SSHEPARD/ ISTOCK/ ISTOCK

SSHEPARD/ ISTOCK/ ISTOCK

Reporting Notifiable Infectious Diseases

Oral health professionals need to understand the process for reporting such conditions at the local, state, and national levels.

When health care professionals, researchers, and the general public are looking for health-related information—such as disease prevalence, signs and symptoms of diseases or disorders, and methods of treatment and prevention—the United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) offers a wealth of resources on its website: cdc.gov. It is frequently the main source of accurate and updated information on health and disease in the US. To provide the public with these data, the CDC must collect and analyze information from a network of local and state health departments.

Fast and accurate data sharing and reporting are essential in cases of infectious diseases that can quickly spiral into epidemics and pandemics. This article examines the process of infectious disease information gathering by local and state health departments and the CDC; the difference between “notifiable” and “reportable” diseases and conditions; types of notifications required and examples of specific notifiable infectious diseases; and rationale for under-reporting or nonreporting of infectious diseases.

NOTIFIABLE INFECTIOUS DISEASES/CONDITIONS

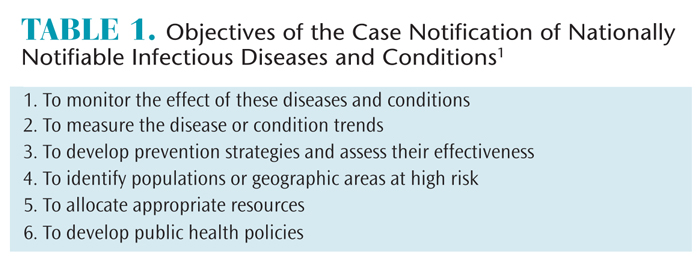

A notifiable infectious disease or condition necessitates regular, frequent, and timely information about individual cases of this disease in order to prevent and control it.1 The list of nationally notifiable infectious diseases and conditions is periodically revised based on the emergence of new pathogens. For example, the Zika virus and congenital infection were recently added to this list as the epidemic progressed and cases were identified in the US.2 A disease can also be removed from the list if its incidence declines. The list of nationally notifiable diseases is developed collaboratively by the Council of State and Territorial Epidemiologists (CSTE), local and state health departments, and the CDC. Table 1 lists the objectives of the case notification of nationally notifiable infectious diseases and conditions.1

The CDC has been responsible for the collection of data on nationally notifiable diseases and conditions since 1961.1 Beginning in 1990, the data that were previously reported to the CDC as cumulative counts were captured electronically as individual cases without personal identifiers. In 2001, the National Electronic Disease Surveillance System (NEDSS) was established to improve the accuracy, completeness, and timeliness of reporting at the local, state, territorial, and national levels. A major advantage of the NEDSS is its ability to capture health information contained within electronic forms, such as laboratory test results needed for case confirmation. All 50 state health departments are using NEDSS-compatible systems to transmit their data to the CDC, making the process quick, accurate, and efficient.1

National surveillance data are compiled by the CDC from case notification reports of the nationally notifiable infectious diseases and conditions submitted by the 57 reporting jurisdictions including 50 state, five territorial, and New York City and District of Columbia health departments. Because each jurisdiction is subject to appropriate legislation, regulations, and rules, reportable conditions in each jurisdiction may differ. Some infectious diseases designated as nationally notifiable by the CSTE might not be included in the list of reportable diseases by the local or state jurisdiction.1 This variability between states can make data aggregation difficult or impossible, and results in a fragmented national surveillance approach.2 In 2005, approximately 128 CDC-assigned codes for reportable diseases were in place—or just over one-third of the 373 diseases reportable in at least one jurisdiction, presenting a substantial barrier to the reporting process.3 The increasing use of electronic medical records should help improve this situation.

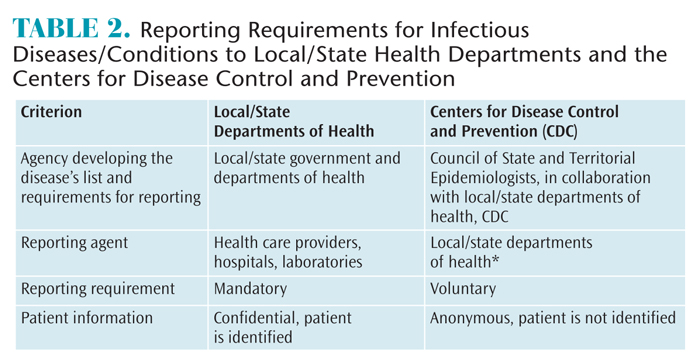

An important distinction between reporting an infectious disease to local/territorial/state health departments and their subsequent notification of the CDC is that the former is mandated and the latter is voluntary.1 This means that health care providers, hospitals, and laboratories are required to report cases to their appropriate departments of health. The information identifies the patient but is confidential. Proper identification (ensuring confidentiality according to the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act) is necessary at the local and state levels to ensure adequate protection of public health by providing treatment to those already ill; tracing contacts who might need vaccines, treatment, quarantine, or education; enabling the necessary investigation to stop disease outbreaks; eliminating environmental hazards; and closing premises where disease transmission may be ongoing.1 In contrast, the information reported to the CDC doesn’t include the patient’s identification. Only age, sex, and location are included in the report, in addition to the disease/condition; case status (confirmed, probable, or suspected); and the earliest event date (exposure or disease onset, diagnosis date, laboratory test or result date, or the date of report to the public health system).4 Table 2 summarizes the main differences between infectious diseases/conditions reportable to local/state health departments and nationally notifiable diseases/conditions reported to the CDC.

An important distinction between reporting an infectious disease to local/territorial/state health departments and their subsequent notification of the CDC is that the former is mandated and the latter is voluntary.1 This means that health care providers, hospitals, and laboratories are required to report cases to their appropriate departments of health. The information identifies the patient but is confidential. Proper identification (ensuring confidentiality according to the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act) is necessary at the local and state levels to ensure adequate protection of public health by providing treatment to those already ill; tracing contacts who might need vaccines, treatment, quarantine, or education; enabling the necessary investigation to stop disease outbreaks; eliminating environmental hazards; and closing premises where disease transmission may be ongoing.1 In contrast, the information reported to the CDC doesn’t include the patient’s identification. Only age, sex, and location are included in the report, in addition to the disease/condition; case status (confirmed, probable, or suspected); and the earliest event date (exposure or disease onset, diagnosis date, laboratory test or result date, or the date of report to the public health system).4 Table 2 summarizes the main differences between infectious diseases/conditions reportable to local/state health departments and nationally notifiable diseases/conditions reported to the CDC.

TYPES OF NOTIFICATIONS

Depending on the nature of the infectious agent, the danger to the public, and the likelihood that it will develop into an epidemic, nationally notifiable infectious diseases are noted as extremely urgent, urgent, and standard when reporting to the CDC.4,5 According to the stage in infectious disease diagnosis, the cases are classified as suspected, probable, and confirmed. The infectious agent and the possibility of its intentional release determine the following notification:

- All cases prior to classification, such as possible bioterrorism or especially dangerous infectious agents (eg, anthrax, botulism, plague, tularemia, severe acute respiratory syndrome [SARS], diphtheria, Haemophilus influenzae, tetanus, and trichinellosis)

- Confirmed, probable, or suspect cases (eg, Lyme disease, malaria)

- Confirmed and probable cases (eg, chronic hepatitis B, hepatitis C, mumps, and salmonellosis) must be reported to the CDC according to their urgency classification

- Only confirmed cases (eg, cholera, rubella, rabies, and measles) must be reported to the CDC according to their urgency classification5

To report an infectious disease case that requires extremely urgent notification, representatives of public health agencies must call the CDC Emergency Operations Center at 770-448-7100 within 4 hours and submit an electronic case notification report the next business day.4,5 The CDC strongly encourages early communication, which should not be delayed if information is not yet verified or missing.4 The CDC official will follow up on the extremely urgent notification within 1 hour. In some situations, clinicians call the CDC directly, bypassing their local or state departments of health, to notify it of the infectious disease on the immediately notifiable list. In such cases, the CDC immediately informs the local or state department of health.4 As of January 1, 2016, infectious diseases that require extremely urgent notification are anthrax, botulism, plague, paralytic poliomyelitis, SARS, smallpox, tularemia, and viral hemorrhagic fever.5

For infectious disease cases that require urgent notification, a representative of the public agency must call the CDC within 24 hours of receiving reports of such cases. The CDC will return such calls within 4 hours. Again, information must also be sent to the CDC electronically the next business day.4,5 Brucellosis, diphtheria, initial detection of novel influenza A virus infections, measles, nonparalytic poliovirus infection, rabies, rubella, and yellow fever are infectious diseases that require urgent notification.5

INFECTION CONTROL CONSIDERATIONS6,7

All patients should be treated as though they have an infectious disease. As such, patients with diagnosed infectious conditions do not need special accommodations. Rather, universal precautions must be implemented when treating all patients. Following are a few strategies for the safe treatment of patients.

- Follow the United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s (CDC) Guidelines for Infection Control in Dental Health-Care Settings—2003; the CDC’s recently published Summary of Infection Prevention Practices in Dental Settings: Basic Expectations for Safe Care; and the Occupational Safety and Health Administration’s Bloodborne Pathogens Standard.

- Prevent occupational exposure to blood through the use of intraoral fulcrums and sharp instruments to ensure stability during scaling and root planing; donning personal protective equipment such as masks, gloves, eyewear, and a protective garment; limiting the use of fingers for retracting tissue; and implementing devices such as instrument cassettes and recap needles to avoid sharps injuries.

- Keep all immunizations up to date.

- Ensure the office has an exposure control plan.

- Remain up to date on infection control standards. The CDC and the Organization for Safety, Asepsis and Prevention (OSAP) are excellent resources.

All other nationally notifiable infectious diseases and conditions require standard notification. Diseases in this category are also known as routinely notifiable and include foodborne disease outbreaks; hepatitis A, B, and C; human immunodeficiency (HIV) infection; mumps; and tuberculosis.5 Standard notifications do not require a phone call to the CDC, but they must be submitted electronically within the next weekly reporting cycle.5,8 The following examples of nationally notifiable infectious diseases and conditions were selected due to the Zika virus epidemic and the presence of disease signs in the oral cavity and head/neck area (HIV infection/acquired immune deficiency syndrome [AIDS] and mumps).

The following examples of nationally notifiable infectious diseases and conditions were selected due to the Zika virus epidemic and the presence of disease signs in the oral cavity and head/neck area (HIV infection/acquired immune deficiency syndrome [AIDS] and mumps).

ZIKA VIRUS

Complete and up-to-date information about the emerging Zika virus epidemic is available on the CDC website. It includes disease statistics, geography, transmission, signs and symptoms, complications, association with microcephaly and birth defects, and methods of disease prevention.9 Information for health care providers is also provided, such as resources for clinical guidance, clinical evaluation, diagnostic testing, and special populations, including pregnant women and patients with comorbidities such as HIV. As a currently developing epidemic, Zika virus infection was not included in the list of the nationally notifiable conditions approved by the CSTE in June 2015,5 but it was added in February 2016 as a routinely notifiable condition with standard reporting timeline.10 The CSTE recommended that territories and states enact laws and regulations to make Zika disease reportable in their jurisdictions. Health care providers are encouraged to report suspected cases of Zika infection to the local/state departments of health, which can notify the CDC after the infection is confirmed by laboratory testing.10

Because patients with active Zika disease are unlikely to seek routine dental and dental hygiene treatment, the role of oral health professionals may be limited to conducting thorough medical history and travel history where appropriate, referring when applicable, and providing information about the disease and its prevention.11 If Zika virus infection is suspected, the patient should be referred to his or her primary care provider for further assessment and for diagnostic testing at a laboratory capable of conducting such testing.10

HUMAN IMMUNODEFICIENCY VIRUS/ ACQUIRED IMMUNE DEFICIENCY SYNDROME

The first cases of HIV infection and AIDS (stage 3 HIV infection) were reported in 1981. Advances in diagnostic testing since then have led to several revisions to the surveillance case definitions.1,12 By April 2008, all 57 reporting jurisdictions in the US introduced laws and regulations that required confidential name-based reporting for HIV infection and AIDS, which must be confirmed by laboratory testing.1 The latest HIV surveillance case definition was published by the CDC in 2014 and is intended for monitoring the HIV infection burden and planning for prevention and care on a population level.12 The local/state departments of health notify the CDC of the confirmed cases of HIV infection according to the standard timelines for reporting as described.5

Between 30% and 80% of patients with HIV infection have oral lesions including oral candidiasis, oral hairy leukoplakia, Kaposi sarcoma, oral warts, herpes simplex virus ulcers, major aphthous ulcers or ulcers not otherwise specified, HIV salivary gland disease, xerostomia, and atypical gingival and periodontal diseases.13,14 Identifying these oral manifestations in patients in a dental setting can aid in detecting a previously unknown HIV infection. Thus, oral health professionals may be the first health care providers to increase patients’ awareness and refer them for medical consultation and testing. Additionally, many patients already diagnosed with HIV infection are treated with antiretroviral therapies that have adverse oral effects, including salivary gland disease, xerostomia, and human papillomavirus-related lesions.13

Research shows that patients15 and primary care physicians16 view chairside screening in dental settings favorably, and oral health professionals consider such screenings important and are willing to incorporate them into practice.17 Additionally, as oral HIV rapid testing has become available, it may be well suited for dental settings, although the feasibility of such testing should be further investigated prior to implementation.18

MUMPS

Mumps is an acute communicable viral disease. Since 1967, its incidence in the US has decreased about 99% following the introduction of a vaccination.19 There are occasional outbreaks of the disease, especially in the winter-spring seasons and in close-contact settings, such as educational facilities and dormitories. As of June 6, 2016, 1,272 cases of the disease have been diagnosed this year.19 An outbreak among students at Harvard University in April 2016 caused alarm.20 Mumps is a nationally notifiable infectious disease and its confirmed and probable cases are reported to the CDC by the local/state departments of health according to the standard notification timelines.5

Oral health professionals should be familiar with the signs and symptoms of mumps, as there is typically a bilateral involvement of parotid salivary glands (pain, swelling, tenderness). In about 25% of mumps cases, the involvement is unilateral and less frequently submandibular and sublingual, as well (10%). Therefore, this infectious disease may be initially found in dental settings. Other, nonspecific signs of mumps include fever, headache, and malaise, and the disease can be mild or asymptomatic.21 However, the possible complications are serious, such as viral meningitis, sensorineural hearing loss, and orchitis in men, which can, rarely, cause sterility.21,22 A two-dose measles, mumps, and rubella (MMR) vaccination introduced in 1989 is 91% to 94.5% effective, although there is evidence of reduced immunity over time.22 In addition to suspecting the disease and making an appropriate referral, oral health professionals may play an important role in providing information to patients about the importance of vaccinations against mumps and other infectious diseases, as well as vaccine effectiveness and safety.

BARRIERS TO EFFECTIVE REPORTING

The public health surveillance system relies on the timely, accurate, and complete reporting of notifiable infectious diseases to the local and state departments of health followed by notification to the CDC, according to the established guidelines. This is especially important if the infectious disease is acute, severe, and highly transmissible; has the potential to develop into an outbreak or epidemic; and poses a substantial danger to the public.8 Timely national data collected from multiple reporting jurisdictions may be used for identifying multi-state disease outbreaks, enabling the federal public health system to help states in the prevention and control measures. However, due to the hierarchical structure of reporting, delays at each level of reporting contribute to notification delays at the national level.3,8

Other factors present additional barriers to efficient reporting. Local and state jurisdictions vary in their reporting requirements and in their consensus of which infectious diseases are considered reportable, and a uniform information model is lacking.3,8 In order to be effective reporters, health care providers must be familiar with what diseases and conditions require reporting, maintain an understanding of the case reporting criteria, and know how to submit a report if necessary. There are often minimal rewards for reporting or punitive consequences for nonreporting.3 An earlier investigation found that information for health care providers about reportable conditions was provided on all local/state department of health websites, but often it was not prominently displayed.3However, a simple web search for “reportable infectious diseases ______ state” will most likely provide a link to the information. If health care providers are not familiar with the reporting requirements in their states, this may be the simplest approach.

CONCLUSION

Oral health professionals may play a vital role in recognizing infectious diseases, including those that require reporting to local and state public health authorities and the CDC. Appropriate referral to a primary care physician or hospital is a necessary step. Some communicable infectious diseases, however, do not need to be confirmed and should be reported as soon as possible if they are suspected or probable. Therefore, to prevent an outbreak of infectious disease and to ensure the fastest response by the public health system, oral health professionals should be familiar with the infectious disease reporting requirements in their state/local jurisdictions and know where to find pertinent information and resources.

References

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Summary of notifiable infectious diseases and conditions—United States, 2013. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2015;62:1–124.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. National Notifiable Diseases Surveillance System. 2016 Nationally Notifiable Infectious Diseases. Available at: cdc.gov/nndss/conditions/notifiable/2016. Accessed August 29, 2016.

- Doyle TJ, Ma H, Groseclose SL, Hopkins RS. PHSkb: A knowledge base to support notifiable disease surveillance. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak. 2005;5:27.

- Council of State and Territorial Epidemiologists. Surveillance/Informatics Committee. Process statement for Immediately Nationally Notifiable Conditions. Available at: cdc.gov/nndss/document/09-SI-04.pdf. Accessed August 29, 2016.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Protocol for Public Health Agencies to Notify CDC About the Occurrence of Nationally Notifiable Conditions. Available at: cdc.gov/nndss/document/NNC-2016-Notification- Requirements-By-Condition.pdf. Accessed August 29, 2016.

- Garland K. How do I best protect myself? Dimensions of Dental Hygiene’s Ask the Expert online forum. Available at: dimensionsofdentalhygiene.com/ asktheexpert/blog.aspx?id=18536&blogid=7259&term=universal%20precaut ions. Accessed August 29, 2016.

- Garland K. Will I contract an infectious disease from a patient? Dimensions of Dental Hygiene’s Ask the Expert online forum. Available at: dimensionsofdentalhygiene.com/asktheexpert/blog.aspx?id=20599&bid=725 9&blogid=7259&term=universal%20precautions. Accessed August 29, 2016.

- Jajosky RA, Groseclose SL. Evaluation of reporting timeliness of public health surveillance systems for infectious diseases. BMC Public Health. 2004;4:1.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Zika Virus. Available at: cdc.gov/zika/index.html. Accessed August 29, 2016.

- Council of State and Territorial Epidemiologists. Notice to Readers: Changes in the Presentation of Zika Virus Disease, Non-Congenital Infection, and Addition of Zika Virus Congenital Infection to Notifiable Diseases and Mortality Table I. Available at: cdc.gov/mmwr/volumes/65/wr/ mm6520a6.htm. Accessed August 29, 2016.

- Matthews A, Cohen Brown G. Preparing for the Zika virus. Dimensions of Dental Hygiene. 2016;14(6):48–51.

- Selik RM, Mokotoff ED, Branson B, Owen SM, Whitmore S, Hall HI. Revised surveillance case definition for HIV infection—United States, 2014. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2014;63:1–10.

- Cohen Brown G. Oral Lesions and Treatment Recommendations for the HIV-Infected Patient. CME and dental-accredited self-study module. Albany Medical College and NY/NJ AIDS Education & Training Center; 2010.

- Patton L. Oral lesions associated with human immunodeficiency virus disease. Dent Clin North Am. 2013;57:673–698.

- Greenberg BL, Kantor ML, Jiang SS, Glick M. Patients’ attitudes toward screening for medical conditions in a dental setting. J Public Health Dent. 2012;72:28–35.

- Greenberg BL, Thomas PA, Glick M, Kantor ML. Physicians’ attitudes toward medical screening in a dental setting. J Public Health Dent. 2015;75:225–233.

- Greenberg BL, Glick M, Frantsve-Hawley J, Kantor ML. Dentists’ attitudes toward chairside screening for medical conditions. J Am Dent Assoc. 2010;141:52–62.

- Pollack HA, Pereyra M, Parish CL, et al. Dentists’ willingness to provide expanded HIV screening in oral health care settings: results from a nationally representative survey. Am J Public Health. 2014;104:872–880.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Mumps: Cases and Outbreaks. Available at: cdc.gov/mumps/outbreaks.html. Accessed August 29, 2016.

- Sabate I. Mumps count rises to 40, concerning HUHS director. Available at: thecrimson.com/article/2016/4/26/mumps-concerns-HUHS-director/. Accessed August 29, 2016.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Mumps for Healthcare Providers. Available at: cdc.gov/mumps/hcp.html. Accessed August 29, 2016.

- Dayan GH, Rubin S, Plotkin S. Mumps outbreaks in vaccinated populations: are available mumps vaccines effective enough to prevent outbreaks? Clin Infect Dis. 2008;47:1458–1467.

From Dimensions of Dental Hygiene. September 2016;14(09):34, 36, 38-40.