Improve Patient Communication

From using professional interpretation services to addressing low health literacy, ensuring effective communication between patients and providers is Integral to positive outcomes.

This course was published in the March 2018 issue and expires March 2021. The authors have no commercial conflicts of interest to disclose. This 2 credit hour self-study activity is electronically mediated.

EDUCATIONAL OBJECTIVES

After reading this course, the participant should be able to:

- Identify types of language barriers and discuss their impact on patient outcomes.

- Assess whether a language barrier exists between patient and provider.

- Discuss best practices when working with an interpreter.

- Identify strategies to increase health literacy.

For patients who only understand a portion of the information provided by health care professionals, it is nearly impossible to take medications properly, access appropriate services, and obtain accurate diagnoses. Studies show that language miscommunications are associated with misdiagnosess, drug errors, patient dissatisfaction, and overall poor health outcomes.1–5 Language barriers and poor health literacy can contribute to communication breakdowns between clinicians and patients. Oral health professionals need to be prepared to overcome such issues in order to provide the best care possible and achieve positive outcomes.

LANGUAGE BARRIERS

While many language barriers can cause miscommunication, this article will focus on two types. The first is when patients and providers speak different languages. The second is when patients and providers speak the same language, but a patient is unable to decipher the information provided. Finding solutions to language barriers is important in eliminating health-care disparities and improving patient-provider communication, outcomes, and patient satisfaction.6,7

The Institute of Medicine Committee on Understanding and Eliminating Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Health Care published a report on enhancing communication between patients and providers to combat disparities.8 It suggests using language interpretation services when caring for communities in need. Language interpretation services are vital because approximately 25.9 million or 8.6% of people in the United States speak or understand English with limited proficiency.9 Limited English proficiency (LEP) refers to individuals age 5 and older who report speaking English language less than “very well.”9Oral health professionals are likely to see patients whose first language or the language spoken at home is something other than English.

Many regulations govern interpreters and oral health. In fact, any patient receiving federal financial assistance is covered by Title VI of the Civil Rights Act, which protects individuals from discrimination based on color, race, or national origin.10 Under this law, language is a tacit substitution for national origin.11 Failure to provide language access for patients with LEP is considered discrimination.12 As such, dental patients with LEP covered by Medicaid should have access to interpreter services.

Understanding the information provided by health care providers is a basic human need. The American Dental Hygienists’ Association’s (ADHA) Code of Ethics provides a standard of professional responsibility that includes providing services to patients without discrimination.13 The ADHA Code of Ethics also recommends that dental hygienists provide patients with adequate information to make informed decisions about their oral health. Patients who do not understand their treatment options are unable to make informed decisions. Consenting is more than just a formal written legal process, but rather ensuring patients understand the risks and benefits of both accepting and declining treatment.14

The effective use of an interpreter begins by first identifying the need for such services. Assessing how well a patient can speak and understand English is the first step. The easiest barrier to identify is a complete language barrier. This results when communication is not possible due to the severity of language discordance. Another way to identify a language barrier is when a patient responds in limited phrases. For example, the patient might answer “yes, thank you” to all questions. To ameliorate this situation, it is best to refrain from asking “yes” or “no” questions and opt for open-ended questions, such as, “What brings you in today?”

In addition, patients may be difficult to understand, or may not be able to respond to questions in English. If you suspect a patient has limited English proficiency, let the patient know that interpretation services are available and are sometimes free of charge.15 Patients may also self-report language preference on a health history form. This may be helpful when determining if an interpreter is needed. While self-reported language preference can be a helpful screening tool, few studies support its efficacy in determining the need for interpreter services.15 Regardless, patients should be informed of the availability of language assistance services in their preferred language both verbally and in writing.16

INTERPRETER SERVICES

Once the need for interpreter services has been determined, a trained or certified interpreter should be sought. When given a choice, most patients prefer the use of professional interpreters to the use of friends, family, untrained staff, or minor children.17 The use of nonprofessionals for impromptu interpretation is known as ad-hoc interpretation.18 While it may appear to be more convenient to use a volunteer who is fluent, especially if he or she is easily accessible, ad hoc interpreters may be unfamiliar with dental terminology or have minimal health literacy.19 Professional interpreters will help ensure accuracy of translation and act as a culture broker to close communication gaps. Cultural brokering is needed because the mere translation of language does not take into account certain phrases or terminology. In addition, professional interpreters also help ensure patient privacy, confidentiality, and respect.20 The use of children should be avoided with the exception of emergencies, as they are unable to understand complex medical issues.19,21Family members should also be avoided to circumvent issues of confidentiality, ulterior motives, and to minimize errors.21 The use of bilingual employees should only be used when a professional interpreter is unavailable, and those employees should be encouraged to pursue additional training.19

BEST PRACTICES

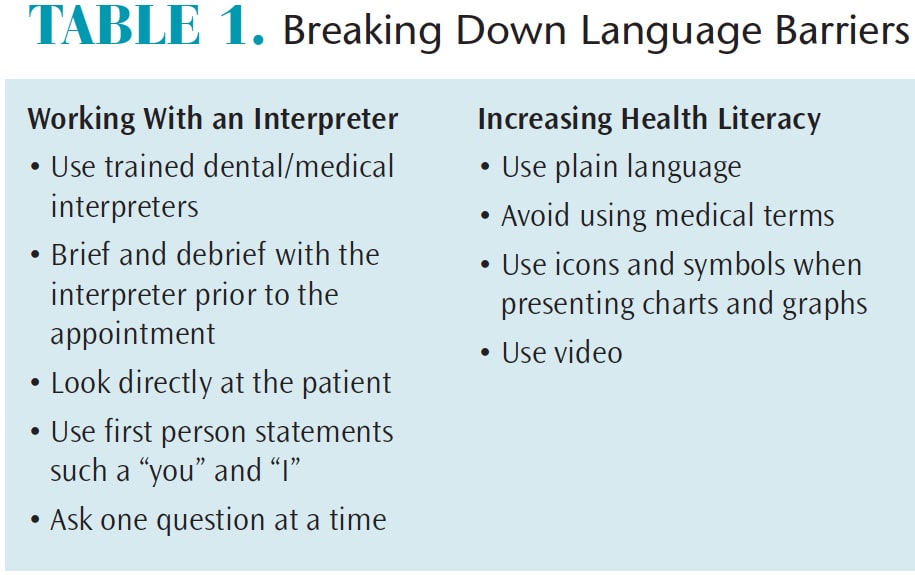

Best practices in the appropriate use of an interpreter are simple, easy to incorporate, and facilitate optimal communication (Table 1). It is best to brief and debrief with the interpreter before and after the consultation, as this provides the opportunity to ensure the interpreter is fluent in the same language/dialect as the patient. Once the patient arrives, the discussion should be directed to the patient, not the interpreter. The oral health professional should look at the patient when speaking. It is best to use first person statements including “I” and “you.”19 Using third person statements, such as “he” or “she,” should be avoided as discussion ought to be addressed to the patient and not the interpreter.19 Make sure to emphasize two to three key points, so as to not overwhelm the patient.19 Ask only one question at a time and allow appropriate time for the interpreter to finish the statement.19

FINANCIAL IMPLICATIONS

FINANCIAL IMPLICATIONS

The benefits of using an interpreter outweigh the cost.22 Interpreters can be hired on a freelance basis or from an interpreter agency with the cost ranging from $1.25 to $3.00 per minute.22 In some states, the cost of interpretation services are covered wholly or partially by Medicaid or Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP).23 In the US, language services are reimbursed in 13 states, but provisions in each state vary greatly in reimbursement rates, processes, and requirements.23 Some states will only reimburse businesses with whom they are contracted, while other states require interpreters to be certified and have received training in order to qualify for reimbursement.23 Interpreters may be paid directly or by the provider prior to submitting a claim for reimbursement.23Segments for interpreter travel time and telephonic services may also exist.23 The National Health Law Program has published “Medicaid and CHIP Reimbursement Models for Language Services,” which provides requirements or eligibility for language services in specific areas.

Not using an interpreter can raise the risk of legal liability. Recorded medical malpractice settlements due to inadequate communication have cost health care providers millions.5 The benefits of using an interpreter when necessary outweigh the financial costs to business owners and health care providers.

HEALTH LITERACY

Health literacy is the degree to which individuals have the capacity to obtain, process, and understand basic health information and services needed to make appropriate health decisions.24 Only 12% of adults are considered proficient in health literacy.25 Those with low socioeconomic status, limited education, and patients who are LEP are at high risk.26 Low health literacy greatly impacts health. For example, an individual with low health literacy is more likely to solicit services for secondary prevention, such as treatment of diseases, rather than primary preventive services.27 One study found that patients with low health literacy were less likely to access flu shots and other immunizations, health screenings, and other preventive services.27 In addition, adults with low health literacy are more likely to have poor physical and mental health.28

A 1995 study of health literacy found that 20% to 31% of patients could not explain an appointment slip; 33% to 60% were unable to determine if they qualified for financial assistance; and 11% to 33% could not understand a standard set of instructions.29 In addition, 23% of respondents brought someone in to help them understand printed material.29 Since this study was conducted, health literacy research has evolved from not only coding and decoding word lists but understanding how a patient interacts and uses health information.6 The World Health Organization defines health literacy as the “ability for a person to engage with health information and services in a meaningful way.”30 Thus, it is not just the ability to read and write but also the ability to use health information to make the best decisions about health care. Health literacy can be used in two ways. The first as indicator of disease risk and the second as an health promotion strategy to combat health disparities.31

IDENTIFYING THOSE WITH LOW HEALTH LITERACY

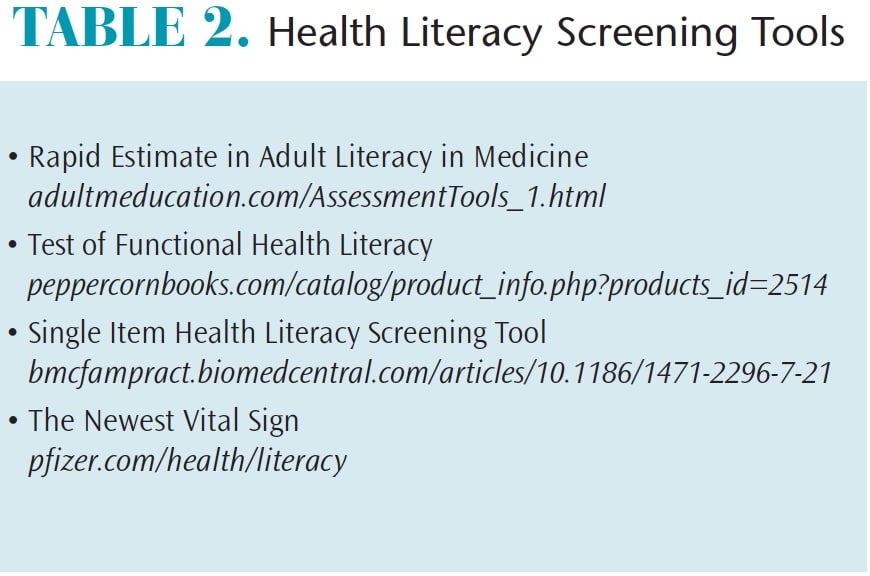

Implementing strategies to increase oral health literacy will help patients be better stewards of their oral health.32 Oral health professionals are often able to identify health literacy levels during patient conversations. There are also questionnaires available (Table 2). These tests are based largely on reading literacy, with an emphasis on vocabulary and reading level.

There are two single item health literacy-screening questions that can be asked to assess health literacy in adults. The questions are simple and may be easily incorporated into a patient intake form. One question is “How often do you need to have someone help you when you read instructions, pamphlets, or other written material from your doctor or pharmacy?”33 The other question is “How confident are you filling out medical forms by yourself?”33 One critique of this tool is that the “filling out of forms by yourself” may be interpreted as the physical ability to complete a form.33

There are two single item health literacy-screening questions that can be asked to assess health literacy in adults. The questions are simple and may be easily incorporated into a patient intake form. One question is “How often do you need to have someone help you when you read instructions, pamphlets, or other written material from your doctor or pharmacy?”33 The other question is “How confident are you filling out medical forms by yourself?”33 One critique of this tool is that the “filling out of forms by yourself” may be interpreted as the physical ability to complete a form.33

BARRIERS TO HEALTH LITERACY

There are many barriers to health literacy.7 Often, patient information includes professional medical jargon or a health professional uses vocabulary that is too complex to understand.7 Health information may be difficult to understand regardless of education level.34Those with minimal education are at highest risk for language barriers, but even well-educated patients may experience difficulty understanding health-specific terminology.

Understanding disease etiology and health information requires patients to grasp complex processes, such as numeracy, immune system functions, probability, etc. To understand bacterial plaque biofilm, a patient would need knowledge of bacterial reproduction, exponential multiplication, quorum sensing, and genetic and biochemical details. To grasp the host response, a patient would need to understand inflammation, including the pathogenesis of periodontal diseases.35 For a patient to truly understand the difference between gingivitis and periodontitis, a solid understanding of anatomical structures, alveolar height, and the anatomy of the supporting tissues is needed. Oral health professionals are an important channel in the exchange of information. They must be cognizant of the level of information patients need to make appropriate health choices.

STRATEGIES TO INCREASE ORAL HEALTH LITERACY

One strategy to help eliminate health disparities is to use plain language, which is language that is easily understood the first time it is read or heard. Plain language should be used in both oral and written materials. Jargon and technical terms should be avoided.31 If technical terms must be used, they should be first defined in simple language. This does not necessarily mean that information must be “dumbed down,” but rather tailored to the audience. One office can have several different educational brochures or patient materials covering the same topic.

Educational materials should be tested before, during, and after they are dispersed. When developing educational material, the information should be organized first by stating a document’s purpose and following with the most important information.26 Many patients find health information online, but there is no evidence to suggest that teaching people to find and evaluate online health information will improve their health.36

Presenting materials in a different manner is another strategy to improve health literacy.31 Using grade school language and vocabulary and employing videos can be helpful. When presenting data, the information can be displayed pictorially with icons and symbols.31 Oral health professionals should continue to stay abreast of strategies to increase oral health literacy as the field continues to emerge and evolve.

SUMMARY

Language barriers are a large contributing factor to health disparities in the US. They exist not only when a provider’s language does not match that of a patient’s, but also when the core messages being communicated are not reaching the patient. This can be alleviated by hiring an interpreter in tandem with using plain language in both spoken and written materials. While providing dental services, oral health professionals will likely encounter patients whose language needs are different from their own. Armed with health literacy as a strategy to eliminate health disparities and the willingness to use interpreters effectively, oral health professionals can overcome language barriers and be a conduit for positive change in patient outcomes.

REFERENCES

- Wilson CC. Patient safety and healthcare quality: The case for language access. Int J Health Policy Manag. 2013;1:251–253.

- Wasserman M, Renfrew MR, Green AR, et al. Identifying and preventing medical errors in patients with limited english proficiency: key findings and tools for the field. J Healthc Qual. 2014;36:5–16.

- Morales LS, Cunningham WE, Brown JA, Liu H, Hays RD. Are Latinos less satisfied with communication by health care providers? J Gen Intern Med. 1999;14:409–417.

- Eneriz-Wiemer M, Sanders LM, Barr DA, Mendoza FS. Parental limited English proficiency and health outcomes for children with special health care needs: a systematic review. Acad Pediatr. 2014;14:128–136.

- Flores G. Language barriers to health care in the United States. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:229–331.

- Chinn D. Critical health literacy: a review and critical analysis. Soc Sci Med. 2011;73:60–67.

- Schyve PM. Language differences as a barrier to quality and safety in health care: the joint commission perspective. J Gen Intern Med. 2007;22(Suppl 2):360–361.

- Institute of Medicine Committee on Understanding and Eliminating Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Health Care; Smedley BD, Stith AY, Nelson AR, eds. Unequal Treatment: Confronting Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Health Care. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2003.

- Language Diversity and English Proficiency in the United States. Available at: migrationpolicy.org/article/language-diversity-and-english-proficiency-united-states. Accessed February 15, 2018.

- Chen J, Vargas-Bustamante A, Mortensen K, Ortega AN. Racial and ethnic disparities in health care access and utilization under the Affordable Care Act. Med Care. 2016;54:140–146.

- Chen AH, Youdelman MK, Brooks J. The legal framework for language access in healthcare settings: title vi and beyond. J Gen Intern Med. 2007;22(Suppl 2):362–367.

- Limited English Proficiency. LEP and Title VI Videos. Available at: lep.gov/video/video.html. Accessed February 15, 2018.

- American Dental Hygienists’ Association. Bylaws & Ethics. Availabel at: adha.org/bylaws-ethics. Accessed February 15, 2018.

- Basu G, Costa VP, Jain P. Clinicians’ obligations to use qualified medical interpreters when caring for patients with limited english proficiency. AMA J Ethics. 2017;19:245.

- Okrainec K, Miller M, Holcroft C, Boivin JF, Greenaway C. Assessing the need for a medical interpreter: are all questions created equal? J Immigr Minor Health. 2014;16:756–760.

- National Standards for Culturally and Linguistically Appropriate Services in Health and Health Care. Available at: thinkculturalhealth.hhs. gov/assets/pdfs/EnhancedNationalCLASStandards.pdf. Accessed February 15, 2018.

- Krupic F, Samuelsson K, Fatahi N, Skoldenberg O, Sayed-Noor AS. Migrant general practitioners’ experiences of using interpreters in health-care: a qualitative explorative study. Med Arch. 2017;71:42–47.

- Carr SE, Roberts RP, Dufour A, Steyn D. The Critical Link: Interpreters in the Community. Amsterdam: John Benjamins Publishing; 1997:332.

- Juckett G, Unger K. Appropriate use of medical interpreters. Am Fam Physician. 2014;90:476–480.

- Rosenberg E, Seller R, Leanza Y. Through interpreters’ eyes: comparing roles of professional and family interpreters. Patient Educ Couns. 2008;70:87–93.

- Flores G, Abreu M, Barone CP, Bachur R, Lin H. Errors of medical interpretation and their potential clinical consequences: A comparison of professional versus ad hoc versus no interpreters. Ann Emerg Med. 2012;60:545–553.

- Jacobs EA, Shepard DS, Suaya JA, Stone EL. Overcoming language barriers in health care: costs and benefits of interpreter services. Am J Public Health. 2004;94:866–869.

- Youdelman MK. Medicaid and CHIP reimbursement models for language services. Available at: healthlaw.org. Accessed February 15, 2018.

- Quick Guide to Health Literacy. Fact Sheet. Available at: health.gov/communication/literacy/quickguide/factsbasic.htm. Accessed February 15, 2018.

- America’s Health Literacy: Why We Need Accessible Health Information. Available at: health.gov/communication/literacy/issuebrief. Accessed February 15, 2018.

- Wizemann TM, Institute of Medicine Health Literacy Implications for Health Care Reform: Workshop Summary. Available at: http://libproxy. unm.edu/login?url=http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=nlebk&AN=381804&site=ehost-live&scope=site. Accessed February 15, 2018.

- Scott TL, Gazmararian JA, Williams MV, Baker DW. Health literacy and preventive health care use among Medicare enrollees in a managed care organization. Med Care. 2002;40:395–404.

- Wolf MS, Gazmararian JA, Baker DW. Health literacy and functional health status among older adults. Arch Intern Med. 2005;165:1946–1952.

- Williams MV, Parker RM, Baker DW, et al. Inadequate functional health literacy among patients at two public hospitals. JAMA. 1995;274:1677–1682.

- World Health Organization. Health Literacy Toolkit for Low- and Middle-Income Countries. Available at: searo.who.int/healthpromotion/documents/hl_tookit/en/. Accessed February 15, 2018.

- Campbell ZC, Stevenson JK, McCaffery KJ, et al. Interventions for improving health literacy in people with chronic kidney disease. Available at: http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/14651858.CD012026/abstract. Accessed February 15, 2018.

- American Dental Association. What is Health Literacy in Dentistry? Available at: ada.org/en/public-programs/health-literacy-in-dentistry/what-is-health-literacy-in-dentistry. Accessed February 15, 2018.

- Quinzanos I, Hirsh JM, Bright C, Caplan L. Cross-sectional correlation of single-item health literacy screening questions with established measures of health literacy in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Rheumatol Int. 2015;35:1497–1502.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Available at: cdc.gov/healthliteracy/learn/ Understanding.html. Accessed February 15, 2018.

- American Academy of Periodontology. Periodontal Disease Fact Sheet. Available at: perio.org/newsroom/periodontal-disease-fact-sheet. Accessed February 15, 2018.

- Car J, Lang B, Colledge A, Ung C, Majeed A. Interventions for enhancing consumers’ online health literacy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011;6:CD007092

From Dimensions of Dental Hygiene. March 2018;16(3):42-44,47.