Saving Lives with Early Detection

The critical role of the dental hygienist in decreasing the morbidity and mortality associated with oral cancer.

This course was published in the September 2009 issue and expires September 2012. The authors have no commercial conflicts of interest to disclose. This 2 credit hour self-study activity is electronically mediated.

EDUCATIONAL OBJECTIVES

After reading this course, the participant should be able to:

- Define oral squamous cell carcinoma.

- Discuss the incidence of oral squamous cell carcinoma and how it changes in response to gender and ethnicity.

- Discuss the possible causes of oral squamous cell carcinoma.

- Understand how to recognize precancerous lesions.

Dental hygienists are on the front lines of oral cancer detection. A comprehensive intraoral and extraoral cancer screening should be performed at least once a year on all patients seen in the dental operatory. Dental hygienists play a critical role in this process because they often spend the most time with patients.

WHAT IS ORAL CANCER?

Oral squamous cell carcinoma is a malignant neoplasm of the oral cavity that derives from stratified squamous epithelium. The term malignant neoplasm is defined as “an abnormal mass of tissue, the growth of which exceeds and is uncoordinated with that of the normal tissues and persists in the same manner after cessation of the stimuli which evoked the change.”2 Malignant neoplasms arise from a sequential accumulation of genetic alterations in the tissue. They result in excessive and uncoordinated growth as well as the ability to infiltrate other tissues and/or metastasize.

THE INCIDENCE OF ORAL SQUAMOUS CELL CARCINOMA

Oral squamous cell carcinoma, which arises from the oral mucosal surface, is by far the most common type of oral cancer, accounting for more than 90% of cases.1,3 Worldwide, more than 500,000 new oral cancer cases are diagnosed annually, with 29,370 cases occurring in the United States.4-6 Oral/pharyngeal cancer represents approximately 3% of all cancer cases in the United States—ranking as the sixth most common cancer among men and the twelfth most common among women.3 The disparity in incidence rates between men and women has become less pronounced over the past half century because the use of alcohol and tobacco in women has increased.4,7 The incidence is also higher among African American men.3

Each year, oral cancer claims the lives of approximately 7,320 Americans.4 Despite advances in radiation and chemotherapy, the 5- year survival rate has not improved significantly over the past few decades.7 Overall, only about 59% of people who are diagnosed with oral cancer will survive longer than 5 years after the initial diagnosis.4 The 5-year survival rate for African Americans is only 34%.1 Race appears to be an influential factor, likely due to genetic predisposition and/or socio-economic factors such as reduced access to health care, lack of awareness of the condition, and lower incidence of early diagnosis.1

For oral cancer patients who survive the treatment, their quality of life is severely affected because of complications from the highly aggressive therapy.1 Because oral cancer is often diagnosed late, therapy may be ineffective.1 Therefore, the stage at which oral cancer is diagnosed is critical to make an accurate prognosis. Oral cancer that is diagnosed at an early stage has a significantly more favorable prognosis compared to identifying the disease when it has become an advanced lesion. Also, there is usually less treatment morbidity associated with early lesions compared to treatment morbidity for oral cancer that is discovered at an advanced stage.

ETIOLOGY OF ORAL CANCER

The exact cause of oral cancer has eluded investigators for decades. Many factors may play a role in malignant transformation.8 See Table 1 for a list of risk factors.9

The strong association between squamous cell carcinoma of the oral cavity and tobacco use is well established. Studies show that smoking has a positive correlation with the prevalence of oral squamous cell carcinoma. The risk of developing a malignancy is also dose dependent— the more a person is exposed to tobacco, the greater his or her risk of developing oral cancer.10 Some studies quote the risk of developing oral cancer to be five to nine times greater for smokers than for nonsmokers. For extremely heavy smokers who smoke 80 or more cigarettes per day, the risk of oral cancer may grow to 17 times higher than for nonsmokers.7 Duration of tobacco use also has a significant impact on the risk of cancer development.10 The risk of a second primary carcinoma of the upper aerodigestive tract varies between 10% and 30% among those diagnosed with oral cancer, and it is higher among smokers.1

Research shows that the risk of a negative prognosis is two to six times greater among patients receiving treatment for oral cancer who continue to smoke than those who quit after the initial diagnosis.7 Chemotherapy may be less effective for oral cancer patients who continue to smoke.11 Evidence suggesting that tobacco smoke has an influence on gene expression and cellular pathways may explain why chemotherapy is less effective for smokers.11 Smokers and nonsmokers who have undergone radiation therapy are also at an increased risk of developing other forms of cancer because of the ionizing form of this treatment.

Excessive alcohol use is another major risk factor for upper aerodigestive tract cancers. In studies that have been controlled for smoking, moderate to heavy drinkers are three to nine times more likely to develop oral cancer than those who do not consume alcohol. Tobacco use synergizes with heavy alcohol use in a dose dependent manner and the overall effect is multiplicative.12

THE ROLE OF THE HUMAN PAPILLOMAVIRUS

Recent evidence also suggests that the human papillomavirus (HPV) is related to oropharyngeal cancers.7 The virus has the ability to integrate into the host’s genetic material and inhibits the host from regulating the normal proliferation process of an infected cell. HPV 16 and 18 have been identified in up to half of all oropharyngeal cancers but in a lesser proportion of intraoral cancers and those involving the tongue.13,14 In addition, systemic conditions such as iron deficiency— especially the severe chronic type— is associated with an elevated risk for squamous cell carcinoma of the oropharynx and posterior mouth. Patients who have Plummer- Vinson or Paterson-Kelly syndrome are at an increased risk of developing oral cancer at a younger age than patients who have iron deficiency alone. Plummer-Vinson syndrome— also called Paterson-Kelly syndrome—is caused by long-term iron deficiency and results in difficulty swallowing due to esophageal webs (small, thin growths of tissue that partially block the esophagus).3,15

Immunosupression may also play a role in the development of oral malignancies. The suppression of the immune system may increase the risk of carcinogenesis in many ways—it may facilitate infection with oncogenic viruses or it may allow the growth of genetically abnormal cells that would normally be controlled by a healthy immune system.16 Individuals who have acquired immunodeficiency syndrome and/or those undergoing immunosuppressive therapy for an organ transplant are at an increased risk of oral squamous cell carcinoma and other malignancies of the head and neck.3

PREMALIGNANT LESIONS OF THE ORAL CAVITY

A precancerous lesion is defined as “morphologically altered tissue in which cancer is more likely to occur than its apparently normal counterpart.”17 Many cases of oral cancer are preceded by premalignant lesions. However, the proportion of squamous cell carcinomas that develop through clinically recognizable precancerous stages is not known. The most important predictor of malignant transformation is the presence of epithelial dysplasia.18,19 Epithelial dysplasia is a disorganized growth of epithelium and abnormal morphologic changes that can be seen at the cellular level. Microscopic evaluation of the epithelium adjacent to oral squamous cell carcinoma often reveals dysplastic changes that are frequently multicentric.20 Epithelial dysplasia is categorized as mild, moderate, or severe.21 Overall, the proportion of dysplastic epithelial lesions that evolve into cancer is about 16%19 and the time period over which this occurs may be up to and beyond 20 years.22 A higher grade of dysplasia is generally associated with an increased risk of carcinoma.21 Only 4% to 11% of mild to moderate dysplasia cases progress to squamous cell carcinoma, whereas 35% of lesions diagnosed as severe dysplasia progress to squamous cell carcinoma.3,19 Therefore, severe dysplasia has a very high risk of subsequent development into cancer when compared to mild or moderate dysplasia.23 However, the presence of dysplasia does not always predict the development of squamous cell carcinoma, which may also develop in the absence of dysplasia.24

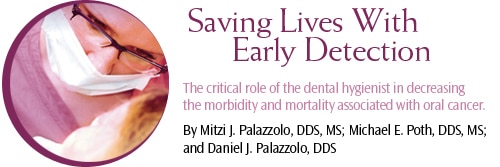

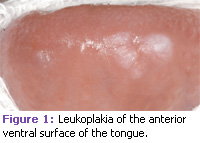

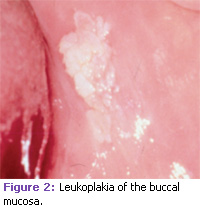

Clinically, precancerous lesions often present as either white or red patches known as leukoplakia and erythroplakia, respectively. These lesions cannot be removed by scraping. Oral leukoplakia is a clinical term defined by the World Health Organization as “a white patch or plaque that cannot be characterized clinically or pathologically as any other disease.”7,17 See Figures 1, 2, and 3. Leukoplakia may occur either as a single, localized lesion of the oral mucosa, as multiple lesions, or as widespread, often diffusely outlined lesions.

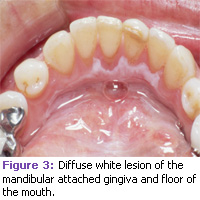

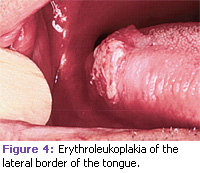

Most white patches of the oral cavity are benign in nature and often represent hyperkeratosis due to trauma. However, when a lesion fails to resolve in a period of 2 weeks after removal of a possible causative agent, a biopsy is mandatory to aid in establishing a definitive diagnosis. Erythroplakia is a red patch that cannot be removed by scraping and must be differentiated from other specific or nonspecific inflammatory oral lesions. In most cases, this can only be accomplished by performing a biopsy. A variation of leukoplakia, known as “speckled leukoplakia” or “erythroleukoplakia” presents clinically as a white patch with scattered areas of redness (see Figure 4). Lesions with this appearance have been associated with a greater frequency of epithelial dysplasia or carcinoma.20

In various studies, 15.6% to 39.2% of leukoplakia biopsy samples demonstrate epithelial dysplasia or invasive carcinoma,7 and more than one-third of oral carcinoma specimens have areas of leukoplakia in close proximity.7,22 White or red colored lesions that are located in the floor of the mouth are particularly worrisome because of the frequency of carcinoma at this site (42.9%). Oral cancer can affect any area of the oral cavity. However, the ventral surface of the tongue, lateral border of the tongue, and floor of the mouth are the most common locations. Dental hygienists must be vigilant in identifying and referring patients who present with these lesions. Timely assessment and treatment can significantly increase the chance for patient survival.

CLINICAL IMPLICATIONS FOR DENTAL HYGIENISTS

The most important approach to decreasing morbidity and mortality associated with oral cancer is to increase early detection. The hope of identifying lesions early is that they will be easier to treat. The most important component is to identify the typical risk factors that are associated with oral cancer and provide counseling to prevent use and encourage cessation of tobacco products and/or consumption of excessive amounts of alcohol. Professional and public education regarding oropharyngeal cancer has much room for improvement. Clinicians must perform routine oral cancer examinations to promote early diagnosis and treatment.

REFERENCES

- Silverman S Jr. Demographics and occurrence of oral and pharyngeal cancers. The outcomes, the trends, the challenge. J Am Dent Assoc. 2001;132(Suppl):7S-11S.

- Willis R. The Spread of Tumors In the Human Body. London: Butterworth & Co; 1952.

- Neville B, Damm D, Allen C, Bouquot J. Oral and Maxillofacial Pathology. 2nd ed. Philadelphia: W.B. Saunders; 2002.

- American Cancer Society. Cancer Facts and Figures 2005. Available at: www.cancer.org/docroot/STT/content/STT_1x_Cancer_Facts__Figures_2005.asp. Accessed August 14, 2009.

- Sanderson RJ, Ironside JA. Squamous cell carcinomas of the head and neck. BMJ. 2002;325:822-827.

- Vokes EE, Weichselbaum RR, Lippman SM, Hong WK. Head and neck cancer. N Engl J Med. 1993;328:184-194.

- Neville BW, Day TA. Oral cancer and precancerous lesions. CA Cancer J Clin. 2002;52:195-215.

- Binnie WH, Rankin KV, Mackenzie IC. Etiology of oral squamous cell carcinoma. J Oral Pathol. 1983;12:11-29.

- Ibsen Olga AC. The missing link. Dimensions of Dental Hygiene. 2008;6(11):22-26.

- Strycharz M, Polz-Dacewicz M, Gotlabek W, Swietlicki M, Kupisz K. [Tobacco smoking as a risk factor for oral cancer.] Przegl Lek. 2008;65:446-450.

- Gumus ZH, Du B, Kacker A, et al. Effects of tobacco smoke on gene expression and cellular pathways in a cellular model of oral leukoplakia. Cancer Prev Res (Phila Pa). 2008;1:100-111.

- Johnson NW. [Aetiology and risk factors for oral cancer, with special reference to tobacco and alcohol use.] Magy Onkol. 2001;45:115-122.

- Kreimer AR, Clifford GM, Boyle P, Franceschi S. Human papillomavirus types in head and neck squamous cell carcinomas worldwide: a systematic review. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2005;14:467-475.

- Paz IB, Cook N, Odom-Maryon T, Xie Y, Wilczynski SP. Human papillomavirus (HPV) in head and neck cancer. An association of HPV 16 with squamous cell carcinoma of Waldeyer’s tonsillar ring. Cancer. 1997;79:595.

- Santoro E, Gambardella P, Piscicelli I. [On the Plummer-Vinson syndrome with precancerous lesions of the tongue.] Rass Int Clin Ter. 1970;50:753-761.

- Demarosi F, Lodi G, Carrassi A, Soligo D, Sardella A. Oral malignancies following HSCT: graft versus host disease and other risk factors. Oral Oncol. 2005;41:865-877.

- Axell T, Pindborg JJ, Smith CJ, van der Waal I. Oral white lesions with special reference to precancerous and tobacco-related lesions: conclusions of an international symposium held in Uppsala, Sweden, May 18-21 1994. International Collaborative Group on Oral White Lesions. J Oral Pathol Med. 1996;25:49-54.

- Scully C, Cawson RC. [Potentially malignant lesions]. K Epidemiol Biostat. 1996;1:3-12.

- Lumerman H, Freedman P, Kerpel S. Oral epithelial dysplasia and the development of invasive squamous cell carcinoma. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 1995;79:321-329.

- Bouquot JE, Ephros H. Erythroplakia: the dangerous red mucosa. Pract Periodontics Aesthet Dent. 1995;7:59-67.

- MacDonald D, Saka SM. Structural Indicators of the High Risk Lesion. Cambridge, United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press; 1991.

- Silverman S Jr, Gorsky M, Lozada F. Oral leukoplakia and malignant transformation. A follow-up study of 257 patients. Cancer. 1984;53:563-568.

- Krogh P, Holmstrup P, Vedtofte P, Pindborg JJ. Yeast organisms associated with human oral leukoplakia. Acta Derm Venereol Suppl (Stockh). 1986;121:51-55.

- Karabulut A, Reibel J, Therkildsen MH, Praetorius F, Nielsen HW, Dabelsteen E. Observer variability in the histologic assessment of oral premalignant lesions. J Oral Pathol Med. 1995;24:198-200.

From Dimensions of Dental Hygiene. September 2009; 7(9): 56-59.