ISAYILDIZ / ISTOCK / GETTY IMAGES PLUS Supporting

ISAYILDIZ / ISTOCK / GETTY IMAGES PLUS Supporting

Supporting Implant Health

Effective implant maintenance is key to ensuring the success of this popular therapy.

Thirty years ago, dental implants were placed and maintained primarily at dental offices that specialized in implantology.1 Today, implant maintenance is handled in general dental offices as well as specialty practices. As the popularity of implant therapy has grown, so has the prevalence of peri-implant diseases. The prevalence of peri-implant mucositis is estimated at 30% to 43%, and the prevalence of peri-implantitis is approximately 12% to 22%.2,3 With such a large number of patients investing in implant therapy, the standard of care for peri-implant maintenance must remain high.

Etiology, types of bacteria present, host response, systemic conditions, and other local risk factors—such as faulty restoration margins—all impact the success or failure of dental implants. Peri-implant mucositis is an inflammatory response in the mucosa surrounding the implant similar to gingivitis. Peri-implantitis encompasses mucosal inflammation in addition to crestal bone loss.2 In order to support implant health, peri-implant assessment, appropriate instrumentation, and self-care instruction are key.

Assessment

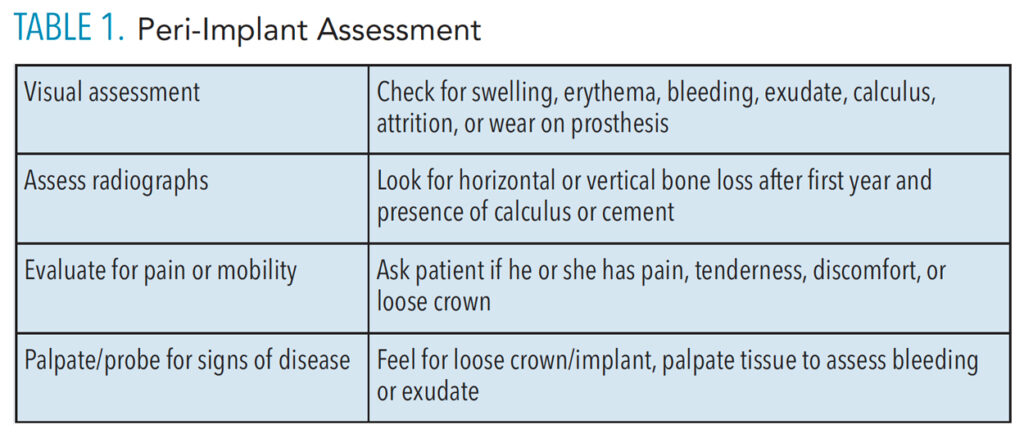

A thorough review of the patient’s medical and dental history, including systemic conditions and history of periodontal therapy, is key to risk assessment for peri-implant diseases (Table 1). Research shows the same bacteria are found in periodontal and peri-implant pockets.4 When bacteria implicated in periodontal diseases are found in peri-implant pockets, similar effects are seen in the soft tissues. As such, implant maintenance appointments to assess plaque control and gingival health and remove biofilm are necessary at least every 6 months and possibly more frequently depending on the patient’s needs.2,3,5 Costa et al6 found that patients who did not follow the recommended preventive maintenance plan were at increased risk for peri‐implantitis compared with those who adhered to the recare plan.

While periodontal assessment is required, guidelines on healthy peri-implant indices—such as pocket depths, bleeding on probing, and whether to use metal or plastic instruments—are hotly debated. Almost 20 years ago Chen and Darby7 recommended the use of plastic probes over metal to reduce the risk of scratching the implant surface. Renvert and Polyzois8 also suggest using a plastic probe because its flexibility enables the clinician to manuever it around the prosthesis of the implant to prevent damaging the peri-mucosal seal.

Some researchers assert that healthy peri-implant pockets should be 5 mm or less with no bleeding or suppuration on probing.1,2 Berglundh et al,9 however, note that peri-implant disease can exist with reduced bone support and healthy probing depths can be greater than 5 mm. Coli and Sennerby10 recommend against using periodontal probing as an indicator of disease, suggesting the peri-implant tissues may cause false bleeding on probing and healthy implant tissue may also present with pocket depths greater than 6 mm. While caution should always be used when probing to avoid damaging the mucosal attachment around an implant, the risk of iatrogenic damage remains.

Other assessments of peri-implant health include clinical indices, such as texture, color, biofilm accumulation (Figure 1), bleeding on probing, suppuration, mobility, radiographs to assess bone levels, and microbiology to asses flora in the peri-implant pocket.7 Coli and Sennerby10 suggest that clinical visual inspection of oral hygiene; palpitation and inspection of tissues while looking for swelling, bleeding, or suppuration; and radiographs to assess crestal bone levels are more definitive than periodontal probing to diagnose implant health.

Radiographs to evaluate crestal bone levels over time are necessary. Studies show that healthy implants can have a remodeling or horizontal bone loss of up to 1.5 mm in the first year post-implant therapy, and no more than 0.2 mm of vertical bone loss in subsequent years.2,5 Iatrogenic factors—such as the presence of cement, gaps between fixture and prosthesis, and adjacent implants creating larger interproximal spacing—also need to be considered when assessing peri-implant health.5,11

As the popularity of implant therapy has grown, so has the prevalence of peri-implant diseases.

Instrumentation Protocol

The treatment plan for a peri-implant infection is different than what is needed to address a periodontal infection, even though biofilm management is necessary in both types of treatment.

Studies show that stainless steel instruments can scratch, roughen, or cause a galvanic reaction with the implant or abutment during mechanical debridement and may increase the surface area available for biofilm management.12,13 While using plastic scalers or burs to remove biofilm or calculus from implant surfaces or abutments is common, they have myriad limitations due to their fragility, difficulty in adapting to the implant restoration, and propensity to leave residue behind.2,7,12,13

Acceptable for implant debridement, carbon fiber and graphite instruments are softer than titanium implants, but they are difficult to adapt to the implant restoration and may break easily.12,13 Titanium implant scalers are similar in hardness to the implant, will not scratch the implant, and are thin enough to adapt to the implant restoration.5,12 Safe to use in implant therapy, titanium implant scalers receive mixed reviews on their effectiveness.8

Ultrasonic Instrumentation

Ultrasonic instrumentation is a fundamental tool in the periodontal therapy armamentarium. Questions remain, however, about its effectiveness in implant therapy as well as concerns regarding its ability to maintain the integrity of the implant surface and peri-mucosal seal when used to treat peri-implant diseases.

The use of an ultrasonic insert/tip with an implant-specific plastic cover on low power is safe for implants.2,8,12 The goal is to disrupt and reduce the bacterial load through lavage without compromising the implant surface; however results are mixed.5 Renvert and Polyzois8 state there is no evidence supporting that decontamination with these methods reduces pocket depth. Some research using implant scalers and ultrasonic devices has demonstrated reduction in bleeding and plaque scores 6 months after treatment, but probing depths did not improve.8

Polishing

Selective supragingival rubber cup polishing is acceptable on implant structures to remove stain and to deplaque. However, only nonabrasive prophy pastes, such as aluminum or tin oxide, should be used. Prophy paste containing acidulated phosphate fluoride (APF) should be avoided.2,5,13

Subgingival air polishing may leave residue that negatively impacts tissue healing and bone regeneration.5 Air polishing with sodium bicarbonate is contraindicated in implant therapy because it will damage the titanium implant structures. Powder air polishing using a low abrasive glycine powder with an implant tip may effectively remove biofilm and treat implant mucositis without damage to implant surfaces.5,12 The safety of supra- and subgingival air polishing around implants remains unknown, as these techniques may damage the implant’s porcelain surface or create pits or irregularities on the titanium.13

Implant maintenance appointments to assess plaque control and gingival health and remove biofilm are necessary at least every 6 months…

Laser Therapy and Antimicrobials

The use of lasers may be helpful in reducing bacterial levels. Hard and soft tissue lasers are effective at reducing or eliminating bacteria in the peri-implant pocket, resulting in reduced pocket depth and bleeding compared to mechanical debridement alone.8,12

When localized antimicrobial agents—such as chlorhexidine, tetracycline, doxycycline, and minocycline microspheres—are used as adjuncts with mechanical debridement, a greater decrease in pocket depth and bleeding is seen than with debridement alone.8,12,13 Roncati et al11 used a diode laser and a gel containing 0.2% chlorhexidine and 0.005% silver cations, in conjunction with mechanical debridement for nonsurgical therapy, on a patient with peri-implantitis. One year post-treatment, pocket depths were reduced from 9 mm to 3 mm, bleeding decreased, and improvement in bone levels were seen via radiography. Yet in another study, Jepsen et al3 reported that antimicrobials, local and systemic antibiotics, and air polishing did not reduce inflammation among implant patients.

Self-Care Recommendations

Properly educating patients on effective self-care strategies and patient compliance with the prescribed oral hygiene regimen are integral to the long-term success of implant therapy. This process begins prior to implant placement with a discussion of the meticulous self-care required and the importance of regular professional maintenance.1,2 Each patient needs an individualized plan for the natural teeth and/or implant prosthesis with verbal and visual demonstration of self-care aids that contour to the restoration.14

Self-care may include the use of a soft bristle manual or power toothbrush,15 small diameter end tuft brush to reach lingual or distal surfaces, interproximal brushes, water irrigators, APF-free fluoride toothpaste, and floss.1,2,12–14 Several floss products (woven, tape, threaders, etc) are available that will clean around or under implants.

Patients need verbal guidance and demonstration on how to floss around an implant to prevent floss impaction or shredding on a roughened implant abutment or prosthesis, as this can lead to a peri-mucosal infection.7,14 During the flossing instructions, the clinician should show the patient how to use a loop and crisscross (“shoe shine”) or c-shaped method. This prevents floss impaction and the creation of a roughened surface on the implant.

When using a water flosser, the patient should be instructed to aim the stream horizontally and not into the sulcus, which could damage the peri-implant seal.13 Antimicrobial agents—such as a chlorhexidine rinse for irrigation, chlorhexidine gel for interproximal brushing, essential oil mouthrinse, and toothpaste with 3% triclosan—are often recommended for at-home use.2,3,12 Patients should be on a short recare interval to assess plaque control, review self-care, and make changes as needed to maintain peri-implant health.

Conclusion

Although dental implants are the standard of care to replace missing dentition, recommendations on how implants should be maintained remain unclear. Evidence-based, consistent guidelines are important for all dental professionals—new and seasoned—to be competent in the care and maintenance of implants. For many patients, this is their last hope for maintaining their dentition. Future research can give answers to what is the most effective treatment and maintenance methods for long-term implant success.

References

- DuCoin FJ. Dental implant hygiene and maintenance: home and professional care. J Oral Implantol. 1996;22:72–75.

- Boyd LD, Mallonee LF, Wyche CJ, Halaris JF, eds. Wilkins’ Clinical Practice of the Dental Hygienist. 13th ed. Burlington, Massachusetts: Jones & Bartlett Learning LLC; 2020.

- Jepsen S, Berglundh T, Genco R, et al. Primary prevention of peri‐implantitis: Managing peri‐implant mucositis. J Clin Periodontol. 2015;42:S152–S157.

- Heitz-Mayfield LJA, Lang NP. Comparative biology of chronic and aggressive periodontitis vs. peri-implantitis. Periodontol 2000. 2010;53:167–81.

- Wingrove SS. Peri-implant Therapy for the Dental Hygienist: Clinical Guide to Maintenance and Disease Complications. Hoboken, New Jersey: Wiley-Blackwell; 2013.

- Costa FO, Takenaka‐Martinez S, Cota LOM, Ferreira SD, Silva GLM, Costa JE. Peri‐implant disease in subjects with and without preventive maintenance: a 5‐year follow‐up. J Clin Periodontol. 2012;39:173–181.

- Chen S, Darby I. Dental implants: maintenance, care and treatment of peri-implant infection. Aust Dent J. 2003;48:212–220.

- Renvert S, Polyzois I. Treatment of pathologic peri‐implant pockets. Periodontol 2000. 2018;76:180–190.

- Berglundh T, Armitage G, Araujo MG, et al. Peri‐implant diseases and conditions: Consensus report of workgroup 4 of the 2017 World Workshop on the Classification of Periodontal and Peri‐Implant Diseases and Conditions. J Clin Periodontol. 2018;45:S286–S291.

- Coli P, Sennerby L. Is peri-implant probing causing over-diagnosis and over-treatment of dental implants? J Clin Med. 2019;8:1123.

- Roncati M, Lauritano D, Tagliabue A, Tettamanti L. Nonsurgical periodontal management of iatrogenic peri-implantitis: a clinical report. J Biol Regul Homeost Agents. 2015;29(3 Suppl 1):164–169.

- Figuero E, Graziani F, Sanz I, Herrera D, Sanz M. Management of peri‐implant mucositis and peri‐implantitis. Periodontol 2000. 2014;66:255–273.

- Gulati M, Govila V, Anand V, Anand B. Implant maintenance: a clinical update. Int Sch Res Notices. 2014;2014:908534.

- Checchi V, Racca F, Bencivenni D, Lo Bianco L. Role of dental implant homecare in mucositis and peri-implantitis prevention: a literature overview. Open Dentistry Journal. 2019;13(1):470–477.

- Allocca G, Pudylyk D, Signorino F, Grossi G, Maiorana C. Effectiveness and compliance of an oscillating-rotating toothbrush in patients with dental implants: a randomized clinical trial. Int J Implant Dent. 2018;4:1–8.

From Dimensions of Dental Hygiene. May 2022;20(5):14-17.