ELMIK / STOCK / THINKSTOCK

ELMIK / STOCK / THINKSTOCK

Managing Deep Caries

Vital pulp therapy can be a useful option for treating severe caries in primary molars.

This course was published in the May 2016 issue and expires May 31, 2019. The authors have no commercial conflicts of interest to disclose. This 2 credit hour self-study activity is electronically mediated.

EDUCATIONAL OBJECTIVES

After reading this course, the participant should be able to:

- Discuss the factors involved in pulpal diagnosis in primary teeth.

- In primary molars, compare and contrast pulpotomy with indirect pulp treatment.

- Identify the essential components of an ideal restoration for primary molars for which vital pulp therapy has been performed.

Successful management of deep caries lesions begins with an accurate pulpal diagnosis. Such a diagnosis can be achieved after the patient’s history of symptoms and clinical and radiographic findings have been reviewed. Assessing the pulpal status of primary teeth can be the most difficult part of vital pulp therapy. In part, this is because the diagnostic tools used in adult endodontic diagnosis are not effective in primary teeth. For example, determining an accurate pulpal diagnosis based on clinical signs and symptoms is nearly impossible without a detailed medical and dental history, and children are not reliable providers of such information. Both the pediatric patient and his or her parent/caretaker need to be questioned about the child’s symptoms. Although it is possible for a tooth with extensive disease to present without any history of pain, pain is usually associated with pulpal inflammation.1 While pain generated by a stimulus is typically reversible, spontaneous pain usually indicates extensive degenerative changes that have extended into the pulp. As such, teeth with a history of spontaneous pain are not candidates for vital pulp therapy.1,2

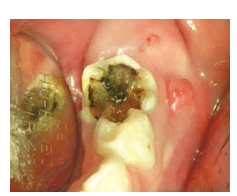

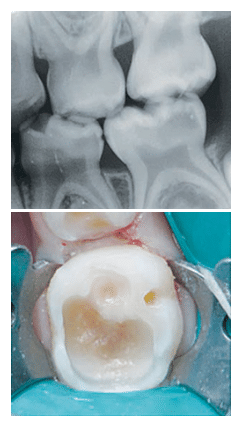

Besides a history of pain, soft tissue changes, pathological mobility, and percussion sensitivity should also be evaluated during a clinical examination. A sinus tract or radiographic indications of a periradicular abscess are signs of a necrotic pulp, in which case, vital pulp therapy is inappropriate (Figure 1). The presence of tooth mobility beyond the level of what’s seen during normal exfoliation is also a contraindication for vital pulp therapy. Percussion sensitivity can be a sign of a necrotic pulp; however, the reliability of a child’s response to this test is questionable. Moreover, the possibility of causing pain during percussion testing may frighten a pediatric patient.2 Thus, pulp vitality testing is not typically used on primary teeth.

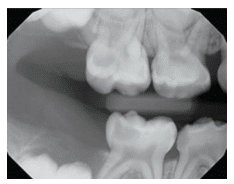

High-quality radiographs are needed for accurate diagnosis. In primary molars, pathological changes in the furcation areas may best be detected by bitewing radiographs (Figure 2). The loss of lamina dura and decreased radiopacity of the bone in the furcation area are signs of necrotic or dying pulps (Figure 3).2 External or internal root resorption are also signs of advanced pulpal pathoses.1

Bitewings provide the most accurate assessment of the depth of the caries lesion and its proximity to the pulp. Unfortunately, taking bitewings on young children to capture furcation areas can be difficult. When challenging, selected periapical radiographs should be captured on teeth with deep caries for diagnostic purposes. The superimposition of partially developing permanent teeth may hinder visibility and make accurate observation of subtle changes to the primary teeth difficult.1,2

The placement of a glass ionomer interim therapeutic restoration (ITR) prior to vital pulp therapy may support the pulpal diagnosis.3–5 ITRs are placed at the initial examination in large cavitated lesions with questionable pulpal states without using local anesthesia or rubber dams. Before the restoration is applied, superficial caries material should be removed with hand instruments or large, slow-speed round burs.3–5

The tooth should be subsequently reevaluated in 1 month to 3 months. At re-evaluation, if the tooth remains clinically and radiographically normal, the pulp is vital or reversibly inflamed and vital pulp therapy can be performed. If clinical or radiographic signs or symptoms of advanced pulpal inflammation are present during the observation period, the pulpal damage is irreversible and extraction or pulpectomy therapy is indicated.4,5 This approach may be particularly helpful in determining the pulpal status of teeth with deep interproximal caries.5

After the observation period is over, if the pulp appears normal or reversible pulpitis is present, a pulpotomy or IPT should be considered. Studies have shown that these therapies have the same indications and similar outcomes.4,6–9

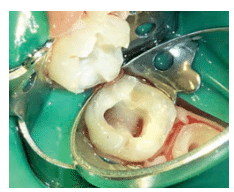

PULPOTOMY

Traditionally, when caries removal in primary teeth results in a carious/mechanical pulp exposure, a pulpotomy is performed.9 During this procedure, the coronal pulp is amputated and the remaining radicular pulp tissue is assessed and treated with a pulp medicament. Afterward, the coronal pulp chamber is filled with a suitable base, and the tooth is restored using a well-sealed restoration.9 All decayed dentin should be removed before entering the pulp chamber to minimize the risk of bacterial contamination. A bleeding pulp inside the pulp chamber indicates a vital pulp. If the pulp chamber is empty or purulent, the pulpotomy should be terminated and a pulpectomy or extraction must be performed.2 Removing all residual hemorrhaging coronal pulp tissue tags hidden underneath the pulp horn is important in controlling bleeding and accurately accessing the pulpal status. Once the coronal pulp is removed using a large, slow-speed round bur or a sharp spoon, a damp cotton pellet with gentle pressure is used to control the hemorrhage from the pulp stumps. If hemostasis can be achieved within several minutes, the radicular tissue is thought to be vital (Figure 4) and the tooth is a good candidate for the pulpotomy. If there is excessive hemorrhage that cannot be controlled, the tooth is not a candidate for vital pulp therapy, and nonvital pulp therapy or extraction must be performed. When the hemorrhaging is controlled, a pulpotomy medicament—such as formocresol, ferric sulfate, or mineral trioxide aggregate (MTA)—should be applied.

Formocresol is the most commonly used pulpotomy agent.10,11 However, safety concerns have arisen because it contains formaldehyde,11 though no correlation between formocresol pulpotomies and cancer has ever been demonstrated.12 The amount of formocresol used in a pulpotomy is minimal. When used prudently, formocresol is a safe, economical, and effective pulp medicament.12 However, studies have shown that the clinical success of formocresol pulpotomy decreases with time.3,4 Ferric sulfate offers a nonformaldehyde option for clinicians concerned about the safety of formocresol and this agent offers similar success rates to formocresol.13 MTA performs as well as or better than formocresol and ferric sulfate and it offers improved biocompatibility.14 While it may become the preferred pulpotomy agent in the future, MTA’s high cost and risk of tooth discoloration have limited its use thus far.15 In recent years, many new MTA-like products with similar properties have been introduced, providing clinicians with more affordable choices. However, long-term clinical studies on thes effectiveness of these products are needed.

INDIRECT PULP TREATMENT

IPT involves covering a small amount of caries that is left in place to avoid pulp exposure with a biocompatible material, such as calcium hydroxide or glass ionomer, then restoring the tooth with a restoration that seals the tooth from microleakage.2,9 IPT works by removing the superficial layer of carious dentin while leaving a small layer of affected dentin that contains a minimal amount of bacteria. The caries lesion is then sealed. When this approach goes as planned, the caries is arrested, the affected dentin remineralizes, and tertiary dentin forms inside the pulp chamber.16–18 Re-entry is not required.18 When performing IPT, all lateral walls must be excavated to sound dentin, and only the smallest amount of caries located over the pulp is left behind (Figure 5). A sound understanding of the internal anatomy of primary teeth helps practitioners avoid overly aggressive caries removal and thus decrease the risk of pulp exposure.19,20 A slow-speed handpiece with a large, round bur is recommended to provide controlled tissue excavation.2

IPT has higher success rates than pulpotomy in long-term studies.9 The technique offers many advantages including the prevention of direct pulp injury, maintenance of pulp integrity, avoiding pulpal tissue exposure to potentially toxic chemicals, shorter treatment time, and no need to reenter. However, pulpotomy remains the more commonly used technique. Accurate pulpal diagnosis is critical for the success of IPT and achieving this in children can be challenging. Other barriers include the historical success of pulpotomy, clinicians’ confidence in its outcomes, and inadequate reimbursement for IPT.21

Modern caries management in primary teeth has evolved from surgical approaches with complete caries removal to a less invasive approach with partial or no caries removal underneath restorations.20,22 The Hall technique is a less invasive approach and studies demonstrate its success.23,24 In this technique, a stainless steel crown (SSC) is cemented over carious primary molars with a glass-ionomer cement. This is done without caries removal, tooth preparation, or local anesthesia.24 In a randomized control trial with 5-year follow-up, sealing in caries with the Hall technique statistically and clinically outperformed conventional intracoronal restorations.22,25 The Hall crown, however, is not suitable for every child or every molar with a caries lesion.26 First, the Hall crown should only be fitted on a tooth that has a low or no risk of irreversible pulpal pathology. Second, Hall crowns require careful follow-up after fitting, and prompt management is indicated if pulpal pathology arises. In addition, very young or anxious children may not be able to cope with the fitting of the crown.

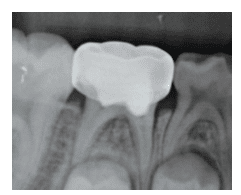

FINAL RESTORATION

Besides accurate preoperative diagnosis, a final restoration that provides a complete biological seal is critical for the success of vital pulp therapy.2,9 Traditionally, SSCs have been the restorations of choice for primary molars. However, parents often prefer tooth-colored restorations.27 Veneered SSCs have been introduced as an esthetic alternative to traditional SSCs, but chipped facing is a possibility over the long term.28,29 In addition, significantly more tooth structure needs to be removed to fit these crowns; thus, the risk of accidental pulp exposure increases during tooth preparation.28

Another esthetic restorative option for primary molars is a resin-based composite. Studies on the use of resin-based composite restorations in primary molars treated with pulpotomies and IPT have shown promising results, particularly on teeth with occlusal restorations.7,8 The most common reason for failure is coronal microleakage. The risk of coronal microleakage increases with the number of surfaces involved.29,30 New esthetic, full-coverage options, such as zirconia crowns, are also available. They offer excellent esthetic outcomes; however, their effects on pulp treatment, surrounding tissue, and opposing natural teeth need long-term observation.

FOLLOW-UP CARE

Clinical and radiographic examinations should be performed every 6 months on teeth treated with vital pulp therapy.9 Treatment is considered clinically successful when there are no clinical signs or symptoms of advanced pulp degeneration. Bitewings capturing the furcation area or periapical radiographs can be compared with preoperative radiographs to evaluate changes over time. Ideally, no change should be observed between preoperative and follow-up radiographs of successfully treated teeth. However, changes in root canals may be observed. Internal resorption and pulp canal obliteration are two commonly seen changes.2 Minor and self-limiting internal resorption can be monitored with no intervention required. However, internal resorption can also be progressive and destructive, even perforating the canals and involving surrounding bone. If this is the case, vital pulp therapy has failed and intervention, such as extraction, is indicated.31 Pulp canal obliteration involves the natural narrowing of canals over time (Figure 6). It is a sign of pulp healing and is considered a treatment success.

CONCLUSION

Primary molars with deep caries can be managed by vital pulp therapy. Both pulpotomy and IPT are suitable treatments for pulp that is healthy or with reversible inflammation. Success of vital pulp therapy depends on accurate pulp diagnoses, careful operative practices, well-sealed restorations, and appropriate follow-up care.

References

- Camp JH. Diagnosis dilemmas in vital pulp therapy:treatment for the toothache is changing, especially in young, immature teeth. J Endod. 2008;34(Suppl 7): S6–S12.

- Seale NS, Coll JA. Vital pulp therapy for the primary dentition. Gen Dent. 2010;58:192–194.

- Vij R, Coll JA, Shelton P, Farooq NS. Caries control and other variables associated with success of primarymolar vital pulp therapy. Pediatr Dent.2004;26:214–220.

- Coll JA. Indirect pulp capping and primary teeth: is the primary tooth pulpotomy out of date? J Endod. 2008;34(Suppl 7):S34–S39.

- Coll J, Campbell A, NI C. Effects of glass ionomer temporary restorations on pulpal diagnosis and treatment outcomes in primary molars. Pediatr Dent.2013;45:416–421.

- Farooq NS, Coll JA, Kuwabara A, Shelton P. Success rates of formocresol pulpotomy and indirect pulp therapy in the treatment of deep dentinal caries in primary teeth. Pediatr Dent. 2000;22:278–286.

- Falster CA, Araujo FB, Straffon LH, Nör JE. Indirect pulp treatment: in vivo outcomes of an adhesive resin system vs calcium hydroxide for protection of the dentin-pulp complex. Pediatr Dent. 2002;24:241–248.

- Casagrande L, Bento LW, Dalpian DM, García-Godoy F, De Araujo FB. Indirect pulp treatment in primary teeth: 4-year results. Am J Dent. 2010;23:34–38.

- American Academy on Pediatric Dentistry ClinicalAffairs Committee-Pulp Therapy subcommittee;American Academy on Pediatric Dentistry Council on Clinical Affairs. Clinical guidelines on pulp therapy for primary and young permanent teeth. Pediatr Dent. 2015;37(Spec Issue 6):244–252.

- Dunston B, Coll JA. A survey of primary tooth pulp therapy as taught in US dental schools and practiced bydiplomates of the American Board of PediatricDentistry. Pediatr Dent. 2008;30:42–48.

- Walker LA, Sanders BJ, Jones JE, et al. Current trends in pulp therapy: a survey analyzing pulpotomy techniques taught in pediatric dental residency programs. J Dent Child (Chic). 2013;80:31–35.

- Milnes AR. Is formocresol obsolete? a fresh look at the evidence concerning safety issues. J Endod. 2008;34(Suppl 7):40–46.

- Peng L, Ye L, Guo X, et al. Evaluation of formocresol versus ferric sulphate primary molar pulpotomy: asystematic review and meta-analysis. Int Endod J. 2007;40:751–757.

- Peng L, Ye L, Tan H, Zhou X. Evaluation of the formocresol versus mineral trioxide aggregate primary molar pulpotomy: a meta-analysis. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2006;102:e40–44.

- Agamy HA, Bakry NS, Mounir MMF, Avery DR.Comparison of mineral trioxide aggregate and formocresol as pulp-capping agents in pulpotomized primary teeth. Pediatr Dent. 2004;26:302–309.

- Ribeiro CCC, de Oliveira Lula EC, da Costa RCN,Nunes AMM. Rationale for the partial removal of carious tissue in primary teeth. Pediatr Dent. 2012;34:39–41.

- Ferreira JMS, Pinheiro SL, Sampaio FC, de MenezesVA. Caries removal in primary teeth—a systematicreview. Quintessence Int. 2012;43:e9–e15.

- Wambier DS, dos Santos FA, Guedes-Pinto AC,Jaeger RG, Simionato MRL. Ultrastructural and microbiological analysis of the dentin layers affected by caries lesions in primary molars treated by minimal intervention. Pediatr Dent. 2007;29:228–234.

- Orhan AI, Oz FT, Orhan K. Pulp exposure occurrence and outcomes after 1- or 2-visit indirect pulp therapy vs complete caries removal in primary and permanent molars. Pediatr Dent. 2010;32:347–355.

- Ricketts D, Lamont T, Innes NPT, Kidd E, Clarkson JE.Operative caries management in adults and children.Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;3:CD003808.

- Seale NS, Glickman GN. Contemporary perspectiveson vital pulp therapy: views from the endodontists andpediatric dentists. J Endod. 2008;34:261–267.

- Innes NP, Evans DJP, Stirrups DR. Sealing Caries inPrimary Molars: Randomized Control Trial, 5-yearResults. J Dent Res. 2011;90:1405–1410.

- Innes NP, Stirrups DR, Evans DJP, Hall N, Leggate M.A novel technique using preformed metal crowns for managing carious primary molars in general practice — a retrospective analysis. Br Dent J. 2006;200:451–454.

- Innes NP, Evans DJ, Stirrups DR. The Hall Technique;a randomized controlled clinical trial of a nove lmethod of managing carious primary molars in general dental practice: acceptability of the technique and outcomes at 23 months. BMC Oral Health.2007;7:18.

- Innes NP, Stewart M, Souster GED. The HallTechnique; retrospective case-note follow-up of 5-yearRCT. Br Dent J. 2015;219:395–400.

- Innes NP, Evans DJP. Modern approaches to caries management of the primary dentition. Br Dent J.2013;214:559–566.

- Zimmerman J, Feigal R, Till M, Hodges J. Parental attitudes on restorative materials as factors influencing current use in pediatric dentistry. Pediatr Dent.2009;31:63–70.

- Ram D, Fuks AB, Eidelman E. Long-term clinicalperformance of esthetic primary molar crowns. PediatrDent. 2003;25:582–584.

- Guelmann M, Shapira J, Silva DR, Fuks a B. Esthetic restorative options for pulpotomized primary molars: are view of literature. J Clin Pediatr Dent. 2011;36:123–126.

- Guelmann M, McIlwain MF, Primosch RE.Radiographic assessment of primary molar pulpotomies restored with resin-based materials .Pediatr Dent. 2005;27:24–27.

- Huth KC, Paschos E, Hajek-Al-Khatar N, et al.Effectiveness of 4 pulpotomy techniques—randomized controlled trial. J Dent Res. 2005;84:1144–1148.

From Dimensions of Dental Hygiene. May 2016;14(05):62–65.