Stop the Cycle of Missed Appointments

Addressing the barriers many patients face when accessing dental care may help reduce the number of broken appointments.

This course was published in the September 2-15 issue and expires September 30, 2018. The author has no commercial conflicts of interest to disclose. This 2 credit hour self-study activity is electronically mediated.

EDUCATIONAL OBJECTIVES

After reading this course, the participant should be able to:

- Identify the effects of missed dental appointments on dental practices and health outcomes.

- Discuss the reasons behind broken appointments.

- Explain the relationship between dental anxiety and missed appointments.

Understanding the factors that contribute to broken appointments may help reduce their occurrence. These include a history of missed appointments, scheduling conflicts, poor patient management, insurance status, low socioeconomic status, race/ethnicity, language barriers, age, transportation problems, and psychosocial issues (cultural, linguistic, and emotional).3 This article will discuss the role access-to-care problems, cultural factors, and dental anxiety play in broken appointments and reduced patient cooperation.

ACCESS-TO-CARE PROBLEMS

Low-income populations experience high levels of dental diseases but underutilize oral health care services.4,5 A 2012 government survey found that low-income populations use dental services less than high-income populations. Hispanic populations also received dental care less often than their non-Hispanic counterparts.5 In a related medical study, the frequencies of missed or shortened treatments were highest among Hispanics and Native Americans.6

In May 2000, the Surgeon General released “Oral Health in America: A Report of the Surgeon General,” which addressed public perceptions regarding the current state of oral health in America and noted that few people consider oral signs and symptoms to be indications of general illness.7 As a result, the public may undervalue, avoid, or postpone needed care. This report highlighted the association between oral health and systemic health, and urged Americans to value their oral health. It also publicized the disparities faced by vulnerable populations in accessing oral health care.

Research also shows that low-income patients underutilize oral health care, regardless of whether they are uninsured or covered by Medicaid or the Children’s Health Insurance Program, which provides health insurance for 60 million low-income Americans.8,9 Complicating matters for Medicaid patients is the widely held misconception that this population breaks appointments frequently. As a result, many providers do not accept Medicaid patients even though current evidence contradicts this theory. For example, a study by Dobbs10 showed there was no statistically significant difference between Medicaid and nonMedicaid cohorts in regard to late and failed appointments. Dobbs also indicated that differences in broken appointments identified in Medicaid patients in earlier studies were more likely due to poor patient management. Despite the evidence, there continues to be a decline in dental provider participation in Medicaid, which further limits access to care for vulnerable groups.11

Another factor in the access-to-care equation is that health promotion policies and practices are not keeping up with the changing demographics of the US population. The makeup of the nation is more diverse than ever. Hispanics comprise the fastest growing minority in the US, making up approximately 17.4% of the population.12 As previously noted, this population experiences a high level of oral disease, as well as access-to-care problems. Patti R. Rose, MPH, EdD, a cultural competence scholar, refers to health disparity as a form of “health care inequality” or “gap” in the quality of health and health care across racial, ethnic, and socioeconomic groups.13 She suggests the disparities are mostly attributable to cultural health beliefs, lack of higher education, and linguistic incompetence. Uncovering the reasons for the disproportionate disease burden within the large Hispanic population—particularly cultural beliefs—may help shed light on the issues faced by other minority groups regarding the accessibility and utilization of health care.

IMPROVING CULTURAL COMPETENCE

Culture—a shared set of learned behaviors and beliefs—subtly defines the way its members communicate, think, and form ideas.13 Often, cultural beliefs supersede evidence or common knowledge and patients raised with a particular belief system regarding health and disease causation may experience negative health outcomes as a result. For instance, patients who associate dental visits with tooth loss may be less likely to seek and continue care and may not respond to traditional patient motivation methods.

Health and illness are often delineated and interpreted by people’s cultural beliefs.14 To illustrate, some Native Americans—particularly American Indians who continue to practice tribal religions and traditional medicine—believe their health is influenced by the quality of their interior life and their interactions with others and nature.15 Additionally, the Native American concept of treatment may be more dependent on the patient-healer relationship and the patient’s state of mind than on medicine. For example, in Native American health care, a shaman, medicine man, or doctor serves to alleviate ailments. These healers spend a lot of time with their patients, and achieving wellness often depends on a mutual understanding between the healer and the patient.16,17 Hence, patients whose health beliefs have a cultural basis may prefer seeking care from a provider with insight into what constitutes health and healing from their point of view. One size does not fit all, however, and even among communities of indigenous peoples, there are a multitude of differences that must be considered and explored during health counseling.17 Ideally, the provision of health care should be tailored to each patient’s unique circumstances and cultural perspective.

To reduce the gap in health disparity within ethnic populations (populations with shared cultural traits), the group’s sense of community and health needs to be recognized, validated, and respected. Clinicians need to be culturally sensitive to such beliefs. Lack of cultural competence may interfere with patients understanding the importance of the treatments recommended, leading to cancelations and broken appointments.

Linguistic factors are also a factor in broken or missed appointments, as language barriers can adversely affect the delivery of health care services in multilingual communities.13 Individuals who are not proficient in the English language may have difficulty understanding written materials, the need for follow-up, and medication requirements. Laveist18 reports that non-English speaking Hispanic patients use health care services less than members of other ethnic or racial groups. These results were consistent with previous studies that found an association between the lack of English fluency and a reduction in health care utilization.

Sociologists refer to acculturation as the psychological process of change that occurs when two distinct cultures come into continuous contact.19 This process occurs during immigration to a new geographical location. Large numbers of the Hispanic community have deep ties to their culture and face challenges balancing their cultural identity with that of the dominant American culture. Understanding contextual factors regarding the adaptation process for acculturating populations may help improve patient/provider relationships.19

These limitations of acculturation result in fractionalization from the host country that impact health and well-being. For example, a study found that Mexican-Americans with low acculturation status between the ages of 12 and 50 had significantly higher mean numbers of decayed teeth than those with high acculturation status.20 Results from this study underscore the possible correlation between the limited acculturation process in the Mexican-American community and evidence of high debris and calculus indices and the presence of decay, gingivitis, and periodontitis.20

The impetus behind cultural competence in dental accreditation standards is to develop oral health providers who are able to communicate effectively with individuals, groups, and other health care providers and to recognize the cultural influences impacting the delivery of health services.21 Culturally competent practitioners maintain recognition of and respect for individual values, attitudes, and behaviors, and find ways to mitigate the health consequences of complete adherence to a culture of origin. The provision of culturally competent care accommodates the increasingly diverse patient population and serves all patients well by eliminating disparities in the processes and outcomes of care.

ADDRESSING DENTAL ANXIETY

Approximately 40% of the adult population experiences dental-related fear and anxiety, which are the leading causes of dental treatment avoidance, missed appointments, long recare intervals, incomplete or interrupted treatment plans, and absence of continuing oral health care.22,23 Rayman et al24 defines dental fear as “an unpleasant mental, emotional, or physiologic sensation derived from a specific dental-related stimulus that can lead to dental anxiety, or a nonspecific unease, apprehensive, or negative thoughts about what may happen during an oral health care appointment.” The presence of dental fear and anxiety may have negative consequences for oral and systemic health. Clinicians need to understand the cause or stressors behind patient fears in order to effectively manage them.

Often, fear originates from a traumatic dental experience during childhood. Thomson25 notes that 50% to 80% of individuals experiencing dental-related fear and anxiety reported struggling with symptoms during their childhood or adolescence. Porritt et al26 suggest that dental fear may be hereditary, or initiated via parental influence. Hence, fearful or anxious children usually have fearful or anxious parents. Research has shown that dental anxiety during childhood develops as a result of direct experience and parental modeling.26 Additionally, adults with anxiety tend to exhibit more intense symptoms while in the dental chair. Patients with anxiety and dental fear often avoid necessary oral health care and neglect oral hygiene, consequently raising their risk of oral and periodontal diseases.26 If left unchecked, this damaging cycle of behaviors (passed on from one generation to the next) becomes firmly entrenched with negative consequences for health care adherence.

To provide a more patient-centered approach to care, dental professionals need to assess each patient’s dental anxiety before treatment and manage each case according to his or her individual needs. Therefore, it is important to screen for potentially anxious or fearful patients as part of a risk management process that identifies those at high risk for oral diseases.

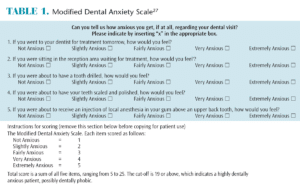

Anxious patients should be asked to complete a dental anxiety questionnaire, such as the Modified Dental Anxiety Scale (Table 1), as part of their complete medical histories.27 Ideally, this questionnaire should be taken before the first dental appointment to determine the origins and levels of dental anxiety. Also, the earlier dental professionals determine the presence or levels of fear and anxiety, the greater the likelihood for successful out-comes.28 The answers to such a questionnaire may provide: the stimuli that causes fear, such as smells/sounds/sights common to the dental environment; the level of anxiety experienced; and guidance on appropriate management practices.

Implementing changes, such as avoiding typical dental odors, reducing the noise level in the operatory with headphones, and providing pleasant visual scenery, may relieve anxieties associated with the dental environment. The “tell, show, do” approach that includes constant communication regarding treatment plan implementation builds trust and enables patients to feel a sense of control and empowerment while receiving dental care.

Another approach, systematic desensitization, incrementally exposes the patient to fearful stimuli while providing relaxation strategies, such as constant reassurance and information.29,30 Providing rest breaks throughout the appointment and instructing patients to signal if they need a break builds trust and instills confidence in patients. In a study by Corah et al,30 the use of distractive stimuli such as musical programs reduced dental anxiety. The utilization of guided imagery may help patients mentally transport to a more peaceful and relaxing environment. Additionally, encouraging paced or rhythmic breathing lessens the autonomic “fight or flight” response associated with anxious patients.28,30 If these strategies are not successful, working with the patient’s physician and psychologist to provide additional strategies may help. Anxious patients who are in a lot of pain may require treatment under sedation.26

CONCLUSION

Clinicians willing to explore, understand, and manage factors that increase patients’ risk of noncompliance may improve cooperation and care outcomes. Similarly, patients who understand the relationship between missed appointments and their health may adhere to treatment recommendations.28,31

Patient cooperation in maintaining recare recommendations is key to successful care. It directly impacts treatment planning, continuity of care, practice management, and outcomes. Frequent appointment cancellations are symptoms of a break in patient cooperation. Humanistic approaches to managing broken appointments include respecting all patients’ dignity and worth.32 Broken appointments should be addressed through meticulous assessment and personalized patient-centered care. Understanding the cultural, linguistic, and psychological barriers faced by patients who frequently break appointments may help clinicians initiate effective management plans to address this significant problem.

REFERENCES

- Mckenzie S. Curbing cancellations and no-shows begins Chair-side. Available at: dentaltribune.com/articles/specialities/practice_man agement/816_curbing_cancellations_and_noshows_ begins_chairside.html. Accessed August 25, 2015.

- Almog DM, Devries JA, Borrelli JA, Kopycka- Kedzierawski DT. The reduction of broken appointment rates through an automated appointment confirmation system. J Dent Educ. 2003;67:1016–1022.

- Samuels RC, Ward VL, Melvin P, et al. Missed appointments: factors contributing to high no-show rates in an urban pediatrics primary care clinic. Clin Pediatr (Phila). 2015;54:976–982.

- Manski RJ, Madger LS. Demographic and socioeconomic predictors of dental care utilization. J Am Dent Assoc. 1998:129:195–200.

- Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Dental Services—Mean Median Expenses per Person with Expense and Distribution of Expenses by Source of Payment: United States, 2011. Available at: meps.ahrq.gov/ mepsweb/ data_stats/ tables_ compendia_ hh_interactive.jsp. Accessed August 25, 2015.

- Obialo C, Zager PG, Myers OB, Hunt WC. Relationships of clinic size, geographic region, and race/ethnicity to the frequency of missed/shortened dialysis treatment. J Nephrol. 2014;4:425–430.

- Oral Health in America: A Report of the Surgeon General. Rockville, Maryland: US Department of Health and Human Services; 2000.

- Alexander LL, LaRosa JH, Bader H, Garfield S. New Dimensions in Women’s Health. Sudbury, Massachusetts: Jones and Bartlett Publishers; 2010.

- Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Medicaid Eligibility. Available at: medicaid.gov/ medicaid-chip-program-information/bytopics/ eligibility/eligibility.html. Accessed August 25, 2015.

- Dobbs ME, Manasse R, Kusnoto B, Costa Viana MG, Obrez A. A comparison of compliance in Medicaid versus non-Medicaid patients. Spec Care Dentist. 2015;35:56–62.

- Horsly BP et al. Appointment Keeping Behavior of Medicaid Versus Non-Medicaid Orthodontic Patients. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthopedics. 2007;132:49–53.

- Pew Research Center. Factank, News in the Numbers. Hispanic Population Reaches Record 55 Million. Available at: pewresearch.org/facttank/ 2015/06/25/u-s-hispanic-population-growthsurge- cools. Accessed August 25, 2015.

- Rose PR. Cultural competency: understanding cultural nuances and barriers to cultural appreciation. In: Competency for Health Administration and Public Health. Miami: Jones and Bartlett; 2011.

- Spector RE. Cultural Diversity in Health and Illness. 7th ed. Upper Saddle River, New Jersey: Pearson Prentice Hall; 2009.

- Garrett MT, Portman TAA. Native American healing traditions. International Journal of Disability, Development and Education. 2006;53(4):453–469.

- American Cancer Society. Making Treatment Decisions: Native American Healing. Available at: cancer.org/docroot/ETO/content/ETO_5_3X_Native_A merican_Healing.asp? sitearea=ETD. Accessed August 25, 2015.

- Lee CC, ed. Multicultural Issues in Counseling: New Approaches to Diversity. 4th ed. Hoboken, New Jersey: Wiley and Sons; 2014.

- LaVeist T. Disentangling race and socioeconomic status: a key to understanding health inequalities. J Urban Health. 2005; 82(2 Suppl 3):26–34.

- Berry JW. Psychology of Acculturation. Lincoln, Nebraska: University of Nebraska Press; 1990.

- Ismali AI, Szpunar SM. Oral health status of Mexican-Americans with low and high acculturation status: findings from Southwestern HHANES, 1982- 84. J Public Health Dent. 1990;50:24–31.

- Accreditation Standards for Dental Education Programs from the Commission on Dental Accreditation. Chicago: American Dental Association; 2010.

- Kvale G, Berggren U, Milgrom P. Dental fear in adults: a meta-analysis of behavior interventions. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2004;32:250–264.

- Daniel SJ, Harfst SA, Wilder RS. Mosby’s Dental Hygiene Concepts, Cases and Competencies. 2nd ed. St. Louis: Mosby; 2008:758–761.

- Rayman S, Dincer E, Almas K. Managing dental fear and anxiety. N Y State Dent J. 2013:79:25–29.

- Thomson WM, Locker D, Poulton R. Incidence of dental anxiety in young adults in relation to dental treatment experiences. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2000;2:8289–8294.

- Porritt J, Mashman Z, Rodd HD. Understanding children’s dental anxiety and psychological approaches to its reduction. Int J Pediatric Dent. 2012;22:397–405.

- Humphris GM, Morrison T, Lindsay SJ. The Modified Dental Anxiety Scale: validation and United Kingdom norms. Community Dent Health. 1995;12:143–150.

- Armfield JM, Heaton, LJ. Management of fear and anxiety in the dental clinic: a review. Aust Dent J. 2013;58:390–407.

- Benson H, Greenwood MM, Klemchuk H. The relaxation response: psychophysiologic aspects and clinical applications. Int J Psychiatry Med. 1975;6:87–98.

- Corah NL, Gale EN, Pace LF, Seyrek SK. Relaxation and musical programming as means of reducing psychological stress during dental procedures. J Am Dent Assoc. 1981;103:232–234.

- Paterson BL, Charlton P, Richard S. Nonattendance in chronic disease clinics: a matter of noncompliance? Journal of Nursing and Healthcare of Chronic Illness. 2010:2(1):63–74.

- Kemp F. Alternatives: A review of nonpharmacologic approaches to increasing the cooperation of patients with special needs to inherently unpleasant dental procedures. The Behavior Analyst Today. 2005;6(2):92.

From Dimensions of Dental Hygiene. September 2015;13(9):60–63.