must be continually addressed.

THE APPEAL

Waterpipe smoking appeals to users due to a multitude of factors. First, the tobacco that is burned in a hookah is available in a wide variety of flavors such as apple, mint, chocolate, coconut, plum, mango, and strawberry.8 These flavors mask tobacco’s strong taste. Also, when the flavored tobacco is burned, it releases a pleasant and sweet aroma as opposed to the odoriferous smoke emitted by cigarettes. Waterpipe smoking is also a social activity, with users experiencing a sense of community and relaxation.13 Young people may also see hookah smoking as fashionable and trendy.

Tobacco is easily accessible and affordable, and legal starting at age 18 in the US.13

MISCONCEPTIONS

The risks of waterpipe smoking are often downplayed compared to cigarette use, possibly increasing the acceptance of this practice. A primary misconception is that hookah smoking is less harmful and less addictive than conventional cigarettes. Many also believe that waterpipe smoke enters the lungs differently than cigarette smoke, decreasing health risks.14 Some users mistakenly think that the harmful chemicals contained in tobacco are not inhaled because the water filters out toxins from the smoke.15 In fact, nicotine and toxin exposure grow with each puff taken from a waterpipe.16 Another misconception common among adolescents is the idea that waterpipe smoking is healthy because the tobacco contains fruit. Researchers have deemed hookah users with these misconceptions as “tobacco naive.”17

Misconceptions regarding the health risks of hookah smoking are often propagated through marketing. Advertisements for hookah bars frequently fail to offer information regarding adverse health effects, and instead focus on waterpipe smoking’s supposed relaxation benefits.18 The waterpipe tobacco industry is unregulated.19 A recent study analyzing waterpipe smoking advertisements geared toward young adults found that the messages associated sociability and attractiveness with the practice.20 They also depicted waterpipe smoking as a healthier lifestyle choice compared to other tobacco products. To date, there haven’t been any widespread public health campaigns on the hazards of waterpipe smoking. Without such campaigns, individuals may continue to assume waterpipe smoking is a safe option.13

TOXIC EXPOSURE

Waterpipe smoking exposes users to a variety of toxins such as nicotine, polycyclic hydrocarbons, carbon monoxide, and nitrosamines.21 Due to the presence of the highly addictive chemical nicotine, hookah smoking is considered a habit-forming practice. Smokers can potentially absorb higher amounts of toxins from waterpipe smoking, as one puff from a hookah contains 12 times more smoke than a conventional cigarette.22 In an hour-long session, users may inhale approximately 200 puffs when compared to the 20 puffs it takes to finish a conventional cigarette.4 Research has demonstrated that the level of nicotine in a user’s bloodstream can increase up to 250% after one 45-minute waterpipe smoking session.23

The charcoal that burns the tobacco in the waterpipe releases high levels of carbon monoxide and metals.23 Users are exposed to four times more carbon monoxide during a 45-minute waterpipe smoking session compared to smoking a single cigarette.24 Waterpipe tobacco smoke also contains charcoal combustion and ignition products.24

SYSTEMIC AND ORAL HEALTH IMPLICATIONS

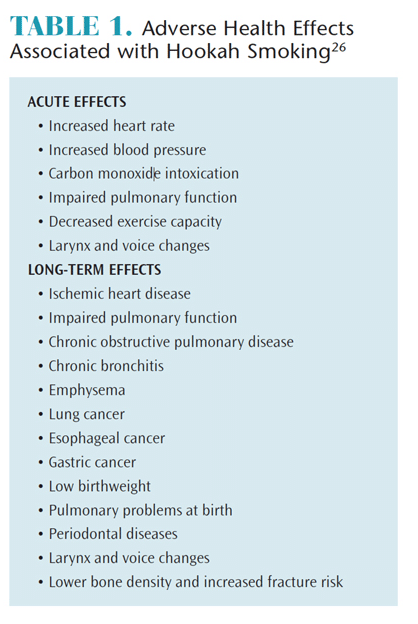

The literature suggests that waterpipe smoking is linked to numerous health conditions, such as pulmonary disease, coronary heart disease, pregnancy complications, cancer, oral diseases, and communicable diseases, therefore classifying it as a public health threat.5,25 Both users and nonusers are at risk for health complications when exposed to hookah smoke. Table 1 provides a list of adverse health effects associated with hookah smoking.26

Reduced pulmonary function is a negative health effect of hookah smoking and may lead to chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.8 The lung function of waterpipe smokers is similar to that of cigarette smokers.19

Exposure to carbon monoxide, nicotine, and other harmful chemicals places waterpipe smokers at an increased risk for developing atherosclerosis and coronary artery disease.27 Hookah smoking also increases blood pressure and heart rate.1 A study that assessed the acute cardiovascular effects of waterpipe smoking by comparing heart rate and blood pressure measurements before and after a 30-minute to 60-minute hookah smoking session found significant increases in heart rate (ranging from 4.1 bpm to 16 bpm) and a rise in systolic and diastolic blood pressure (ranging from 6.7 mmHg to 15.7 mmHg and 2.0 mm Hg to 14 mmHg, respectively).26 Research has also shown that female hookah smokers are at increased risk of delivering low-birthweight babies, as well as infants with respiratory issues.1,8

Carbon monoxide toxicity is an acute health hazard that affects hookah smokers and results in elevated blood carboxyhemoglobin levels.26 Additional symptoms include dizziness, emesis, headache, nausea, syncope, and vertigo.24

Oral health is negatively impacted by waterpipe smoking. Conditions such as staining, alterations in taste, and oral malodor are common among users.1 Hookah smokers are also at greater risk of periodontal diseases, dry sockets, and squamous cell carcinoma than nonusers.1,5 An increase in plaque accumulation, bone loss, and periodontal pocket depth (greater than 5 mm) have been reported.28 The tobacco juices created from waterpipes are known to irritate the oral cavity, placing smokers at increased risk of oral cancer.7

The probability of transmitting infectious diseases is also elevated among waterpipe smokers because the same mouthpiece is shared with fellow users. The hookah itself may also be contaminated with infection-causing bacteria when it is being prepared.8,29 Tuberculosis, herpes simplex, hepatitis C, Epstein-Barr virus, and respiratory viruses are all potential transmissible diseases that can be acquired through waterpipe use.8,29

CONSIDERATIONS FOR ORAL HEALTH PROFESSIONALS

Dental hygienists are leaders in the tobacco cessation arena and their expertise should include the hazards of waterpipe smoking, as well as strategies to curtail its use. Studies have shown a disconnect between the fact-based knowledge of waterpipe smokers and their perceived knowledge.11 When accurate information about the risks of this habit is provided to patients by trusted health care providers, they may be more inclined to quit.11

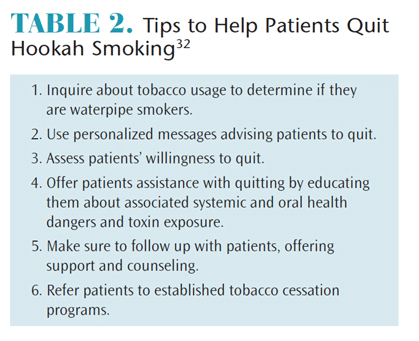

Hookah users can be identified when reviewing medical histories, assuming questions on tobacco use are included.30 Patients who partake in waterpipe smoking should undergo a thorough risk assessment to evaluate oral and systemic health and note any negative effects.23,31 Dental hygienists need to educate these patients about the toxins contained in tobacco and the health risks associated with its use. The misconceptions about the safety of hookah smoking need to be dispelled. Patient education should aim to modify risk factors and motivate patient cooperation. Pointing out the visible changes in patients’ mouths caused by their tobacco use may increase their desire to quit. Tobacco cessation strategies should be provided, as well as follow-up on patients’ progress and referrals to tobacco-cessation programs. Table 2 lists recommendations for helping patients quit hookah smoking.32

Hookah users can be identified when reviewing medical histories, assuming questions on tobacco use are included.30 Patients who partake in waterpipe smoking should undergo a thorough risk assessment to evaluate oral and systemic health and note any negative effects.23,31 Dental hygienists need to educate these patients about the toxins contained in tobacco and the health risks associated with its use. The misconceptions about the safety of hookah smoking need to be dispelled. Patient education should aim to modify risk factors and motivate patient cooperation. Pointing out the visible changes in patients’ mouths caused by their tobacco use may increase their desire to quit. Tobacco cessation strategies should be provided, as well as follow-up on patients’ progress and referrals to tobacco-cessation programs. Table 2 lists recommendations for helping patients quit hookah smoking.32

Currently, US federal law does not require warning labels for pipe tobacco, which is used in waterpipe smoking.18,33 This means it is up to health care providers to educate patients about the risk of all types of tobacco use. Dental hygienists are charged with enlightening the public on the health dangers of this practice and advocating for better regulation of this type of tobacco use.

FURTHER ACTION REQUIRED

The need for additional research on the health risks associated with hookah smoking is clear. Policy interventions can contribute to reducing the popularity of this new type of tobacco use. The World Health Organization recommends examining the following areas related to hookah smoking: evaluation of toxins released by waterpipe use, toxic absorption levels in the body, identification of disease-causing compounds present in hookah smoke, correlation between exposure to compounds and biomarkers, and the generation and facilitation of cessation programs.6

CONCLUSION

Understanding the risk factors associated with waterpipe smoking is key to confronting this public health threat. Additionally, further research is needed to identify related health effects and to determine appropriate interventions. First and foremost, the public needs to be educated about the dangers of this type of tobacco use. When health care professionals and health policy advocates approach hookah smoking as a health threat, evidence-based cessation strategies can be developed and implemented.

REFERENCES

- Aslam HM, Shafaq S, German S, Qureshi WA. Harmful effects of shisha: literature review. Int Arch Med. 2014;7:16.

- Smith-Simone S, Maziak W, Ward K, Eissenberg T. Waterpipe tobacco smoking: Knowledge, attitudes, beliefs, and behavior in two U.S. samples. Nicotine Tob Res. 2008;10:393–398.

- Eissenberg T, Ward KD, Smith-Simone S, Maziak W. Waterpipe tobacco smoking on a U.S. college campus: prevalence and correlates. J Adoles Health. 2008;42:526–529.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Hookahs. Available at: cdc.gov/tobacco/data_ statistics/fact_sheets/tobacco_industry/hookahs. Accessed August 24, 2015.

- Akl EA, Gaddam S, Gunukula SK, Honeine R, Jaoude PA, Iran J. The effects of waterpipe tobacco smoking on health outcomes: a systematic review. Int J Epidemiol. 2010;39:834–857.

- World Health Organization. Waterpipe tobacco smoking: Health effects, research needs, and recommended actions by regulators. Available at: who.int/tobacco/global_interaction/tobreg/Waterpip e%20recommendation_Final.pdf. Accessed August 24, 2015.

- Cobb C, Ward K, Maziak W, Shihadeh AL, Eissenberg T. Waterpipe tobacco smoking: An emerging health crisis in the United States. Am J Health Behav. 2010;34:275–285.

- Knishkowy B, Amitai Y. Water-pipe (narghile) smoking: An emerging health risk behavior. Pediatrics. 2005;116:e113–e119.

- Wolfram RM, Chehne F, Oguogho A, Sinzinger H. Narghile (water pipe) smoking influences platelet function and (iso-)eicosanoids. Life Sci. 2003;74:47–53.

- American Cancer Society. Hookahs—not a safe alternative to cigarettes. Available at: acscan.org/content/wpcontent/uploads/2012/05/Ho okah-Fact-Sheet.pdf. Accessed August 24, 2015.

- Lipkus IM, Eissenberg T, Schwartz-Bloom RD, Prokhorov AV, Levy J. Relationships among factual and perceived knowledge of harms of waterpipe tobacco, perceived risk, and desire to quit among college users. J Health Psych. 2014;19:1525–1535.

- Primack B, Shensa A, Kim K, et al. Waterpipe smoking among US university students. Nicotine Tob Res. 2013;15:29–35.

- Martinasek MP, McDermott RJ, Martini L. Waterpipe (hookah) tobacco smoking among youth. Curr Probl Pediatr Adolesc Health Care. 2011;41:34–57.

- Roskin J, Aveyard P. Canadian and English students’ beliefs about waterpipe smoking: A qualitative study. BMC Public Health. 2009;9:10.

- Neergaard J, Singh P, Job J, Montgomery S. Waterpipe smoking and nicotine exposure: A review of the current evidence. Nicotine Tob Res. 2007;9:987–994.

- Ward KD, Eissenberg T, Gray JN, Srinivas V, Wilson N, Maziak W. Characteristics of US waterpipe users: A preliminary report. Nicotine Tob Res. 2007;9:1339–1346.

- Hammal F, Mock J, Ward MD, Eissenberg T, Maziak W. A pleasure among friends: how narghile (waterpipe) smoking differs from cigarette smoking in Syria. Tob Control. 2008;17:e3.

- Morris DS, Fiala SC, Pawlak R. Opportunities for policy interventions to reduce youth hookah smoking in the United States. Prev Chronic Dis. 2012;9:120082.

- Jawad M, McEwen A, McNeill A, Shahab L. To what extent should waterpipe tobacco smoking become a public health priority? Addiction. 2013;108:1873–1884.

- Sterling KL, Fryer CS, Majeed B, Duong MM. Promotion of waterpipe tobacco use, its variants and accessories in young adult newspapers: a content analysis of message portrayal. Health Edu Res. 2015;30:152–161.

- Sharma G, Nagpal A. Hookah smoking—an ageold modern trend. J Family Med Prim Care. 2015;4:151.

- Dar NA, Bhat GA, Shah IA, et al. Hookah smoking, nass chewing, and oesophageal squamous cell carcinoma in Kashmir, India. Br J Cancer. 2012;107:1618–1623.

- American Lung Association. An Emerging Deadly Trend: Waterpipe Tobacco Use. Available at: lungusa2.org/embargo/slati/Trendalert_Waterpipes. pdf. Accessed August 24, 2015.

- Eissenberg T. AANA journal course: update for nurse anesthetists—Part 3—Tobacco smoking using a waterpipe (hookah): what you need to know. AANA J. 2013;81:308–313.

- Xuan LTT, Van Minh H, Giang KB, et al. Prevalence of waterpipe tobacco smoking among population aged 15 years or older, Vietnam, 2010. Prev Chronic Dis. 2013;10:e57.

- El-Zaatari ZM, Chami, HA, Zaatari GS. Health effects associated with waterpipe smoking. Tob Control. 2015;0:1–13.

- WebMD. Smoking and coronary artery disease. Available at: webmd.com/a-to-z-guides/smokingand- coronary-artery-disease-topic-overview. Accessed August 24, 2015.

- Warnakulasuriya S. Waterpipe smoking, oral cancer and other oral health effects. Evid Based Dent. 2011;12:44–45.

- Munckhof WJ, Konstantinos A, Wamsley M, Mortlock M, Gilpin C. A cluster of tuberculosis associated with use of a marijuana water pipe. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2003;7:860–865.

- Parker DR. A dental hygienist’s role in tobacco cessation. Int J Dent Hyg. 2003;1:105–109.

- American Lung Association. Hookah Smoking: A Growing Threat to Public Health. Available at: lung.org/stop-smoking/tobacco-controladvocacy/ reports-resources/cessation-economicbenefits/ reports/hookah-policy-brief.pdf. Accessed August 24, 2015.

- Agency for Healthcare Research & Quality. Guide to Clinical Preventive Services 2014. Available at: ahrq.gov/professionals/cliniciansproviders/guidelines recommendations/guide/index.html. Accessed August 24, 2015.

- Nakkash R, Khalil J. Health warning labeling practices on narghile (shisha, hookah) waterpipe tobacco products and related accessories. Tob Control. 2010;19:235–239. August 24, 2015.

From Dimensions of Dental Hygiene. September 2015;13(9):46–49.