ANTONIO_DIAZ/ISTOCK/GETTY IMAGES PLUS

ANTONIO_DIAZ/ISTOCK/GETTY IMAGES PLUS

Reaching Beyond the Operatory

Dental hygienists are well-equipped to advocate for improving access to care for the Nation’s most vulnerable populations.

This course was published in the January 2021 issue and expires January 2024. The authors have no commercial conflicts of interest to disclose. This 2 credit hour self-study activity is electronically mediated.

EDUCATIONAL OBJECTIVES

After reading this course, the participant should be able to:

- Identify those populations with the most unmet dental needs.

- Discuss the role of increasing licensure portability, expanding scope of practice for dental hygienists, instituting reimbursement reform, and using midlevel practitioners in improving access to care.

- Explain how dental hygienists can advocate for improved access to oral healthcare among vulnerable populations.

Despite advancements in prevention and health promotion programs, oral diseases and oral health disparities remain significant problems among vulnerable communities in the United States.1,2 Vulnerable populations include low-income individuals, ethnic and racial minorities, children, older adults, people experiencing homelessness, incarcerated individuals, those with disabilities or chronic medical conditions, and socially marginalized groups.3 Health disparities are defined as significant differences in health linked to social and economic disadvantages.4 Health obstacles faced by vulnerable populations include race and ethnicity, education, socioeconomic status, geographic location, insurance coverage, gender, age, sexual orientation or gender identity, health literacy, and disability status. These barriers are major public health problems in the US.3,4

The commitment to equitable access to care is a fundamental ethical principle of all healthcare professionals.5–8 Healthcare professionals, such as dental hygienists, play a vital role in advocating for health equity including access to oral health care and equitable distribution of healthcare resources.1,2,9 The purpose of this paper is to raise critical awareness about oral health disparities, promote new dental hygiene workforce models, and improve access to oral care through basic advocacy efforts.

UNMET DENTAL NEEDS

Vulnerable populations face greater barriers to accessing oral care such as unequal distribution of dental resources and living in health professional shortage areas (HPSAs).1,2 More than 59 million Americans live in HPSAs, which results in about a third of this population experiencing unmet dental needs.10 Limited access to care and the connection between oral health and overall health significantly impact the ability to lead a healthy life.1,2 Dental caries is the most common and frequently neglected health condition, affecting 90% of those ages 20 to 64 and 50.5% percent of children ages 6 to 11.11–13 Mexican American and non-Hispanic Black individuals and children of low socioeconomic status have the highest caries rate and prevalence of untreated decay compared to non-Hispanic white and nonpoor children.12 Additionally, periodontal diseases affect 42% of those age 30 and older and nearly 70.1% of those between the ages of 65 and 74.14 Both dental caries and periodontal diseases are preventable and treatable in their early stages; however, health and healthcare disparities—such as unequal access to preventive oral care and treatment—affect vulnerable populations. Severe consequences of poor oral health and untreated dental caries and periodontal diseases include pain, impaired function, and serious infections.2,3 Poor oral health is also associated with diabetes, cardiovascular disease, and other systemic diseases.15

The growing prevalence of oral diseases among vulnerable populations poses a significant economic burden to the US healthcare system.1,16 Even though the US has seen a decrease in emergency department (ED) visits for untreated dental conditions, $1.6 billion was spent on ED dental care in 2012.17 In a more recent study on dental-related hospital ED visits, 30% were by adults covered by Medicaid and more than 40% were uninsured.16 Oral diseases also exert indirect costs such as lost work productivity and negative impact on employment.2,3 Approximately 320.8 million hours of lost work productivity and missed school hours are due to untreated oral diseases and oral care visits for treatment in adults.18 For children, untreated oral diseases can cause pain, inability to learn, lack of concentration, and absence from school, resulting in 34.4 million school hours lost each year due to unplanned dental care.19 Quality oral health is vital to a productive and healthy life.

BEYOND BORDERS

The elimination of oral health disparities is a public health need, and broadening the scope of practice for dental hygienists may be part of the solution.4 In some states, dental hygienists have direct access to patients, practice independently, work in public health, or are in collaborative practice. These clinicians can initiate patient treatment based on assessment and dental hygiene diagnosis without the supervision of a dentist.20 These new dental hygiene workforce models may decrease oral disease burden. Research using a Dental Hygiene Professional Practice Index has suggested a broader dental hygiene scope of practice positively and significantly impacted oral health outcomes by increased use of oral health services and decreased tooth removal due to decay or disease.14

Dental hygiene license portability—the ability of dental hygienists to practice across state lines without needing to take additional regulatory exams—is another possible solution.21–23 This is similar to the nurse licensure compact, an interstate agreement allowing registered nurses to practice outside their licensed state without having to obtain another license.24 Similarly, the Task Force on Assessment of Readiness has asked state dental boards to allow increased dental licensure portability.25 As of today, Arizona allows for license portability and Oregon is accepting dental/dental hygiene test results and board examinations from other states for licensure.22,26 Another recent example of licensure portability is the redeployment of the healthcare workforce during the COVID-19 pandemic. This was accomplished through the loosening of traditional scope of practice and licensing boundaries, resulting in the increased ability of healthcare teams to meet the challenges of testing and treating patients while not compromising either the quality or safety of patients. This same flexibility in dental hygiene might improve the availability of dental services. Working together with health coalitions, professional associations, and state dental boards to improve dental hygiene license portability is one way to increase access to care.

REIMBURSEMENT REFORM

The majority of oral healthcare (86%) is financed by private sources such as employment-based dental insurance benefits or out-of-pocket payments by patients.27 Private insurance reimbursement rates average about 80.5% for children’s dental services and 78.6% for adult dental services. Medicaid fee-for-service reimbursement rates average 49.4% for children’s and 37.2% for adult dental services.28 This lack of reimbursement further contributes to health disparities because dental coverage is mostly limited to children, reimbursement rates are too low to sustain a dental practice, and bureaucratic barriers for enrollment and services are burdensome.1,3,29 Increasing Medicaid reimbursement rates to 75% and reducing administrative burdens can incentivize dental provider participation and patient use of services.29 Dental hygienists should stay abreast of current Medicaid reimbursement policies, as 18 states currently allow direct Medicaid reimbursement for dental hygienists.30 Dental hygienists can use their experience in treating vulnerable populations to communicate with Medicaid officials about proposed payment reforms and regulatory systems.

NEW SYSTEM OF CARE

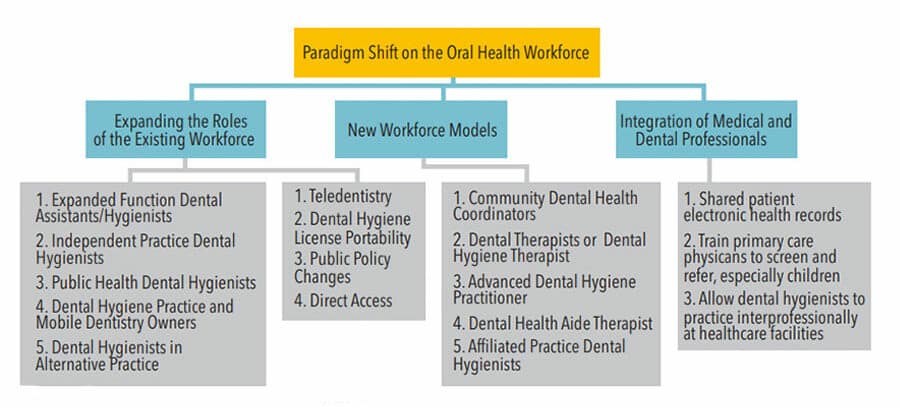

The current dental and dental hygiene workforce is incapable of meeting the public’s oral health needs.31 Licensure of midlevel practitioners, such as dental therapists and advanced dental hygiene practitioners, can improve access to care for high-risk populations.9,16,31 Dental therapists work in underserved communities in a collaborative agreement with dentists, providing routine preventive and restorative care, including restorations and simple extractions.32 Research suggests that dental therapy increases access to care for underserved populations, including reducing the rate of untreated decay.23 Expanding the scope of practice and authorizing licensure of mid-level dental hygiene providers create a new oral health workforce that can increase access to care and improve oral health.16 Successful implementation of new workforce models (Figure 1) requires obtaining support from oral health coalitions and other healthcare professions, development of new educational curricula, and reform of the Medicaid payment system, such as reimbursement in nontraditional settings, higher reimbursement rates, and simpler provider enrollment processes.22

ADVOCATING FOR ACCESS

Available at: create.piktochart.com/output/48325476-advocacy-infograph

Promoting access to oral healthcare is a fundamental ethical principle of the American Dental Hygienists’ Association (ADHA).7 Dental hygienists can advocate for better health outcomes and improvement of access to care because they have an intimate understanding of oral health needs and are experts in their field.9 Advocacy can positively influence access to care and public health policy such as the expansion of the dental hygiene scope of practice.9,33 There are basic steps that all dental hygienists can use to initiate advocacy and create change.

Implementing an advocacy plan requires an understanding of individual legislative and health policy systems as each state varies in established policy processes for legislation.34 Before initiating support for a legislative change or implementing new legislation, the following steps should be followed:

- Gather evidence-based research

- Implement advocacy resources

- Develop a strategic plan

- Create an evidence-based fact sheet

- Contact state legislators

Figure 2 provides an advocacy action infograph with links to resources.

Legislative preparation can be as simple as learning about the legislative process, state legislative procedures, and voting history of state senators and representatives.34–37 State websites provide information about legislative and budget processes as well as contact information for state legislators and the governor’s office. Also, legislative staff members are available to help answer questions and provide information about state legislation. Start small by choosing to advocate for a community issue, a bill in legislation, a change to the practice act such as dental hygienists administering the flu vaccine, or investigate the ADHA current advocacy efforts for ideas.38

Once the legislative process has been reviewed, information should be gathered from reputable and evidence-based resources for discussions with policymakers, other healthcare professionals, academic professionals, public health officials, advocacy groups, and stakeholders. Evidence-based research lends credibility to advocacy efforts and will aid in impacting change. Professional associations, such as the ADHA and the American Dental Education Association, provide advocacy resources and information helpful for navigating the legislative arena.38,39 National organizations such as the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention offer evidence-based published research resources.40 Advocacy groups and professional associations are vital as they may already be doing the groundwork for policy change and pursuing legislation for access to care. Seeking mentors within the dental hygiene profession and through advocacy partnerships provides opportunities for interprofessional collaboration to sustain advocacy efforts to create change.41

Implementing a strategic plan is vital for identifying legislative supporters, strengths, and weaknesses of the legislation, as well as opportunities and threats that might be presented during the process.42,43 Actions can include meeting as a component; discussing advocacy issues, ideas, and solutions; gathering data from resources; and drafting letters to state legislators. When writing a letter, sharing stories about the reality in your community can be an effective strategy to raise awareness about access to care or other legislative issues.

Initial and continued contact with state legislators via email, phone, letter, or face-to-face contact is crucial for presenting reasons why legislation is needed.42 An arranged personal visit will provide a greater impact. A key point to remember when presenting information is to be respectful and limit material to 1 page. A fact sheet is an excellent way to present multiple sources of evidence-based literature with a letter.42 Legislative advocacy efforts require commitment, time, relationship building, and persistence.43–46

CONCLUSION

Reducing oral health disparities means providing vulnerable populations with equitable access to quality oral healthcare. Expanding the scope of practice for dental hygienists and midlevel practitioners will help to improve access to care for vulnerable and underserved communities. Dental hygienists must inform policymakers on local, state, and federal levels about the results of dental hygiene health research, implementation of effective public health interventions programs, and population health in order to create change. Ultimately, reducing health inequalities requires the shared support of the next generation of dental hygienists. Educating the dental hygiene community on its role as advocates and mentoring dental hygienists in advocacy efforts are essential to addressing public health concerns such as access to care.

REFERENCES

- United States Office of the Surgeon General. National Call To Action To Promote Oral Health. Rockville, Maryland: National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research: 2003.

- Petersen PE, Kwan S. Equity, social determinants and public health programmes—the case of oral health. Community Dent Oral. 2011;39: 481-487.

- United States Department of Health and Human Services (US) Oral Health in America: a Report of the Surgeon General. Available at: nidcr.nih.gov/sites/default/files/2017-10/hck1ocv.%40www.surgeon.fullrpt.pdf. Accessed December 14, 2020.

- The Secretary’s Advisory Committee on National Health Promotion and Disease Prevention. Healthy People 2020. Available at: healthypeople.gov/2010/hp2020/advisory/PhaseI/PhaseI.pdf. Accessed December 14, 2020.

- American Medical Association. AMA Code of Medical Ethics. Available at: ama-assn.org/delivering-care/ethics/disparities-health-care. Accessed December 14, 2020.

- American Dental Association. Principles of Ethics and Code of Professional Conduct. Available at: ada.org/~/media/ADA/Member%20Center/Ethics/Code_Of_Ethics_Book_With_Advisory_Opinions_Revised_to_November_2018.pdf?la=en. Accessed December 14, 2020.

- American Dental Hygienists’ Association. Bylaws and Code of Ethics. Available at: adha.org/resources-docs/7611_Bylaws_and_Code_of_Ethics.pdf. Accessed December 14, 2020.

- American Nurses Association. Code of Ethics for Nurses. Available at: princetonhcs.org/-/media/princeton/documentrepository/documentrepository/nurses/code-of-ethics.pdf. Accessed December 14, 2020.

- Dunker A, Krofah E, Isasi F. The role of dental hygienists in providing access to oral health care. Available at: nga.org/files/live/sites/NGA/files/pdf/2014/1401DentalHealthCare.pdf. Accessed on December 14, 2020.

- United States Department of Health and Human Services. Designated Health Professional Shortage Areas Statistics. Available at: data.hrsa.gov/Default/GenerateHPSAQuarterlyReport. Accessed December 14, 2020.

- Edelstein BL. The dental caries pandemic and disparities problem. BMC Oral Health. 2006;6(Suppl 1):S2.

- United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Oral Health Surveillance Report. Available at: cdc.gov/oralhealth/publications/OHSR-2019-index.html. Accessed December 14, 2020.

- Fleming E, Afful J. Prevalence of total and untreated dental caries among youth: United States, 2015–2016. Available at: cdc.gov/nchs/data/databriefs/db307.pdf Accessed December 14, 2020.

- Eke PI, Dye B, Wei L, Thornton-Evans G, Genco R. Prevalence of periodontitis in adults in the United States: 2009 and 2010. J Dent Res. 2012;1–7.

- Genco RJ, Williams RC. 2nd ed. Periodontal Disease and Overall Health: A Clinician’s Guide. Yardley, Pennsylvania: Professional Audience Communications; 2010.

- Langelier M, Baker B, Continelli T. Development of a new dental hygiene professional practice index by state, 2016. Available at: oralhealthworkforce.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/02/OHWRC_Dental_Hygiene_Scope_of_Practice_2016.pdf. Accessed December 14, 2020.

- Wall T, Vujicic M. Emergency department use for dental conditions continues to increase. Available at: mediad.publicbroadcasting.net/p/wusf/files/201802/ADA.pdf. Accessed December 14, 2020.

- Wall T, Vujicic M. Emergency department visits for dental conditions fell in 2013. Available at: ada.org/~/media/ADA/Science%20and%20Research/HPI/Files/HPIBrief_0216_1.ashx. Accessed December 14, 2020.

- Kelekar U, Naavaal S. Hours lost to planned and unplanned dental visits among US adults. Prev Chronic Dis. 2018;5:170225.

- Naavaal S, Kelekar U. School hours lost due to acute/unplanned dental care. Health Behav Policy Rev. 2018;5:66–73.

- American Dental Hygienists’ Association. Direct Access Chart. Available at: adha.org/resources-docs/7513_Direct_Access_to_Care_from_DH.pdf. Accessed December 14, 2020.

- Johnson K, Gurenlian J, Garland K, Freudenthal J. State licensing board requirements for entry into the dental hygiene profession. J Dent Hyg. 2020;94:54–65.

- United States Department of Health and Human Services. Reforming America’s Healthcare System Through Choice and Competition. Available at: hhs.gov/sites/default/files/Reforming-Americas-Healthcare-System-Through-Choice-and-Competition.pdf. Accessed December 14, 2020.

- American Nurses Association. Interstate Nurse Licensure Compact. Available at: nursingworld.org/practice-policy/advocacy/state/interstate-nurse-compact2/. Accessed December 14, 2020.

- American Dental Education Association. Report of the Task Force on Assessment of Readiness for Practice. Available at: adea.org/TARPreport/. Accessed December 14, 2020.

- Arizona State Legislature. Bill History for HB2569. Available at: azleg.gov/legtext/54leg/1R/laws/0055.pdf. Accessed December 14, 2020.

- California Health Care Almanac. Health care Costs 101: Spending Keeps Growing. Available at: chcf.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/05/HealthCareCostsAlmanac2019.pdf. Accessed December 14, 2020.

- American Dental Association. Medicaid fee-for-service reimbursement rates for child and adult dental care services for all states, 2016. Health Policy Institute Research Brief. Available at: ada.org/~/media/ADA/Science%20and%20Research/HPI/Files/HPIBrief_0417_1.pdf. Accessed December 14, 2020.

- Borchgrevink A, Snyder A, Genshan S. Increasing access to dental care in Medicaid: does raising provider rates work? Available at: chcf.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/12/PDF-IncreasingAccessToDentalCareInMedicaidIB.pdf. Accessed December 14, 2020.

- American Dental Hygienists’ Association. Reimbursement. Available at: adha.org/reimbursement. Accessed December 14, 2020.

- Garcia RI, Inge RE, Niessen L, DePaola DP. Envisioning success: the future of the oral health care delivery system in the United States. J Public Health Dent. 2010;70:S58–S65.

- Koppelman J, Singer-Cohen R. A workforce strategy for reducing oral health disparities: dental therapists. Am J Public Health. 2017;107:S13–17.

- Rogo E. Synergy in social action: a dental hygiene theory. J Dent Hyg. 2018;92:6–17.

- Congress.gov. State Legislature Website. Available at: congress.gov/state-legislature-websites. Accessed December 14, 2020.

- Disney Educational Productions. Schoolhouse Rock: How a Bill Becomes a Law. Available at: youtube.com/watch?v=men-vp5jvzI. Accessed December 14, 2020.

- Rogo EJ, Bono LK, Petersen T. Developing dental hygiene students as future leaders in legislative advocacy. J Dent Educ. 2014;78:541–551.

- Project Vote Smart. Facts Matter. Available at: justfacts.votesmart.org/. Accessed December 14, 2020.

- American Dental Hygienists’ Association. Advocacy. Available at: adha.org/advocacy. Accessed December 14, 2020.

- American Dental Education Association. ADEA State Advocacy Toolkit. Available at: adea.org/state-advocacy-toolkit.aspx. Accessed December 14, 2020.

- United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Oral Health. Available at: cdc.gov/oralhealth/publications/index.htm. Accessed December 14, 2020.

- Bono LK, Rogo EJ, Hodges KO, Frantz AC. Post-graduation effects of an advocacy engagement process on alumni of a dental hygiene program. J Dent Educ. 2018;82:118–129.

- Rogo EJ. Evaluation of advocacy projects in undergraduate and graduate dental hygiene leadership courses. J Dent Educ. 2020; 84:871–880.

- MindTools. SWOT analysis: how to develop a strategy for success. Available at: mindtools.com/pages/article/newTMC_05.htm. Accessed December 14, 2020.

- American Dental Hygienists’ Association. Innovative Workforce Models. Available at: adha.org/workforce-models-adhp. Accessed December 14, 2020.

- Form Swift. Strategic plan template. Available at: formswift.com/strategic-plan-template. Accessed December 14, 2020.

- Online PC Learning. How to create a fact sheet using Microsoft Word and PPT. Available at: onlinepclearning.com/brochure-make-a-brochure-or-factsheet-that-rocks-microsoft word-. Accessed December 14, 2020.

From Dimensions of Dental Hygiene. January 2021;19(1):32-35.