PREVENTIVE POSITIONING

Maintaining good posture while practicing will minimize neck, shoulder, and low back pain.

How often have you experienced this scenario? Working on the last patient of the day, you can hardly stand the pain in your right upper back—just under the shoulder blade. In an effort to relieve the pain, you complete the task by gulping down naproxen and resting your right elbow on the patient’s headrest.

Many dental hygienists experience this type of pain or discomfort in other areas like the neck, shoulder, or low back. Studies of dental hygienists from around the world reveal that as many as 80% of dental hygienists complain of pain in the upper body and back1 and that the most frequently experienced health problems for dental hygiene practitioners are primarily associated with the back and neck, followed by the hand and wrist.2

Causes of Injury

Most of this type of musculoskeletal pain derives from cumulative trauma disorders (CTDs), musculoskeletal disorders (MSDs), or repetitive strain injuries from neuromuscular conditions, which result from cyclic exertion of low-level static muscle contraction and/or dynamic contractions where the activity is prolonged for several hours. Providing dental hygiene services almost always requires maintaining the same working postures and using repetitive actions for extended periods of time.

Low-level static exertions occur when there is muscle contraction without movement, such as when the clinician lifts her shoulder on the dominant side in order to compensate for poor patient or clinician positioning. Injury can occur when the contraction is maintained for a sustained period of time and if the clinician is not in a protective posture (neutral position) to keep muscles from compressing on blood vessels, which reduces the blood flow to muscles.

Low-level static muscle contractions can result in fibrosis, especially in occupations requiring precision movements and static postures like dental hygiene practice. Exactly how long it takes for injury to occur depends on the individual, particularly on how physically fit and healthy the muscles are. On the other hand, activities that involve dynamic contractions (with muscle movement) can also cause problems if the contractions are repetitive in nature and/or posture is poor. Muscle fatigue can result from either static or dynamic exertions that add up to muscle work overload.3

Another factor that may contribute to pain from poor posture is forward flexion of the neck. The neck requires extensive muscle power to hold it in place when the head is out of a neutral position. Imagine how much effort it would take to hold a 10-12 pound bowling ball attached to a mop handle at an angle. This is how much muscle power is needed for the neck to keep the head steady when it is not balanced.

Vision and Magnification

Forward flexion can result from poor vision or poor positioning, which affects vision. The use of magnification loupes is an effective way to maintain the neck in neutral position. The clinician should work with a vendor who is knowledgeable about the correct loupes for the work done and who can adjust the loupes for the individual and for the job at hand because poorly adjusted scopes can be just as detrimental as none at all.

If the root cause is a vision problem, posture will not improve until vision is improved. Dental hygienists need to have their vision checked regularly. The eye care professional also needs to know that the normal working distance for dental hygienists is 14 to 16 inches so that the corrective lenses are appropriate for dental hygiene practice.

The Importance of Rest

Once a muscle motor unit—the muscle, attached tendon, and controlling motor nerve—is fatigued, there must be a rest period for full recovery. The length of the recovery period depends on many factors, such as type of motion, intensity of the load, and duration of the sustained contraction. Longer contractions generally require longer recuperation time and can result in a higher chance of efficiency and precision loss in the work. Muscle overload alone can also damage the muscle.

When the dental hygienist is concentrating on the task at hand, one of the dangers with low-level static exertions is that normal signs of fatigue may be ignored and overloaded muscles fibers are deprived of their needed corresponding rest cycle. If the lack of rest cycle goes on for a long enough time period, the circulatory and metabolic mechanisms may be damaged, which can lead to necrosis of the muscle cells. The long-term effects could then be replacement of muscle tissue with fibrotic or scar tissue.3

Posture

Understanding how injury occurs on a practical level can help determine preventive strategies. Poor posture is probably the most frequent etiologic factor in occupational back pain in the dental hygienist. Work postures that put muscles into low-level static exertion are common for dental hygienists and to compound the problem, protective postures are often overlooked once the focus is on the patient’s needs. Slowly the hygienist begins to resort to whatever compensation necessary to get the job done.

Following are three simple rules to improve posture:

- Keep your spine and neck in neutral position.

- Keep your body facing your work.

- Keep your shoulders down and relaxed.

Neutral Position

The neutral position is the position where bones, joints, ligaments, and muscles are aligned at rest and in which the spine is held in an optimal position, allowing equal distribution of force through the entire structure.

To find the neutral position for your neck and spine:

- Sit comfortably on an adjustable stool or chair with feet flat on the floor, toes pointing straight ahead.

- Knees should be relaxed and over your heels, not forward of the heels.

- Adjust the chair so that the knees are at a 90º angle.

- Place hands on thighs.

- Shoulders should be back slightly. The shoulders and arms should be relaxed.

- Adjust spine position so that you are not arching your lower back or compressing it (slouching).

- Looking straight ahead, balance the head.

See Figure 1 for an example of a neutral working position.

The spine has three natural curves when the body is in neutral position. They are in the cervical area (neck), thoracic region (upper back), and lumbar region (lower back). Proper alignment of the spine means keeping these natural curves supported, not collapsed or slumped. Do not try to flatten out any of these curves, since this results in tucking of the pelvis or holding in the neck and upper back. Picture your spine as a gentle S curve, with each vertebrae stacked gently on top of each other (see Figure 2 for how neutral looks with different body types.)

The spine has three natural curves when the body is in neutral position. They are in the cervical area (neck), thoracic region (upper back), and lumbar region (lower back). Proper alignment of the spine means keeping these natural curves supported, not collapsed or slumped. Do not try to flatten out any of these curves, since this results in tucking of the pelvis or holding in the neck and upper back. Picture your spine as a gentle S curve, with each vertebrae stacked gently on top of each other (see Figure 2 for how neutral looks with different body types.)

When you sit, you should feel your ears balanced over your shoulders, your shoulders over your hips, and your spine lifted. Whenever possible, sit back against the lumbar support or the back of your stool or chair so that your lumbar curve is supported and release your upper back into the back of the stool. If your stool doesn’t have lumbar support, you need a new one. At the very least, roll up a towel and attach it to the stool back to provide support. Keep your chin level, not pushed down or tilted upwards.

It often takes some training of the postural muscles to maintain proper posture. Most of us need to exercise in order to develop and maintain appropriate postural muscles. If a personal trainer is not in your budget, there are numerous websites like www.bodyzone.com/custom/posture_exercise.html that can provide tips on exercises to strengthen postural muscles. See Table 2 for more resources.

Face Your Work

To maintain correct posture in order to avoid stress on the back, remaining in neutral position is critical except for those rare times when the clinician must deviate for a short time because of some special patient factor. In order to work efficiently, effectively, and be as easy on the body as possible, the clinician should be facing the area of work at all possible times.

One of the most consistent bad habits that dental hygienists maintain is sitting at 11:00 for right-handed people and 1:00 for those left-handed. This odd position is probably an effort to stay out of the patient’s space. There is almost no work that can be done from this position without serious out-of-neutral positioning. The only area of instrumentation that can be accomplished correctly from this position is in the left mandibular canine (right canine for the left-handed). For example, when working on the mandibular posterior, the clinician should be facing the area by sitting with the legs apart somewhere between 8:30 and 9:30 (2:30 – 3:30 left) depending on the curve of the patient’s mandible. See Figure 3 for an example of incorrect positioning.

Trying to work with the knees together is another bad habit. Just as keeping the pinky finger tight against the other fingers is not good for hand and wrist posture, sitting with the knees together is seldom the best way to maintain correct protective posture.

Each area of instrumentation has a corresponding best position, including where the legs need to be, that allow the clinician to face the work in order to maintain neutral posture. Ask a friend or coworker to pose as a patient and then find the best places to sit so your body faces the area of instrumentation. The positions you discover may be quite different than the way you usually work.

SHOULDERS DOWN AND RELAXED

Since keeping shoulders elevated and tense is probably one of the leading causes of postural-induced pain, it deserves special attention. Take note of where your shoulders are and learn to feel when you begin to tense the muscles. There are actually two major causes of this problem: poor patient positioning and stress response.

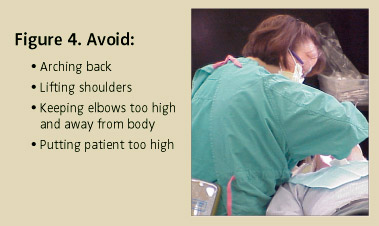

Poor patient positioning causes the clinician to lift the shoulder, which often results from having the patient too high. The proper work height is determined by the clinician’s height and the task (exposing radiographs, scaling, etc) at hand. Often, perhaps in trying to keep the knees together and under the chair, we raise the patient so high that we can’t reach the area of work without pulling the shoulder up. Figure 4 shows an example of this unhealthy posture. While having the patient too high is a more common problem, if the patient is positioned too low, it can cause low back problems because you need to arch your back to see. Remember that the area of instrumentation should be at elbow height—with shoulders down and relaxed—not too high and not too low.

Develop a keen conscious awareness of the tension in your shoulders and back. Ask coworkers to tell you if they see your dominant side shoulder in the air or when you feel the tension, make a deliberate effort to drop and relax the shoulders. At first, this will be a challenge, but once you reap the reward of a pain free workday, it will be well worth the effort.

The most important advice for hygienists who spend their days caring for other people’s health is to remember your own. Learn what you can to make your work day as physically stress and pain free as possible. Make an effort to listen and read about ergonomics with an open mind, not set on your way being the only way. Try out suggestions to improve your posture. The bottom line is if you refuse to change and you ignore your symptoms, your days in clinical practice will be numbered.

REFERENCES

- Oberg T, Oberg U. Musculoskeletal complaints in dental hygiene: a survey study from a Swedish country. J Dent Hyg. 1993:67:257-261.

- Boyer, EM, Elton, J. Preston, K. Precautionary procedures. Use in dental hygiene practice. Dent Hyg. 1986;60:516-523.

- Murphy DC. Ergonomics and the Dental Care Worker. Washington, DC: American Public Health Association; 1998.

- CTD Resource Network. Available at: www.tifaq.com/information/glossary.html. AccessedFebruary 20, 2004.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

- Akesson I, Johnsson B, Rylander L, Mortitz U, Skerfving S. Musculoskeletal disorders among female dental personnel—clinical examination and a 5-year follow-up study of symptoms. Int Arch Occup Environ Health. 1999;72:395-403.

- Shenkar O, Mann J, Shevach A, Ever-Hadani P, Weiss PL. Prevalence and risk factors of upper extremity cumulative trauma disorders in dental hygienists. Work. 1998;11:363-374.

- Stentz TL, Riley MW, StantonDH, Sposato RC, Stockstill JW, Harn JA. Upper extremity altered sensations in dental hygienists. Journal of Industrial Ergonomics.1994;13:107-112.

From Dimensions of Dental Hygiene. March 2004;2(3):12-14, 16, 18-19.