Gummy Smile Correction

Many treatment options are available for patients who want to improve the esthetics of their smile while reducing excess gingival display.

This course was published in the March 2013 issue and expires March 2016. The authors have no commercial conflicts of interest to disclose. This 2 credit hour self-study activity is electronically mediated.

EDUCATIONAL OBJECTIVES

After reading this course, the participant should be able to:

- Discuss the different causes of a “gummy smile.”

- Identify the classifications of altered passive eruption and vertical maxillary excess and the recommended treatments for each category.

- List the different treatment options for excess gingival display.

A beautiful smile is highly valued in today’s society. A broad exposure of the gingiva or excess gingival display during a smile is often considered displeasing and distracting.1 In more severe cases, overexposure of the gingiva is also seen in repose of the lips. A “gummy smile” is a frequent complaint from patients seeking improvement in their esthetic appearance.

A smile is considered unattractive when more than 4 mm of gums are exposed.2 A gummy smile could be localized in nature and involve only few teeth (Figure 1A and Figure 1B), or more commonly generalized, affecting the entire cosmetic zone (maxillary anterior teeth), as seen in Figure 2. Gummy smiles may be caused by excess gingival display or due to severe attrition of the clinical crowns.

Women tend to experience a gummy smile more often than men. Tjan et al report that approximately 7% of men and 14% of women have excess gingival display in full smile.3 Similarly, Vig and Brundo4 note that maxillary anterior tooth display was found almost twice as often in women than men. A variety of factors are involved in excess gingival display. As such, reaching a differential diagnosis is critical before treatment options can be recommended to patients. Excess gingival display may be the result of a skeletal deformity caused by an overgrowth of the maxilla in the vertical dimension (vertical maxillary excess), or because of a compensatory extrusion of the maxillary incisors and alveolar bone (dentoalveolar extrusion). This excessive display may also be due to a short upper lip or hyperactivity of the orbicularis oris muscle. In addition, the appearance of “too much gums” may result from failure to complete the passive eruption phase of the teeth (altered passive eruption), varying degrees of gingival overgrowth, or too-short clinical or anatomic crowns. In the majority of cases, two or more etiologies may be responsible for the excess gingival display and should be addressed in the patient’s treatment.

GINGIVAL OVERGROWTH

Gingival overgrowth is a common cause of the unpleasing gummy smile. In these cases, the enlarged gingiva covers the clinical crowns of the teeth in various degrees, creating an unesthetic appearance of excess gingiva. The most common cause of gingival enlargement is inflammation due to the presence of bacterial plaque, but it may also be related to medications that induce gingival enlargement, such as anticonvulsants, immunosuppressants, and calcium channel blockers. Plaque-induced gingival enlargement responds well to a reduction of the bacterial load through meticulous oral hygiene and periodontal scaling and root planing. In cases of drug-induced overgrowth, a medical consultation with the patient’s physician is essential. A substitution of the causative agent with another drug could improve treatment outcomes considerably. In more severe cases, surgical removal of the excess gingival tissue is necessary to restore function and esthetics, as well as to create an environment favorable to maintaining oral hygiene.

Although not as common, gingival overgrowth can be caused by a systemic condition such as diabetes, leukemia, or sarcoidosis. In very rare cases, the cause for the enlargement is genetic, like in hereditary gingival fibromatosis disorder5 (Figure 3). Treatment options include nonsurgical therapy, which requires reduction of the bacterial load via oral hygiene, scaling and root planing, gingival curettage, and antimicrobial mouthrinses or antibiotics. In more severe cases, surgical excision of the excess gingival tissue via gingivectomy and gingivoplasty may be required.

ALTERED PASSIVE ERUPTION

Altered passive eruption (APE) is seen when the free gingival margin is located on the enamel of the apical third of the clinical crown, rather than on the cementoenamel junction (CEJ) or close to it6 (Figure 4). This clinical condition is attributed to a failure in concluding the physiological passive eruption phase. During this phase, the gingiva migrates apically, with a gradual exposure of the crown of the tooth and final stable localization of the dentogingival junction at the tooth’s cervical level. Although APE is quite common,7 its pathogenesis is not fully understood. A number of factors (developmental or genetic) have been implicated, such as the presence of thick, fibrotic gingiva. This type of gingiva tends to migrate apically more slowly during the passive phase than thin gingival tissue, as in cases of hereditary gingival fibromatosis.5

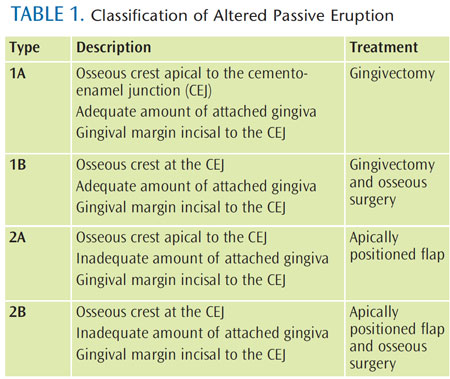

APE can distort the appearance of the teeth by making them appear squarish and short, thus amplifying the displeasing smile (Figure 4). A common observation in these cases is the presence of a thick and irregular buccal bony plate, which tends to increase muscle tension and displace the upper lip to a more apical position during the smile, thus increasing the gingival display. Coslet et al8 classified APE morphologically into two types according to the location of the mucogingival junction with respect to the alveolar bone crest. They also identified two subtypes in reference to the position of the bone crest with respect to the CEJ (Table 1). This classification serves as a general guideline for treating patients with APE.

A surgical intervention aimed at full exposure of the anatomic crown leads to a dramatic and immediate improvement in esthetics. A variety of surgical procedures1 are available for this purpose, such as laser, gingivectomy, flap surgery with or without ostectomy (bone removal), or apically positioned flaps. Selection of the appropriate technique is dictated by the relationship of the gingival margin to the underlying osseous crest, the relationship of osseous crest to the CEJ, and the quantity of attached keratinized gingiva (Figure 1C). In cases of buccal exostoses, a modified technique that requires extensive osteoplasty (recontouring) of the buccal aspect of the alveolar bone, leading to a reduction in the upper lip tension, lengthening of the lip, and increase of the clinical crowns, may provide an overall reduction of the gingival display.9

SHORT CLINICAL CROWNS

The average length of a maxillary central incisor is approximately 10 mm to 11 mm and it varies between men and women. Short maxillary incisors (<9 mm) are usually due to coronal destruction related to an extraoral trauma, caries, or incisal wear. Tooth attrition is most often seen in patients with parafunctional habits, such as bruxism and clenching, which lead to a “pseudo” gummy smile. These cases can be restored esthetically with veneers or crowns, and the parafunctional habits should be controlled with an occlusal guard or other biofeedback therapies.

HYPERACTIVE LIP

In an ideal smile, when the maxillary lip is in a repose position, approximately 3 mm to 4 mm of the maxillary central incisors should be displayed in women and approximately 2 mm less in men.4 Due to the aging process, the upper lip tends to increase in length due to elasticity loss, resulting in decreased visibility of the maxillary incisors and increased exposure of the mandibular antagonists.

In a full smile position, the upper lip should ascend to the gingiva-tooth interface. In a patient with a hyperactive lip, the lip ascends farther apically, approximately one-and-a-half to two times more than the normal distance, exposing excess gingiva and creating an esthetic problem. This condition is caused by hyperfunction of the lip elevator muscles,10 resulting in extensive gingival display. Recently, injection of botulinum toxin type A has been suggested for managing this problem with good esthetic results. However, the benefits are short-lived and must be repeated approximately every 6 months.11 For more lasting results, surgical reposition12 of the maxillary lip is recommended.13 During the surgery, the upper lip is repositioned and sutured in a more coronal position, resulting in shortening of the vestibule. This procedure restricts the muscle pull of the lip elevator muscles, thus reducing the amount of gingival display when smiling.

SHORT LIP

In a repose position, the average length of the maxillary lip in young adult men is 22 mm to 24 mm while in young women, it ranges from 20 mm to 22 mm, when measured from the subnasale to the lower border of the lip.14 If excess gingival display is due to a short lip, restoring esthetics can be challenging. Plastic surgical procedures are necessary similar to the treatment for patients with hyperactive lip.

VERTICAL MAXILLARY EXCESS

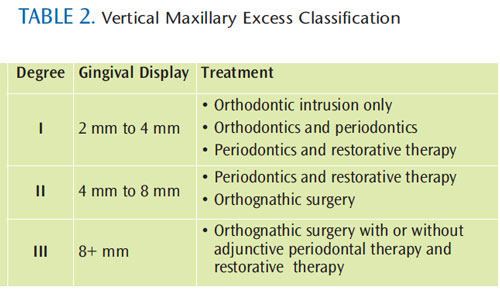

Vertical maxillary excess (VME) is a skeletal anomaly of the face due to overgrowth of the maxillary bone, which causes an enlarged vertical dimension of the mid-face and the appearance of a short lip.15 The length of the upper lip is usually normal, although it may appear short due to the elongated maxillary bone. Garber and Salama16 proposed a classification of VME according to the degree of gingival exposure and corresponding treatment options (Table 2). Treatment of this condition may include a combination of orthodontic and periodontic treatment, as well as orthognathic surgery, to restore normal inter-jaw relationships and to reduce gingival display.17 In more severe cases, orthognathic surgery is usually required to correct the vertical overdevelopment of the maxilla, however, due to the morbidity caused by this type of surgery, many patients choose not to undergo the procedure. In cases like this, periodontal surgery may still help improve esthetic results and provides a reasonable compromise for patients.18

DENTOALVEOLAR EXTRUSION

Dentoalveolar extrusion occurs due to overeruption of the maxillary incisors, leading to a more coronal position of the gingival margins and excess gingival display. In extreme cases of overeruption, the lower lip may cover the incisal edges of the maxillary incisors. This condition is usually seen in Class II malocclusion and in patients missing mandibular incisors.17 Management of this condition may require intrusion of the maxillary incisors into their original positions or, in some cases, orthognathic surgery (Figure 5).

THE ROLE OF THE DENTAL HYGIENIST

Dental hygienists often develop personal relationships with their patients, who they may see several times per year. Due to this rapport- and trust-building, patients tend to feel more comfortable discussing their cosmetic concerns with dental hygienists and often ask for their opinion and recommendations. Dental hygienists are well poised to discuss patients’ concerns and should be familiar with the different factors responsible for a gummy smile. They will then be able to provide information about the different options available to manage this condition, which can “set the stage” for the dentist. If available, dental hygienists can show pre- and post-operative photos of treated patients (who have given consent). After the consultation with the dentist, patients usually receive a proposed treatment plan with different options. Patients may consult with their dental hygienists prior to agreeing on a treatment plan.

CONCLUSION

Excess gingival display is an esthetic concern to patients and a common complaint in the dental operatory. It is essential to understand and correctly diagnose the cause(s) of this condition, as well as provide a complete review of the treatment options available. A thorough clinical examination is critical to achieving a correct diagnosis and esthetic and predictable patient outcomes.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

CREDIT : FIGURE 1A THROUGH FIGURE 1C COURTESY OF MICKEY BERNSTEIN, DDS

CREDIT : FIGURE 3 ©2012 JOURNAL OF THE TENNESSEE DENTAL ASSOCIATION.

CREDIT : ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. REPRINTED WITH PERMISSION.

REFERENCES

- Allen EP. Use of mucogingival surgical procedures to enhance esthetics. Dent Clin North Am. 1988;32:307–330.

- Kokich VO Jr, Kiyak HA, Shapiro PA. Comparing the perception of dentists and lay people to altered dental esthetics. J Esthet Dent. 1999;11:311–324.

- Tjan AH, Miller GD, The JG. Some esthetic factors in a smile. J Prosthet Dent. 1984;51:24–28.

- Vig RG, Brundo GC. The kinetics of anterior tooth display. J Prosthet Dent. 1978;39:502–504.

- Livada R, Shiloah J. Gummy smile: could it be genetic? Hereditary gingival fibromatosis. J Tenn Dent Assoc. 2012;92:23–26

- Goldman HM, Cohen DW. Periodontal Therapy. 4 ed. St. Louis: C.V. Mosby Company; 1968.

- Volchansky A, Cleaton-Jones PE. Delayed passive eruption. A predisposing factor to Vincent’s infection? J Dent Asso S Africa. 1974;29:291–294.

- Coslet GJ, Vanarsdall R, Weisgold A. Diagnosis and classification of delayed passive eruption of the dentogingival junction in the adult. AlphaOmegan. 1977;10:24–28.

- Ribeiro FS, Castro Garção FC, Martins AT, et al.A modified technique that decreases the height of the upper lip in the treatment of gummy smile patients: a case series study. J Dent Oral Hyg. 2012;4:21–28.

- Ezquerra F, Berrazueta MJ, Ruiz-Capillas A, Arregui JS. New approach to the gummy smile. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1999;104:1143–1150.

- Polo M. Botulinum toxin type A (Botox) for the neuromuscular correction of excessive gingival display on smiling (gummy smile). Am JOrthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2008;133:195–203.Simon Z, Rosenblat A, Dorfman W.Eliminating a gummy smile by surgical liprepositioning. J Cosmetic Dent. 2007;23:100–108.

- Humayun N, Kolhatkar S, Souiyas J, Bhola M.Mucosal coronally positioned flap for themanagement of excessive gingival display in thepresence of hypermobility of the upper lip andvertical maxillary excess: a case report. JPeriodontol. 2010;81:1858–1863.

- Peck S, Peck L. Facial realities and oralesthetics. In: McNamara JA, ed. Esthetics and theTreatment of Facial Form, Vol 28, CraniofacialGrowth Series. Ann Arbor, Mich: Center forHuman Growth and Development; 1993:77–113.

- Kawamoto HK Jr. Treatment of the elongatedlower face and the gummy smile. Clin Plast Surg.1982;9:479–489.

- Garber DA, Salama MA. The aesthetic smile:diagnosis and treatment. Periodontol 2000.1996;11:18–28.

- Kokich V. Esthetics and anterior toothposition: an orthodontic perspective. Part II:Vertical position. J Esthet Dent. 1993;5:174–178.

- Redlich M, Mazor Z, Brezniak N. Severe highAngle Class II Division 1 malocclusion withvertical maxillary excess and gummy smile: acase report. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop.1999;116:317–320.

-

From Dimensions of Dental Hygiene. March 2013; 11(3): 54–56, 59.