Sunstar Spotlight: Providing Nutritional Guidance

Oral health professionals should be prepared to educate both patients and medical colleagues about the link between a healthy diet and oral health.

Introduction

Manager, Professional Relations Sunstar Americas Inc

The scope of practice for dental hygienists continues to expand, which brings added responsibility. Dental hygienists are charged with staying up-to-date on the most current research in dentistry and dental hygiene, as well as allied fields. Reviewing a patient’s health history can provide the information necessary to not only discuss patients’ oral health needs, but also their nutritional requirements. With more patients experiencing systemic health problems like diabetes, obesity, and celiac disease, the need for dental hygienists to provide dietary guidance is growing. In this month’s Sunstar Spotlight, Cynthia Stegeman, EdD, RDH, RD, CDE, a registered dietitian and certified diabetes educator, provides valuable insights to assist dental hygienists in providing nutrition recommendations to their patients.

Outside of demineralization and caries formation, many patients and health care providers do not realize the strong association that exists between nutrition and oral health. Dental hygienists are well positioned to educate both patients and medical colleagues about this link.

The Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics, the world’s largest organization of food and nutrition professionals, recently published a position paper, “Oral Health and Nutrition,” that provides guidance on oral health to nutrition professionals.1 The paper is written by Riva Touger-Decker, PhD, RD, FADA, of the University of Medicine & Dentistry of New Jersey-School of Health Related Professions and New Jersey Dental School in Newark, and Connie Mobley, PhD, RD, of the University of Nevada Las Vegas School of Dental Medicine. Several of the paper’s reviewers were dental hygienists, including: Jane McGinley, MBA, RDH, of the American Dental Association in Chicago; Lori A. Stockert, MS, RDH, of Pfizer Inc in Collegeville, Pennsylvania; and Rebecca Wilder, RDH, MS, of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill School of Dentistry.

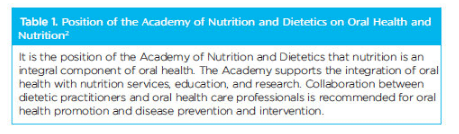

The strong role played by dental hygienists in this key dietetic paper speaks volumes for the need to create and maintain an interprofessional bond in order to enhance patient care. The oral health and nutrition position paper supports the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics’s statement on oral health (Table 1).2 As reported by the Accreditation Council for Education in Nutrition and Dietetics3 and supported by the position statement,2 an increase in education and training related to the connection between nutrition and oral health during dietetic education and post-graduate continuing education courses is necessary. As experts in the field, oral health professionals should serve as disseminators of dental health information.

The strong role played by dental hygienists in this key dietetic paper speaks volumes for the need to create and maintain an interprofessional bond in order to enhance patient care. The oral health and nutrition position paper supports the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics’s statement on oral health (Table 1).2 As reported by the Accreditation Council for Education in Nutrition and Dietetics3 and supported by the position statement,2 an increase in education and training related to the connection between nutrition and oral health during dietetic education and post-graduate continuing education courses is necessary. As experts in the field, oral health professionals should serve as disseminators of dental health information.

For oral health professionals, developing relationships with dietitians can be helpful in obtaining appropriate and current nutrition and diet information or requesting guidance regarding patients. Evaluating the literature on nutrition may be challenging, but it is the ethical responsibility of all oral health professionals to present information that is evidence-based. It is also within the dental hygiene scope of practice to provide nutrition screening/counseling as it pertains to oral health prevention and disease management. Going beyond this boundary requires a referral to a registered dietitian (RD), registered dietitian nutritionist (RDN), or medical provider.

![]() RESOURCES FOR ORAL HEALTH PROFESSIONALS

RESOURCES FOR ORAL HEALTH PROFESSIONALS

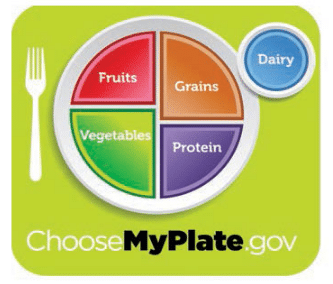

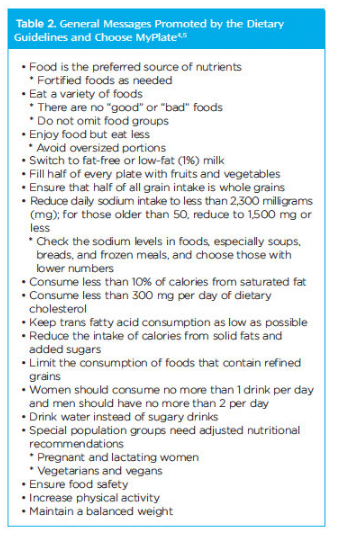

Dental hygienists need to be prepared to provide their patients with meaningful nutrition information, as well as prevent and correct any misconceptions about nutrition to improve both health literary and patient compliance with dietary recommendations. Two commonly used educational resources for delivering general nutrition advice and promoting healthy eating are the 2010 Dietary Guidelines for Americans4 and the coordinating Choose MyPlate,5 published by the United States Department of Agriculture and US Department of Health and Human Services. A recent survey of more than 500 RDs found that 75% preferred to use Choose MyPlate as a teaching tool when counseling individuals.6 Another survey, conducted by the International Food Information Council, found 61% of individuals were familiar with the visually pleasing Choose MyPlate icon (Figure 1).7 Both the Dietary Guidelines and Choose MyPlate provide direction for healthy individuals older than 2 who wish to minimize the risk of disease. Neither is intended to be used as a therapeutic diet or specific directive for managing dietary intake. Table 2 provides a listing of general messages offered by these two resources.

SUCCESSFULLY INTERPRETING NUTRITION RESOURCES AND RECOMMENDATIONS

Since the introduction of Choose MyPlate, several misconceptions have arisen. The easily recognizable Choose MyPlate symbol (Figure 1) is divided into four quadrants of food groups—protein, grains, vegetables, and fruits, with a serving of dairy on the side. Many health care professionals and patients interpret this as the need to eat something from each food group at each meal in the proportions indicated.8 This is not true. Rather, it is important to incorporate these healthy foods throughout the day and/or week. For example, a healthy dinner of baked chicken, broccoli, baked potato, salad with dressing, whole grain roll, and water (protein, grains, and vegetables) does not contain a dairy or fruit. Consuming a smoothie (fruit and yogurt, ie, dairy) or ice cream (dairy) with strawberries (fruit) as a snack in the evening is acceptable. Another example is a combination dish, such as macaroni and cheese (grain and dairy), that will not fit in two compartments. Along the same line, Choose MyPlate suggests that food should be consumed on a plate.8 Think of the situations when this is not practical: packed lunches for school or work; food from a drive-through restaurant; or chili in a bowl.

Because the Choose MyPlate symbol does not contain a “fat,” many people interpret this to mean a diet must be fat-free.8 Fat is an essential component to every diet and provides benefits such as energy, satiety, organ protection, and transportation of fat-soluble vitamins. The Dietary Guidelines recommend that 20% to 35% of the total calories consumed each day come from fat that is limited in cholesterol (less than 300 mg/day), saturated fat (less than 10%), and trans fat (less than 1%), while substituting with unsaturated fats.4 In addition, fat may have a cariostatic effect, as it may not be metabolized by microorganisms in plaque biofilm.9

A food group contained within Choose MyPlate is protein, which is often misinterpreted as “red meat.” Protein, however, is also found in numerous plant and animal sources, including meat, seafood, poultry, eggs, beans, peas, soy products, nuts, and seeds. Choose MyPlate recommends the inclusion of a variety of protein sources, as well as lean, low-fat, or fat-free choices.5 Protein is also considered cariostatic and does not lower plaque pH.9,*

Another aspect of Choose MyPlate that may require clarification is the misconception that no snacks are allowed.8 Some patients (eg, children, pregnant women, and women who are breastfeeding) may need snacks to receive adequate calories and nutrients. Oral health professionals realize the damage that frequent snacking can cause to oral health by reducing plaque pH and increasing the risk of demineralization. Recommending better snack options that are not cariogenic (eg, fresh fruit, cheese, raw vegetables and dip, yogurt, nuts), chewing gum with xylitol, or oral hygiene strategies following a snack are valuable suggestions.

Finally, one of the key messages of Choose MyPlate is “Make half your plate fruits and vegetables.”5 Dietetic professionals assert that the most important first step to improve overall health is to increase servings of fruit (1.5 cups to 2 cups/day with minimal juice) and vegetables (2 cups to 3 cups/day, including dark green, orange, and red vegetables).6,11 Dairy (3 cups/day) is the third food group most often identified as low, while grains (5 oz to 8 oz/day, making half whole grains) and protein (5 oz to 6.5 oz/day) tend to be higher than the recommendations.10,11 Dental hygienists, armed with this information, may quickly surmise goals for their patients.

APPLICATION OF NUTRITION PRINCIPLES—A CASE STUDY

Amanda is a 34-year-old mother of two boys, ages 12 and 6, who present to the dental office for 6-month recare appointments. At their previous appointments, the dental hygienist requested that Amanda bring in a 3-day food record for the children. Using the Choose MyPlate website, the dental hygienist identified the adequacy of each boy’s diet. In addition, she assessed the cariogenic potential of each food recorded. Overall, the dental hygienist found both diets to be inadequate in fruit, vegetable, and dairy consumption. She also discovered that the children experienced 2 hours of acid exposure each day due to soda intake and snack choices.

To address these concerns, the clinician spoke with Amanda about the need to ingest adequate nutrients in order for the children to develop oral soft and hard tissues, in addition to the concern about their increased caries risk. The dental hygienist provided general suggestions to increase nutrients and reduce cariogenic potential. Because the 6-year-old has type 1 diabetes, the dental hygienist referred Amanda to a RD/RDN. Later in the day, the dental hygienist called the RD/RDN to discuss the adverse dental implications of the child’s current diet. The RD/RDN will take the suggestions of the dental hygienist and modify the diabetes meal plan designed for the child. If the dental hygienist is also a certified diabetes educator (CDE), she may continue with the diet counseling. Dental professionals with a master’s degree or higher are now eligible to earn the CDE credential.12

The 12-year-old boy has full orthodontics. The dental hygienist educated both Amanda and the preteen on the need for nutrients to promote healthy periodontal ligaments and bone to encourage orthodontic tooth movement. Using the Dietary Guidelines and Choose MyPlate for handouts and direction, the dental hygienist offered recommendations for nutrient-dense foods, fruits, vegetables, and dairy, as well as snack ideas and alternatives to sodas. Discussion on sticky and hard foods, food retention, and food choices in relationship to orthodontic appliances completed the discussion.1,9

In speaking with Amanda, the dental hygienist found that she was recently diagnosed with celiac disease. The dental hygienist is unfamiliar with celiac disease and investigates, finding it to be an autoimmune disorder that causes the body to form antibodies to one’s own tissues. Amanda had an initial appointment with a RD/RDN for a gluten-free diet (omitting foods containing wheat, rye, and barley) and a follow-up appointment scheduled next month. She felt so much better after initiating the “gluten-free” diet that she told the dental hygienist she wanted to start making all meals gluten-free for her family. Feeling this was out of her scope of practice, the dental hygienist recommended that Amanda wait to apply the gluten-free principles for the rest of the family until she could consult with the RD/RDN. A gluten-free diet can be lower in fiber and nutrients. For individuals who do not need to omit foods containing gluten, this diet can exacerbate insulin resistance or glucose intolerance, cause weight gain, and deleteriously affect the health of the gut.9,13

In this private practice-based scenario, the dental hygienist played a vital role in educating the patient about the role of nutrition in her own and her family’s personal oral health and provided appropriate referrals.

CONCLUSION

Dental professionals must be knowledgeable and trained in providing evidence-based nutrition and diet information to patients in clinical and/or community dental settings as it relates to oral health. It is also pertinent to know when to collaborate interprofessionally to maintain optimal comprehensive dental care for all patients. The patient can be educated using two valuable nutrition tools published by the federal government: 2010 Dietary Guidelines for Americans and Choose MyPlate. An understanding of common areas of confusion related to Choose MyPlate may help dental professionals in providing clear and accurate nutrition and diet information. Nutrition and dentistry go hand-in-hand, and educating patients and providers is a step toward improving the health of the nation.

REFERENCES

- Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics. Practice Papers: Oral Health and Nutrition. Available at: eatright.org/members/practicepapers. Accessed June 16, 2014.

- Touger-Decker R1, Mobley C; Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics. Position of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics: oral health and nutrition. J Acad Nutr Diet. 2013;113:693–701.

- Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics. Accreditation Council for Education in Nutrition and Dietetics: 2012 Standards for Internship Programs in Nutrition and Dietetics. Available at: eatright.org/ACEND/content. aspx?id=787. Accessed June 16, 2014.

- United States Department of Agriculture; United States Department of Health and Human Services. Dietary Guidelines for Americans. 2010. Available at: health.gov/dietaryguidelines/dga2010/ DietaryGuidelines2010.pdf. Accessed June 16, 2014.

- United States Department of Agriculture. Choose MyPlate. Available at: choosemyplate.gov. Accessed June 16, 2014.

- Today’s Dietitian. 14 top diet trends for 2014: Annual survey of nutrition experts predicts the popular diet trends this New Year. Available at: prnewswire.com/news-releases/14-top-diet-trends-for-2014-237303161.html. Accessed June 16, 2014.

- International Food Information Council Foundation. 2013 Food and Health Survey: Consumer attitudes toward food safety, nutrition & health. Available at: foodinsight.org/foodandhealth2013.aspx. Accessed June 16, 2014.

- Haven J, Maniscalco S, Bard S, Ciampo M. MyPlate myths debunked. J Acad Nutr Diet. 2014;114:674–675.

- Stegeman CA, Davis JR. The Dental Hygienist’s Guide to Nutritional Care. 4th ed. St. Louis: Elsevier; 2015:415,370.

- Telgi RL, Yadav V, Telgi CR, Boppana N. In vivo dental plaque pH after consumption of dairy products. Gen Dent, 2013;61:56–59.

- United States Department of Agriculture and Economic Research Center. American diets are out of balance with dietary recommendations. Available at: ers.usda.gov/data-products/chartgallery/detail.aspx?chartId= 10487. Accessed June 16, 2014.

- National Certification Board for Diabetes Educators. Unique Qualifications Pathway. Available at: ncbde.org. Accessed June 16, 2014.

- Gaesser GA, Angadi SS. Gluten-free diet: Imprudent dietary advice for the general population? J Acad Nutr Diet. 2012;112:1330–1333.

From Dimensions of Dental Hygiene. July 2014;12(7):45–48.

RESOURCES FOR ORAL HEALTH PROFESSIONALS

RESOURCES FOR ORAL HEALTH PROFESSIONALS