Tattoos in the Dental Setting

Visible tattoos on oral health professionals can impact patients’ perception of care.

This course was published in the July 2017 issue and expires July 2020. The authors have no commercial conflicts of interest to disclose. This 2 credit hour self-study activity is electronically mediated.

EDUCATIONAL OBJECTIVES

After reading this course, the participant should be able to:

- Discuss the growing prevalence and acceptance of tattooing.

- Identify the implications of oral health professionals displaying tattoos on employment opportunities and patient care.

- Explain the role of gender and age on the perception of visible tattoos.

This permanent symbol of individuality may represent an identity within a group, unique characteristics, life-altering event, expression of beauty, or tolerance for pain.5 A sense of belonging and devotion to anything from a musical band to a religion can be put on permanent display. The freedom of the imagination when it comes to designing a specific tattoo makes this body art unique. The celebration of birthdays, weddings, and the remembrance of deaths can give a sense of joy and peace with the constant imprinted reminder. Lastly, the amount of physical endurance required during the creation of an intricate tattoo displays physical strength and pain tolerance.9,10

Other less likely and evolving motivations behind tattooing should be noted when considering modern-day views. Sociocultural influences include addiction to the art, a need for uniqueness, following a trend, cultural identification, reward for achievement, and impulsive thrill-seeking behaviors.2–6 Even more rare but equally influential are tattoos relating to the field of medicine, such as permanent makeup, corneal tattooing, gastrointestinal tattooing, and scar camouflage.13 Medical alert tattoos provide instructions or the medical status of an individual so a good Samaritan or medical professional can respond accordingly in an emergency. Certain health conditions, such as diabetes and allergies to medications, are commonly found in this category.14 Instructions regarding organ donor status and preferences for life support are also common medical alert tattoos.14

Despite its increasing popularity, individuals with tattoos are still viewed negatively by many in the general public, as well as by employers.15–18 The increased prevalence of body art on employees is a concern for retailers, government agencies, health care corporations, law firms, medical and dental practices, to name a few, as employers struggle to protect their professional images.16–21Because the image of a work setting conveys the company’s beliefs and principles to clients, employers may be hesitant to hire individuals with visible tattoos due to negative stereotypes.19 Potential employees with body art have connotations of risky, unprofessional, nonconforming, substance abusing, and unusual behaviors.1–6 Even the US military, in response to an increase in visible tattoos, has made changes to its tattoo policy.21 Currently, tattoos on the head or face are prohibited in most branches of the military.

TATTOOS IN HEALTH CARE

Because of the increased incidence of health care professionals with visible tattoos, researchers are studying how this form of self-expression is perceived by others.22–25 While societal attitudes are changing, visible tattoos may not be fully accepted in this employment arena. Perceptions of competence, expertise, trustworthiness, and intellectual capabilities may be affected by an individual’s personal appearance.24 It also plays a vital role in first impressions, nonverbal communication, and professional image.22–26 Thomas et al23 concluded that first impressions made by patients occur within the first 12 seconds of their interaction with a health care provider. The patient’s first impression of the dental hygienist is critically important for establishing an effective provider/patient relationship. Within seconds, a patient may assess a dental hygienist’s professionalism, competence, attitude, and trustworthiness, based on his or her appearance and other nonverbal cues. The health care provider/patient relationship is based on mutual respect and trust. If the patient has a negative first impression of his/her oral health professional because of visible tattoos, for example, a trusting relationship may not develop.21 Brosky et al26 found patients’ first impressions of dental students and dental school faculty impacted their comfort and anxiety levels and appearance of the clinician influenced their perceptions of professionalism. Poor patient impressions, whether from verbal or nonverbal issues or based on appearance, may influence the relationship to the extent that therapeutic interventions may be compromised. Ultimately, patients’ first impressions of dental hygienists and their professionalism are linked to appearance.

Studies in nursing generally have found that patients rate nurses with visible tattoos as less professional than nurses without visible tattoos.23–25 However, Thomas et al23 found nursing students to be more accepting of highly tattooed nurses than patients and nursing faculty, suggesting young people have less negative opinions. However, all study participants, including patients, found the nurse in the study with the most tattoos and piercings to be the least caring, skilled, and knowledgeable.23 Other studies also found patients’ perceived nontattooed nurses more favorably than nurses with visible tattoos and tattooed female providers were perceived as less professional than male providers with similar tattoos.15,23–25

Two studies in dentistry evaluated visibly tattooed dental hygienists on the basis of professionalism.22,27 Quiros et al22 determined Virginia dentists’ perceptions of visibly tattooed dental hygienists. Participants were asked about their perceptions of visibly tattooed dental hygienists with various sizes of tattoos sizes in regard to being ethical, responsible, competent, hygienic, and professional. Results indicated that the visibly tattooed dental hygienist, despite the tattoo’s size, was perceived as significantly less hygienic and professional when compared with dental hygienists without visible tattoos. Dentists were most concerned with the image of their practice in terms of patients’ receptiveness toward dental hygienists with visible tattoos. In addition, dentists rated the dental hygiene model in the study who had no tattoos as the most favorable in each of the attributes evaluated. The authors concluded visible tattoos could negatively affect employment opportunities for dental hygienists.22 Verissimo et al27 researched patients’ perceptions of visibly tattooed dental hygienists of varying size based on professionalism. Dental hygienists with large visible tattoos were perceived as significantly less professional, and patients were less likely to refer patients to the practice or return for visits. However, as with the Quiros study, the dental hygienists with no tattoos scored the most favorable in all attributes evaluated.22,27

GENDER AND AGE

Gender is also important, as it influences perceptions of tattooed individuals.7,8 In female-dominated professions, this is a significant concern. Boultinghouse28 found participants of all ages rated a female nurse with visible tattoos less professional when compared with a female nurse without visible tattoos, but the male nurse with visible tattoos was perceived the same as the male nurse without visible tattoos. Another study evaluating perceptions of tattooed women compared with nontattooed women found that tattooed women were perceived as less attractive, more sexually promiscuous, and heavier drinkers by male and female undergraduate students.7 Westerfield et al24 found patients’ perceived visibly tattooed female health care providers as less professional than male providers with similar tattoos. In a study that evaluated women with tattoos by manipulating size and visibility of tattoos in hypothetical descriptive cases, participants of both genders had more negative perceptions regarding women with visible tattoos compared with men.23 This gender bias may affect the acceptance and hiring of female health care providers in the workplace. Female dental hygienists with visible tattoos may be perceived negatively based solely on appearance.

In addition to gender bias, age may contribute to differences in perceptions regarding tattooed individuals.12,22 According to the Pew Research Center, 64% of people age 65 and older and 51% of people between the ages of 50 and 64 view the increased popularity of tattooing as a “change for the worse,” while 56% of people age 50 and younger noted the increased prevalence has not significantly impacted society.12 Furthermore, six in 10 women age 50 and older viewed the increased popularity in tattooing as a “change for the worse,” reflecting a greater age difference in perceptions compared with men.11 More than one-third of young adults age 18 to 25 have at least one tattoo, compared to only 13% of baby boomers.11 Older participants perceived tattooed individuals more negatively, especially regarding intelligence and honesty. While older Americans represent a much lower percentage of tattooed individuals, they are more likely to hold traditional stereotypes.12 These demographics are important to consider when evaluating the effects of tattoos on dental hygiene, especially in regards to interpersonal relationships with older adults.

EMPLOYMENT RAMIFICATIONS

Among the Millennial generation, Foltz29 found 86% of students surveyed believed any student with visible tattoos would have a hard time finding employment and 95% of surveyed students would make sure tattoos were invisible during an interview in a corporate setting. Even though students were aware that a tattoo may negatively affect employment opportunities in corporate America, 50% of the students surveyed were still considering one. Despite students’ beliefs that tattoos presented an obstacle to job employment, the ability to cover up tattoos was the deciding factor for actually getting a tattoo.29

An employer’s prejudice to tattooed interviewees depends on several factors, including tattoo location and type, place of employment, involvement with customers, and, most important, the perceptions of the company’s clientele.18 Whether a hiring manager believes tattoos are positive or negative is less important than his or her perceptions of what clients will perceive about someone with a tattoo. Administrators have legal rights to enforce dress codes and appearance policies when it is a concern of safety or a threat to the company’s reputation. As visible tattoos become more conventional in today’s health care settings, it is vital to clearly address tattoos in written dress code policies before an applicant is hired. Administrators may face legal issues trying to enforce their terms of professional image without written documentation.18

Mitchell et al30 described these challenges relating to tattoos in three parts of the Civil Rights Act of 1964. The section on the Civil Rights Act and Religion highlights the role discrimination plays when an employee’s tattoo has a religious affiliation. While there is no legal requirement to impose an appearance policy, maintaining a consistently enforced written protocol can legally help a company defend against claims of discrimination. This written documentation can protect the integrity of the company and promote a healthy, prosperous work environment.30 Under the Civil Rights Act and Gender, Mitchell et al30 emphasized the District of Columbia’s legal decree against discrimination in the workplace. The District of Columbia official codes define personal appearance as visible characteristics associated with dress and personal grooming, despite sex of the individual. Under these parameters, tattooing may likely be accommodated. The third challenge noted under federal legislation reiterates consistent reinforcement of dress codes and appearance policies in accordance to the Disabilities Act and National Labor Relations Act. Importantly, an administrator may legally enforce visible tattoo policies even if this conflicts with an individual’s personal or cultural expression.

Traditional differences in perceptions will likely fade as visible tattoos become more mainstream.31,32 Dental hygienists working in offices that cater to older populations may not be perceived positively if they have visible tattoos, possibly impacting their credibility. However, displaying a tattoo may be less impactful in an office that caters to young patients or may even enhance the image of the practice and clinician. There are potential advantages with colorful or interesting visible tattoos. For example, they could serve as conversation starters with certain patients. Moreover, patients with tattoos may relate more to a health care provider with a tattoo.

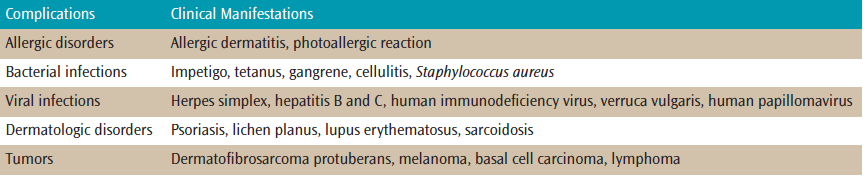

For dental hygienists contemplating body art, considering what professional image they want to portray to current and future employers, as well as patients, should be part of the decision-making process before obtaining a tattoo. Tattoo remorse is on the rise, with one in eight (14%) of the 21% of American adults who have tattoos regretting their decision.11 Laser removal is available but it can be time-consuming, painful, and costly. Oral health professionals should consider avoiding tattoos that are likely to offend or distract their employers and/or patients. For example, a flower on the wrist or a heart behind the ear will be perceived differently than a firearm. Additionally, the size and placement of the tattoo should be considered carefully. Choosing a location that is not visible when wearing scrubs or that can be easily covered may be prudent. Oral health professionals may want to avoid tattoos on the face, hands, neck, and forearms because of their visibility. Understanding potential complications and dermatologic disorders that could arise with tattooing is also important and each individual should evaluate how these could impact his or her current and future practice (Table 1).33

Another consideration is the long-term impact of the ink and its possible toxicokinetic effects on the body.34 Emerging research suggests the nanoparticles in black tattoo ink are absorbed into cells through phagocytosis.34 White blood cells carry the nanoparticles to adjoining lymph nodes, where the ink collects but is not metabolized. This process may suppress the immune system, leaving the body susceptible to opportunistic infections. However, more research is needed to fully evaluate the toxicokinetic risk of tattoo ink chemicals in the body.34

CONCLUSION

The professional image of oral health professionals should communicate to patients that they will provide ethical, professional, competent, and trustworthy treatment. For many patients, visible tattoos are not consistent with these characteristics. While some segments of the population are more accepting of self-expression, research suggests the professional image and credibility of a dental hygienist are negatively impacted by the presence of visible tattoos.22,27 Lack of credibility in a dental hygienist may negatively impact a dental office’s overall practice image and perceived level of patient care.27

Thomas et al23 recommend that if nurses want to be perceived as skilled and knowledgeable, they should limit the amount of visible body art. Dental hygienists might consider adopting the same idea to promote a more professional appearance while fostering positive relationships with patients.27 Dental office polices limiting visible tattoos may minimize negative perceptions and foster positive interpersonal relations and patient outcomes.27 The presence of visible tattoos may influence hiring decisions and the opinions of potential employers.22 On the other hand, as the Millennial population will be the ones creating office policies and making hiring decisions in the future, existing attitudes and policies regarding visible tattoos may become less restrictive.

REFERENCES

- Doss K, Ebesu Hubbard AS. The communicative value of tattoos: the role of public self-consciousness on tattoo visibility. Communication Research Reports2009;26(1):62–74.

- Totten JW, Lipscomb TJ, Jones MA. Attitudes toward and stereotypes of persons with body art: implications for marketing management. Acad Mark Stud J. 2009;13:77–96.

- Laumann AE, Derick AJ. Tattoos and body piercings in the united states: a national data set. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;55:413–421.

- Roberts JD. Secret Ink: tattoo’s place in contemporary american culture. J Am Cult. 2012;35:153–165.

- Carmen RA, Guitar AE, Dillon HM. Ultimate answers to proximate questions: the evolutionary motivations behind tattoos and body piercings in popular culture. Rev Gen Psychol. 2012;16:134–143.

- Larsen G, Patterson M, Markham L. A deviant art: Tattoo-related stigma in an era of commodification. Psychology & Marketing. 2014;31(8):670–681.

- Swami V, Furnham A. Unattractive, promiscuous and heavy drinkers: Perceptions of women with tattoos. Body Image. 2007; 4(4);343-352.

- Baumann C, Timming AR, Gollan PJ. Taboo tattoos? A study of the gendered effects of body art on consumers’ attitudes toward visibly tattooed front line staff. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services. 2016;29;31–39

- Tiggemann M, Hopkins L. Tattoos and piercings: bodily expressions of uniqueness. Body Image. 2011;8(3):245–250.

- Heywood W, Patrick K, Smith AM, et. al. Who gets tattoos? Demographic and behavioral correlates of ever being tattooed in a representative sample of men and women. Ann Epidemiol. 2012;22(1);51–56.

- Harris Interactive. Tattoo Takeover: Three in Ten Americans Have Tattoos, and Most Don’t Stop at Just One. Available at:theharrispoll.com/health-and-life/Tattoo_Takeover.html. Accessed May 30, 2017.

- Heimlich R. Tattoo Gen Nexters. Available at: pewresearch.org/daily-number/tattooed-gen-nexters/. Accessed May 30, 2017.

- Vassileva S, Hristakieva E. Medical applications of tattooing. Clin Dermatol. 2007;25:367–374.

- Kluger N, Aldasouqi S. A new purpose for tattoos: Medical alert tattoos. Presse Med. 2013;42:134–137.

- Jones N, Hobbs M. Tattoos and piercings—are the compatible with the workplace? Nurs Resident Care. 2015;17:103–104.

- Wittmann-Price RA, Gittings KK, Collins KM. Nurses and body art: what’s your perception? Nurs Manag. 2012;4:44-47.

- Williams DJ, Thomas J, Christensen, C. You need to cover your tattoos!: reconsidering standards of professional appearance in social work. Social Work. 2014;59:373–375.

- Timming AR. Visible tattoos in the service sector: a new challenge to recruitment and selection. Work Employ Soc. 2014;29:60–78.

- Dean DH. Consumer perceptions of visible tattoos on service personnel. Manag Serv Q. 2010;20:294–308.

- Mishra A, Mishra A. Attitude of professionals and students towards professional dress code, tattoos and body piercing in the corporate world. International Journal of Innovative Research and Development. 2015;4(4):324–331.

- Faram M. The Navy just approved the military’s best tattoo rules. Available at:navytimes.com/story/military/2016/03/31/navy-just-approved-militarys-best-tattoo-rules/82425974/. Accessed May 30, 2017.

- Quiros C, McCombs G, Tolle SL, Arndt A. The association between dental hygienists with visible tattoos and professionalism in the commonwealth of Virginia. Int J Evid Based Pract Dent Hygienist. 2016;2:129–134.

- Thomas CM, Ehret A, Ellis B, Colon-Shoop S, Linton J, Metz S. Perception of nursing caring, skills, and knowledge based on appearance. J Nurs Admin. 2010;40:489–497.

- Westerfield HV, Stafford AB, Speroni KG, Daniel MG. Patients’ perceptions of patient care providers with tattoos and/or body piercings. J Nurs Admin. 2012;42;160–164.

- Merrill K. Professional dress vs. employee diversity: patient perceptions of visible tattoos and facial piercings. Available at:stti.confex.com/stti/congrs15/webprogram/Paper71570.html. Accessed May 30, 2017.

- Brosky ME, Keefer OA, Hodges JS, Pesun IJ, Cook G. Patient perceptions of professionalism in dentistry. J Dent Educ. 2003;67:909–915.

- Verissimo A, Tolle SL, McCombs G, Arndt A. Assessing dental clients’ perceptions of dental hygienists with visible tattoos. Can J Dent Hyg. 2016;50;103–109.

- Boultinghouse DM. Visible tattoos and professional nursing characteristics: a study on how appearance affects the perception of essential qualities of nurses. Available at: http://scholarworks.uark.edu/nursuht/40. Accessed May 30, 2017.

- Foltz KA. Millenial’s perception of tattoos: self-expression or business faux pas? Coll Stud J. 2014;48;589–602.

- Mitchell MS, Koen CM, Darden SM. Dress codes and appearance policies: challenges under federal legislation, part 3: title vii, American with Disabilities Act, and National Labor Relations Act. Health Care Manager. 2014;33(2);136–148.

- Swami V, Tran US, Kuhlmann T, Stieger S, Gaughan H, Voracek M. More similar than different: Tattooed adults are only slightly more impulsive and willing to take risks than nontattooed adults. Pers Indiv Diff. 2015;88:40–44.

- Swami V, Gaughan H, Ulrich TS, Kuhlmann T, Stieger S, Voracek M. Are tattooed adults really more aggressive and rebellious than those without tattoos? Body Image. 2015;15:149–152.

- Khunger N, Molpariya A, Khunger A. Complications of tattoos and tattoo removal; stop and think before you ink. J Cutantan Aesthet Surg. 2015;8:30–36.

- Neale P, Stalter D, Tang J, Escher B. Bioanalytical evidence that chemicals in tattoo ink can induce adaptive stress responses. J Hazard Mater. 2015;296:192–200.

Featured photo by PHOTODISC/GETTY IMAGES PLUS; GIANLUCABARTOLI/ISTOCK/GETTY IMAGES PLUS

From Dimensions of Dental Hygiene. July 2017;15(7):40-43.