Probiotics Provide Another Avenue to Enhance Oral Health

Probiotics offer potential benefits in addressing dental diseases, including caries and gingivitis, through various mechanisms that stabilize oral microbiota.

This course was published in the October/November 2024 issue and expires November 2027. The authors have no commercial conflicts of interest to disclose. This 2 credit hour self-study activity is electronically mediated.

AGD Subject Code: 010

EDUCATIONAL OBJECTIVES

After reading this course, the participant should be able to:

- Explain the importance of the oral microbiome.

- Identify the oral health benefits of probiotics.

- Discuss the safety and regulations surrounding the use of probiotics in dental and medical care.

The term probiotic originates from the Latin word “pro,” meaning “for” and the Greek word “bios,” meaning “life,” which translates to “for life.” This nomenclature was introduced in 1953 by the German scientist Werner Kollath, who defined probiotics as “active substances that are essential for a healthy development of life.”1 In 1965, the term evolved to describe compounds produced by bacteria that stimulate the growth of other microorganisms.

In 1989, probiotic was denoted as a supplement containing live microorganisms that promotes gut health of the host.1 In 2001, a joint meeting of the Food and Agricultural Organization (FAO) of the United Nations and World Health Organization (WHO) defined probiotics as “live microorganisms which when administered in adequate amounts confer a health benefit on the host;” this definition is currently used today.2

Studies have shown the use of probiotics is effective for the treatment of gut, skin, and vaginal problems, as well as supporting overall immune health.3,4 Probiotics are available in various forms, including fermented foods and beverages, liquids, pills, capsules, gummies, lozenges, and powders, and can be purchased via pharmacies, online retailers, grocery stores, and health food stores.5 Probiotics are also marketed in over-the-counter personal care products, such as deodorants, soap bars, foundations, cleansers, gels, balms, exfoliants, serums, masks, and creams.6 Potential benefits of probiotics in oral health include preventing and treating caries, periodontal diseases, oral infections, oral malodor, and oral cancer.7,8

Oral Microbiome

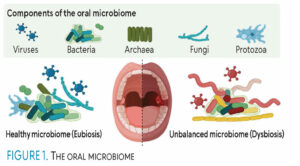

The oral cavity is a haven to more than 700 microbial species, including bacteria, fungi, viruses, protozoa, and archaea. Microbial communities inhabiting the mouth are referred to as the oral microbiome, oral microflora, or oral microbiota.7-9 Inhabitants adhere to one another and reside on oral tissues including the teeth, tongue, buccal mucosa, subgingival crevice, hard and soft palate, and oropharynx.

The temperature of the oral cavity makes it an ideal place for microbes to flourish and the neutrality of the saliva (6.5 to 7.0 pH) permits these microbes, particularly bacteria, to stay hydrated and transport nutrients. The most abundant strains of bacteria in a healthy mouth consist of both Gram-positive and Gram-negative cocci and rods with colonization beginning shortly after birth.9

These microorganisms live together in symbiosis, where many do not cause harm. However, when this symbiotic relationship is disrupted, dysbiosis occurs, increasing the risk of oral and systemic diseases (Figure 1).9 Oral microbiome disruptions may result from smoking, alcohol use, socioeconomic status, antibiotic use, diet, and pregnancy.7

Pathogenesis resulting from an altered oral microbiome includes but is not limited to autoimmune diseases, bacteremia, cancer, dental caries, diabetes, endocarditis, periodontitis, gingivitis, oral malodor, preterm births, recurrent aphthous stomatitis, obesity, and neurological diseases.7,8,10-12 Thus, the use of probiotics is beneficial for the oral cavity by promoting healthy bacteria and preventing those that cause disease.13

Pathogenesis resulting from an altered oral microbiome includes but is not limited to autoimmune diseases, bacteremia, cancer, dental caries, diabetes, endocarditis, periodontitis, gingivitis, oral malodor, preterm births, recurrent aphthous stomatitis, obesity, and neurological diseases.7,8,10-12 Thus, the use of probiotics is beneficial for the oral cavity by promoting healthy bacteria and preventing those that cause disease.13

Probiotics improve oral health through various mechanisms at either the local or systemic level. Probiotics compete for nutrient sources and adhesion sites, raise secretory immunoglobulin A levels in saliva, release antimicrobial substances, decrease plaque formation, and increase salivary secretion.14 Through these mechanisms, probiotics provide beneficial effects for the treatment and reduction of caries, gingivitis, periodontitis, candida, oral malodor, and oral cancer (Table 1).

Dental Caries

The main causative microbes involved in dental caries include Streptococcus mutans, S. sobrinus, and Lactobacilli. These oral bacteria metabolize fermentable carbohydrates in the diet, causing the pH of the oral environment to become acidic. The persistence of this acidic environment leads to tooth demineralization.15

Certain species of probiotics have been shown to help reduce caries. Lactobacillus kefiranofaciens found in kefir effectively inhibited both S. mutans and S. sobrinus in an in vitro study.16 L. kefiranofaciens inhibited the expression of several bacterial genes including those that encoded for carbohydrate metabolism, adhesion, and other regulatory mechanisms.16 The strain L. rhamnosus inhibited Streptococcus by producing various antimicrobial compounds such as organic acid, hydrogen peroxide, carbon peroxide and diacetyl bacteriocins.17 S. dentisani inhibited the growth of S. mutans, Fusobacterium nucleatum, and Prevotella intermedia by producing bacteriocins, and buffering the acidic pH of the oral cavity.18 Lactococcus lactis reduced the colonization of S. oralis, Veillonella dispar, Actinomyces naeslundii, and S. sobrinus.19

Gingivitis

The inflammatory response from gingivitis often results in tissue destruction from the Gram-negative anaerobic bacteria Porphyromonas gingivalis, which colonize subgingivally and invade epithelial cells. Inflammatory gingipain proteases produced by P. gingivalis contribute to the degradation of the host complement system, leading to inflammation. Different strains of bacteria in probiotics help reduce gingivitis by stabilizing the oral cavity’s microbial balance. Bacteria, including Lactobacilli, Streptococci, and Bifidobacterium, release antimicrobials that inhibit pathogens such as P. gingivalis. They achieve this through co-aggregation, producing toxic byproducts, and competing for available nutrients. Chewing gum containing L. reuteri reduced inflammatory markers in the gingival crevicular fluid reducing gingivitis. Lozenges containing L. reuteri helped control gingivitis in pregnant women.8

Periodontitis

Periodontitis is initiated when several virulent Gram-negative anaerobic bacteria encompassed in oral biofilm invade the gingival crevice. The lipopolysaccharide component of the cell wall of these pathogenic bacteria evokes an immune response and alters homeostasis, resulting in destruction of the periodontium.20 Probiotics containing Lactobacillus strains prevent periodontitis by stabilizing the oral microbiota.8 Studies using L. ruteri, L. brevis, L. rhamnosus, and L. salivarius inhibited the growth of virulent periodontal pathogens and helped reduce the release of inflammatory markers.21

Another study using orally administered Lactobacillus strains demonstrated a reduction in bone resorption.22 Furthermore, L. reuteri-containing lozenges used twice per day for 3 weeks as an adjunct to clinical treatment of periodontitis showed a significant reduction in the number of anaerobic bacteria in subgingival plaque, as well as less bleeding and periodontal pockets.23

Candida Infections

The usually harmless fungus Candida albicans may become pathogenic and is the main culprit in oral fungal infections. Approximately 30% to 60% of adults present with oral candida.24 In vitro studies have shown promising results in which L. rhamnosus, L. casei, and L. acidophilus have helped prevent biofilm formation through acid production, cell adhesion, and even the morphological transition of fungi yeast-to-hyphae.25,26

Additional in vitro studies suggest that L. plantarum, L. helveticus, and S. salivarius alter gene expression, thereby inhibiting the formation of C. albicans.25,26 An in vitro study demonstrated that L. reuteri reduced C. albicans by producing lactic acid and other acids, which promote co-aggregation and alter oral pH.26

Oral Malodor

Oral malodor, or bad breath, can result from certain foods, medications, use of alcohol and tobacco products, or bacterial degradation from the presence of oral diseases and poor oral hygiene.27 Additional causes include several systemic diseases, such as kidney and liver diseases, diabetes, oropharyngeal infections, and gastritis as a result of the bacteria Helicobacter pylori.28

The unpleasant odor is created when Gram-negative bacteria (F. nucleatum, P. gingivalis, P. intermedia, and Treponema denticola) break down food debris to produce volatile sulfur compounds (VSCs), which are the main source of oral malodor due to dysbiosis of the normal oral microflora. Oral rinses, chewing gums, and lozenges can address oral malodor. However, many products are effective only in the short-term and only mask malodor. Incorporating strains of probiotics in these products has been shown to be more effective in reducing oral malodor.8

A study using orally administered L. reuteri, L. salivarius, and L. acidophilus showed a significant reduction in oral malodor by minimizing pathogenic bacteria comprised in biofilm. In a separate study, chewing gum with the strain L. reuteri reduced oral malodor in the same manner.29 A study that evaluated probiotic tablets containing L. salivarius taken three times a day showed a reduction in VSCs.30 Furthermore, using an oral rinse containing the probiotic Weissella cibaria showed a significant reduction in oral malodor by inhibiting the Gram-negative bacteria F. nucleatem.31

Oral Cancer

The role of probiotics in treating various types of oral cancer is fairly new and still emerging, with in vitro and in vivo studies being conducted.32 Multiple strains of Bifidobacterium and Lactobacillus have been shown to have anticancer properties through induction of programmed cell death (apoptosis), preventing the formation of new blood vessels (angiogenesis), and stimulating or suppressing the immune system (modulation).33 Additionally, probiotics may be beneficial in quelling side effects for patients undergoing cancer therapy.34

Safety and Regulation of Probiotics

While research supports the benefits of probiotics, the efficacy of a probiotic for one condition does not guarantee its effectiveness for another. Currently, no standards exist for effective doses of probiotics for oral health;14 therefore, converting research findings into clinical recommendations can be challenging. A growing number of studies suggest that probiotics demonstrate a favorable safety profile;35-37 however, existing research suggests reporting of potential adverse events and safety is insufficient.38 Thus, the frequency and severity of side effects are unknown.

Although adverse events are not common, those at increased risk include immunocompromised individuals, the critically ill, and those with short bowel syndrome or comorbidities. The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) recently issued a warning stating that the use of probiotics in preterm infants is associated with mortality.39 A systematic review examining studies of adverse events associated with probiotics found that the reporting of harms in randomized clinical trials is vague and insufficient.38 Specifically, of the 384 trials reviewed, 309 (80%) did not report adverse events, and 142 (37%) did not provide information on safety results.

Regulatory oversight for probiotics reveals international differences and safety requirements that differ from one country to another.35 In the US, the FDA regulates probiotics as either a dietary supplement or a food ingredient under self-affirmed “generally recognized as safe” status, which has less stringent manufacturing and regulatory requirements than drugs.35 In fact, probiotics sold as dietary supplements are not required to be approved by the FDA before sold to consumers; however, companies are not permitted to make health claims regarding efficacy without prior FDA approval.40

The FAO and WHO have identified four criteria to qualify microorganisms as probiotics for use in food and dietary supplements.41 Probiotic strains must be:

- Sufficiently characterized

- Safe for the intended use

- Supported by at least one positive human clinical trial conducted according to generally accepted scientific standards or as per recommendations and provisions of local/national authorities when applicable

- Alive in the product at an efficacious dose throughout shelf life

Although the FDA does not provide a list of approved probiotics, it ensures they are safe for human consumption by requiring them to be produced in facilities that comply with certain requirements.35 Thus, the manufacturer is responsible for adhering to safety guidelines.

Conclusion

While evidence suggests that probiotics are safe, consideration of the risk-benefit ratio before prescribing is recommended. Research on the oral health benefits of probiotics is available; however, more studies are needed to establish clear guidelines for their use. Dental hygienists must consult the manufacturer’s instructions for use and consideration must be given to safety, regulation, and potential adverse effects.35-39 Clinicians should consider the specific probiotic strain, dosage, quality of the product, and host factors before including probiotics as a standard of care.

References

- Gasbarrini G, Bonvicini F, Gramenzi A. Probiotics history. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2016;50 Suppl 2, Proceedings from the 8th Probiotics, Prebiotics & New Foods for Microbiota and Human Health meeting held in Rome, Italy on September 13-15, 2015:S116-S119. doi:10.1097/MCG.0000000000000697.

- Joint FAO/WHO Expert Consultation on Evaluation of Health and Nutritional Properties of Probiotics in Food including Powder Milk with Live Lactic Acid Bacteria. 1-4 October 2001. ISBN 92-5-105513-0.

- Das TK, Pradhan S, Chakrabarti S, Mondal KC, Ghosh K. Current status of probiotic and related health benefits. Applied Food Research, 2022;2(2), 100185. Doi:10.1016/j.afres.2022.100185.

- Wiciński M, Gębalski J, Gołębiewski J, Malinowski B. Probiotics for the treatment of overweight and obesity in humans-a review of clinical trials. Microorganisms. 2020;8(8):1148. doi:10.3390/microorganisms8081148.

- Asaithambi N, Singh S K, Singha P. Current status of non-thermal processing of probiotic foods: A review. J of Food Eng, 2021;303. doi.:10.1016/j.jfoodeng.2021.110567.

- Puebla-Barragan S, Reid G. probiotics in cosmetic and personal care products: trends and challenges. Molecules. 2021;26(5):1249. doi:10.3390/molecules26051249.

- Lee YH, Chung SW, Auh QS, et al. Progress in Oral Microbiome Related to Oral and Systemic Diseases: An Update. Diagnostics (Basel). 2021;11(7):1283. Published 2021 Jul 16. doi:10.3390/diagnostics11071283.

- Chugh P, Dutt R, Sharma A, Bhagat N, Dhar MS. A critical appraisal of the effects of probiotics on oral health. Journal of Functional Foods, 2020;70:103985. doi: 10.1016/j.jff.2020.103985.

- Deo PN, Deshmukh R. Oral microbiome: Unveiling the fundamentals. J Oral Maxillofac Pathol. 2019;23(1):122-128. doi:10.4103/jomfp.JOMFP_304_18.

- Verma D, Garg PK, Dubey AK. Insights into the human oral microbiome. Arch Microbiol. 2018;200(4):525-540. doi:10.1007/s00203-018-1505-3.

- Zhu Z, He Z, Xie G, Fan Y, Shao T. Altered oral microbiota composition associated with recurrent aphthous stomatitis in young females. Medicine (Baltimore). 2021;100(10):e24742. doi:10.1097/MD.0000000000024742.

- Pitts NB, Twetman S, Fisher J, Marsh PD. Understanding dental caries as a non-communicable disease. Br Dent J. 2021;231(12):749-753. doi:10.1038/s41415-021-3775-4.

- Mann S, Park MS, Johnston TV, Ji GE, Hwang KT, Ku S. Oral probiotic activities and biosafety of Lactobacillus gasseri HHuMIN D. Microb Cell Fact. 2021;20(1):75. doi:10.1186/s12934-021-01563-w.

- Babina K, Salikhova D, Polyakova M, Zaytsev A, Egiazaryan A, Novozhilova N. Knowledge and attitude towards probiotics among dental students and teachers: A cross-sectional survey. Dent J (Basel). 2023;11(5):119. doi:10.3390/dj11050119.

- Rathee M, Sapra A. Dental Caries. [Updated 2023 Jun 21]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2024 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK551699/.

- Jeong D, Kim DH, Song KY, Seo KH. Antimicrobial and anti-biofilm activities of Lactobacillus kefiranofaciens DD2 against oral pathogens. J Oral Microbiol. 2018;10(1):1472985. Published 2018 May 28. doi:10.1080/20002297.2018.1472985.

- Piqué N, Berlanga M, Miñana-Galbis D. Health Benefits of Heat-Killed (Tyndallized) Probiotics: An Overview. Int J Mol Sci. 2019;20(10):2534. Published 2019 May 23. doi:10.3390/ijms20102534.

- López-López A, Camelo-Castillo A, Ferrer MD, Simon-Soro Á, Mira A. Health-Associated Niche Inhabitants as Oral Probiotics: The Case of Streptococcus dentisani. Front Microbiol. 2017;8:379. Published 2017 Mar 10. doi:10.3389/fmicb.2017.00379.

- Huang R, Li M, Gregory RL. Bacterial interactions in dental biofilm. Virulence. 2011;2(5):435-444. doi:10.4161/viru.2.5.16140.

- Könönen E, Gursoy M, Gursoy UK. Periodontitis: A multifaceted disease of tooth-supporting tissues. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2019; 8(8):1135. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm8081135.

- Allaker RP, Stephen AS. Use of Probiotics and Oral Health. Curr Oral Health Rep. 2017;4(4):309-318. doi:10.1007/s40496-017-0159-6.

- Matsubara VH, Bandara HM, Ishikawa KH, Mayer MP, Samaranayake LP. The role of probiotic bacteria in managing periodontal disease: A systematic review. Expert Rev Anti Infect Ther. 2016;14(7):643-655. doi:10.1080/14787210.2016.1194198.

- Tekce M, Ince G, Gursoy H, et al. Clinical and microbiological effects of probiotic lozenges in the treatment of chronic periodontitis: a 1-year follow-up study. J Clin Periodontol. 2015;42(4):363-372. doi:10.1111/jcpe.12387.

- Singh A, Verma R, Murari A, Agrawal A. Oral candidiasis: An overview. J Oral Maxillofac Pathol. 2014;18(Suppl 1):S81-S85. doi:10.4103/0973-029X.141325.

- James KM, MacDonald KW, Chanyi RM, Cadieux PA, Burton JP. Inhibition of Candida albicans biofilm formation and modulation of gene expression by probiotic cells and supernatant. J Med Microbiol. 2016;65(4):328-336. doi:10.1099/jmm.0.000226.

- Jørgensen MR, Kragelund C, Jensen PØ, Keller MK, Twetman S. Probiotic Lactobacillus reuteri has antifungal effects on oral Candida species in vitro. J Oral Microbiol. 2017;9(1):1274582. Published 2017 Jan 18. doi:10.1080/20002297.2016.1274582.

- Memon MA, Memon HA, Muhammad FE, et al. Aetiology and associations of halitosis: A systematic review. Oral Dis. 2023;29(4):1432-1438. doi:10.1111/odi.14172.

- Anbari F, Ashouri Moghaddam A, Sabeti E, Khodabakhshi A. Halitosis: Helicobacter pylori or oral factors. Helicobacter. 2019;24(1):e12556. doi:10.1111/hel.12556.

- Soares LG, Carvalho EB, Tinoco EMB. Clinical effect of Lactobacillus on the treatment of severe periodontitis and halitosis: A double-blinded, placebo-controlled, randomized clinical trial. Am J Dent. 2019;32(1):9-13.

- Suzuki N, Higuchi T, Nakajima M, et al. Inhibitory Effect of Enterococcus faecium WB2000 on Volatile Sulfur Compound Production by Porphyromonas gingivalis. Int J Dent. 2016;2016:8241681. doi:10.1155/2016/8241681

- Kang MS, Kim BG, Chung J, Lee HC, Oh JS. Inhibitory effect of Weissella cibaria isolates on the production of volatile sulphur compounds. J Clin Periodontol. 2006;33(3):226-232. doi:10.1111/j.1600-051X.2006.00893.x.

- Singh D, Khan MA, Siddique HR. Therapeutic implications of probiotics in microbiota dysbiosis: A special reference to the liver and oral cancers. Life Sci. 2021;285:120008. doi:10.1016/j.lfs.2021.120008.

- Nami Y, Tavallaei O, Kiani A, et al. Anti-oral cancer properties of potential probiotic lactobacilli isolated from traditional milk, cheese, and yogurt. Sci Rep. 2024;14(1):6398. Published 2024 Mar 16. doi:10.1038/s41598-024-57024-y.

- Rodriguez-Arrastia M, Martinez-Ortigosa A, Rueda-Ruzafa L, Folch Ayora A, Ropero-Padilla C. Probiotic Supplements on Oncology Patients’ Treatment-Related Side Effects: A Systematic Review of Randomized Controlled Trials. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(8):4265. doi:10.3390/ijerph18084265.

- Roe AL, Boyte ME, Elkins CA, et al. Considerations for determining safety of probiotics: A USP perspective. Regul Toxicol Pharmacol. 2022;136:105266. doi:10.1016/j.yrtph.2022.105266.

- Li D, Li Q, Liu C, et al. Efficacy and safety of probiotics in the treatment of Candida-associated stomatitis. Mycoses. 2014;57(3):141-146. doi:10.1111/myc.12116.

- Diwas Pradhan, Rashmi H. Mallappa, Sunita Grover, Comprehensive approaches for assessing the safety of probiotic bacteria, Food Control, Volume 108, 2020, 106872, ISSN 0956-7135, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodcont.2019.106872.

- Bafeta A, Koh M, Riveros C, Ravaud P. Harms reporting in randomized controlled trials of interventions aimed at modifying microbiota: A systematic review. Ann Intern Med. 2018;169:240-247. doi:10.7326/M18-0343.

- Food and Drug Administration. Risk of invasive disease in preterm infants given probiotics formulated to contain live bacteria or yeast. Published September 29, 2023. https://www.fda.gov/safety/medical-product-safety-information/risk-invasive-disease-preterm-infants-given-probiotics-formulated-contain-live-bacteria-or-yeast.

- Food and Drug Administration. Statement from FDA Commissioner Scott Gottlieb, M.D., on advancing the science and regulation of live microbiome-based products used to prevent, treat, or cure diseases in humans. Published August 16, 2018. https://www.fda.gov/news-events/press-announcements/statement-fda-commissioner-scott-gottlieb-md-advancing-science-and-regulation-live-microbiome-based.

- Binda S, Hill C, Johansen E, et al. Criteria to Qualify Microorganisms as “Probiotic” in Foods and Dietary Supplements. Front Microbiol. 2020;11:1662. Published 2020 Jul 24. doi:10.3389/fmicb.2020.01662.

From Dimensions of Dental Hygiene. October/November 2024; 22(6):50-53.