Cranberry USA : Maintaining Skin Integrity

Clinicians need to take preventive action in order to preserve their hand health.

Hand hygiene is vital to preventing the spread of infections in both dental and medical settings.1 Effective and frequent hand washing and the continued donning and doffing of gloves are the cornerstones of hygiene protocol, but they can be harsh on the skin.2–4 As hands are washed frequently, the skin becomes damaged, which can lead to more frequent colonization of pathogenic microorganisms. Injured skin needs to be restored with emollients because the skin flora is altered, which results in an increased concentration of staphylococci and Gram-negative bacteria.5,6 As both medical and dental professionals are at increased risk of skin injury, they must remain up-to-date on strategies for maintaining skin integrity—from washing hands in warm water to increasing their use of alcohol-based hand rubs to choosing gloves coated with emollients and soothing ingredients.

SKIN ANATOMY

To better understand how detergents and other products affect skin, it is important to review basic skin anatomy. Human skin is made up of three layers: epidermis, dermis, and subcutaneous. The epidermis is composed of keratinocytes, which divide and move from the basal layer to the stratum corneum, the outer most layer of the skin (Figure 1). The stratum corneum protects the skin against microorganisms and foreign substances. The lipids in the stratum corneum provide hydration—helping skin maintain adequate moisture levels.

Water content is imperative to skin health. The softness and texture of the skin derive from the lipid and water concentration. Proper stratum corneum hydration improves skin barrier function.7 The depletion of water and lipid content leads to dry skin (Figure 2).8 Signs and symptoms of dry skin on the hands include irritation, irritant contact dermatitis, hand eczema, and allergic contact dermatitis, which can be visually seen on the palmar and dorsal sides of the hands, ?ngers, web spaces, and around the fingernails.9

TYPES OF HAND DERMATITIS

Hand dermatitis is a common problem among oral health care and medical providers. It is approximately 17% to 30% more common among medical and dental professionals than in the general population.10 Hand dermatitis is caused by exposure of skin to water, detergent, fragrances, antimicrobial agents, low humidity levels, frequent hand washing, and repeated gloving.2,10–14

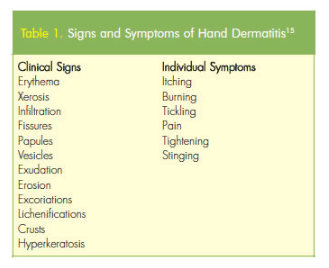

The two major types of skin irritation caused by hand hygiene include irritant contact dermatitis (Figure 3) and allergic contact dermatitis. Dryness, erythema, irritation, itching, and fissures are symptoms of irritant contact dermatitis (Table 1).15 Allergic contact dermatitis is rare and manifests as pruritic papules and vesicles on an erythematous base. It may range from mild to severe and localized to generalized. Patch testing, visual examination, and cultures are used to diagnose both types of dermatitis and rule out other causes.11

CONTRIBUTING FACTORS TO HAND DERMATITIS

While gloves help protect against the transmission of microorganisms, the prevalence of hand dermatitis increases with the frequency of glove changing.2,4,8,16,17 Wearing gloves intensifies the irritation experienced by individuals with hand dermatitis. The chemicals and accelerators used during glove manufacturing can lead to allergic contact dermatitis and wearing gloves for extended periods can cause the hands to sweat, causing irritation.18 The use of latex may exacerbate irritated skin and increase the risk of allergic reaction.18 Considering the skin health benefits of gloves is critical during selection, as there are many types available including nonlatex varieties and those with special additives to improve skin health.

Both oral health and medical professionals wash their hands over and over throughout the day, which raises the risk of hand dermatitis. Callahan et al19 studied the association between patch test response, season, and frequency of hand washing with hand dermatitis among 113 health care workers. Results showed individuals who washed their hands more than 10 times per day were 55% more likely to develop irritant contact dermatitis than those who washed less frequently. The time of year, or season, and dermatitis were also associated. The risk of developing dermatitis in cold, winter months was as much as three times greater than during warm months.19 Results further showed that individuals who were sensitive to sodium lauryl sulfate (SLS)—which is commonly found in personal care products, including soap—were at an increased risk of developing dermatitis.19

The use of alcohol-based hand rubs with emollients after hand washing may decrease hand dryness. These rubs are convenient and improve skin tolerance compared to hand washing.22,23 For maximum efficacy, an adequate amount of solution (at least 3 milliliters) must be rubbed vigorously over all hand surfaces for a minimum 10 seconds to 30 seconds until the solution has evaporated.22–24 Alcohol-based hand rubs with emollients should be only applied to dry hands and hands should not be washed immediately after application so the emollient quality of the rub is maintained.25

In a study conducted by Loffler and Kampf,20 participants were asked to wash one hand with soap containing SLS followed by the application of an 80% ethanol hand rub and cleanse the other hand with SLS detergent only. Results showed significantly more skin hydration on the hand washed with the combination of soap and alcohol-based hand rub. The authors suggest that the ethanol reduces the irritation caused by soap; however, when the order was changed to hand rub followed by hand wash, no difference in the reduction of irritation was observed.20

INCREASED RISK OF INFECTION

Hand hygiene is ineffective when skin integrity is compromised.4,14,26 The quantity and variety of microorganisms may increase when hand dermatitis is present because the stratum corneum on irritated hands is more vulnerable to microbial penetration.4,14,26 Borges et al2 evaluated changes in microflora caused by the use of gloves, soap, and antiseptics among health care workers with healthy and nonhealthy (evidence of dermatitis) hands after hand washing with nonmedicated soap for 30 seconds. Samples from participants’ dominant hands were collected and all subjects completed a hand skin assessment form, which recorded visual observations of redness, dryness, tingling, and scaling. Results from the self-assessment questionnaire revealed that participants believed gloves, soap, and alcohol contributed to their irritated hands. Microbial counts after hand washing were low in both groups; however, the number of microorganisms on healthy hands was significantly lower than on the nonhealthy hands.2

SIMPLE STRAGETIES FOR PREVENTION

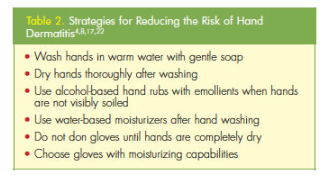

Hand washing and detergent use cause skin damage due to transepidermal water loss.21,27 In order to prevent hand dermatitis, clinicians should wash their hands in warm, not hot water; avoid irritants as much as possible; use emollients, such as lotions or creams to increase skin moisture; and choose gloves that support skin health.11,21,25,27 Table 2 provides a list of effective strategies for reducing the risk of hand dermatitis.4,11,15,25

Hand washing and detergent use cause skin damage due to transepidermal water loss.21,27 In order to prevent hand dermatitis, clinicians should wash their hands in warm, not hot water; avoid irritants as much as possible; use emollients, such as lotions or creams to increase skin moisture; and choose gloves that support skin health.11,21,25,27 Table 2 provides a list of effective strategies for reducing the risk of hand dermatitis.4,11,15,25

To help resolve contact dermatitis, regular application of hand lotions or ointments, especially after hand washing, is strongly recommended.9,27 Because oil-based moisturizers may contain ingredients that interfere with antimicrobials or compromise the integrity of gloves, water-based moisturizers should be used during the work day.25 Fragrance-free creams with few preservatives are recommended for irritated hands. While at home, clinicians should consider using a heavier, oil-based emollient to speed healing. Covering the hands with cotton gloves after application and wearing overnight may help improve skin health.25 Exposure to water should be reduced to support proper healing. Topical steroid treatment may also be prescribed by a dermatologist.9

Choosing the right gloves is also important to maintaining healthy skin. Some clinicians may be sensitive to latex proteins, so nitrile gloves are a better choice for these individuals. Gloves are now available that are coated with emollients, such as lanolin; antioxidants like vitamin E; and lubricants such as aloe, which may also be helpful. The next section of this supplement provides additional information about gloves with a lanolin/vitamin E coating.

CONCLUSION

Frequent hand washing and gloving are necessities in the safe provision of dental care. Because damaged skin is a reservoir for microorganisms and increases the likelihood of microbial transmission, clinicians must take preventive steps to reduce their risk of hand dermatitis. By incorporating these strategies into their daily routine, oral health professionals can improve their skin health and reduce their risk of exposure to dangerous pathogens.

Intact skin serves as the first line of defense for oral health professionals, who are at increased risk of hand dermatitis. But keeping the skin healthy can be a challenge for clinicians because of constant handwashing and the need to don and doff gloves throughout the day. According to the United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, hand dermatitis is one of the most prevalent types of occupational illness, with approximate costs surpassing $1 billion annually.1 In order to promote skin integrity, clinicians must take steps to ensure their skin retains moisture and to prevent dryness, which leads to dermatitis. To support oral health professionals in these endeavors, Cranberry has developed an innovative line of products that supports skin health, including gloves coated with a proprietary formulation of soothing lanolin and vitamin E.

LANOLIN AND VITAMIN E DEFINED

In order to prevent problems with skin health, Cranberry coats many of its gloves with the soothing and natural ingredients—lanolin and vitamin E. Lanolin is an additive that moisturizes and soothes skin while preventing dry, rough patches from forming in the first place. An amber-colored substance that is extracted from sheep’s wool after it is shorn but before it is washed, lanolin is composed of fatty acids and natural compounds (Figure 1). Lanolin is well known for its ability to soothe skin and is commonly used in personal care products, such as lotions, lip balms, and hair conditioners.

Lanolin is both an emollient, or skin softener, and a humectant—meaning it absorbs moisture from the air. Dry skin results from the absence of water in the top layer or epidermis of the skin. Emollients, such as lanolin, trap moisture in the epidermis to prevent skin from drying and reduce the risk of cracks forming in the skin.

Vitamin E refers to a group of fat-soluble compounds that provide anti oxidant properties. The topical application of this essential nutrient penetrates the epidermis and dermis layers of the skin. Essential to healthy skin, vitamin E provides a variety of anti-inflammatory benefits, including protection from free radicals and support of wound healing. Research also demonstrates that the topical application of vitamin E can improve skin moisture by boosting its ability to retain water.2,3

The addition of this powerful combination—lanolin and vitamin E—to gloves is de signed to significantly improve the skin of oral health professionals, which is almost always under attack. The lanolin creates a barrier on the skin’s surface to keep moisture in and prevent it from evaporating, while the vitamin E soothes angry skin and prevents additional damage. For clinicians who rotate between donning and removing gloves and frequent handwashing throughout the day, these potent additives can mean the difference between maintaining skin integrity and experiencing skin breakage.

RESULTS OF CLINICAL TESTING

The benefits of using gloves coated with lanolin and vitamin E are well documented. The Switzerland-based Skin Test Institute, which specializes in the in vivo testing of the efficacy and safety of products designed for the skin, compared Cranberry gloves with the lanolin/vitamin E coating to traditional clinical gloves on the following parameters: transepidermal water loss, skin moisture levels, skin peeling, and visible skin condition. The testing was conducted using three different tests. Trans epidermal water loss was measured with a Tewameter® (Figure 2), which uses a probe applied to the skin to measure humidity and temperature gradients. The transepidermal water loss is calculated based on the resultant humidity and temperature scores. A Corneo meter® was used to evaluate the skin’s hydration levels. The capacity of skin to retain moisture is determined by the dielectric constant of the water contained in the superficial layers of the stratum corneum, which is measured by the corneometer. The D-Squame Dry Skin Test® assessed skin dryness through test strips that increase visibility of adhering skin cells.

PROVEN RESULTS

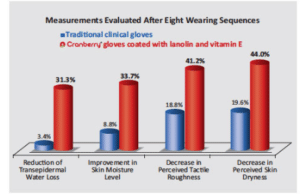

In an in vivo experiment comparing the efficacy of both types of gloves in reducing trans epidermal water loss, the gloves coated with lano lin and vitamin E decreased water loss by 31.3% after eight wearing sequences (about 6 hours of use) compared to the noncoated gloves, which reduced water loss by only 3.4% (Figure 3).

The gloves coated with lanolin and vitamin E also improved skin moisture levels more than traditional gloves. After four wearing sequences, the coated gloves already improved moisture levels by 22%, compared to 5.4% and, at eight wearing sequences, the coated gloves improved moisture levels by 33.7%, outperforming the traditional gloves, which only improved moisture levels by 8.8% (Figure 3).

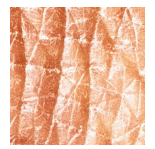

Individuals wearing traditional gloves experienced more severe symptoms of skin peeling compared to those using coated gloves. Wearing coated gloves reduced the amount of skin peeling by nearly 14%. The testing also observed the effects of wearing the coated gloves on the surface of the skin. Figure 4 shows the skin surface of a clinician with dry skin. The surface appears very rough and cracked. Cranberry’s coated gloves are designed to soothe the symptoms of dehydration and irritation, with the skin surface appearing smoother and softer in as little as 6 hours of wear (Figure 5). Study results also showed that the Cranberry’s coated gloves drastically reduced perceived skin roughness and dryness. Participants noted a 41.2% decrease in perceived skin roughness with the coated gloves compared to just 18.8% with traditional glove after eight wearing sequences (Figure 3).

Perceived dryness was also diminished by 44.0% among those wearing coated gloves vs 19.6% with traditional gloves after eight wearing sequences (Figure 3).

CRANBERRY’S SKIN HEALTH SERIES

As demonstrated by the testing results, gloves coated with lanolin and vitamin E help clinicians maintain their skin health and integrity. This proprietary formulation is only available with Cranberry gloves. From powder-free latex gloves to nitrile exam gloves, the benefits of this special coating can be found in the glove type preferred by individual clinicians. Cranberry’s most recent product launch is AQUA Source Nitrile Powder Free Exam Gloves, which offer the lanolin and vitamin E coating in addition to a comfortable fit, improved tactile sensitivity, and enhanced grip capabilities.

In addition to gloves, Cranberry also carries the S3 Series Face Mask line, many of which offer skin health benefits. Coatings of aloe vera, vitamin C, and vitamin E naturally moisturize and nourish the skin through the internal air circulation created by the natural breathing process. The masks also offer excellent breathability, secure protection, and a cool and lasting soft feeling without irritation.

See the ad on the last page for more details about Cranberry products. Clinicians can also review a complete catalog and request samples at cranberryusa.com. Special promotions and additional information appear on Cranberry’s Facebook page: face book.com/ cranberryusa.

References : Maintaining Skin Integrity

- Pittet D, Allegranzi B, Sax H, et al. Evidence-based model for hand transmission during patient care and the role of improved practices. Lancet Infect Dis. 2006;6:641–652.

- Borges Lizandra Ferreira de Almeida e, Silva BL, Gontijo Filho PP. Hand washing: changes in the skin flora. Am J Infect Control. 2007;35:417–420.

- Allegranzi B, Pittet D. Role of hand hygiene in healthcare-associated infection prevention. J Hosp Infect. 2009;73:305–315.

- Larson E, Girard R, Pessoa-Silva CL, Boyce J, Donaldson L, Pittet D. Skin reactions related to hand hygiene and selection of hand hygiene products. Am J Infect Control. 2006;34:627–635.

- Kampf G, Loffler H. Dermatological aspects of a successful introduction and continuation of alcohol-based hand rubs for hygienic hand disinfection. J Hosp Infect. 2003;55:1–7.

- Elsner P. Antimicrobials and the skin physiological and pathological flora. Curr Probl Dermatol. 2006;33:35–41.

- Guidelines on Hand Hygiene in Health Care. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2009.

- Kownatzki E. Hand hygiene and skin health. J Hosp Infect. 200355:239–245.

- Golden S, Tatyana S. Hand dermatitis: review of clinical features and treatment options. Seminars in Cutaneous Medicine and Surgery. 2013;32(3):147–157.

- Smit HA1, Burdorf A, Coenraads PJ. Prevalence of hand dermatitis in different occupations. Int J Epidemiol.1993;22:288–293.

- Abramovits W, Granowski P. Innovative management of severe hand dermatitis. Dermatol Clin. 2010;28:453–465.

- Stutz N, Becker D, Jappe U, et al. Nurses’ perceptions of the benefits and adverse effects of hand disinfection: alcohol-based hand rubs vs hygienic hand washing: a multicenter questionnaire study with additional patch testing by the German contact dermatitis research group. Br J Dermatol. 2009;160:565–572.

- Kampf G, Loffler H. Hand disinfection in hospitals—benefits and risks. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2010;8:978–983.

- Newman JL, Seitz JC. Intermittent use of an antimicrobial hand gel for reducing soap-induced irritation of health care personnel. Am J Infect Control. 1990;18:194–200.

- Kampf G, Loffler H. Prevention of irritant contact dermatitis among health care workers by using evidence-based hand hygiene practices: a review. Industrial Health. 2007;45:645–652.

- Occupational Safety and Health Administration. Medical and Dental Offices: A Guide to Compliance with OSHA Standards. OSHA 3187-09R, 2003. Available at:?7dds.org/uploads/knowledge_base/pdf/OSHA0001.pdf. Accessed June 16, 2014.

- Flyvholm M, Bach B, Rose M, Jepsen K, Frydendall JK. Self-reported hand eczema in a hospital population. Contact Dermatitis. 2007;57:110–115.

- Gallagher R1, Sunley K. Appropriate glove use in dermatitis prevention. Nurs Times. 2012;108:12–14.

- Callahan A, Baron E, Fekedulegn D, et al. Winter season, frequent hand washing, and irritant patch test reactions to detergents are associated with hand dermatitis in health care workers. Dermatitis. 2013; 24:170–175.

- Loffler H, Kampf G. Hand disinfection: How irritant are alcohols? J Hosp Infec. 2008;70:44–48.

- Kampf G, Kramer A. Epidemiologic background of hand hygiene and evaluation of the most important agents for scrubs and rubs. Clin Microbial Rev. 2004; 17:863–893.

- Picheansathian W. A systematic review on the effectiveness of alcohol-based solutions for hand hygiene. Int J Nurs Pract. 2004;10:3–9.

- Messina MJ, Brodell LA, Brodell RT, Mostwo EN. Hand hygiene in the dermatologist’s office: to wash or to rub? J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;59:1043–1049.

- Larson E. Analysis of alcohol-based hand sanitizer delivery systems: efficacy of foam, gel, and wipes against influenza A (H1N1) virus on hands. Am J Infect Control. 2012;40:806–809.

- Safety and Health Assessment and Research for Prevention (SHARP) Program, Washington Department of Labor and Industries. Hand Dermatitis in Health Care Workers. Available at: lni.wa.gov/Safety/Research/Dermatitis/files/derm_hcw.pdf. Accessed June 25, 2014.

- Rocha LA, Ferreira de Almeida E, Borges L, Gontijo Filho PP. Changes in hands microbiota associated with skin damage because of hand hygiene procedures on the health care workers. Am J Infect Control. 2009; 37:155–159.

- Williams C, Wilkinson SM, McShane P, et al. A double-blind, randomized study to assess the effectiveness of different moisturizers in preventing dermatitis induced by hand washing to simulate healthcare use. Br J Dermatol. 2010;162:1088–1092.

References : Strong in Protection, Soft on Skin

- United States Centers for Disease and Prevention. Skin Exposures and Effects. Available at: cdc.gov/niosh/topics/skin. Accessed June 25, 2014.

- Gehring W, Fluhr J, Gloor M. Influence of vitamin E acetate on stratum corneum hydration. Arzneimittelforschung. 1998;48:772–775.

- Gonullu U, Sensoy D, Uner M, Yener G, Altinkurt T. Comparing the moisturizing effects of ascorbic acid and calcium ascorbate against that of tocopherol in emulsions.J Cosmet Sci. 2006;57:465–473.

From Dimensions of Dental Hygiene. July 2014;12(7):19–25.