Preventing Infectious Endocarditis

An update on the American Heart Association prophylactic guidelines.

The American Heart Association (AHA) prophylactic guidelines have undergone changes in the past year. Understanding these changes is important to ensuring the safe treatment of your patients.

INFECTIVE ENDOCARDITIS

Infective endocarditis (IE) is a microbial infection of the heart valves or surface of the heart that is uncommon but can be life threatening. IE is caused by bacteremia (bacteria in the blood). Bacteremia can occur during dental procedures that involve bleeding. Trauma from scaling and root planing can rupture blood vessels in the gingival sulcus. The pressure from this trauma forces microorganisms into the blood.1 Bacteremia may also be caused by routine daily activities, such as chewing, toothbrushing, and using interdental aids.

The bacteria in the bloodstream can settle on damaged heart valves, prosthetic valves, and other susceptible areas. An infection may occur, diminishing function by the formation of vegitations (composed of bacteria masses and blood clots), which can then lodge on the endocardium and start to multiply.2 These growths may break off and travel to the brain, lungs, kidneys, or spleen. Streptococcus viridians is responsible for approximately half of all bacterial endocarditis.2 Other common microorganisms include Staphylococcus aureus and Enterococcus.3

TABLE 1. PATIENTS WITH THE FOLLOWING CONDITIONS NO LONGER REQUIRE PROPHYLACTIC ANTIBIOTICS:4

- Mitral valve prolapse

- Rheumatic heart disease

- Bicuspid valve disease

- Calcified aortic stenosis

- Congenital heart condition, like ventricular septal defect, atrial defect, and hypertophic cardiomyopathy

AHA GUIDELINES FOR PREVENTIVE ANTIBIOTICS

Since 1955, the AHA has made prophylactic antibiotic recommendations for the prevention of IE. In April 2007, the AHA published its latest guidelines in its scientific journal, Circulation. See Tables 1 and 2 for the conditions that no longer require prophylactic antibiotic recommendations and those that do.

The conditions requiring prophylactic antibiotic treatment have the highest risk of adverse outcome from endocarditis. Older age, diabetes mellitus, immunosuppressive conditions or therapy, and dialysis are comorbid factors that may complicate IE and often occur in combination, which can further increase morbidity and mortality rates.

IE prophylaxis is recommended for patients with the conditions listed in Table 2 for all dental procedures that involve manipulation of gingival tissue or the periapical region of teeth or perforation of the oral mucosa. The following procedures and events do not need prophylaxis: routine anesthetic injections through noninfected tissue, taking dental radiographs, placement of removable prosthodontic or orthodontic appliances, adjustment of orthodontic appliances, placement of orthodontic brackets, shedding of deciduous teeth, and bleeding from trauma to the lips or oral mucosa.2

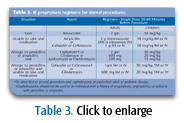

Antibiotic prophylaxis is recommended 30-60 minutes prior to treatment. If the antibiotic is not administered beforehand, the dosage may be given up to 2 hours after the procedure. However, patients who do not receive the preprocedure dose may experience coincidental endocarditis during invasive procedures.2 Table 3 provides the IE prophylaxis regimens for dental procedures.

TABLE 2. THE NEW RECOMMENDATIONS SUGGEST ANTIBIOTIC TREATMENT FOR PATIENTS WITH THE FOLLOWING CONDITIONS:2

- Prosthetic cardiac valve.

- Previous infective endocarditis.

- Congenital heart disease (CHD)*.

- Unrepaired cyanotic CHD, including palliative shunts and conduits.

- Completely repaired congenital heart defect with prosthetic material or device, whether placed by surgery or by catheter intervention during the first 6 months after the procedure because endothelialization of prosthetic material occurs within 6 months of the procedure.

- Repaired CHD with residual defects at the site or adjacent to the site of a prosthetic patch or prosthetic device, which inhibit endothelialization.

- Cardiac transplantation recipients who develop cardiac valvulopathy.

* Except for the conditions listed above, antibiotic prophylaxis is no longer recommended for any other form of CHD.

REASON FOR REVISION

Previous AHA guidelines on the prevention of IE were not well established and were largely based on expert opinion and limited case studies. The latest recommendations were developed through an evidence-based approach using a collective body of research that has been published over the past 20 years and extensively reviewed.2,5 The 1997 document was also very complicated, making it difficult for patients and health care providers to interpret or remember.2

Antimicrobial prophylaxis prior to dental treatments is thought to effectively prevent IE, but there is a lack of published data to support this benefit. In fact, numerous publications have questioned the validity of its effectiveness.6,7 However, the possibility of prevention cannot be excluded. The new AHA guidelines restrict the use of prophylaxis to those patients with the highest risk of adverse outcome from IE and to those who will gain the greatest benefit from prevention.2

The new guidelines reduce the number of conditions that necessitate IE prophylaxis due in part to the risks associated with antibiotics, such as the widespread emergence of resistant microorganisms most likely to cause endocarditis. For the past 20 years, the frequency of multidrug-resistant viridans group streptococci and enterococci has increased dramatically, reducing the efficacy and number of antibiotics available for the treatment of IE.2 Other adverse reactions may include rash, diarrhea, or gastro-intestinal upset.7 Fatality due to allergy may occur, but is extremely rare.

Reported cases of IE due to oral bacteremia most likely result from routine daily activities rather than dental procedures. A vast majority of these cases include patients who did not receive dental treatments within 2 weeks of the onset of IE symptoms. Therefore, it cannot be determined definitively if the bacteremia that caused the IE originated from the dental procedure or from routine daily activities. The frequency of bacteremia occurring due to routine daily activities is far greater than bacteremia occurring from dental procedures since the average American receives less than two dental visits per year.

Reported cases of IE due to oral bacteremia most likely result from routine daily activities rather than dental procedures. A vast majority of these cases include patients who did not receive dental treatments within 2 weeks of the onset of IE symptoms. Therefore, it cannot be determined definitively if the bacteremia that caused the IE originated from the dental procedure or from routine daily activities. The frequency of bacteremia occurring due to routine daily activities is far greater than bacteremia occurring from dental procedures since the average American receives less than two dental visits per year.

MOVING FORWARD

Following are the AHA recommendations to help clinicians in re-educating their patients about the IE prophylaxis guideline changes:2

- IE is much more likely to result from frequent exposure to random bacteremias associated with daily activities than from bacteremia caused by a dental, gastro-intestinal tract, or genitourinary tract procedure.

- Prophylaxis may prevent an exceedingly small number of cases of IE, if any, in individuals who undergo a dental, gastro-intestinal tract, or genitourinary tract procedure.

- The risk of antibiotic-associated adverse events exceeds the benefit, if any, from prophylactic antibiotic therapy.

- Maintenance of optimal oral health and hygiene may reduce the incidence of bacteremia from daily activities.

LEGAL PERSPECTIVE

The 2007 AHA guidelines will be held as the standard of care in any malpractice litigation. However, independent professional judgment must apply in clinical practice. All health care professionals are unconditionally responsible for their own treatment decisions. Disagreement between physician and dentist regarding the need for premedication may be due to one of two situations: the physician may be aware of the patient’s medical conditions of which the dental professional is unaware or the physician may not be aware of the new AHA guidelines. If the physician and dental professional disagree regarding recommendations, informed consent must be obtained and documented following a thorough discussion with the patient of the risks and benefits of all treatment options. Then the practitioner is protected from legal liability as long as the treatment is within the standard of care. All discussions with the patient and physician must be well-documented.4 The dental hygienist has the great responsibility of monitoring the patient’s health in the dental practice. These guidelines should be kept in the office as reference.

REFERENCES

- Wilkins EM. Clinical Practice of the Dental Hygienist. 9th ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2005.

- Wilson W, Taubert KA, Gewitz M, et al. Prevention of infective endocarditis: guidelines from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2007;116:1736-1754.

- Medline Plus Medical Encyclopedia: Infectious Endocarditis. Available at: www.nlm.nih.gov/medlineplus/ency/article/000681.htm. Accessed September 18, 2008.

- Infective Endocarditis. Available at: www.ada.org/prof/resources/topics/infective_endocarditis.asp. Accessed September 18, 2008.

- Wilson W, Taubert KA, Gewitz M, et al. Prevention of infective endocarditis: guidelines from the American Heart Association. J Am Dent Assoc. 2007;138;6:739-760.

- Lockhart PB, Loven B, Brennan MT, Fox PC. The evidence base for the efficacy of antibiotic prophylaxis in dental practice. J Am Dent Assoc. 2007;138:458-474.

- Tomas Carmona I, Diz Dios P, Scully C. Efficacy of antibiotic prophylactic Regimens for the prevention of bacterial endocarditis of oral origin. J Dent Res. 2007;86:1142-1159.

From Dimensions of Dental Hygiene. October 2008; 6(10):18-19.