Not Just For Kids

The addition of sealants to your prevention protocol can help reduce the risk of caries among adult patients.

This course was published in the June 2011 issue and expires June 2014. The author has no commercial conflicts of interest to disclose. This 2 credit hour self-study activity is electronically mediated.

EDUCATIONAL OBJECTIVES

After reading this course, the participant should be able to:

- Discuss the differences between the application of fluoride and the placement of sealants.

- Explain how the placement of sealants in adult teeth with incipient caries may be beneficial in some aspects.

- Identify the dental hygienist’s role in improving dental sealant retention in adults.

- Detail the technique for the repair of sealants.

Dental sealants are typically indicated for children whose teeth are in the early stages of development. Little attention has been placed on the preventive long-term effects of using sealants in the adult permanent dentition. Yet, the application of dental sealants can reduce occlusal pit and fissure caries, ultimately improving the oral health of adult patients.

SEALANTS FALL BEHIND FLUORIDE

The introduction of sodium fluoride into American public water supplies in 1945 and fluoride’s broad incorporation into tablets, toothpastes, and mouthrinses have significantly impacted the prevention of dental caries.1 Sealant placement and the use of fluoride are the pinnacles of a highly effective caries prevention program.

While fluoride is a cornerstone of preventive treatment in the dental field, dental sealants remain underutilized. Data released by the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES III) revealed that less than 19% of American children from the ages of 5 years to 17 years have one sealed permanent tooth.2 The use of sealants among adults is even lower. The NHANES III survey indicated that only 5% of 18-year-old to 24-year-old adults and 2% of 25-year-old to 39-year-old adults have evidence of dental sealants.2

Dental sealants are the most cost-effective caries preventive measure for pits and fissures due to their one-time application process.3 Topical fluoride, on the other hand, may need to be applied four times a year. Although fluoride has proven effective in reducing carious lesions on the smooth surfaces of enamel, it does not sufficiently address caries found on the occlusal pits and fissures of teeth.4 Even though occlusal surfaces make up 12% of the tooth surfaces in the mouth, the pits and fissures are approximately eight times more vulnerable than smooth surfaces.5 The occlusal surfaces of premolars and molars, lingual grooves and pits of maxillary molars and incisors, and the buccal pits of mandibular molars are especially susceptible to caries attack.6

THE SEALANT STORY

Buonocore first described the fundamental principles of sealant placement in 1955.7 Controlled clinical studies were conducted throughout the mid-1960s, and in 1976 the American Dental Association published a statement officially accepting sealant placement as a safe and clinically-effective method of preventing dental caries.8

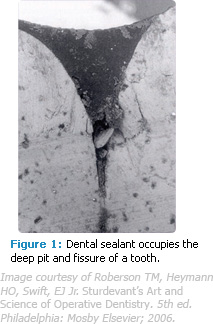

The philosophy behind sealants’ efficacy is simple: a liquid resin flows into the deep crevices and fissures on the occlusal surfaces of teeth, forming a physical barrier between the tooth and any bacterial invasion (Figure 1). In 1969 Keyes described three etiological factors that interact simultaneously to allow caries to occur and progress: a susceptible host, cariogenic microflora, and a suitable substrate (sugars).9 Sealants deprive cariogenic bacteria of their nutritional source, thus arresting the caries process.10

SEALANT USE IN ADULTS

Streptococcus mutans, the dominant member of the plaque flora responsible for decay, uses the tooth’s pits and fissures as a niche for multiplying and producing large amounts of acids capable of destroying tooth structure. When a sealant sets up and becomes hard, it forms a physical barrier between the tooth and any invading bacterial species. This prevents colonization by caries-causing bacteria.

Research shows that the application of sealants in suspect fissures is advisable for adults with high caries risk. Stahl found that the most susceptible teeth involving occlusal caries among adults were molars, especially second molars. Among study participants whose initial molars erupted at approximately 6 years of age, he found a 9.9% incidence of caries in occlusal molars 11 years to 14 years post-eruption. This same group, with second molars erupting at approximately 12 years, exhibited an occlusal caries incidence rate of 14% 5 years to 8 years post-eruption.11

The occlusal surfaces of premolars and molars, lingual grooves and pits of maxillary molars and incisors, and the buccal pits of mandibular molar surfaces are more susceptible to caries because of erosion and/or changes in the intrinsic factors of saliva, which put adults of all ages at risk. Individuals 40 years and older, for example, are often on lifelong medication therapies that cause systemic and oral complications, including xerostomia, which may increase caries susceptibility. Dental sealants can inhibit the advancement of caries in many of these cases and may be the treatment of choice for borderline carious lesions.

Posterior teeth may remain susceptible to caries for many years with secondary recurrent caries being the primary reason for the failure and replacement of restorations among adults. Research has shown, however, that sealants can improve these statistics on the occlusal surfaces of teeth.4 Mertz-Fairhurst demonstrated in numerous trials that the sealing of amalgam restoration margins immediately after placement can improve the longevity of the final restoration.4

CARIES PREVALENCE

Statistics regarding caries reduction are revealing. The NHANES III study reported that 78% of 17-year-olds had tooth decay with an average of seven affected tooth surfaces.2 Beck and Field discovered that among dentulous patients in Iowa older than 65 years, 90% had coronal decay and 39% had untreated carious root lesions.12

The focus in reducing caries should be on prevention strategies. More than 100 million Americans do not live in communities with fluoridated water.13 In the United States, 80% of local health departments do not offer any dental programs,14 and nearly 93% of Americans older than 40 years have not had an oral cancer examination in the past year.15 More than 125 million Americans do not have dental insurance, and 81% of nursing home residents have not had a dental visit within the past year.14

|

|

REDUCING CARIES RISK

Sealants are effective in reducing dental caries among children and adults. Ripa reviewed 41 reports of 24 sealant effectiveness studies and discovered significant caries reduction in populations where sealants had been used. Reductions varied from 82% after 1 year post-sealant application to 34% after 7 years.16 A longevity study by Simonsen revealed a one-time application of sealants was responsible for reducing caries by 52% during a 15-year period.17 In a study on military recruits, the use of dental sealants tripled over a 4-year period (1987-1991), which resulted in a significant decrease in one-surface amalgam restorations.18

Many oral health care providers object to placing sealants because they are afraid of inadvertently placing sealants over incipient carious lesions, with concern the caries will progress undetected and eventually advance to the pulp. This issue is addressed by studies that demonstrate carious lesions will not progress as long as the pit and fissure remains sealed and intact.19 Separate studies also showed that radiographically evident caries did not progress over a 10-year period when sealed.20

Dental sealants can remain completely intact for up to 7 years after one application compared to the lifespan of an amalgam restoration, which ranges from 4 years to 8 years.21 When the National Institutes of Health and the National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research held a conference on dental sealants, the final consensus revealed the “expected” danger from sealing undetectable caries may actually be successful in stopping the caries process.21 In forming a physical barrier between bacteria and the nutrients commonly found in the oral environment, the cariogenic bacteria, including S. mutans, cannot survive and, thus, the sealed carious lesion becomes sterile in nature and cannot progress.22

IMPROVING DENTAL SEALANT RETENTION IN ADULTS

The complete retention rates of dental sealants after 1 year are 85% or better, and after 5 years the number is at least 50%.21 In a military-based study, Simecek found that 87.8% of the dental sealants placed were still retained after 35 months.23 Should a portion of the sealant become lost over time, it can simply be repaired. Romcke et al proved occlusal caries could be reduced by 95% over 10 years if 2% to 4% of the sealants were routinely repaired each year.24

Foreman asserts that the routine adult prophylaxis appointment is the ideal time for the evaluation and repair of sealants,18 although there are differences in opinion as to how a repair should be made. Romcke et al repaired defective sealants in instances where a pit or fissure had been exposed.24 Using these criteria, there was virtually no difference between sealant placement and sealant repair. They estimated one-fourth of the sealants were repaired over a 10-year period.24

|

|

THE DENTAL HYGIENIST’S ROLE

Dental hygienists can repair lost or missing dental sealants in approximately 2 minutes to 5 minutes. Figures 2 through 5 illustrate the placement of a light-cured sealant on a molar tooth.

Dental hygienists can apply sealants in all 50 states but each state has different parameters for application.25 Eight states require that dental hygienists be directly supervised by a dentist while applying sealants. The other 42 states require a variation of general supervision or the option for direct access depending on the setting and the practitioner’s level of education.

In 38 states, dental assistants can apply sealants.26 The dentist is ultimately responsible for the screening process, however, shifting the application and repair of sealants to dental hygienists or dental assistants can boost the efficiency, productivity, and cost-effectiveness of a sealant program.15 Annual dental appointments for adult patients could include a re-evaluation of sealant retention as part of a long-term preventive maintenance program.

Combining the effects of fluoride on smooth surface caries with the routine, aggressive use of sealants against pit and fissure caries has the potential to eradicate caries in children, adolescents, and adults.4 Ongoing innovation in sealant technology and the broadening of the roles of dental team members will help the dental profession achieve this important goal.

REFERENCES

- Leal FR, Simecek JW. A prospective study of sealant application in Navy recruits. Mil Med. 1998;163:107–109.

- Selwitz R. The prevalence of dental sealants in the US population: findings from NHANES III, 1988–1991. J Dent Res. 1996;75(Spec No):652-660.

- Weintraub JA. Pit and fissure sealants in high-caries-risk individuals. J Dent Educ. 2001;65:1084–1090.

- Mertz-Fairhurst EJ. Cariostatic and ultraconservative sealed restorations: six-year results. Quintessence Int. 1992;23:827–838.

- Harris NO, Garcia-Godoy F. Primary Preventive Dentistry. 6th ed. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson Prentice Hall; 2004:285.

- Barr JH, Stephens RG. Incidence of caries at different locations on the teeth. J Dent Res. 1957;36:536–545.

- Buonocore M. A simple method of increasing the retention of acrylic filling materials to enamel surfaces. J Dent Res. 1955;34:849–853.

- Council on Dental Materials and Devices. Pit and fissure sealants. J Am Dent Assoc. 1976;93:134.

- Keyes P. Present and future measures for caries control. J Am Dent Assoc. 1969;79: 1395–1404.

- Mertz-Fairhurst EJ, Curtis JW Jr, Ergle JW, Rueggeberg FA, Adair SM. Ultraconservative and cariostatic sealed restorations: results at year 10. J Am Dent Assoc. 1998;129:55–66.

- Stahl J. Occlusal dental caries incidence and implications for sealant programs in a US college student population. J Public Health Dent. 1993;53:212–218.

- Beck JD, Field HM. Prevalence of root caries and coronal caries in a non–instiutionalized old population. J Am Dent Assoc. 1985;111: 964–967.

- Hinman AR, Reeves TR. The US experience with fluoridation. Community Dent Health. 1996;13(Suppl 2):5–9.

- US Department of Health and Human Services. Healthy People 2010: Oral Health Objectives. Available at: www.cdc.gov/oralhealth/topics/healthy_people.htm. Accessed May 27, 2011.

- Horowitz AM. Patterns of sceening oral cancer among US adults. J Public Health Dent. 1996;56:331–335.

- Ripa L. The current status of pit and fissure sealants: a review. J Can Dent Assoc. 1985;5:367–380.

- Simonsen R. Retention and effectiveness of dental sealants after 15 years. J Am Dent Assoc. 1991;122:34–42.

- Foreman F. Sealant prevalence and indication in a young military population. J Am Dent Assoc. 1994;125:182–184, 186.

- Mertz-Fairhurst EJ. Cariostatic and ultraconservative sealed restorations: nine-year results among children and adults. ASDC J Dent Child. 1995;62:97–107.

- Briley JB, Mertz-Fairhurst EJ. Radiographic analysis of previously sealed carious teeth. J Dent Res. 1994;73:416.

- National Institutes of Health Consensus Development Conference statement on dental sealants in prevention of tooth decay. J Am Dent Assoc. 1984;108:233–236.

- Mertz-Fairhurst EJ, Schuster GS, Williams JE, Fairhurst CW. Clinical progress of sealed and unsealed caries. Part I. Depth changes and bacterial counts. J Prosthet Dent. 1979;42:521–526.

- Simecek JW, Ahlf RL, Ragain JC Jr. Dental sealant longevity in a cohort of young US naval personnel. J Am Dent Assoc. 2005;136:171–178.

- Romcke RG, Lewis DW, Maze BD, Vickerson RA. Retention and effectiveness of fissure sealants over 10 years. J Can Dent Assoc. 1990;56:235–237.

- American Dental Hygienists’ Association. Sealant Application—Settings and Supervision Levels by State. Available at: www.adha.org/governmental_affairs/downloads/sealant.pdf. Accessed May 27, 2011.

- Dental Assisting National Board Inc. Certified Preventive Dental Assistant Certification. Available at: www.danb.org. Accessed May 27, 2011.

From Dimensions of Dental Hygiene. June 2011; 9(6): 66-69.