Occupational Health Hazards

Musculoskeletal injuries are common among dental professionals but they can be prevented.

This course was published in the September 2014 issue and September 30, 2017. The authors have no commercial conflicts of interest to disclose. This 2 credit hour self-study activity is electronically mediated.

EDUCATIONAL OBJECTIVES

After reading this course, the participant should be able to:

- Discuss the risk factors that predispose dental professionals to developing work-related musculoskeletal disorders.

- Identify working conditions that contribute to musculoskeletal disorders.

- Describe proper body alignment and neutral positioning.

Musculoskeletal disorders (MSDs) are occupational health hazards for dental hygienists. They contribute to lost work time, increase the need for health services and costs for medical care, and negatively impact overall quality of life. Dental professionals are at risk for developing MSDs due to the following: they perform the same tasks over and over, awkward posturing is often required to gain access to the oral cavity, and a high level of force is needed to perform tasks.1 While only 3% of MSDs reported to the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) are related to repetitive motion, these cases result in almost three times as many missed work days compared to other injuries.2 Other contributing factors for MSDs include: sitting in static or sustained positions, insufficient rest or breaks, exposure to vibrations and high pressures, poorly designed tools and workstations, improperly fitted equipment, and poor clinician fitness level.2

Injury Development

In health, the spinal column is designed to maintain an erect posture. Balanced posture helps ensure that muscular activity on the vertebral column is minimized and that weight is properly distributed. Maintaining muscular health depends on the ability of the body’s muscles, ligaments, tendons, and connective tissues to withstand a variety of stresses. When guidelines for proper body mechanics are not followed and awkward and/or prolonged static postures become habitual, the body will compensate to maintain posture. Ultimately, the muscular, vascular, and nervous systems are negatively affected.

The development of MSDs is not easily recognized, as there are no outwardly visible signs. The damage caused by MSDs is subtle. While the inflammatory response begins the healing process for injured connective tissues, the process tends to be delayed due to its reduced blood supply. Acute inflammation due to injury or muscular stress is easier to identify and treat. When and why the acute inflammatory response shifts to the chronic state is still not known, but the mechanism of action seems to be related to repetitive motions or excessive loading.3

How the tissues respond to stress determines their ability to withstand the force placed on a tissue. For example, when a joint is not moving, it has a static load. This load limits the oxygen supply to the area and hampers elimination of metabolic byproducts.4 When an individual strays from normal posture, as with excessive forward bending, the soft tissues recognize the new posture as different.5 Tissues can typically recoil from stress when it is short-lived; however, prolonged periods of stress and continuous strain to the same group of muscles overload the tissues, resulting in MSDs.6 When the body remains in prolonged postures, the following problems may occur: imbalances in the muscles, ischemia, trigger points, joint hypomobility, and spinal disk degeneration.6

Progressively prolonged static postures also lead to muscle ischemia/necrosis from impaired blood flow to the muscles.7 Physical signs of impaired blood flow include the development of trigger points, decreased range of motion, loss of flexibility, and pain. Improper loading can cause some muscles to stretch while opposing muscles undergo adaptive shortening, making it impossible for the muscles to return back to normal alignment.3,8

There are three categories in the assessment process of musculoskeletal change:?postural syndrome, dysfunction due to tissue change, and derangement.8,9 Postural syndromes are treated through recognition and subsequent postural adjustment/corrections. When the pain can be eliminated by simply changing positions, permanent damage has not occurred. For instance, if the finger is hyperextended for a prolonged period, eventually, pain will be felt. Correcting the posture by releasing the finger eliminates this pain.8,9

Dysfunction, the second category, is caused by tissue changes, and exercise intervention may be required. Dysfunction may result from trauma, inflammation, or adaptive shortening of muscles with symptoms of sporadic pain and/or limited movement. Trying to move an arm for the first time after being casted for an extended period illustrates the restricted movement and possible pain of the dysfunction category.

Derangement is the most serious category and is caused by tissue displacement. Characterized by constant pain, derangement may require professional intervention when recommended exercises do not eliminate the discomfort. The derangement level may ultimately lead to reducing work hours or leaving dental hygiene practice.

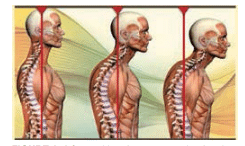

In addition to length of time in poor postures, the result of one bad postural habit is not always limited to the development of a MSD in the affected body part. For example, the forward head posture that may result from continuous neck flexion greater than 20° can produce a postural problem. The head’s center of gravity typically falls slightly forward to the ear.8 With each inch that the head falls from the center of gravity, additional load is placed on the cervical vertebra and related components. When the head is bent forward 2 inches toward the top portion of the sternum, 20 lbs is added to the load—10 lbs for the head and 10 lbs for the forward posture.

Prolonged forward flexion of the head can lead to muscle pain and fatigue in the upper trapezius, rhomboids, and levator scapulae. In addition, rounded shoulders and stretching and adaptive shortening of the muscles in the upper back and neck area may occur. In severe cases, derangement may result, leaving the individual unable to completely retract the head to a vertical position. In order for the individual to look up, he/she is only able to raise the eyes forward. This posture resembles a turtle posture; the head is raised up without having the neck erect (Figure 1). Ultimately, this posture can lead to joint pain in the temporomandibular joint.8 In addition to postural change, forward neck flexion of more than 30° can impair blood flow.10

Proper Alignment and Neutral Positions

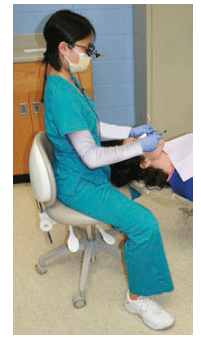

Early studies recommended positioning the clinician at the 9 o’clock or 12 o’clock position, placing the patient in the supine position, and sitting using a contoured dental chair to improve access to more areas of the mouth and facilitate movement around the dental chair.11–13 These recommendations supported improvements in clinician positioning, equipment, and workplace design, as well as set standards for ergonomics in dental hygiene. Today, dental hygienists are taught to use a variety of clock positions.

Following recommended neutral positions and maintaining acceptable degrees of movement while performing clinical procedures is key to maintaining proper alignment. The 11 o’clock to 1 o’clock working range is recommended because it helps clinicians maintain a neutral position.14 Ideally, the neck should not be flexed more than 15°, the back 20°, abduction of the upper arm not greater than 20°, and the forearm not greater than 60°. The shoulders should remain equal on a horizontal plane and the hand should be angled with the little finger in a downward tilt from the thumb (Figure 2).

Previously, the sitting position was taught so that the feet were flat on the floor, thighs at 90°, forearms parallel to the floor, and the spine perpendicular to the floor. New recommendations for the position of the thighs places the feet flat on the floor and thighs on a downward slant with a hip angle of 105° with a tilted seat base, or 125° with a saddle stool.14

New recommendations for dental lighting also exist. Previously, for the maxillary arch, the dental light was moved over the patient’s chest and then tilted upward toward the maxillary teeth. Now, it is recommended that the dental light follow the practitioner’s line of vision to within 15°; thus, the light is above and slightly behind, or depending on the clock position, to the side of the clinician’s head and tilted downward toward the patient’s oral cavity at the mid-sagittal plane.14–16 Placing the overhead light in the practitioner’s line of vision mimics the light attached to loupes.

These recommendations promote “ideal” positions; however, everyone is built differently. Each person’s ability to visualize and/or reach certain areas of the mouth may be difficult while still maintaining a neutral position. Sustaining this posture is additionally hampered by poor workstation design, the need for direct view of the oral cavity, and the belief that using one or two poor postures during an appointment will not have a long-lasting effect. Also, difficulty in maintaining acceptable postures increases as the day progresses and muscles become fatigued. Tired muscles encourage the body to slump.17–19 The earlier in the day that the clinician’s muscles become fatigued, the faster the poor posture will develop. Poor positioning behaviors tend to become habitual.

Other considerations include patient and equipment positioning. Clinicians frequently adjust their bodies to accommodate for improper positioning of the patient’s head. The practitioner’s spine typically follows the patient’s maxillary plane, so if the patient’s head is tilted downward, the clinician may lean forward excessively in order to see.15 To determine whether the patient is in the correct position, the clinician should look at the patient’s maxillary plane. The maxillary plane should be almost perpendicular to the floor to access most areas of the mouth. Accessing maxillary second and third molars may require the patient to tilt slightly backward, and to access the mandibular anterior teeth, the head may be tilted downward. It is better to adjust patients’ positioning than for clinicians to repeatedly strain their bodies to improve visual access.

Ergonomic Devices

Dental manufacturers have developed ergonomically designed products to prevent and/or minimize adverse effects associated with MSDs. These products include:

- Lightweight instruments with specialized grips and handle dimensions

- Loupes with and without lighting

- Ultrasonic handpieces that are cordless, lightweight, and balanced

- Handpieces that swivel

- Operator stools with tailored designs for improved support of the back and arms

When looking for an ergonomically designed piece of equipment, the clinician should ask:

- What is the purpose of the design?

- What is the equipment intended to do?

- How will using this equipment benefit me?

- Has the equipment item been thoroughly tested and researched?

- Does the manufacturer offer a trial period?15

Clinicians should test the equipment to see how it feels during actual use. The operator stool, which is used every day, should be tested before purchasing. Conventional stools should have adjustable seat pans and backrest support. Stools with armrests should have either moveable armrests or adjustable armrests. Saddle stools may or may not have a back support system, but allow the clinician’s pelvis to remain in a neutral position.14

Accessibility of equipment is also critical. Equipment used routinely, such as instruments, handpieces, and suction, should be within a 14-inch to 18-inch reach (about the length of fingertip to elbow).14 The workstation should enable clinicians to move freely around their patients. In addition, the dental chair should enable the patient to be placed in a supine position while still allowing for easy movement around the patient.

Additional Considerations

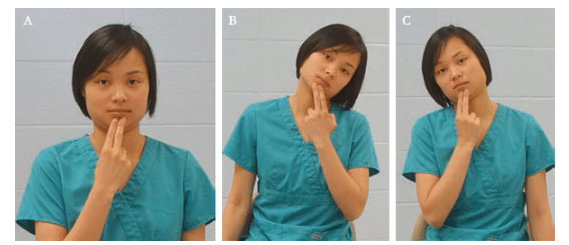

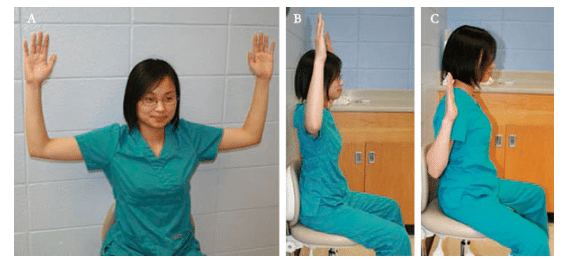

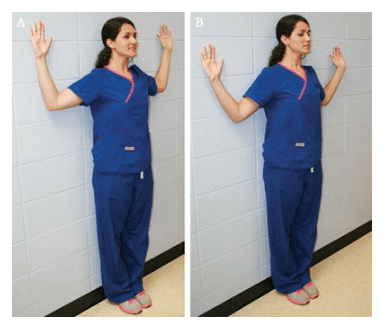

The body is meant to move. Although it is not possible to constantly move while working, clinicians should mix up the positional routine. They can easily stretch their arms when changing positions, retract their chins, or turn their heads to the side when reaching for an instrument. Also, practitioners can occasionally stand or perform a shoulder stretch in the doorway. Standing up periodically stimulates nerves, breaks up static postures, restores blood flow, and helps strengthen skeletal muscles. Clinicians should set a goal to stand up every 20 minutes to 25 minutes, or 30 times to 35 times a day.20 Exercises that can be performed in the office are illustrated in Figure 3 through Figure 5.

Conclusion

Dental professionals are at high risk for developing MSDs due to improper positioning and repetitive motions that can lead to permanent tissue injury and chronic pain and dysfunction. Clinicians should perform a self-evaluation to determine whether they are placing themselves at greater risk by failing to adopt and maintain neutral positions. Use of ergonomic equipment may be helpful in reducing muscle strain and fatigue. Implementing positive changes, including regularly stretching and standing up throughout the day, may help to minimize or eliminate MSDs. Maintaining good physical health is essential to practicing without pain, both of which contribute to improved quality of life.

Acknowledgement

The authors thank Elizabeth O. Carr, RDH, MS, for her assistance with the photography in this manuscript.

REFERENCES

- Wolny K. Shaw K, Verougstraete S. Repetitive strain injuries in dentistry. Ont Dent. 1999;76:13–19.

- United States Department of Labor. Nonfatal Occupational Injuries and Illnesses Requiring Days Away from Work, 2011. Available at: bls.gov/news.release/osh2.nr0.htm. Accessed August 15, 2014.

- Voight ML, Hoogenboom BJ, Prentice WE. Musculoskeletal Interventions: Techniques for Therapeutic Exercise. New York: McGraw Hill Medical; 2007.

- Kumar S. Biomechanics in Ergonomics. Philadelphia. Taylor and Francis; 1999.

- Barry RM, Woodall WR, Mahan JM. Postural changes in dental hygienists. Four year longitudinal study. J Dent Hyg. 1992;66:147–150.

- Valachi B, Valachi K. Mechanisms leading to musculoskeletal disorders in dentistry. J Am Dent Assoc. 2003;134:1344–1350.

- Valachi B. Move to improve your health: The research behind static postures. Dent Today. 2011;30:144–147.

- Dutton M. Orthopaedic Examination, Evaluation, and Intervention. New York: McGraw-Hill Medical Publishing Division; 2004.

- Donelson R. The McKenzie approach to evaluating and treating low back pain. Orthop Rev. 1990;19:681–686.

- Hagberg M. ABC of work related disorders. Neck and arm disorders. BMJ. 1996; 313:419–422.

- Golden SS. Human factors applied to study of dentist and patient in dental environment: A static appraisal. J Am Dent Assoc. 1959;59:17–28.

- Eccles JD, Davies MH. A study of operating positions in conservative dentistry. The Dental Practitioner and Dental Record. 1971;21(7):221–225.

- Robinson GE, Wuehrmann AH, Sinnett GM, McDevitt EJ. Four-handed dentistry: The whys and wherefores. J Am Dent Assoc. 1968;77(3):573–579.

- Valachi B. Practice Dentistry Pain-Free. Portland, Oregon: Posturedontics Press; 2008.

- Murphy DC. Ergonomics and the Dental Care Worker. Washington, DC: American Public Health Association; 1998.

- Occupational Health Clinics for Ontario Workers. Ergonomics and Dental Work. Available at: ohcow.on.ca/uploads/Resource/Workbooks/ ERGONOMICS%20AND%20DENTAL%20WORK.pdf. Accessed August 15, 2014.

- Liskiewicz ST, Kerschbaum WE. Cumulative trauma disorders: An ergonomic approach for prevention. J Dent Hyg. 1997;71:162–167.

- Greenfield B, Catlin PA, Coats PW, Green E, McDonald JJ, North C. Posture in patients with shoulder overuse injuries and healthy individuals. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 1995;21:287–295.

- Valachi B. Balancing your musculoskeletal health: Preventing and managing work-related neck pain. J Mass Dent Soc. 2006;55:24–26.

- Vernikos J. Sitting Kills, Moving Heals. Fresno, California: Quill Driver Books; 2011.

From Dimensions of Dental Hygiene. September 2014;12(9):58–61.