Oral Health Begins with Tooth Alignment

Treating malocclusion and misaligned teeth can positively affect patients’ long-term oral health. This CE activity explains how and why.

This course was published in the April 2011 issue and expires April 2014. The author has no commercial conflicts of interest to disclose. This 2 credit hour self-study activity is electronically mediated.

EDUCATIONAL OBJECTIVES

After reading this course, the participant should be able to:

- Explain the effects of esthetic innovations in orthodontic treatment.

- Review the oral health dangers inherent in maloccluded teeth.

- Discuss the potential negative effects of occlusal trauma and misaligned teeth on oral structures and oral health.

- Identify the occlusal components of a patient examination.

- Describe the factors necessary for effective counseling of patients about occlusal treatment.

This course was developed in part with an unrestricted educational grant from Align Technology Inc.

Orthodontics is often thought of as an esthetic specialty. While providing a beautiful smile is one of the goals of orthodontics, a growing body of evidence shows that aligning the teeth to ensure pressure is distributed evenly and eliminating occlusal trauma are also beneficial to patients’ long-term oral health.1-4

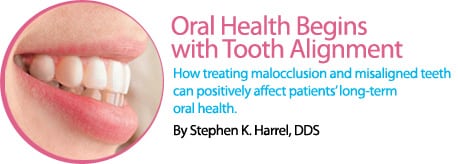

Improved oral health has always been one of orthodontic therapy’s goals. Until the advent of adult orthodontics, traditional orthodontics used the growth patterns of children to help guide the teeth into the desired position for function and esthetics. This often involved the extraction of teeth to create room for tooth movement and moving the teeth so they followed the predicted growth pattern of the jaw. The orthodontic movement of the teeth was usually accomplished by affixing brackets to the teeth and using custom, hand-bent wires to guide the teeth to the desired position (Figure 1). Over the past several decades, adult orthodontic therapy has increased in popularity. This fact has changed the way orthodontic therapy is planned and performed because adult orthodontic therapy must work within relatively fixed skeletal relationships.

NEWER METHODS OF ORTHODONTIC THERAPY

Innovations in orthodontic therapy have greatly improved patient acceptance. Gone are the days of “metal mouth.” The esthetic revolution within orthodontics has made the therapies much more appealing to adult patients. Aligner technology, which uses computer-generated removable positioning devices to move teeth into the desired position, is one of these esthetic advances (Figure 2). The movement is often aided by minor reshaping of the teeth to allow adequate room for realignment. This newer technology is less invasive, is not necessarily based on growth and maturation of the patient, and enables minor tooth movement more quickly and easily than traditional approaches.5-7 Since its introduction a decade ago, aligner technology has grown significantly in popularity with both patients and practitioners.

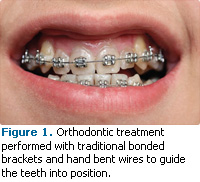

Ceramic brackets made of clear or tooth-colored material provide the same treatment results as metal brackets, but with a more esthetic appearance (Figure 3). The clear, tooth-colored, or brightly-colored (for children) brackets are sealed on with a plasma light and strong adhesive. However, they are contraindicated for patients with deep overbites or other significant jaw problems.8 Lingual braces are another esthetic innovation. They are placed on the lingual surfaces of the teeth so they are essentially not visible to others (Figure 4). Lingual braces are an esthetic option for adults and teenagers and require an orthodontist with expertise in this technique.9,10 Patients may experience speech problems and have difficulty chewing with lingual braces.9,10

Oral health conditions that in the past might have been considered too difficult, invasive, or time consuming to treat can now be addressed relatively easily with orthodontic treatment.1-7 As a result, the parameters of orthodontic therapy need to expand to include the evaluation and diagnosis of specific health concerns that can be treated with orthodontics.

ADEQUATE ORAL HYGIENE

Due to access problems, difficulty in performing adequate oral hygiene is one of the major disadvantages experienced by patients with malocclusion or malpositioned teeth. Examples include teeth that cross over each other, such as in crowded mandibular anteriors; teeth that are in severe buccal or lingual version (teeth angled toward the buccal or lingual); and teeth that are tilted in so the marginal ridges are uneven and interproximal contact points are inadequate in preventing food impaction.

|

|

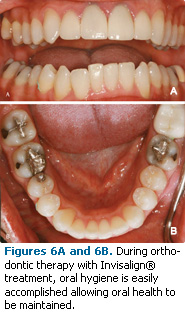

Crowding of the teeth can make it difficult to perform effective interproximal oral hygiene (Figures 5-6). This type of crowding also tends to make adequate brushing and flossing difficult, which encourages the formation of calculus.

The treatment of tooth crowding can be accomplished with both traditional brackets and wires or aligner technology. In many cases where the crowding and associated oral hygiene problems are considered relatively minor or moderate, practitioners may be hesitant to recommend orthodontic therapy because of the difficulty in using brackets and wires, which can include reduced esthetics, presence of pain, long treatment times, and the increased risk of decay. With the advent of aligner technology, many of these moderately malpositioned teeth can be easily corrected with orthodontics.

OCCLUSAL TRAUMA

Occlusal trauma to the periodontium is most often described as an injury to the supporting tissue and can only be definitively diagnosed by viewing the periodontal supporting structures as histologic specimens. This level of diagnosis is clearly impractical for the clinical evaluation of functional teeth. Therefore, the clinical definition of occlusal trauma is generally defined as heavy contact between teeth that can result in clinical detectable changes in periodontal tooth support or tooth anatomy.

The most frequently detected change resulting from occlusal trauma is an increase in the mobility of the teeth. This can be caused by primary occlusal trauma or excessive force placed on a healthy tooth with intact periodontal support. A classic example of primary occlusal trauma is a newly placed restoration that has not been properly occlusally adjusted resulting in “high” occlusion. This excessive occlusal contact will lead to increased mobility and often to increased pain and dentin hypersensitivity. The onset of these symptoms usually occurs within hours or days of the restoration being placed. The symptoms can usually be quickly relieved with proper adjustment of the occlusal contacts and they typically do not lead to long-term damage of the periodontium.

|

|

Another type of occlusal trauma that affects the periodontium is secondary occlusal trauma, which is defined as a normal occlusal force placed on a weakened periodontal supporting structure. This type of occlusal trauma is often seen in patients who have moderate to advanced periodontal destruction. Usually the amount of bone supporting the tooth has been diminished by periodontal bone loss and the tooth slowly becomes mobile. Patients with secondary occlusal trauma need to have their periodontal inflammation addressed and their occlusal trauma initially treated with selective grinding of the occlusal surfaces with the possibility of regenerative periodontal therapy to provide adequate bone support. Orthodontic therapy can, in some cases, be considered where the teeth are repositioned in a more favorable position for distributing occlusal stress.

In both primary and secondary occlusal trauma, the periodontium will benefit from correcting occlusal discrepancies and minimizing occlusal trauma. This can be accomplished, in some cases, with the adjustment of the occlusal surfaces by selective grinding of the cusp tips and the fossas of the occlusal surfaces of the teeth. Orthodontic movement of the teeth is extremely beneficial in accomplishing the necessary improvements in occlusal relationships. The selective grinding of the occlusal surfaces of the teeth is often an important part of orthodontic therapy, both during active therapy and at the completion of orthodontic therapy.

EFFECT OF OCCLUSAL TRAUMA ON THE PERIODONTIUM

Occlusal trauma has long been associated with increased periodontal pocket depths and periodontal attachment loss. However, animal-based studies show that occlusal trauma does not directly cause periodontal destruction.11,12 These studies disproved earlier theories that periodontal diseases were initiated by occlusal trauma. Periodontal diseases can be caused by a bacterial insult to the periodontal supporting tissues and the patient’s immunologic response to the bacterial insult. However, occlusal trauma is a significant risk factor for increased periodontal pockets and bone loss in patients with periodontal diseases. Recent research shows that occlusal trauma is an equal or greater risk factor for the progression of an existing periodontal disease as the traditional risk factors of smoking or poor oral hygiene.13 The diagnosis and treatment of occlusal trauma are also important parts of the successful treatment of periodontal diseases.

The use of orthodontic treatment can be part of the correction of malocclusion and the mitigation of continued periodontal breakdown. In almost all cases, some amount of selective grinding of the occlusal surface in addition to orthodontically correcting the misalignment of the teeth will be necessary. The combination of orthodontics and selective grinding can lead to near ideal occlusal relationships that previously could only be accomplished with extensive full coverage restorations (full mouth rehabilitation).

EFFECT OF OCCLUSAL TRAUMA ON TEETH

Occlusal trauma can directly damage the teeth even when periodontal breakdown is not present. Some wearing of the occlusal surfaces is most likely a natural part of the aging process. However, teeth that are misaligned and undergoing occlusal trauma will often show excessive occlusal wear. When a significant portion of the occlusal surface has worn away, changes will occur in skeletal relationships between the jaws that may lead to soreness and trauma in the temporomandibular joint. Additionally, excessive wear can cause esthetic concerns, closing of the vertical dimension, changing of the interproximal contacts leading to food impaction, an eventually exposure of the dentin with resulting pulpal pain and decay.

Occlusal wear should be evaluated at all examination visits, and if significant wear is present, orthodontic treatment should be considered. While excessive wear is often associated with parafunctional habits, such as bruxing, isolated wear of individual teeth may be related to orthodontically treatable misalignment of the teeth. At the completion of orthodontic therapy, retainer appliances should be recommended to also function as occlusal guards to minimize further wear from nocturnal bruxism.

There is evidence that fractures of the teeth, and especially root fractures are associated with occlusal trauma.14 Tooth fracture may be associated with excessive wear on the teeth but wear patterns should not be solely relied on for the diagnosis of excessive forces on the teeth. A large percentage of the teeth lost in older adults is associated with tooth/root fracture rather than decay or periodontal diseases.15 Correcting the alignment of the teeth will distribute the stress during bruxism to be spread over more teeth and, while not proven, may decrease the possibility of tooth/root fracture.

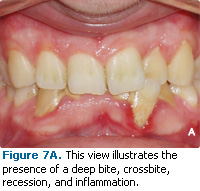

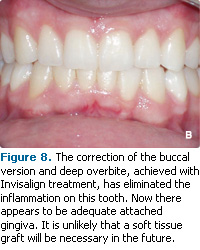

GINGIVAL RECESSION

There is a strong correlation between misaligned teeth and gingival recession.16,17 Recession on misaligned teeth is usually associated with teeth that are tilted to the buccal or lingual (buccal or lingual version). The mechanism for this recession is unknown but may be caused by misalignment of teeth stretching the gingival tissue, making it more susceptible to trauma. The only treatment available for teeth with this type of misalignment is orthodontic therapy. Selective grinding of the teeth (occlusal adjustment) or occlusal guard therapy are unlikely to benefit these patients. Interceptive or preventive orthodontic therapy for patients with this type of misalignment may prevent the need for future soft tissue grafting or even the loss of these teeth (Figures 7-8).

Gingival recession may be associated with direct occlusal trauma, such as excessive occlusal pressure on the teeth. However, research does not support this correlation.12,13 The only factor thatis routinely associated with gingival recession is the misalignment of teeth. Therefore, orthodontic therapy is strongly indicated when this type of misalignment exists.

|

|

ABFRACTION

Abfraction is the loss of tooth material due to the stretching and fracturing of the crystalline structures of the teeth caused by excessive occlusal forces. The lesion of abfraction is an erosion, most frequently on the facial/buccal surface of the tooth at the cemental enamel junction (CEJ). Because the elasticity of enamel and dentin is different, the occlusal flexing of the tooth in a buccal-lingual direction may fracture the hard and brittle crystalline structure of enamel, which may cause the formation of a V-shaped lesion at the CEJ.

Whether an abfraction lesion is due to an occlusal mechanism or the result of wearing and dissolving of the tooth structure (ie, from toothbrush abrasion and the use of abrasive toothpastes) is controversial. If abfraction is caused by occlusal trauma, then orthodontic treatment, occlusal adjustment, and possibly the use of a bruxism appliance are indicated for the treatment and prevention of abfraction lesions.

TEMPOROMANDIBULAR JOINT PAIN AND DYSFUNCTION

The role of occlusion and misalignment of the teeth in temporomandibular joint (TMJ) pain and dysfunction is another controversial area. One school of thought states that occlusion is a major cause of TMJ pain and dysfunction, while another believes that occlusion has little to do with TMJ symptoms. TMJ symptoms have long been associated with occlusal dysfunction, and treatment of occlusal disharmonies can result in a decrease in TMJ symptoms.

The occlusion of patients suffering from TMJ symptoms should be evaluated for significant occlusal trauma and the misalignment of teeth. If these are present, occlusal treatment, including orthodontic correction, should be considered. Treatment for patients with active TMJ symptoms should be approached with caution in order to ensure that any treatment of occlusal trauma or orthodontic therapy does not worsen their TMJ symptoms. If possible, the TMJ symptoms should be ameliorated first followed by occlusal or orthodontic treatment.

PATIENT EXAMINATION

An evaluation of tooth position, tooth contacts, and signs of damage from occlusal trauma should be part of every routine evaluation. Patients should be informed that misaligned teeth can pose both long-term and short-term risks to their oral health. For example, patients with mandibular cuspids that are tilted to the buccal (buccal version) should be warned that this type of malocclusion/ misalignment is associated with gingival recession. Patients need to understand that that orthodontic treatment usually minimizes the risk of future soft tissue grafting, and that the labial or buccal tilt of these teeth may worsen with age.

Other patients at risk have posterior teeth that are tilted to the mesial. This misalignment, sometimes referred to as posterior bite collapse, often results in food being stuck between the teeth due to inadequate interproximal contacts. Food impaction and the resultant gingival trauma are common problems for many patients, and dental professionals need to discuss the option of orthodontic therapy as a solution. Orthodontic treatment should be compared to the more invasive restorative solution where restorations or full coverage crowns are placed to restore the inadequate interproximal contacts. Without any treatment, periodontal degeneration may result due to trauma caused by food impaction.

Observed signs and conditions should be evaluated and entered into the chart, including misaligned or tilted teeth, wear facets or wear patterns on the teeth, fracture lines on the teeth (especially those associated with wear patterns), noise or shifting in the TMJ when the patient opens his or her mouth, increased mobility of the teeth, or heavy contact on isolated teeth. The evaluation of these signs of occlusal trauma are straightforward and take only a brief time to perform but are often not routine parts of periodic examinations. When any of these features are noted, patients should be counseled on the potential damage these signs represent in addition to their options for correcting these problems with orthodontic therapy.

One of the most frequently overlooked occlusal findings is the evaluation of discrepancies or occlusal contacts in centric relationship. Centric relation is a position of the mandibular condyles in the deepest part of the glynoid fossa (ie, the head of mandible is in the deepest part of the TMJ). This position is considered neutral for the TMJ and is achieved by gentle manipulation of the mandible with both of the clinician’s hands, putting pressure on the chin area in a rearward and upward position. Once in this position, patients are asked to slowly close their jaws until their teeth first contact.

The initial contact(s) is called the centric contact. This contact may occur at the same time on most teeth, which is normal. However, there is often contact on only one or two teeth in the centric position and then there is a slide to where most of the teeth contact (maximum intercuspation or centric occlusion). This is called a “slide in centric” or a centric relation to centric occlusion (CR to CO) shift. The presence of this slide is associated with deepening pocket depth, increased periodontal attachment loss, and increased periodontal degeneration in patients with periodontal diseases.13 The greater the slide between these two positions, the greater the damage to the periodontium.13

The correction of this slide is an important part of successful periodontal treatment but it is frequently overlooked. If the teeth are in relatively good alignment, this slide can be treated with selective grinding of the occlusal surfaces (occlusal adjustment) but if it is caused by misalignment of the teeth, orthodontic therapy in combination with occlusal adjustment is warranted.

Dental professionals need to add the evaluation of these occlusally-related findings to their routine examinations. Because occlusal examinations are not routinely performed, occlusal trauma is one of the most under-treated oral conditions. Dental hygienists are in the unique position to make this information part of patients’ records and discuss various treatment options as well as the risks of not treating these conditions.

COUNSELING THE PATIENT ON OCCLUSAL TREATMENT

Patients are often resistant to dental treatment if they are not in pain. Occlusal problems rarely cause pain until they reach an advanced stage. Occlusal-related problems that can cause pain include TMJ pain, primary occlusal trauma, advanced periodontal pockets, fractured teeth, and gingival recession that has progressed through the attached gingiva into the gingival mucosa. The occlusal etiology of most of these painful episodes has usually been present for an extended period, often years, before symptoms emerge. The goal of patient counseling is to recommend effective treatment for these problems before they become painful, require extensive treatment, or cause tooth loss.

In discussing occlusal treatment and its contribution to improved oral health, the esthetic advantages of orthodontic treatment should also be included, as this factor can be a powerful incentive for patient acceptance. The existence of newer methods of orthodontic treatment is also a considerable incentive, particularly among adults. In discussing occlusal treatment and its contribution to improved oral health, the advantages of orthodontic treatment should also be included. Patients may be resistant to orthodontic treatment for a variety of reasons. See Table 1 for a list of common reasons why patients refuse orthodontic therapy.18,19 The new esthetic options available in orthodontic treatment, as well as the long-term esthetic benefits to the smile can be powerful incentives for patient acceptance, particularly among adults. A Swedish study that looked at adult perceptions of oral health care decisions made when they were children and adolescents found that the advice of dental professionals had the greatest impact on their decision to choose orthodontic treatment.20 Study participants with malocclusion and other orthodontic needs who had declined orthodontic therapy as adolescents were the least satisfied with their current oral health status.20 Effective communication about orthodontic therapy and treatment options in patients with malocclusion is paramount to comprehensive oral health care.

CONCLUSION

Dental hygienists are trusted sources for advice on long-term oral health, which puts them in the perfect position to discuss orthodontic treatment options. Dental hygienists should make occlusal and tooth position analysis a routine part of their examinations in addition to patient counseling about treatment options, including orthodontics.

Figure 4 © MENDIL / BSIP / PHOTO RESEARCHERS, INC.

Figures 5-6 courtesy of Steven Glassman, DDS, Glassman Dental Care, New York.

Figures 7-8 courtesy of Benedict Miraglia, DDS, Mount Kisco, NY.

REFERENCES

- Nunn ME, Harrel SK. The effect of occlusal discrepancies on periodontitis. I. Relationship of initial occlusal discrepancies to initial clinical parameters. J Periodontol. 2001;72:485-494.

- Nunn M, Harrel SK. The effect of occlusal discrepancies on periodontitis: I. Relationship of initial occlusal discrepancies to initial clinical parameters. J Periodontol. 2001;72:495-505.

- Harrel SK, Nunn ME. The effect of occlusal discrepancies on gingival width. J Periodontol. 2004;75:98-105.

- Harrel SK. Occlusal forces as a risk factor for periodontal disease. Periodontol 2000. 2003;32:111-117.

- Kravitz ND, Kusnoto B, BeGole E, Obrez A, Agran B. How well does Invisalign work? A prospective clinical study evaluating the efficacy of tooth movement with invisalign. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2009;135:27-35.

- Boyd RL. Esthetic orthodontic treatment using the Invisalign appliance for moderate to complex malocclusion. J Dent Educ. 2008;72:948-967.

- Kravitz ND, Kusnoto B, Agran B, Viana G. Influence of attachments and interproximal reduction on the accuracy of canine rotation with Invisalign. A prospective clinical study. Angle Orthod. 2008;78:682-687.

- Bishara SE, Fehr DE. Ceramic brackets: something old, something new, a review. Semin Orthod. 1997;3:178-188.

- Shum LM, Wong RW, Hägg U. Lingual orthodontics—a review. Hong Kong Dental Journal. 2004;1:13-20.

- Gilbert A. Lingual Orthodontics: the Truly Invisible Orthodontics. Juarez, Mexico: Trillas; 2008.

- Polson A, Kennedy J, Zander H. Trauma and progression of periodontitis in squirrel monkeys. I. Co-destructive factors of periodontitis and thermally produced injury. J Dent Res. 1974;9:100-107.

- Lindhe J, Svanberg G. Influence of trauma from occlusion on the progression of experimental periodontitis in the beagle dog. J Clin Perio. 1974;1:3-14.

- Harrel SK, Nunn ME. The association of occlusal contacts with the presence of increased periodontal probing depth. J Clin Perio. 2009;36:1035-1042.

- Brynjulfsen A, Fristad I, Grevstad T, Hals-Kvinnsland I. Incompletely fractured teeth associated with diffuse longstanding orofacial pain: diagnosis and treatment outcome. Int Endod J. 2002;35:461-466.

- Chrysanthakopoulos NA. Reasons for extraction of permanent teeth in Greece: a five-year follow-up study. Int Dent J. 2011;61:19-24.

- Harrel SK, Nunn ME. The effect of occlusal discrepancies on gingival width. J Periodontol. 2004;75:98-105.

- Rodier P. Clinical research in the etiopathology of gingival recession. J Periodontol. 1990;9:227-234.

- Bengi AO, Karacay S, Akin E, Olmez H, Okçu KM, Mermut S. Use of zygomatic anchors during rapid canine distalization: a preliminary case report. Angle Orthod. 2006;76:137-147.

- Vlaskalic V. Occlusal trauma and adult orthodontics. In: Hall WB, ed. Critical Decisions in Periodontology. 4th ed. Hamilton, Ontario: BC Decker Inc; 2003:134-135.

- Bergström K, Halling A, Wilde B. Orthodontic care from patients’ perspective: perceptions of 27-year-olds. Eur J Orthod. 1998;20:319-329.

From Dimensions of Dental Hygiene. April 2011; 9(4): 64-71.