Every Moment Counts

All dental team members must be prepared to provide an immediate and coordinated emergency response for patients experiencing chest pain or cardiac arrest in the dental office.

This course was published in the June 2013 issue and expires June 2016. The authors have no commercial conflicts of interest to disclose. This 2 credit hour self-study activity is electronically mediated.

EDUCATIONAL OBJECTIVES

After reading this course, the participant should be able to:

- Identify the necessary components of an emergency kit.

- Describe the symptoms of chest pain and heart attack.

- Discuss how to handle a medical emergency involving a cardiac event in the dental office.

According to the American Heart Association (AHA), 715,000 Americans experience a myocardial infarction each year; 525,000 are first-time cardiac events, while 190,000 have experienced one previously.1 Heart disease remains the leading cause of death for both men and women.1 With the prevalence of heart disease continuing to increase, it is possible that a patient, dental team member, or visitor may experience a cardiac event while in the dental office.

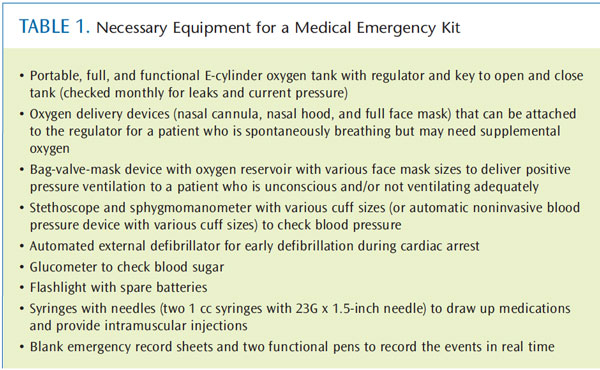

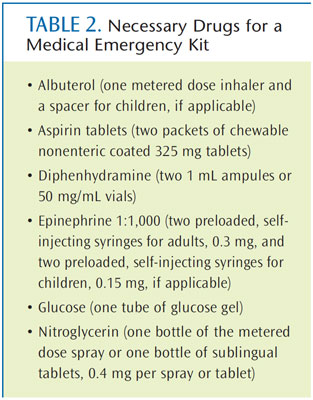

All dental team members need to be prepared to handle a medical emergency. Every office must have an emergency management plan that all team members are well trained in, as well as a fully stocked emergency kit (Table 1 and Table 2). Also, in order to prevent medical emergencies from occurring, every patient should receive a complete medical history review, including recording of vital signs, before dental treatment is initiated. While a myriad of medical emergencies may occur in a dental office, this article will focus exclusively on chest pain and cardiac arrest.

CHEST PAIN

Chest pain is a potential medical emergency seen in the dental office. When patients describe chest pain, they commonly use terms such as “squeezing,” “tightness,” “fullness,” “constriction,” “pressure,” or the feeling of a “heavy weight” on the chest. There are many potential causes of chest pain, such as acute myocardial infarction (AMI), angina pectoris, paroxysmal supraventricular tachycardia, gastroesophageal reflux disease, anxiety, and costochondritis.

Recognizing chest pain is not typically problematic because most patients will alert a dental team member immediately when feeling this sensation. Conscious patients experiencing chest pain should remain in any position that is comfortable; they often want to sit upright. Conscious patients who can talk have a patent airway, are breathing, and have sufficient cerebral blood flow and blood pressure to retain consciousness.

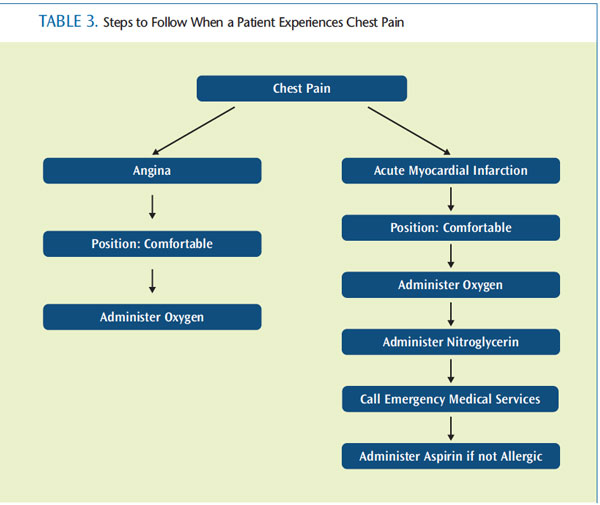

Once a patient has experienced cardiac arrest, he or she is not conscious. Angina pectoris and AMI are the two most common causes of cardiac-related acute pain among conscious patients with chest pain. The challenge for dental team members is providing a differential diagnosis.2

Making a differential diagnosis of chest pain involves evaluating a number of signs and symptoms. Table 3 describes the steps to follow once a cause of the chest pain has been determined. One consideration is the patient’s history. Has he or she ever experienced anginal chest pain? If so, it is likely that the current chest pain is angina pectoris. However, if this is the patient’s first episode of chest pain, dental team members should treat him or her as if it were AMI and have emergency medical services (EMS) transfer the patient as quickly as possible to the hospital.

The quality of pain must also be evaluated to determine a cause. If the pain is significant but not severe, angina pectoris is the most likely culprit, not AMI. Angina pectoris is chest pain or discomfort when the heart is not receiving an adequate supply of blood and oxygen. Pain that radiates, commonly to the left side of the body—the left mandible, left arm, left shoulder—is more often caused by AMI than by angina pectoris. However, not all pain associated with AMI radiates, and some patients have atypical pain during AMI. For example, patients with diabetes and women often experience an unusual shortness of breath and/or an unexplained elevation of blood sugar levels as symptoms of AMI, but no chest pain at all (silent myocardial infarction).3

Blood pressure also might indicate whether the patient is experiencing angina pectoris or AMI. Although exceptions have been reported, if the patient’s blood pressure is elevated during the episode of chest pain, angina pectoris more likely is the cause.4 This elevation may be a response to the pain felt by the patient. If the blood pressure falls below the patient’s baseline value or the immediate preoperative value, dental team members should consider AMI. If the pump (the heart) has been injured, it is less efficient, resulting in a decreased cardiac output and subsequent drop in blood pressure.5

Definitive care for chest pain requires the administration of supplemental oxygen and nitroglycerin, via sublingual tablet or spray. If this resolves the pain, the episode was likely angina pectoris. If the pain is persistent or worse, AMI should be suspected. Immediate activation of EMS, as well as the administration of aspirin, is indicated. Nitrous oxide/ oxygen in a 50:50 concentration may also be administered.6 If the patient loses consciousness, begin chest compressions and basic life support immediately.

CARDIAC ARREST

Witnessing a patient go into cardiac arrest in the dental office is rare, but still possible. In fact, this medical emergency could occur in the parking lot, waiting room, or in the dental chair. Prompt recognition and management that includes early chest compressions, ventilation, immediate access to EMS, and defibrillation, are absolutely critical.7

During cardiac arrest, the heart is unable to adequately pump blood and oxygen to the body. Without proper oxygenation, the patient quickly loses consciousness. Once cardiac arrest is recognized, the dental team must immediately call EMS and retrieve the emergency kit with the portable oxygen tank, bag-valve-mask (BVM), and the automated external defibrillator (AED).

In other medical emergencies, the basic algorithm of emergency management dictates that the patient’s airway, breathing, and circulation be assessed (ABC). In 2010, AHA changed the basic life support guidelines for cardiac arrest from ABC to compressions, airway, and breathing (CAB).8 This change was implemented to prevent any delays in the start of chest compressions. Because patients experiencing cardiac arrest still have oxygen in their lungs and bloodstream, beginning chest compressions immediately can circulate this oxygen to their heart and brain more quickly.9

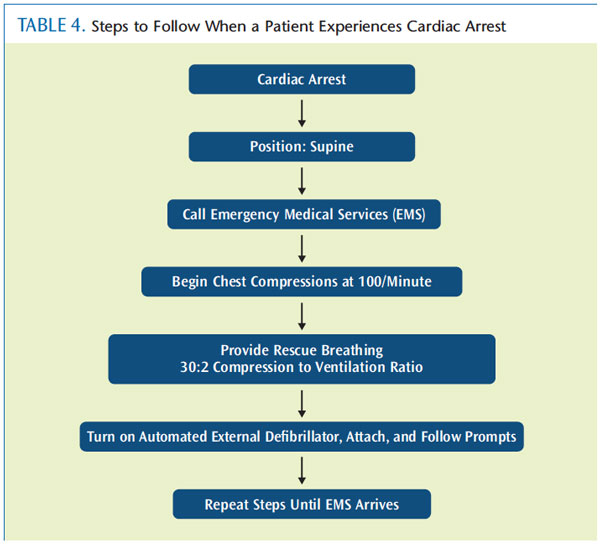

Chest compressions should immediately begin at a rate of 100/minute with a compression depth of at least 2 inches in an adult with good chest recoil. The dental team should attach and use the AED as soon as it is available, minimizing chest compression interruptions. Meanwhile, open the airway with a head-tilt/chin lift (Figure 1), and begin rescue breathing at a compression to ventilation ratio of 30:2. Rescue breathing is most often performed with a BVM device plugged into the portable oxygen tank at 15 L/min. The AHA recommendation for a cardiopulmonary resuscitation cycle of chest compressions is 2 minutes. This is the cycle programmed into the AED once it is turned on. Table 4 includes a flow chart of the necessary steps to follow when a patient experiences cardiac arrest.

SUMMARY

All members of the dental team should receive comprehensive training on basic lifesaving techniques once a year to ensure that all personnel are prepared to perform these duties adequately at any time. Consistent review of the office’s emergency plan, in addition to monitoring the status of the medical emergency kit, can also ensure that dental team members are prepared. Dental professionals are integral to the promotion and maintenance of oral health, and they can also save lives in the face of a life-or-death emergency.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

FIGURE 1 IS REPRINTED WITH PERMISSION FROM: MALAMED SF. MEDICAL EMERGENCIES IN THE DENTAL OFFICE. 6TH ED. ST. LOUIS: MOSBY; 2007.

REFERENCES

- Roger VL, Go AS, Lloyd-Jones DM, et al. Heart disease and stroke statistics—2012 update: a report from the American Heart Association.Circulation. 2012;125:2–220.

- Kreiner M, Okeson JP, Michelis V, LujambioM, Isberg A. Craniofacial pain as the sole symptom of cardiac ischemia: a prospective multicenter study. J Am Dent Assoc. 2007;138:74–79.

- Grundy SM, Howard B, Smith S Jr, Eckel R,Redberg R, Bonow RO. Prevention Conference VI: Diabetes and Cardiovascular Disease—executive summary: conference proceeding forhealthcare professionals from a special writing group of the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2002;105:2231–2239.

- Garfunkel A, Galili D, Findler M, et al. [Chestpains in the dental environment]. Refuat Hapeh Vehashinayim. 2002;19:51–59,101.

- Malamed SF. Sedation: A Guide to PatientManagement. 5th ed. St. Louis: Mosby; 2010:475.

- Homayounfar SH, Broomandi SH. Evaluationof Entonox as an analgesic for relief of pain in patients with acute myocardial infarction. Iran Heart J. 2006;7:16–19.

- Phero JC. Basic life support is critical to successful cardiopulmonary resuscitation. Inside Dentistry. 2011;3:122–123.

- Berg RA, Hemphill R, Abella BS, et al. Part 5:adult basic life support: 2010 American Heart Association Guidelines for Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation and Emergency CardiovascularCare. Circulation. 2010;122(Suppl):685–705.

- Cave DM, Gazmuri RJ, Otto CW, et al. Part 7:CPR techniques and devices: 2010 American Heart Association Guidelines for Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation and EmergencyCardiovascular Care. Circulation. 2010;122(Suppl):S720–S728.

From Dimensions of Dental Hygiene. June 2013; 11(6): 56–59.