Exploring Prevalence And Prevention

What the research shows on the prevalence of chronic periodontitis and the efficacy of traditional prevention interventions.

This course was published in the May 2015 issue and expires May 31, 2018. The author has no commercial conflicts of interest to disclose. This 2 credit hour self-study activity is electronically mediated.

EDUCATIONAL OBJECTIVES

After reading this course, the participant should be able to:

- Discuss the global and national prevalence of chronic periodontitis.

- Identify the three levels of prevention in health care.

- Explain the roles of professional and self-care in the prevention of chronic periodontitis.

INTRODUCTION

The burden of periodontal diseases in the United States is significant, and data show that periodontitis is one of the most prevalent noncommunicable chronic diseases—making it a serious public health concern. National initiatives to control and prevent periodontal diseases should include oral health promotion and disease-prevention strategies based on common risk factors. This article provides a summary of periodontal disease classifications, as well as an overview of risk factors and prevention strategies for periodontitis. The author places special emphasis on evidence-based approaches to professional and self-care therapies that will help guide clinicians and patients to better outcomes. The Colgate-Palmolive Company is delighted to have provided an unrestricted educational grant to support this article in an educational series created in collaboration with the American Academy of Periodontology.

—Matilde Hernandez, DDS, MS, MBA

Dental Science Liaison

Colgate Oral Pharmaceuticals

FROM THE AMERICAN ACADEMY OF PERIODONTOLOGY

As the adage goes, an ounce of prevention is worth a pound of cure. Periodontal diseases are no exception. Dental professionals have a responsibility not only to effectively treat periodontitis, but to investigate its causes, as well as strategies for arresting its progression. As noted in the article, “Exploring Prevalence and Prevention,” understanding periodontitis requires insight into the many factors that contribute to its onset. Investigating the prevalence of periodontal diseases is a priority for the American Academy of Periodontology (AAP). Since 2003, the AAP has worked with the United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention to measure periodontal incidence and prevalence among American adults. Recent findings demonstrate that one out of two US adults older than 30 has some form of periodontal disease—that’s 64.7 million Americans. These numbers indicate a need for public awareness and improved access to care, and they highlight the importance of a dental team well-versed in periodontal disease prevention and treatment. As a part of its commitment to collaborative care, the AAP is proud to work with Dimensions of Dental Hygiene and Colgate-Palmolive to provide the latest from the frontlines of periodontal disease prevention.

—Joan Otomo-Corgel, DDS, MPH,

President, American Academy of Periodontology

Assistant Clinical Professor, University of California, Los Angeles School of Dentistry

Periodontal diseases refer to all of the disorders that affect the gingiva and supporting structures of the teeth—mainly the cementum, periodontal ligament fibers, and alveolar bone.1–3 These can range from inflammation of the gingiva (gingivitis) due to the accumulation of bacterial biofilms on the tooth surfaces to the abnormal growth of gingiva by proliferation of cancer cells. The most prevalent periodontal diseases are dental plaque-induced gingivitis and chronic periodontitis. The American Academy of Periodontology’s (AAP) Glossary of Periodontal Terms defines chronic periodontitis as “an infectious disease resulting in inflammation within the supporting tissues of the teeth, progressive attachment and bone loss that is characterized by pocket formation and/or gingival recession.”2 The AAP notes that chronic periodontitis is prevalent among adults, but can affect individuals at any time.2 As oral health professionals well know, periodontal diseases are related to plaque and calculus and while clinical attachment loss usually advances slowly, rapid progression is also possible.2 The broad term “periodontal diseases” has been historically used interchangeably with the common but distinct disease entities of plaque-induced gingivitis and chronic periodontitis. This is often misleading and may undermine the scope of periodontology.

Periodontal diseases refer to all of the disorders that affect the gingiva and supporting structures of the teeth—mainly the cementum, periodontal ligament fibers, and alveolar bone.1–3 These can range from inflammation of the gingiva (gingivitis) due to the accumulation of bacterial biofilms on the tooth surfaces to the abnormal growth of gingiva by proliferation of cancer cells. The most prevalent periodontal diseases are dental plaque-induced gingivitis and chronic periodontitis. The American Academy of Periodontology’s (AAP) Glossary of Periodontal Terms defines chronic periodontitis as “an infectious disease resulting in inflammation within the supporting tissues of the teeth, progressive attachment and bone loss that is characterized by pocket formation and/or gingival recession.”2 The AAP notes that chronic periodontitis is prevalent among adults, but can affect individuals at any time.2 As oral health professionals well know, periodontal diseases are related to plaque and calculus and while clinical attachment loss usually advances slowly, rapid progression is also possible.2 The broad term “periodontal diseases” has been historically used interchangeably with the common but distinct disease entities of plaque-induced gingivitis and chronic periodontitis. This is often misleading and may undermine the scope of periodontology.

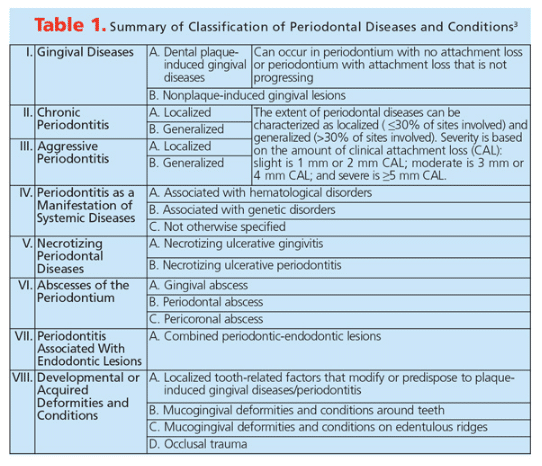

An international expert consensus developed a classification of periodontal diseases in 1999 that is still used today.3 Classifying periodontal diseases enables clinicians to create a framework for appropriate diagnosis and detection of etiology and risk factors. Through this understanding, oral health professionals can direct appropriate treatment for the management of periodontal diseases. Table 1 summarizes these classifications.3

CHRONIC PERIODONTITIS DEFINED

Despite the progress that has been made in understanding chronic periodontitis, prevention, early diagnosis, and management remain a challenge.4 The etiology, onset, development, progress, dormancy and active stages of periodontitis interconnect with the external environment and the internal (host) environment.5–10 External environment factors include access to health care and education; socioeconomic status; diet; tobacco and alcohol use; and microorganisms such as viruses. The internal environment refers to genetic factors; the risk of systemic diseases such as diabetes; immune response, including normal, hypo- and hyper-responses; autoimmunity; microorganisms; and foreign bodies, such as dental prostheses and implants.

Chronic periodontitis is an ongoing inflammatory disease that ultimately causes tooth loss by destroying the supporting tissues whenever there is dysbiosis (alterations in the makeup of resident commensal communities) between external and internal environmental factors. This dysbiosis varies between individuals and can change between adjacent teeth in the same patient.11,12

PREVALENCE AND INCIDENCE OF PERIODONTITIS

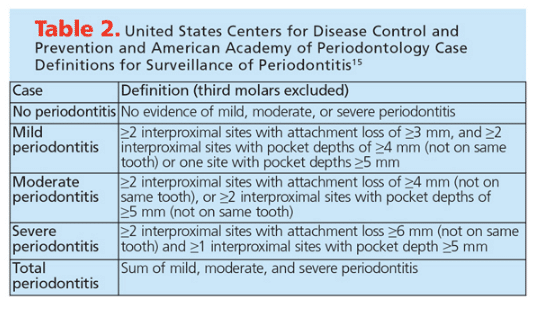

The term prevalence refers to the number of disease cases existing in a given population at a specific time (period prevalence) or at a particular moment in time (point prevalence).1 Incidence refers to the number of new events, such as people falling ill with a specified disease during a certain period within one population.1 Historically, the prevalence of periodontal diseases has been incorrectly noted due to differences in case definitions and measurement of clinical parameters. Recently, the Joint European Union and United States Periodontal Epidemiology Working Group created standards for reporting chronic periodontitis prevalence and severity in epidemiologic studies.13 Members of the group have proposed the inclusion of study design; periodontal recording protocol with specific teeth sites, probing pressure, thickness, and graduation; medical history such as diabetes and body mass index; and specific clinical parameters such as clinical attachment level, probing depth, and the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention/AAP case definition (Table 2).14,15

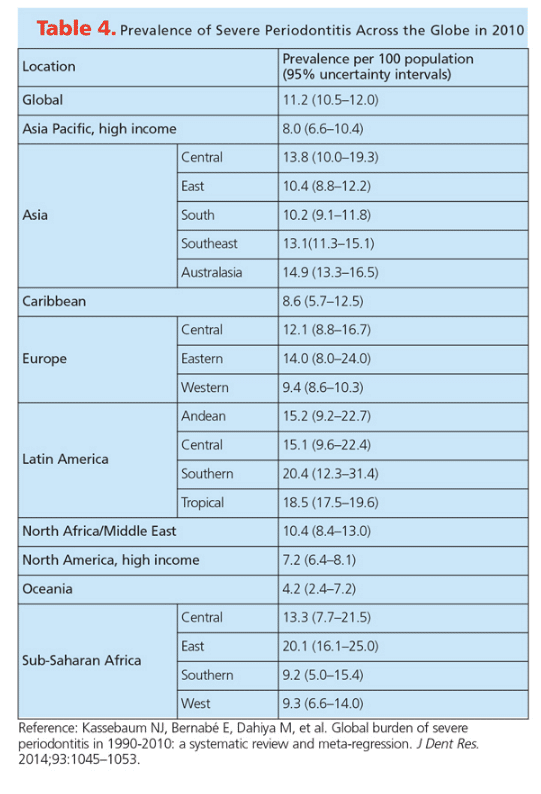

Severe periodontitis, which affects more than 740 million people, is considered the sixth most prevalent disease in the world.16 Between 1990 and 2010, the global age standardized prevalence of severe periodontitis was estimated at 11.2%.16 The highest prevalence was noted in Latin America, with figures ranging between 15.1% and 20.4%.16 East Sub-Saharan Africa also had a high prevalence of 20.1%.16 Some regions in Asia and Europe had prevalence above the global standard, including Eastern Europe at 14% and Australasia at 14.9%. The lowest prevalence was noted in Oceania at 4.2%. The prevalence of severe periodontitis in North America was 7.2%.16

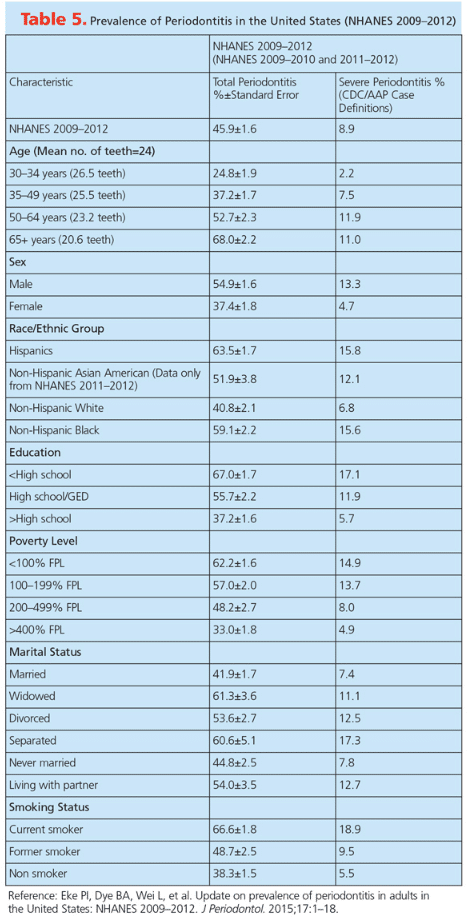

Data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) during 2009-2010 and 2011-2012 provided an update on the prevalence of periodontitis in the US adult population.17 It is estimated that about 64.7 million American adults have periodontitis (46%).17 Among the 46%, about 8.9% have severe periodontitis. Distribution among races in the US was as follows: Hispanics, 63.5%; NonHispanic blacks, 59.1%; NonHispanic Asian Americans, 50%; and NonHispanic whites, 40.8%. Low socioeconomic status, low education levels, and increasing age were all associated with an increased prevalence. The NHANES utilized the full-mouth periodontal examination for measuring probing pocket depths and clinical attachment levels at six sites per tooth in all teeth except the third molars. The authors predict, however, that the numbers provided may be an underestimate due to the exclusion of institutionalized individuals and people with certain medical conditions, third molars, furcation detection, and bleeding on probing.

RISK FACTORS FOR CHRONIC PERIODONTITIS

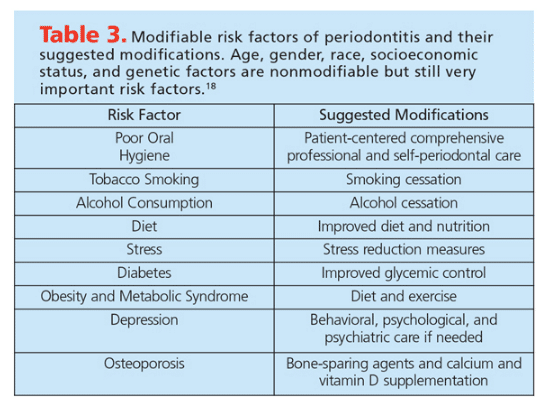

The risk factors for chronic periodontitis include gender, smoking history, alcohol use, diabetes, obesity, metabolic syndrome, osteoporosis, low levels of dietary calcium and vitamin D, stress, and genetic factors, many of which are modifiable (Table 3).18 These risk factors are also shared with other chronic systemic diseases such as cardiovascular disease, cancer, arthritis, and stroke.19,20 It is estimated that approximately 117 million American adults have one or more chronic health conditions.19 Most of the risk factors for chronic diseases—including chronic periodontitis—are modifiable; thus, management of chronic periodontitis follows the same approach as any chronic disease.

THE UPSTREAM APPROACH TO PREVENTING CHRONIC PERIODONTITIS

There are three levels of prevention recognized in health care: primary, secondary, and tertiary prevention. Avoiding disease is the basis of primary prevention, while secondary prevention focuses on interfering with the disease process before signs and symptoms appear.1 Finally, tertiary prevention relates to avoiding the consequences of disease progression.1

In regards to chronic periodontitis, primary prevention is the maintenance of oral health with no disease present. Secondary prevention refers to the management of plaque-induced gingivitis and/or risk factors for chronic periodontitis via nonsurgical and surgical therapies to prevent chronic periodontitis. Tertiary prevention is the management of patients with chronic periodontitis through nonsurgical and surgical therapy and maintenance to avoid further damage by the disease process.

There are two primary ways to reduce the prevalence of plaque-induced gingivitis and chronic periodontitis. The first is to implement personalized prevention and a therapeutic plan based on scientific evidence, clinical experience, and patient circumstances and preferences in populations with access to professional dental care and communities with limited availability of services. The second strategy is to conduct high-quality scientific research in the epidemiology, etiology, risk assessment, pathogenesis, treatment, and prevention of gingivitis and chronic periodontitis so that the first approach can be consistently improved.

Prevention is most simple among individuals who are intrinsically motivated toward health maintenance. The challenge is to promote prevention among those who do not adhere to regular oral health measures, which typically falls low on the priority list in people’s daily lives. In populations where factors such as low socioeconomic status, lack of education, and limited access to care are prevalent, prevention is unlikely. While much research is conducted on the efficacy of chronic periodontitis treatment, the long-term successful management of dental plaque-induced gingivitis and chronic periodontitis is possible only by prevention via the upstream approach. This approach focuses on the risk factors that trigger the onset, sustain the development, resist conventional treatment, and encourage the recurrence of well-managed chronic disease.21,22 The reasons certain people develop chronic periodontitis despite being diligent in oral self-care remain unclear.

Prevention is most simple among individuals who are intrinsically motivated toward health maintenance. The challenge is to promote prevention among those who do not adhere to regular oral health measures, which typically falls low on the priority list in people’s daily lives. In populations where factors such as low socioeconomic status, lack of education, and limited access to care are prevalent, prevention is unlikely. While much research is conducted on the efficacy of chronic periodontitis treatment, the long-term successful management of dental plaque-induced gingivitis and chronic periodontitis is possible only by prevention via the upstream approach. This approach focuses on the risk factors that trigger the onset, sustain the development, resist conventional treatment, and encourage the recurrence of well-managed chronic disease.21,22 The reasons certain people develop chronic periodontitis despite being diligent in oral self-care remain unclear.

Despite efforts made in primary and secondary prevention, millions of people are still affected by chronic periodontitis. Acute, reversible diseases are usually treated or cured. Chronic diseases are managed so that additional damage to the host is prevented. However, it takes just one risk factor or etiological agent to tip the homeostatic state toward the dysbiotic state. Hence, management is key for chronic diseases. Periodontal maintenance is not only removing bacterial biofilm through scaling and root planing, it is the comprehensive reevaluation of external and internal factors that may cause a shift in the balance, causing disease.

Much of the available evidence on the prevention of chronic periodontitis is moderate to weak.23 Cochrane Oral Health Group publishes high-quality systematic reviews that are considered the highest level of evidence to guide clinical decision making in oral health. As of March 2015, 14 systematic reviews have been published by the Cochrane Group on preventive care for periodontal diseases.24–37 These reviews demonstrate that the majority of preventive care strategies are not supported by high-level scientific evidence. However, these papers can guide clinicians in the evidence-based clinical decision-making process. For example, Worthington et al25 found there was insufficient evidence to determine whether the effects of routine scaling and prophylaxis on patients without risk factors for oral disease were beneficial enough to support the dental practice’s traditional recare schedule. Another review by Riley and Lamont26 determined that toothpaste containing triclosan/copolymer, in combination with fluoride, reduced plaque, gingival inflammation, and gingival bleeding compared to toothpastes containing only fluoride. Harris et al37 also published a Cochrane review in which they found that one-one-one interventions regarding diet and nutrition in the dental office may lead to behavior changes, although they noted that additional evidence is needed to support their conclusions.

PROFESSIONAL AND SELF-CARE

Long-term studies have clearly shown the benefit of professional mechanical plaque removal on long-term periodontal health and maintenance.38 Drisko’s39 review of the effects of self-care on periodontal health found that interproximal devices, specifically interproximal brushes, reduced more interproximal plaque and gingivitis than flossing or toothbrushing alone. There is also some evidence demonstrating that power toothbrushes provide greater benefits than manual toothbrushes.39

A series of consensus papers based on the proceedings of the XI European Workshop in Periodontology provides additional evidence on prevention strategies. The reports were written by an expert group of European professionals and were also endorsed by the American Academy of Periodontology (AAP). These reviews were based on conclusions derived from the available best evidence (16 systematic reviews and meta-analyses of the systematic reviews) and supplemented by expert recommendations whenever the evidence was unavailable, weak, or inconclusive.40–55 The same workshop also published a series of papers on peri-implant health and disease.56,57

The key consensus conclusions on the effective prevention of periodontal and peri-implant diseases include:41

- An appropriate periodontal diagnosis is needed before patients undergo preventive measures and should determine the type of preventive care selected

- Preventive measures are not a substitute for the treatment of periodontitis

- Consistent and personalized oral hygiene instruction, as well as professional periodontal debridement are key components of a preventive program

- Behavioral strategies to improve oral hygiene should set specific goals and incorporate planning and self-monitoring

- Short interventions to control risk factors are necessary parts of primary and secondary periodontal prevention

- Evidence-based periodontal risk assessment tools should be used to classify patients by their risk of disease progression and tooth loss

Chapple et al46 summarized the evidence on the primary prevention of chronic periodontitis by preventing gingivitis. They specifically examined four approaches: mechanical self-administered plaque-control regimens; self-administered interdental mechanical plaque control; adjunctive chemical plaque control; and anti-inflammatory (sole or adjunctive) approaches. Based on four reviews (two meta-reviews and two systematic reviews), the recommendations for the management of gingivitis that improved health outcomes in general included: professionally administered plaque control, reinforcement of oral hygiene, toothbrushing with rechargeable power toothbrushes, interproximal cleaning with interdental brushes, flossing only where interdental brushes cannot access without causing trauma, and adjunctive use of chemical plaque-control agents.

With regards to method, frequency, and duration of toothbrushing in patients with gingivitis, the consensus was to recommend toothbrushing for 2 minutes twice daily with a fluoride dentifrice. The panel noted, however, that 2 minutes is inadequate for patients with chronic periodontitis. Also, interdental cleaning was recommended once per day for patients with gingivitis. Finally, the panel concluded that there was not enough evidence to support a consensus recommendation on the use of local or systemic anti-inflammatory agents for gingivitis.

Sanz et al51 summarized the evidence on four topics: the result of scaling and root planing on the secondary prevention of periodontal diseases; presence of gingival recession and noncaries cervical lesions secondary to trauma caused by toothbrushing; addressing the pain of dentinal hypersensitivity through professional and over-the-counter remedies; and the treating of breath malodor through mechanical and/or chemical means. The mean tooth loss rates of patients who underwent supportive periodontal therapy, including professional mechanical plaque removal, were 0.15 ± 0.14 teeth/year at the 5-year follow-up and 0.09 ± 0.08 teeth/year or 1.1 to 1.3 teeth lost in the follow-up period of 12 years to 14 years. The authors did not find any evidence that toothbrushing (either with manual or power toothbrushes) caused gingival recession or noncaries cervical lesions but reported that local and patient factors may play a role in the development of these oral health problems. Dentifrices that contain stannous fluoride, calcium sodium phosphosilicate, arginine, and strontium seem to provide pain relief caused by dentinal hypersensitivity, as do prophylaxis pastes containing calcium sodium phosphosilicate and arginine. Tongue cleaning and mouthrinses containing chlorhexidine, cetylpyridinium chloride, and zinc help reduce oral malodor.

CONCLUSION

Chronic disease prevention is simple with compliant and motivated patients. Achieving the same results, however, in a large population with varying environmental, socioeconomic, cultural, and lifestyle factors is daunting, but not impossible. Oral health professionals should heed the recommendations made by the XI European Workshop in Periodontology’s proceedings, which focus on overall health promotion that benefits oral health, including:

- Teaching the public that gingival bleeding is an early sign of disease

- Implementing periodontal screening by dental professionals

- Importance of oral health professionals in promoting health and in the primary and secondary prevention of disease

- Noting the limitations of self-treatment before diagnosis of disease has occurred

- Improving access to professional preventive care

BONUS WEB CONTENT

![Prevalence of Chronic Periodontitis]() ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The author would like to thank Kativa Strickland; Antonia Teruel, DDS, MS, PhD; and Sarah Bushehri, BDS, MFDS, for their help with this manuscript. In addition, the author would like to express his gratitude to all of the authors whose work has furthered the understanding of periodontal diseases and to the American Academy of Periodontology Foundation for supporting his career in academia.

REFERENCES

- Stedman’s Medical Dictionary. 28th ed. Baltimore: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2006.

- Glossary of Periodontal Terms. Chicago: American Academy of Periodontology; 2001.

- Armitage GC. Development of a classification system for periodontal diseases and conditions. Ann Periodontol. 1999;4:1–6.

- Armitage GC. Learned and unlearned concepts in periodontal diagnostics: a 50-year perspective. Periodontol 2000. 2013;62:20–36.

- Petersen C, Round JL. Defining dysbiosis and its influence on host immunity and disease. Cell Microbiol. 2014;16:1024–1033.

- Teles R, Teles F, Frias-Lopez J, Paster B, Haffajee A. Lessons learned and unlearned in periodontal microbiology. Periodontol 2000. 2013;62:95–162.

- Ebersole JL, Dawson DR 3rd, Morford LA, Peyyala R, Miller CS, Gonzaléz OA. Periodontal disease immunology: ‘double indemnity’ in protecting the host. Periodontol 2000. 2013;62:163–202.

- Bartold PM, Van Dyke TE. Periodontitis: a host-mediated disruption of microbial homeostasis. Unlearning learned concepts. Periodontol 2000. 2013;62:203–217.

- Darveau RP, Hajishengallis G, Curtis MA. Porphyromonas gingivalis as a potential community activist for disease. J Dent Res. 2012;91:816–820.

- Hajishengallis G. Periodontitis: from microbial immune subversion to systemic inflammation. Nat Rev Immunol. 2015;15:30–44.

- Ursell LK, Clemente JC, Rideout JR, Gevers D, Caporaso JG, Knight R. The interpersonal and intrapersonal diversity of human-associated microbiota in key body sites. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2012;129:1204–1208.

- Costalonga M, Herzberg MC. The oral microbiome and the immunobiology of periodontal disease and caries. Immunol Lett. 2014;162:22–38.

- Holtfreter B, Albandar JM, Dietrich T, et al. Standards for reporting chronic periodontitis prevalence and severity in epidemiologic studies Proposed standards from the Joint EU/USA Periodontal Epidemiology Working Group. J Clin Periodontol. March 23, 2015. Epub ahead of print.

- Page RC, Eke PI. Case definitions for use in population-based surveillance of periodontitis. J Periodontol. 2007;78:1387–1399.

- Eke PI, Page RC, Wei L, Thornton-Evans G, Genco RJ. Update of the case definitions for population-based surveillance of periodontitis. J Periodontol. 2012; 83:1449–1454.

- Kassebaum NJ, Bernabé E, Dahiya M, Bhandari B, Murray CJ, Marcenes W. Global burden of severe periodontitis in 1990-2010: a systematic review and meta-regression. J Dent Res. 2014;93:1045–1053.

- Eke PI, Dye BA, Wei L, Slade GD, et al. Update on prevalence of periodontitis in adults in the United States: NHANES 2009-2012. J Periodontol. 2015;17:1–18.

- Genco RJ, Borgnakke WS. Risk factors for periodontal disease. Periodontol 2000. 2013;62:59–94.

- Ward BW, Schiller JS, Goodman RA. Multiple chronic conditions among US adults: a 2012 update. Prev Chronic Dis. 2014;11:130389.

- Cullinan MP, Seymour GJ. Periodontal disease and systemic illness: will the evidence ever be enough? Periodontol 2000. 2013;62:271–286.

- Choucair B, Bhatt JD. A new era for population health: government, academia, and community moving upstream together. Am J Public Health. 2015;105 Suppl 2:S144.

- Baelum V. Dentistry and population approaches for preventing dental diseases. J Dent. 201;39(Suppl 2):S9–S19.

- The Cochrane Collaboration. Oral Health Group. Available at: ohg.cochrane.org. Accessed April 13, 2015.

- Li C, Lv Z, Shi Z, et al. Periodontal therapy for the management of cardiovascular disease in patients with chronic periodontitis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;8:CD009197.

- Worthington HV, Clarkson JE, Bryan G, Beirne PV. Routine scale and polish for periodontal health in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;11:CD004625.

- Riley P, Lamont T. Triclosan/copolymer containing toothpastes for oral health. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;12:CD010514.

- Poklepovic T, Worthington HV, Johnson TM, et al. Interdental brushing for the prevention and control of periodontal diseases and dental caries in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;12:CD009857.

- Esposito M, Grusovin MG, Worthington HV. Interventions for replacing missing teeth: treatment of peri-implantitis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;1:CD004970.

- Sambunjak D, Nickerson JW, Poklepovic T, et al. Flossing for the management of periodontal diseases and dental caries in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011;12:CD008829.

- Simpson TC, Needleman I, Wild SH, Moles DR, Mills EJ. Treatment of periodontal disease for glycemic control in people with diabetes. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010;5:CD004714.

- Grusovin MG, Coulthard P, Worthington HV, George P, Esposito M. Interventions for replacing missing teeth: maintaining and recovering soft tissue health around dental implants. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010;8:CD003069.

- Deacon SA, Glenny AM, Deery C, et al. Different powered toothbrushes for plaque control and gingival health. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 20108;12:CD004971.

- Eberhard J, Jepsen S, Jervøe-Storm PM, Needleman I, Worthington HV. Full-mouth disinfection for the treatment of adult chronic periodontitis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2008;1:CD004622.

- Renz A, Ide M, Newton T, Robinson PG, Smith D. Psychological interventions to improve adherence to oral hygiene instructions in adults with periodontal diseases. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007;2:CD005097.

- Yaacob M, Worthington HV, Deacon SA, et al. Powered versus manual toothbrushing for oral health. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;6:CD002281.

- Riley P, Worthington HV, Clarkson JE, Beirne PV. Recall intervals for oral health in primary care patients. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;12:CD004346.

- Harris R, Gamboa A, Dailey Y, Ashcroft A. One-to-one dietary interventions undertaken in a dental setting to change dietary behaviour. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;3:CD006540.

- Axelsson P, Nyström B, Lindhe J. The long-term effect of a plaque control program on tooth mortality, caries and periodontal disease in adults. Results after 30 years of maintenance. J Clin Periodontol. 2004;31:749–757.

- Drisko CL. Periodontal self-care: evidence-based support. Periodontol 2000. 2013;62:243–255.39.

- Tonetti MS, Chapple IL, Jepsen S, Sanz M. Primary and Secondary Prevention of Periodontal and Peri-Implant Diseases Introduction to, and Objectives of the Consensus from the 11th European Workshop on Periodontology. J Clin Periodontol. Feb 12, 2015 . Epub ahead of print.

- Tonetti MS, Eickholz P, Loos BG, et al. Principles in prevention of periodontal diseases. J Clin Periodontol. Jan 29, 2015. Epub ahead of print.

- Needleman I, Nibali IL, Di Iorio A. Professional mechanical plaque removal for prevention of periodontal diseases in adults—systematic review update. J Clin Periodontol. March 2015. Epub before print.

- Newton JT, Asimakopoulou K. Managing oral hygiene as a risk factor for periodontal disease: a systematic review of psychological approaches to behaviour change for improved plaque control in periodontal management. J Clin Periodontol. March 31, 2015. Epub ahead of print.

- Ramseier CA, Suvan JE. Behaviour change counselling for tobacco use cessation and promotion of healthy lifestyles: a systematic review. J Clin Periodontol. March 31, 2015. Epub ahead of print.

- Lang NP, Suvan JE, Tonetti MS. Risk factor assessment tools for the prevention of periodontitis progression a systematic review. J Clin Periodontol. March 31, 2015. Epub ahead of print.

- Chapple IL, Van der Weijden F, Dorfer C, et al. Primary prevention of periodontitis: managing gingivitis. J Clin Periodontol. Jan 29, 2015. Epub ahead of print.

- Van der Weijden FA, Slot DE. Efficacy of homecare regimens for mechanical plaque removal in managing gingivitis a meta review. J Clin Periodontol. March, 31 2015. Epub ahead of print.

- Sälzer S, Slot DE, Van der Weijden FA, Dörfer CE. Efficacy of inter-dental mechanical plaque control in managing gingivitis—a meta-review. J Clin Periodontol. March 31, 2015. Epub ahead of print.

- Serrano J, Escribano M, Roldán S, Martín C, Herrera D. Efficacy of adjunctive anti-plaque chemical agents in managing gingivitis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Clin Periodontol. March 31, 2015. Epub ahead of print.

- Polak D, Martin C, Sanz-Sánchez I, Beyth N, Shapira L. Are anti-inflammatory agents effective in treating gingivitis as solo or adjunct therapies? A systematic review. J Clin Periodontol. March 31, 2015. Epub ahead of print.

- Sanz M, Bäumer A, Budunelli N, et al. Effect of professional mechanical plaque removal on secondary prevention of periodontitis and the complications of gingival and periodontal preventive measures. J Clin Periodontol. Jan 27, 2015. Epub ahead of print.

- Trombelli L, Franceschetti G, Farina R. Effect of professional mechanical plaque removal performed on a long-term, routine basis in the secondary prevention of periodontitis: a systematic review. J Clin Periodontol. March 31, 2015. Epub ahead of print.

- Heasman PA, Holliday R, Bryant A, Preshaw PM. Evidence for the occurrence of gingival recession and non-carious cervical lesions as a consequence of traumatic toothbrushing. J Clin Periodontol. March 31, 2015. Epub ahead of print.

- West NX, Seong J, Davies M. Management of dentine hypersensitivity: efficacy of professionally and self-administered agents. J Clin Periodontol. March 31, 2015. Epub ahead of print.

- Slot DE, De Geest S, van der Weijden FA, Quirynen M. Treatment of oral malodor. Medium-term efficacy of mechanical and/or chemical agents: a systematic review. J Clin Periodontol. March 31, 2015. Epub ahead of print.

- Derks J, Tomasi C. Peri-implant health and disease. A systematic review of current epidemiology. J Clin Periodontol. March 31, 2015. Epub ahead of print.

- Schwarz F, Becker K, Sager M. Efficacy of professionally administered plaque removal with or without adjunctive measures for the treatment of peri-implant mucositis. A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Clin Periodontol. 2015. March 31, 2015. Epub ahead of print.

From Dimensions of Dental Hygiene. May 2015;13(5):53–59.