SUNSTAR Spotlight: Prevent Early Childhood Caries

Through risk assessment and effective prevention protocols, the rising prevalence of this aggressive disease process can be stemmed.

Introduction

Manager, Professional Relations Sunstar Americas Inc

One of the most difficult appointments faced by dental professionals is when a young child sits in the chair and opens his or her mouth for approval, and sadly, the exam reveals severe decay and multiple abscesses.

To help prevent early childhood caries, the American Dental Association and the American Academy of Pediatric Dentistry have been promoting the establishment of a dental home for all children by their first birthday. During these appointments, parents are educated about the necessity of a quality oral hygiene routine, the benefits of systemic and topical fluoride use, and the hazards of consuming juices and sugar.

This issue of Sunstar Spotlight provides additional information and recommendations to support solutions for caries prevention for our youngest and most vulnerable patients. Through aggressive actions, we can make a difference in the fight against early childhood caries.

Early childhood caries (ECC) is an aggressive disease process that can result in severe destruction of the primary dentition. Children with ECC may experience pain and tooth loss that can impair sleep, normal growth, and school performance.1,2 By implementing early caries risk assessment and prevention protocols, we can decrease children’s caries experience and greatly improve their quality of life.

Historically, dental caries in young children was often described as, “baby bottle tooth decay” or “nursing bottle caries.”3 Over time, our understanding of this condition process has improved. We now recognize that many factors besides bottle use may contribute to a child’s caries experience. Thus, children younger than 6 who develop any decay are now referred to as having ECC.4

According to recent reports from the United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, more than one quarter of all 2- to 6-year-old children in the US (27.9%) have experienced decay, and nearly three-quarters of these children (73.4%) have unrepaired teeth.5 This amounts to 4.5 million affected toddlers, of which 3 million need restorative care before kindergarten. Even more alarming is the fact that ECC is on the rise. Over the past 20 years, while many Americans have experienced improved oral status, the prevalence of caries in children age 2–6 has actually increased.6 Figure 1 through Figure 3 illustrate the varying levels of decay experienced in young children.

RISK ASSESSMENT

Nearly all children start life with healthy primary teeth, yet within just a few years some develop ECC. The interplay of behavioral, environmental, and biologic factors determines which children will develop decay.7 Thus, by assessing these factors, we can determine each individual’s risk for developing ECC and direct prevention to those who need it most. Diet, oral hygiene, socioeconomic status, special health care needs, family, and bacteria are just a few factors that are effective in predicting risk.

Children who drink from a bottle containing sweet liquids after age 1, those who fall asleep while feeding, and those who frequently consume sugary foods are at high risk. Young children who brush their own teeth, do not brush before bedtime, and who exhibit visible plaque, also consistently experience higher levels of decay. Sociocultural factors have also been linked to ECC. Children whose parents have limited education, those who come from large families, and certain ethnic groups may be at increased risk. Parents who have children with special health care needs are also more likely to report that their children experience unmet dental needs. Higher levels of decay may be associated with premature birth, gastroesophageal reflux disease, asthma, radiotherapy and chemotherapy, and medication use. Children who have family members with decay are also at high risk. Each child acquires a unique oral flora during the early years of life. Most children acquire these bacteria from their mother. Thus, when mothers have high levels of pathogenic oral bacteria, their infants also tend to experience increased amounts of oral bacteria, increasing their risk of decay.8

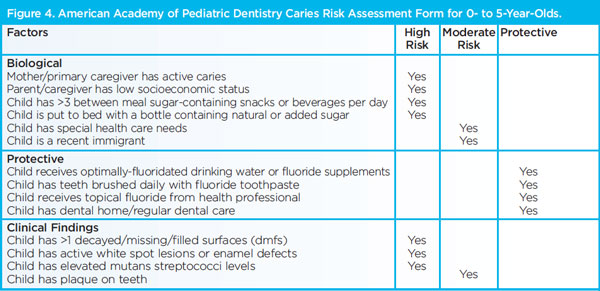

With so many factors to consider, assessing a child’s risk may seem like a daunting task. To help address this challenge, the American Academy of Pediatric Dentistry (AAPD) and the American Dental Association (ADA) have published caries risk assessment tools. These tools can be used in the clinic setting to quickly identify children at high risk of decay (Figure 4).

Circling those conditions that apply to a specific patient helps the practitioner and parent understand the factors that contribute to or protect from caries. Risk assessment categorization of low, moderate, or high is based on preponderance of factors for the individual. However, clinical judgment may justify the use of one factor (eg, frequent exposure to sugar-containing snacks or beverages, more than one dmfs) in determining overall risk.

PREVENTION PROTOCOLS

Implementation of an individualized prevention protocol is critical for children at moderate or high risk of developing ECC. This protocol may include modification of recare frequency, oral hygiene improvement, nutritional guidance, and increased fluoride exposure. Antimicrobial agents may also be employed to reduce the levels of pathogenic oral bacteria and decrease caries risk.

Preventive recare examinations are an important component of the caries management protocol. These visits allow the practitioner to evaluate the patient’s risk and disease progression. They also provide an important opportunity to strengthen the relationship between the patient and provider. Because many of the factors that contribute to ECC are behavioral, maintaining a positive relationship is critical to achieving treatment goals. Preventive visits for pregnant women, young parents, and children should include a discussion of the disease process and factors that increase caries risk. When presenting alternatives to these high-risk behaviors, caregivers should be offered a menu of preventive options. From this menu, they can select the options that are most appropriate for their child and lifestyle. If individuals take part in the decision-making process, the chances of achieving success may be greater than if they are simply told what to do.9 Increasing the frequency of recare visits to intervals, such as every 3 months, ensures additional time to discuss challenges that caregivers may be experiencing and opportunities to provide professional preventive therapies.10

During the recare visit, clinicians should also assess the child’s hygiene. Children with visible plaque are at much higher risk of developing ECC.11 Caregivers should be taught correct brushing technique and instructed to brush the child’s teeth twice daily with a fluoride dentifrice.

Moderate and high risk children younger than 2 should receive a smear (0.1 mg) of fluoride toothpaste twice a day. Children age 2 and older may receive a pea-sized amount of fluoride toothpaste (0.2 mg).12,13 Providing self-care instructions and brushing with a fluoride dentifrice decrease caries experience considerably in this age group.12,14

Caregivers should also be counseled on the frequency of sugared foods and beverage consumption. Dietary practices play a critical role in the process. Parents may not be aware that the frequency of their child’s carbohydrate consumption is more important than the types of foods consumed. Young children should not be expected to go without meals and snacks, however, snacking should be limited to defined periods and sweet beverages should be eliminated from bottles and sippy cups. Breaks provided in between meals and snacks will also allow for remineralization of the tooth structures that are weakened by dietary acid challenges.15

Fluoride therapy should be a cornerstone of any prevention program. Fluoride varnish provides higher overall caries reduction than other topical fluoride products, and it may be the most preferable method of fluoride application.16 According to ADA recommendations on fluoride therapy, children at moderate caries risk should receive professional fluoride twice annually, and those at high caries risk may benefit from applications up to four times a year.17

ANTIMICROBIALS

Children at high caries risk may also benefit from the application of antimicrobial agents. Dental caries is caused by bacteria, thus, decreasing the oral bacterial load may reduce disease experience. Xylitol, chlorhexidine, and povidone iodine are widely available and have been shown to reduce caries.

Xylitol is a non-nutritive sweetener that is available in a number of over-the-counter products, including foods, syrups, candies, and chewing gum. Research indicates that xylitol is effective when 4 g to 10 g are consumed each day, divided into three to seven consumption periods.18 Because young children typically acquire Streptococcus mutans from their mothers, it may be most effective to decrease transfer of these pathogenic bacteria through maternal xylitol use. In one study, a 70% caries reduction was seen in 6-year-olds whose mothers chewed xylitol gum when compared to those who had received chlorhexidine rinse and fluoride varnish.19

Chlorhexidine gluconate (CHX) is the antimicrobial gold standard for plaque and gingivitis control. The anticaries effects of CHX rinses, gels, and varnish have been investigated in research. Initially early findings seemed to indicate that CHX was very effective when used for caries control, however, recent analysis indicates that the caries-preventive effect of CHX products is limited (10% to 26%). Because of contradicting evidence, CHX rinses should not be recommended for primary caries prevention. The evidence for gels and varnishes is mixed, and they may prove effective for individual patients.20 Povidone iodine topical application is an antimicrobial used widely in medicine as a surgical scrub, skin disinfectant, and wound treatment. When used orally, it also suppresses S. mutans counts for at least 90 days.21 Children treated with povidone iodine showed nearly 50% lower development of white spot caries lesions over a 12-month period.22 Findings seem to indicate that this agent has a strong potential for prevention and treatment of early childhood caries, yet additional research is warranted before it can be recommended conclusively. Caution must also be exercised with patients who have a known allergy or sensitivity to iodine.

TREATMENT STRATEGIES

When preventive efforts fail to arrest ECC, treatment is indicated. The majority of restorative treatments used to repair pediatric dental decay are relatively simple, yet delivering high-quality care to young children can be quite challenging. This is not due to the technical procedures that are rendered, but rather because they must be performed on a young patient. In some situations where restoration is not possible or desirable, aggressive preventive measures may be implemented to limit decay progression.

This can provide time for the child to mature and develop the coping mechanisms needed for dental treatment. In many cases, however, restorative care must be provided in order to prevent or alleviate pain and tooth loss caused by dental decay. When invasive dental treatments are planned for young children, advanced behavior guidance, such as sedation and general anesthesia, is often required to facilitate the delivery of high-quality dental care. These techniques are very effective, but they require extensive resources and pose increased patient risk. Ultimately, sedation and general anesthesia have a place in pediatric dentistry, however by preventing ECC, the number of cases in which they must be used can be reduced.

CONCLUSION

ECC is a disease process that affects young children and can cause severe complications arising from pain and tooth loss. Clinicians should discuss this disease process with parents of young children and assess each patient’s risk for developing the disease. By implementing aggressive preventive efforts in patients who are at moderate to high risk, it is possible to reduce disease in young children and decrease reliance on advanced behavior guidance techniques such as sedation and general anesthesia.

REFERENCES

- Edelstein B, Vargas C, Candelaria D, Vemuri M. Experience and policy implications of children presenting with dental emergencies to US pediatric dentistry training programs. Pediatr Dent. 2006;28:431–437.

- Sheiham A. Dental caries affects body weight, growth and quality of life in pre-schoolchildren. Br Dent J. 2006;625–626.

- Berg J, Slayton R. Early Childhood Oral Health. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley-Blackwell;2009:31–45.

- American Academy on Pediatric Dentistry Council on Clinical Affairs. Policy on early childhood caries (ECC): unique challenges and treatment option. Pediatr Dent. 2008;30(Suppl):44–46.

- Dye BA, Tan S, Smith V, et al. Trends in oral health status: United States, 1988-1994 and1999-2004. Vital Health Stat 11. 2007:1–92.

- Kaste LM, Drury TF, Horowitz AM, Beltran E. An evaluation of NHANES III estimates ofearly childhood caries. J Public Health Dent. 1999;59:198–200.

- Beck JD. Risk revisited. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 1998;26:220–225.

- Berkowitz RJ. Causes, treatment and prevention of early childhood caries: a microbiologic perspective. J Can Dent Assoc. 2003;69:304–307.

- Ramos-Gomez FJ, Crall J, Gansky SA, Slayton RL, Featherstone JD. Caries risk assessment appropriate for the age 1 visit (infants and toddlers). J Calif Dent Assoc. 2007;35:687–702.

- Tinanoff N, Douglass JM. Clinical decision-making for caries management in primary teeth. J Dent Educ. 2001;65:1133–1142.

- American Dental Association. Caries Risk Assessment Form (Age 0-6). Available at:www.ada.org/sections/professionalResources/pdfs/topics_caries_under6.pdf. AccessedDecember 7, 2012.

- Lindhe J, Axelsson P, Tollskog G. Effect of proper oral hygiene on gingivitis and dental caries in Swedish schoolchildren. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 1975;3:150—155.

- American Academy of Pediatric Dentistry reference manual 2011-2012. Pediatr Dent.2011;33:1–349.

- Plutzer K, Spencer AJ. Efficacy of an oral health promotion intervention in the prevention of early childhood caries. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol.2008;36:335–346.

- Tinanoff N, Palmer CA. Dietary determinants of dental caries and dietary recommendations for preschool children. J Public Health Dent. 2000;60:197–206.

- Adair SM. Evidence-based use of fluoride in contemporary pediatric dental practice. Pediatr Dent. 2006;28:133–142.

- American Dental Association Council on Scientific Affairs. Professionally applied topical fluoride: evidence-based clinical recommendations. J Am Dent Assoc. 2006;1151–1159.

- American Academy on Pediatric Dentistry Council on Clinical Affairs. Policy on the use of xylitol in caries prevention. Pediatr Dent. 2008;30(Suppl):36–37.

- Isokangas P, Soderling E, Pienihakkinen K, Alanen P. Occurrence of dental decay in children after maternal consumption of xylitol chewing gum, a follow-up from 0 to 5years of age. J Dent Res. 2000;79:1885–1889.

- Twetman S. Treatment protocols: nonfluoride management of the caries disease process and available diagnostics. Dent Clin North Am. 2010;54:527–540.

- Zhan L, Featherstone JD, Gansky SA, et al. Antibacterial treatment needed for severe early childhood caries. J Public Health Dent. 2006;66:174–179.

- Lopez L, Berkowitz R, Spiekerman C, Weinstein P. Topical antimicrobial therapy in the prevention of early childhood caries: a follow-up report. Pediatr Dent. 2002;24:204–206.

From Dimensions of Dental Hygiene. January 2013; 11(1): 19–22.