Effects of Synthetic Cannabinoid Use

Oral health professionals need to be aware of the systemic and oral health effects of the substances in this class of drugs.

This course was published in the July 2017 issue and expires July 2020. The authors have no commercial conflicts of interest to disclose. This 2 credit hour self-study activity is electronically mediated.

EDUCATIONAL OBJECTIVES

After reading this course, the participant should be able to:

- Define synthetic cannabinoids and their drug classification.

- Discuss the adverse effects of synthetic cannabinoid use.

- Identify the rising prevalence of medical events related to the toxicity of this class of drugs.

- Note the oral health implications of synthetic cannabinoid use.

Synthetic cannabinoids are man-made drugs manufactured to resemble the chemicals in marijuana plants.1 The chemicals are sprayed onto plant material, which is then smoked or converted into liquid to be vaped, similar to how marijuana is used.2 Synthetic cannabinoids may be purchased legally because drug manufacturers constantly change the chemical structure to circumvent drug laws.1,3 While marketed as safe and legal alternatives to marijuana, synthetic cannabinoids exert significant effects on the brain, causing a host of negative side effects, including acute toxicity and possible death.1–12

The use of synthetic cannabinoids is undetectable by traditional drug testing, giving it a reputation as a “legal high” and making it an attractive substitute to marijuana.1,3 Oral health professionals are in a unique position to educate patients and the public about synthetic cannabinoid use and its adverse effects, including oral health effects, while also providing resources and referral for intervention.

DRUG CLASSIFICATION AND METHODS OF CONSUMPTION

Synthetic cannabinoids are classified as new psychoactive substances (NPS), which are recently introduced mind-altering chemicals designed to imitate common illegal drugs.2These synthetic versions mimic the pharmacological effects of the original substance, while avoiding classification as illegal.2,13–16

A variety of consumption methods are available for synthetic cannabinoids, such as smoked in joints and/or pipes, ingested, used in tea, and vaporized and inhaled in e-cigarettes or through the mouth and nose. Manufacturers sell these herbal incense products in colorful foil packages and liquid incense products, marketing them under myriad names to appeal to young people. Synthetic cannabinoids may be called K2, spice, joker, black mamba, kush, and chronic.2,13 Most NPSs are manufactured in China without regulation and then smuggled into the United States.13,15 They are sold via the internet, in head shops (stores selling drug-related paraphernalia), smoke shops, convenience stores, and gas stations.13,14 NPS use is popular among athletes, soldiers, and parolees, because they can be consumed without being detected on the mandatory drug tests common among these populations.7,16

HISTORY

Decades ago, synthetic cannabinoids were created and used for experimental and pharmaceutical purposes. Currently, two cannabinoid-based drugs—dronabinol and nabilone—are approved by the federal Food and Drug Administration and legally produced and prescribed.10 Ingested in pill form, dronabinol and nabilone are prescribed to address the vomiting/nausea caused by cancer therapy. Dronabinol is also used to improve the appetite of those with the human immunodeficiency virus.

The types of synthetic cannabinoids used recreationally include the HU-210 series developed by Hebrew University of Jerusalem in the 1960s; the cyclohexyl phenol series developed and named after Charles Pfizer of Pfizer Pharmaceuticals in the 1970s; and the JWH series developed and named for John W. Huffman, PhD, of Clemson University in the 1990s.10,14 Synthetic cannabinoid use for nonmedical purposes became popular in Europe in 2004 and then in the US in 2008.1,3,9,15

Since 2009, more than 300 NPSs have been identified, with approximately 95 different synthetic cannabinoids being sold as legal alternatives to cannabis.13 A primary misconception is that these drugs are natural, legal, safe, and produce fewer side effects than marijuana.15

PHARMACODYNAMICS

Most synthetic cannabinoids have a greater binding affinity to the cannabinoid receptor CB1 receptor than does 9-tetrahydrocannabinol (THC)—the primary psychoactive compound in the cannabis plant. Synthetic cannabinoids also have a greater affinity to the CB1 receptor than to the CB2 receptor.16 Cannabinoid receptors, located throughout the body, are part of the endocannabinoid system, which is involved in a variety of physiological processes, including appetite, pain/sensation, mood, and memory.15,16 When synthetic cannabinoids activate CB1 (psychoactive effects) or CB2 receptors (anti-inflammatory effects), they change the way the body functions. In vitro and animal in vivo studies show synthetic cannabinoid pharmacological effects are two times to 100 times more potent than THC.16 Synthetic cannabinoids produce physiological and psychoactive effects similar to THC but with greater intensity, which may result in medical and psychiatric emergencies.

Due to the negative effects of these drugs, many users prefer cannabis over synthetic cannabinoids.16 Long-term and residual effects are unknown, and there is a need for drug-detection tests made specifically for the detection of synthetic cannabinoids.16,17

SYSTEMIC HEALTH EFFECTS AND TOXICITY

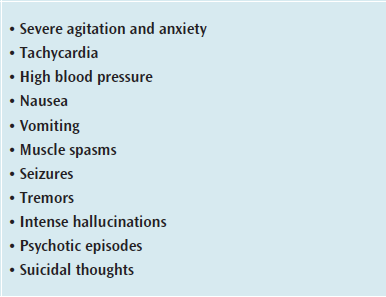

Many federal, state, and local government officials have determined that synthetic drug use is a public health threat. Users don’t know what they are consuming, leaving them unaware of health or addiction risks.9,12 Synthetic cannabinoids produce similar effects to cannabis, such as elevated mood, relaxation, altered perception, and symptoms of psychosis, while also bearing the risk of serious adverse health effects (Table 1).2,12,13

In 2010, the American College of Medical Toxicology established the ToxIC Case Registry to survey and research toxicology.9Participating sites record basic data on patients who have been treated by medical toxicologists. Among 456 cases of synthetic cannabinoid intoxication treated by US medical toxicologists between 2010 and 2015, 277 noted synthetic cannabinoids as the sole toxicologic agent.9 Of these cases, three deaths were attributed solely to synthetic cannabinoids, in addition to two deaths attributed to exposure to multiple agents. During this same period, the number of synthetic cannabinoid poisonings increased across the US.9

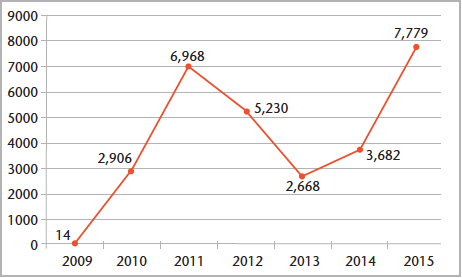

According to the American Association of Poison Control Centers (AAPCC), poison control centers around the US received 7,779 calls related to synthetic cannabinoid substances in 2015, more than double the number of calls received in 2014 (Figure 1).12 The number of calls decreased from 2011 to 2013, most likely due to the passage of the Synthetic Drug Abuse Prevention Act of 2012. The act added certain synthetic cannabinoids to Schedule I of the Controlled Substances Act.14 Current AAPCC data for 2017 indicate 186 reports of exposure to synthetic cannabinoids made during the month of January.12

States across the country have been experiencing an uptick in adverse medical events associated with synthetic cannabinoid use. In September 2013, 76 patients—mostly young men—visited emergency departments in Aurora, Colorado, due to toxic exposure to black mamba, a type of synthetic cannabinoid.6 Those affected experienced altered mental status and tachycardia followed by brachycardia. Most were treated in the emergency department, but seven required admission to intensive care units. Product analysis confirmed the offending substance was a molecule known as ADB-PINACA, a novel synthetic cannabinoid.6 Exposure to this substance was associated with neurotoxicity and cardiotoxicity; however, evolving types of synthetic cannabinoids have been associated with seizures, ischemic stroke, cardiac toxicity, and acute kidney failure.6,9,11,14,16

From April 2 to May 3, 2015, the University of Mississippi Medical Center (UMMC) reported 721 reported cases associated with synthetic cannabinoid use, including nine deaths. Patients were mostly men and ranged in age from 14 to 62 (median age of 31).5Most patients were treated and released by the UMMC emergency department, but 13 were admitted to general inpatient services and 12 were admitted to intensive care units. Vital signs information was available for 115 patients, with 48 reporting tachycardia (heart rate >100 beats per minute) and 35 noting elevated (>140 mmHg) systolic blood pressure. A portion of patients exhibited aggressive or violent behavior, agitation/aggression, depression, or confusion.

Anchorage, Alaska, experienced an outbreak of adverse reactions related to synthetic cannabinoid use from July 2015 to March 2016. During this period, 1,351 emergency department visits were due to synthetic cannabinoid use. The investigation found 11 different synthetic cannabinoids chemicals circulating during the outbreak. Passage of ordinance AO2015-123(S) raised criminal penalties associated with possession, use, and sale of synthetic cannabinoids, resulting in a significant decline in the number of patients seeking treatment for synthetic cannabinoid use following its passage.8

New York City has also experienced an increase in synthetic cannabinoid-related emergency department visits, despite a notable decrease in use following passage of legislation in 2015 that makes it illegal to possess, sell, offer to sell, or manufacture synthetic cannabinoids, and the implementation of other public health campaigns.4 Since January 2015, the city’s Department of Health and Mental Hygiene has noted more than 8,000 synthetic cannabinoid-related emergency department visits with 10 documented mortalities; nine of which involved multiple substances.4 Approximately 90% of those affected were men and 99% were age 18 or older with a median age of 37.

In 2016, a team of researchers from the University of Arkansas received a $2.7 million grant from the National Institutes of Health and National Institute on Drug Abuse to conduct the first comprehensive study on the dangers posed by synthetic cannabinoids.18 The purpose of the 5-year study is to determine the toxicity of man-made cannabinoids, possible antidotes for toxicity, and create an educational campaign promoting the fact that synthetic cannabinoids do not provide a safe alternative to marijuana.18

PROCESS OF CARE AND ORAL HEALTH IMPLICATIONS

The dental hygiene process of care includes assessment, dental hygiene diagnosis, planning, implementation, evaluation, and documentation.19 During the assessment phase, oral health professionals should ask questions, such as whether the patient uses any form of tobacco or marijuana, frequency and amount of use, and interest in quitting. Other screening tools include the Cage Questionnaire20 and the Five A’s Model (Ask, Advise, Assess, Assist, and Arrange).21 These are most effective when used while taking a routine medical history.

Health care providers need to be familiar with synthetic cannabinoids so they can provide information and referral for treatment and/or intervention. Indicators of recent synthetic cannabinoid use may include conjunctival injection (red sclera); breath with a smoky, chemical smell; tachycardia; hypertension; lightheadedness; and headache.22 Similar to tobacco and marijuana use, patients who consume synthetic cannabinoids are at increased risk of xerostomia, which is associated with increased caries risk, staining, and oral malodor.23 Chronic smoking can create inflammation of the oral epithelium, leukoplakia, periodontal diseases, and delay wound healing.23Marijuana users tend to have poor oral hygiene compared with nonusers and this may also be true for synthetic cannabinoid users.21

Vital signs are often increased with marijuana use and careful intra- and extraoral examination may include signs, such as lack of oral hygiene; dilated pupils; red, inflamed, or bloodshot eyes; mucosal dryness; heavy biofilm; moderate to severe gingival inflammation; and caries.22 Patients with substance abuse problems tend to delay dental care, which is reflected in their oral health status.21 Following an assessment, the next steps include composing a dental hygiene diagnosis, identifying priorities based on the patient’s needs, and discussing these findings with the patients. Patients should be educated on the importance of biofilm control and how to effectively accomplish this at home. Oral health professionals must be aware of the characteristics that suggest possible use of synthetic cannabinoids and provide an appropriate dental hygiene care plan and education regarding the negative health effects of usage.

PREVENTION AND TREATMENT PROGRAMS

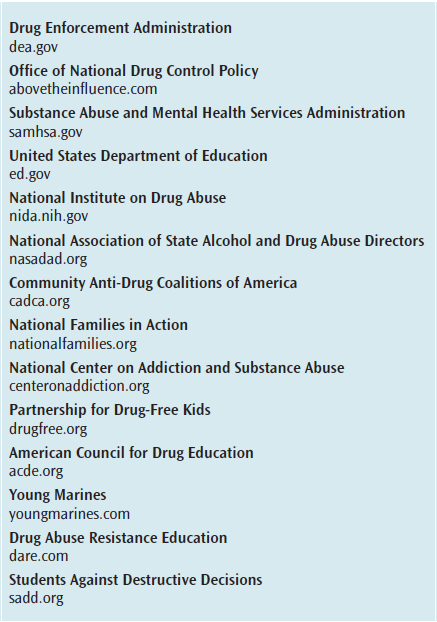

The federal government has instituted several national drug prevention programs designed to reach targeted populations through public service announcements, grant opportunities, educational programs, and the sharing of expertise. Many local and state governments have also created prevention programs tailored to address specific problems and needs. Law enforcement agencies, military branches, businesses, faith-based institutions, civic organizations, and private foundations are also active forces in drug abuse prevention.13 Table 2 provides a list of some of these resources.

Oral health professionals should compile a list of local drug prevention and treatment agencies and programs to provide to patients. A 1-page fact sheet on synthetic cannabinoid use, similar to educational resources regarding tobacco/smoking, may be disseminated in dental practices.

CONCLUSION

The increasing popularity of synthetic cannabinoids use requires oral health professionals to be aware of the health effects of these substances. By remaining up-to-date on current trends of alternative recreational drug use, oral health professionals will be better able to detect early clinical signs of unhealthy lifestyles, including potential synthetic cannabinoid use and provide referrals and intervention resources. Clinicians should conduct a thorough medical and dental history that assesses social behaviors in addition to vital signs and performing an extraoral and intraoral examination. This will assist in implementing appropriate treatment and intervention strategies. Ultimately, the goal of oral health professionals is to provide appropriate oral treatment; educate and improve patients’ health literacy; and assist in motivating patients to address substance misuse in order to improve oral and systemic health outcomes.21,23

REFERENCES

- European Monitoring Center for Drugs and Drug Addiction. New Psychoactive Substances in Europe. Available at:emcdda.europa.eu/attachements.cfm/ att_235958_EN_TD0415135ENN.pdf. Accessed June 8, 2017.

- National Institute on Drug Abuse. Drug Facts: Synthetic Cannabinoids. Available at: drugabuse.gov/publications/drugfacts/synthetic-cannabinoids. Accessed June 8, 2017.

- United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime. Global Synthetic Drugs Assessment. Available at:unodc.org/documents/scientific/2014_Global_Synthetic_Drugs_Assessment_web.pdf. Accessed June 8, 2017.

- New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene. K2—Synthetic Cannabinoids. Available at: nyc.gov/site/doh/health/health-topics/k2.page. Accessed June 8, 2017.

- Kasper AM, Ridpath AD, Arnold JK, et al. Severe illness associated with reported use of synthetic cannabinoids—Mississippi, April 2015. MMWR. Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2015;64:1121–1122.

- Monte AA, Bronstein AC, Cao DJ, et al. An Outbreak of exposure to a novel synthetic cannabinoid. N Engl J Med. 2014;370:389–390.

- Mathai D, Gordon M, Muchmore P, et al. Paradoxical increase in synthetic cannabinoid emergency–related presentations after a citywide ban: Lessons from Houston, Texas. Bulletin of the Menninger Clinic. 2016;80(4):357–370.

- Springer YP, Gerona R, Scheunemann E, et al. Increase in adverse reactions associated with use of synthetic cannabinoids—Anchorage, Alaska, 2015–2016. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2016;65:1108–1111.

- Riederer, AM, Campleman, SL, Carlson, RG, et al. Acute poisonings from synthetic cannabinoids—50 US toxicology investigators consortium registry sites, 2010-2015. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2016;65:692–695.

- Young AC, Schwarz E, Medina G, et al. Cardiotoxicity associated with the synthetic cannabinoid, K9, with laboratory confirmation. Am J Emerg Med. 2012;30:1320.

- Zaurova M, Hoffman R.S, Vlahov D, et al. Clinical effects of synthetic cannabinoids receptor agonists compared with emergency department patients with acute drug overdose. J Med Toxicol. 2016;12:335–340.

- American Association of Poison Control Centers. Synthetic Cannabinoids. Available at: aapcc.org/ alerts/synthetic-cannabinoids. Accessed June 8, 2017.

- US Department of Justice, Drug Enforcement Administration. Drugs of Abuse: A DEA Resource Guide. Available at:dea.gov/pr/multimedia-library/publications/drug_of_abuse.pdf. Accessed June 8, 2017.

- Sacco LN, Finklea K. Synthetic Drugs: Overview and Issues for Congress. Available at: fas.org/sgp/ crs/misc/R42066.pdf. Accessed June 8, 2017.

- Lisi D. Patients may be using synthetic cannabinoids more than you think. J Emerg Med Serv. 2014;39:1–6.

- Castaneto MS, Gorelick DA, Desrosiers NA, et al. Synthetic cannabinoids: Epidemiology, pharmacodynamics, and clinical implications. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2014;144:12–41.

- Spaderna M, Addy PH, D’Souza, DC. Spicing thing up: synthetic cannabinoids. Psychopharmacology (Berl). 2013;228:525–540.

- The Cannabist. Researchers receive $2.7M federal grant to study synthetic cannabinoids. Available at:thecannabist.co/2016/06/29/synthetic-marijuana-research-grant/57124. Accessed June 8, 2017.

- American Dental Hygienists’ Association. Standards for Clinical Dental Hygiene Practice. Available at:adha.org/resources-docs/2016-Revised-Standards-for-Clinical-Dental-Hygiene-Practice.pdf. Accessed June 8, 2017.

- Ewing JA. Detecting alcoholism: the CAGE questionnaire. JAMA. 1984;252:905–907.

- Wilkins E. Clinical Practice of the Dental Hygienist. 12th ed. Philadelphia: Wolters Kluwer; 2017.

- Weaver MF, Hopper JA, Gunderson EW. Designer drugs 2015: assessment and management. Addict Sci Clin Pract. 2015;10:8.

- Ditmeyer MM, Demopulos CA, Mobley C. Under the influence. Dimensions of Dental Hygiene. 2013;11(7):41–43.

Featured photo courtesy of DARRENMOWER/E+/GETTY IMAGES PLUS

From Dimensions of Dental Hygiene. July 2017;15(7):36-39.