ALEXANDERFORD / E+/ GETTY IMAGES PLUS

ALEXANDERFORD / E+/ GETTY IMAGES PLUS

Every Practice Needs an Infection Control Coordinator

Adding this position to the dental team is key to ensuring safety and compliance in the dental setting.

In 2016, the United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) published a “Summary of Infection Prevention Practices in Dental Settings, Basic Expectations for Safe Care,” which formalized the recommendation that every dental practice should have an infection control coordinator (ICC).1 The 2016 CDC document recommended that “at least” one person in the office be responsible for everything related to infection control and prevention.1 This included maintaining knowledge or training in infection control, creating evidence-based written infection control policies and procedures based on regulatory and guidance documents, ensuring compliance with current guidance, making sure proper and adequate supplies and equipment are available, and providing communication related to infection control and prevention to everyone in the practice.1 Seven years later, knowledge and compliance with the recommendation for an ICC still appears low.

The initial recommendation for an ICC is implied in the CDC’s comprehensive “Guidelines for Infection Control in Dental Health-Care Settings-2003.”2 The 2003 CDC document discusses the need for personnel health elements as part of infection control programs. These elements include education for oral health professionals, identifying risks in the workplace, providing safe procedures, and supplying prompt exposure management.2 The 2003 document suggests that ICCs should consult with other healthcare providers to attain the goal of meeting and establishing personnel health elements, as dental practices do not have licensed medical staff to provide such programs.2

Since the publication of the 2003 CDC document, many changes in dental infection control and prevention have occurred, so it is vital to appoint a designated ICC. An ICC has the knowledge and skills to ensure safety and compliance for patients and staff.

Getting Started

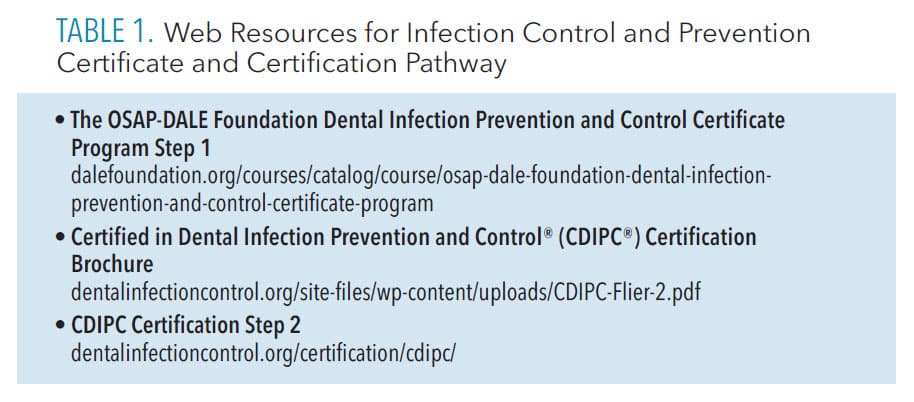

Currently, there are two avenues ICCs can explore if they desire additional knowledge and credentials: a formalized infection control and prevention certificate program and an official certification.3 The certificate program and certification pathway are a joint effort between the Dental Assisting National Board, Dental Advancement Through Learning and Education (DALE) Foundation, and Organization for Safety Asepsis and Prevention (OSAP).

The OSAP-DALE Foundation Dental Infection Prevention and Control Certificate Program is a comprehensive educational program intended for all dental personnel.3 The certificate program includes two major components: completing nine chapters of coursework and an exam. Obtaining the certificate is the first step toward further certification.

The Certified in Dental Infection Prevention and Control® (CDIPC) is an advanced certification that provides a formal credential.4 Several steps are needed to complete it, including an examination taken at a testing center, much like a board examination.

Obtaining a formal credential demonstrates that oral health professionals are competent to provide the proper education, training, monitoring, compliance, planning, and tracking necessary to meet the personnel health elements of the CDC guidelines (2003 and 2016).1,2 Obtaining the certificate or CDIPC credential is an excellent choice for ICCs. Table 1 provides more information.

Dental Hygienists Fit the Bill

Dental hygienists are ideal candidates to serve as ICCs because they have an extensive background in infection control and prevention through their formal education, which requires meeting specific competencies (Standard 5-1) set forth by the Commission on Dental Accreditation.5 All ICCs must have comprehensive knowledge of infection control policies, procedures, guidance recommendations, and regulatory requirements.

Many clinicians have questions about where to start when appointed to the role of ICC. The ICC is responsible for ensuring that compliance is achieved and maintained, remaining knowledgeable about the subject, serving as the contact point for exposure incidents, providing training for all staff members, and making arrangements for staff to receive post-exposure follow up care.

Individuals new to the role of ICC should start by becoming familiar with the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) standards and requirements, as well as dental infection control guidelines provided by the CDC.1, 2 It is also prudent to collect additional resources for infection control training and instruction.

Occupational Health and Safety Administration

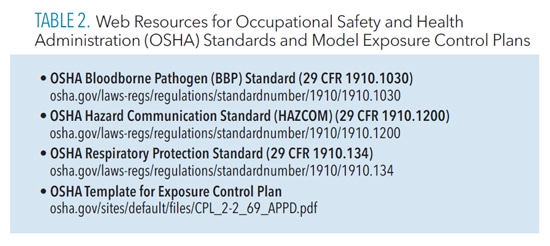

The OSHA is an agency within the US Department of Labor launched in 1971 to ensure workplace safety.6 As a regulatory agency, OSHA has enforcement capabilities, meaning it can investigate and impose fines. Dental offices must adhere to the OSHA Bloodborne Pathogen (BBP) Standard (29 CFR 1910.1030),7 the Hazard Communication (HAZCOM) Standard (29 CFR 1910.1200),8 and the Respiratory Protection Standard (29 CFR 1910.134).9

The OSHA BBP standard focuses on preventing the exposure of at-risk employees (those who have the potential for exposure to blood or other potentially infectious material) to bloodborne pathogens such as hepatitis B, hepatitis C, and human immunodeficiency virus. The OSHA BBP standard requires employers to comply with several requirements.

First, employers must have an exposure control plan, which is a site-specific document that demonstrates how the office complies with OSHA standards. The plan must include: a copy of the OSHA BBP standard; a list that determines job categories in which employees might have exposure to BBPs; and how the office implements methods of exposure control, such as universal/standard precautions, engineering and work practice controls, personal protective equipment (PPE), housekeeping, employee hepatitis B vaccination records, post-exposure evaluations and follow-up, how hazards are communicated to employees, documentation of training, and record keeping. The exposure control plan must be updated at least annually.7

The OSHA BBP standard also states that employers must ensure employees use standard precautions, engineering controls (safety devices), and work practice controls (safe behaviors). They must provide PPE, such as gloves, masks, eye protection, and protective attire (gowns or lab coats) that are laundered either by a service or on-site, so employees do not take contaminated garments home.

Employers are required to offer the hepatitis B vaccine and maintain a post-exposure protocol (outlined in the exposure control plan). Employees have the right to decline the vaccine and post-exposure protocol, but they should be counseled about the risks associated with declination.

Employers must provide BBP standard training upon hire, when new job tasks with exposure risks are undertaken, and, at least, annually. Finally, employers are required to maintain personal health records for all at-risk employees and documentation of BBP training.7 Training on BBP and record keeping are primary duties of the ICC.

By Kandis V. Garland, RDH, MS

For aerosol-generating procedures, the CDC recommends the use of standard precautions, N95 respirator instead of a surgical face mask, eye protection, gown or other protective clothing, and gloves. Gowns or protective clothing, such as a lab coat, should be changed after each patient, discarded if disposable, or laundered if cloth.1

For aerosol-generating procedures, the CDC recommends the use of standard precautions, N95 respirator instead of a surgical face mask, eye protection, gown or other protective clothing, and gloves. Gowns or protective clothing, such as a lab coat, should be changed after each patient, discarded if disposable, or laundered if cloth.1 Masks are a required part of safe care and selection depends on several factors including ASTM level for tasks being performed, comfort, and cost. With N95 respirators, initial fit testing is required.1,2 Users should perform a seal check each time the N95 is donned.1 Masks should be discarded after each patient.1,2 The CDC discourages extended use of N95 respirators. Use of a full face shield along with an N95 is recommended for aerosol-generating procedures.1 It is not necessary to wear a surgical mask over the N95.To learn more about mask selection, read the author’s column “Ensuring Safe Mask Selection” in the June 2021 issue of Dimensions of Dental Hygiene.

References

- United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Guidance for Dental Settings. Interim Infection Prevention and Control Guidance Providing Dental Care During the COVID-19 Pandemic. Available at: cdc.gov/coronavirus/떓-ncov/hcp/dental-settings.html. Accessed December 21, 2022.

- Kohn WG, Collins AS, Cleveland JL, et al. Guidelines for infection control in dental health-care settings—2003. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2003;52(RR-17):1–66.

- American Society for Testing and Materials Standards. ASTM F2100–11. Standard Specification for Performance of Materials Used in Medical Face Masks. Accessed at: astm.org/Standards/F2100.htm. Accessed December 21, 2022.

HAZCOM Standard

Infection control coordinators must also be familiar with the HAZCOM standard,8 which focuses on exposure to chemicals used in the dental office. Employers must implement a HAZCOM program to be OSHA compliant. The employer is required to provide a written description of how the office meets the HAZCOM standard that includes: ensuring that hazardous chemicals contain a label; keeping safety data sheets (SDS) for hazardous chemicals in an easily accessed area; and providing training for employees who work with hazardous chemicals.8

In 2013, the HAZCOM standard was revised and became aligned with the Globally Harmonized System of Classification and Labeling of Chemicals, a worldwide universal labeling system for hazardous materials. This system requires a uniform labeling system with standard language and signal words, product identifiers, hazard statements, and pictorial diagrams for all hazardous materials.

Employers are responsible for storing hazardous materials in their original containers with labels that meet the new standard. If a hazardous material must be moved into a new container, the receptacle must include a label with the same information as the original label, including the correct pictorial diagram.

Manufacturers of hazardous chemicals are responsible for providing SDS when products are ordered. Employers must maintain SDS for each hazardous chemical used in the office and ensure they are always accessible to at-risk employees.8 SDS can be stored digitally or as hard copies. Table 2 includes resources for accessing the standards, a quick reference guide for medical and dental offices, and HAZCOM pictorial diagrams. HAZCOM training and record keeping are primary duties of the ICC.

Respiratory Protection

The OSHA Respiratory Protection Standard requires employers to provide adequate respiratory PPE when dealing with airborne pathogens as part of a comprehensive respiratory program.9 Medical evaluation, fit testing, and mask selection are part of the standard (see sidebar). The ICC can provide fit testing, education, monitoring, and tracking of the respiratory protection standard. Table 2 includes a resource that provides templates for creating an OSHA exposure control plan.10 OSHA is an important resource for all ICCs.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Guidelines

The CDC guidelines1,2 should be consulted often and carefully. They provide recommendations that must be interpreted by the practitioner, and are not always clear. Developing a keen understanding of the guidelines is key to implementing a safe work environment.

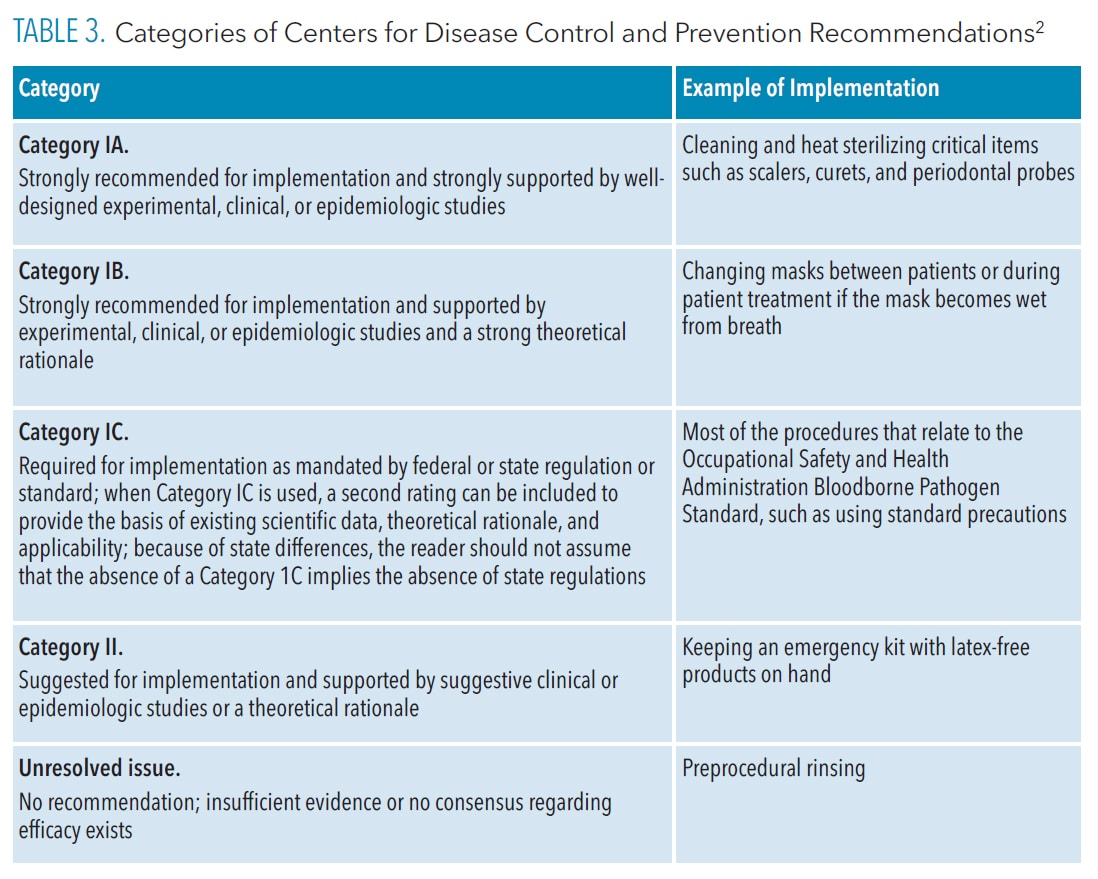

The CDC guidelines contain evidence-based recommendations for infection control procedures that are categorized according to the supporting data, theoretical rationale, and applicability. Several categories of recommendations have been developed by the CDC and the Healthcare Infection Control Practices Advisory Committee (HICPAC). They are Category IA, IB, IC, II, and Unresolved Issue.2 Table 3 provides a summary of these recommendations.

While items in Category IA and IB are both “recommended for implementation and strongly supported by well-designed experimental, clinical, or epidemiologic studies,”2 items in Category IB are also supported by a strong theoretical rationale. An example of a Category 1A item is the cleaning and heat sterilizing of critical items such as scalers, curets, and periodontal probes.

Changing a mask between patients or during patient treatment if the mask becomes wet from the breath is an example of a Category IB item. Category IC recommendations are required by regulation. Items in this category include most of the procedures outlined in the OSHA BBP standard, such as using universal or standard precautions for all patients.

Items in Category II are “suggested for implementation” and supported by suggestive clinical or epidemiological studies or a theoretical rationale. For instance, maintaining an emergency kit with latex-free products is a Category II item. The final category of Unresolved Issue encompasses those items for which the CDC and HICPAC have no recommendation due to a lack of scientific evidence. Preprocedural rinsing falls into this category.2

In review, items in Category IA and Category IB are strongly recommended based on research evidence, but not mandatory. Category IC items are required/mandated (enforceable by OSHA). Items in Category II are suggested but not mandatory, while the Unresolved Issue items are not recommended or mandatory.

The CDC guidelines provide recommendations related to all elements of the BBP standard. They also include guidance for safe practices related to hand hygiene, PPE, latex hypersensitivity, sterilization and disinfection of instruments, storage of instruments, environmental infection control, dental unit waterlines, handpieces, radiology equipment, single-use disposable items, parenteral medications, preprocedural rinsing, handling of biopsy specimens, dental laboratory, laser smoke, and prion diseases. Appendices related to disinfectants and sterilants, recommended immunizations for dental health care workers, and methods for sterilizing and disinfecting surfaces and patient care items are also included.1,2

Compliance

Compliance with infection control guidelines among US dentists varies.11 A study by Cleveland et al11 measured the compliance of US dental offices (n=3,042) with four key CDC recommendations: the presence of an infection control coordinator, maintaining dental unit waterline quality, documenting exposure incidents, and using safe medical devices.

The study found that 34% of practices had implemented zero or one of the four recommendations, 40% had implemented two of the recommendations, and only 26% had implemented three or four of the recommendations. The authors suggested that improved knowledge of infection control procedures in the dental setting was needed. Implementing a variety of teaching methods and increasing continuing education requirements, they advised, may help promote a safe clinical environment.11

A study by Kelsch et al12 suggested mandatory continuing education in infection control along with increased education with infection control to improve compliance and awareness of infection control guidelines. The presence of a designated ICC helps improve compliance and awareness.

Developing a comprehensive understanding of the 2003 and 2016 CDC guidelines is a starting point when determining the infection control compliance level in a dental office. Comparing a dental practice’s infection control protocol to those recommended by the CDC will help dental team members determine their level of compliance.

The 2016 CDC document provides a simple checklist or self-audit to assess compliance.1 Fluent13 describes self-examination as the first and most important step in infection prevention in the dental office. The safe practice of dentistry requires thorough knowledge of guidelines and regulations, strong leadership, self-assessment, regular continuing education and training, and continuous monitoring of compliance.13

The presence of a designated infection control coordinator helps improve compliance and awareness

Additional Resources

Making sense of the CDC guidelines and OSHA standards can be challenging for a new ICC. Fortunately, excellent resources are available. As noted earlier, the OSAP-DALE Foundation certificate or CDIPC certification is one way to obtain comprehensive skills necessary for ICCs.

Additionally, OSAP is an excellent resource. This organization, founded in 1984, is composed of educators, clinicians, researchers, and industry stakeholders who have an interest in infection prevention and safety.14 OSAP’s vision is that “every visit is a safe dental visit,” and its mission is “to be the world’s leading provider of education that supports safe dental visits.”14

OSAP provides publications, checklists, toolkits, educational opportunities, webinars, FAQs, and training materials. Many of the resources are free; however, membership provides additional benefits such as discounts on training materials and continuing education. OSAP is a must-have resource for ICCs.

Professional associations such as the American Dental Hygienists’ Association (ADHA) and the American Dental Association (ADA) are additional resources for information related to infection control and prevention.15,16 The ADHA and ADA offer several publications and provide FAQs and links to infection control resources. The ADA catalog contains an OSHA compliance training kit.

The Association for Professionals in Infection Control and Epidemiology (APIC), whose mission is to “advance the science and practice of infection prevention and control” is an additional resource for infection control and prevention.17 APIC provides publications, resources, textbooks, continuing education, and regular online newsletters upon subscription. These organizations are great resources for ICCs.

Another helpful document is the “ANSI/AAMI ST 79 Comprehensive Guide to Steam Sterilization and Sterility Assurance in Health Care Facilities.”18 It provides comprehensive guidance related to steam sterilizers, regardless of facility and is available for purchase.

Conclusion

Infection control and prevention have changed since the publication of the 2003 CDC guidelines. Adding an ICC to the dental team is key to ensuring safety and compliance in the dental setting. The ICC can help dental offices stay current with changes in infection control and aid in compliance with infection control guidance. Many resources are available to ICCs to help protect the health and safety of patients and staff. Dental offices should consider designating an ICC if they have not already.

References

- United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Summary of Infection Prevention Practices in Dental Settings: Basic Expectations for Safe Care. Available at: cdc.gov/oralhealth/infectioncontrol/pdf/safe-care2.pdf. Accessed December 4, 2022.

- Kohn W, Collins AS, Cleveland JL. Guidelines for infection control in dental health-care settings-2003. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2003;52(RR-17):1–61.

- The Dale Foundation. OSAP-Dale Foundation Dental Infection Prevention and Control Certificate. Available at: dalefoundation.org/courses/catalog/course/osap-dale-foundation-dental-infection-prevention-and-control-certificate-program. Accessed December 4, 2022.

- OSAP/DANB/DALE. Dental Infection Control Education & Certification Available at: dentalinfectioncontrol.org/certification/cdipc.Accessed December 4, 2022.

- American Dental Association Commission on Dental Accreditation. Standard 5-1. Available at: coda.ada.org/-/media/project/ada-organization/ada/coda/files/dent_l_hygiene_standards.pdf?rev=d59cbfa59f094ff48c57d86a4cc15f99&hash=14EE28AA67B4C6589B9E4099CECFDA44. Accessed December 4, 2022.

- Occupational Safety & Health Administration. About OSHA available at: osha.gov/aboutosha#:~:text=OSHA%27s%20Mission,%2C%20outreach%2C%20education%20and%20assistance. Accessed December 4, 2022.

- Occupational Safety and Health Administration. Bloodborne Pathogens Standard. Available at: osha.gov/laws-regs/regulations/standardnumber/딦/딦.1030. Accessed December 4, 2022.

- Occupational Safety and Health Administration. Hazard Communication Standard. Available at: osha.gov/laws-regs/regulations/standardnumber/딦/딦.1200. Accessed December 4, 2022.

- Occupational Health and Safety Administration. Respiratory Protection Standard Available at: osha.gov/laws-regs/regulations/standardnumber/딦/딦.134. Accessed December 4, 2022.

- Occupational Safety and Health Administration. Model Exposure Control Plan. Available at: osha.gov/sites/default/files/CPL_䁰-2_蒑_APPD.pdf. Accessed December 4, 2022.

- Cleveland JL, Bonito AJ, Corley TJ, Foster M, Barker L, Brown GG. Advancing infection control in dental care settings: factors associated with dentists’ implementation of guidelines from the centers for disease control and prevention. J Am Dent. 2012;143:1127–1138.

- Kelsch N, Davis C, Essex G, Laughter L, Rowe D. Effects of mandatory continuing education related to infection control on the infection control practices of dental hygienists. Am J Infect Control. 2017;45:926–928.

- Fluent MT. Infection control in the dental office: compliance revisited. Inside Dentistry. 2013;9(10):1–4.

- Organization for Safety Asepsis and Prevention. The Safest Dental Visit. Available at: osap.org. Accessed December 4, 2022.

- American Dental Hygienists’ Association. Health and Safety Resources. Available at: adha.org/resources. Accessed December 4, 2022.

- American Dental Association. Infection Control & Sterilization. Available at: ada.org/resources/research/science-and-research-institute/oral-health-topics/infection-control-and-sterilization. Accessed December 4, 2022.

- Association for Professionals in Infection Control and Epidemiology. Spreading Knowledge, Preventing Infection. Available at: apic.org/about-apic/about-apic-overview. Accessed December 4, 2022.

- Advancement of Medical Instrumentation (AAMI)/American National Standards Institute (ANSI). ANSI/AAMI ST79 Comprehensive Guide to Steam Sterilization and Sterility Assurance in Health Care Facilities. Available at: aami.org/standards/ansi-aami-st79. Accessed December 4, 2022.

From Dimensions of Dental Hygiene. January 2023; 21(1)22-24,26-27.