Demystifying Occlusion

Demystifying occlusion dental hygienists can help their patients prevent significant occlusal problems with education and assessment.

This course was published in the June 2013 issue and expires June 2016. The author has no commercial conflicts of interest to disclose. This 2 credit hour self-study activity is electronically mediated.

EDUCATIONAL OBJECTIVES

After reading this course, the participant should be able to:

- Identify different types of occlusal problems.

- Discuss treatment options for occlusion problems

- Describe how to assess for a variety of potential occlusal problems.

Occlusion can seem like a complex and confusing subject. Temporomandibular disorders (TMDs), centric relation, maximum intercuspation, working and nonworking interferences, canine guidance, disk displacement, and parafunctional habits all affect the dentition, and related disturbances can interfere with patients’ masticatory systems. Dental hygienists should have an understanding of tooth movement so they can effectively advise their patients, who often seek out their expertise about matters regarding both oral and systemic health. The masticatory system is composed of the structures required for adequate chewing, including the jaw and its related muscles, teeth, temporomandibular joints, tongue, lips, cheeks, and mucous membranes (Figure 1). The teeth are just one part of the masticatory system, and if they are not in total equilibrium with the rest of the masticatory system, problems are likely to occur.1

Dental hygienists have the opportunity to intercept failures in this masticatory system by observing certain signs and symptoms during routine dental hygiene appointments. With a basic understanding of relevant concepts and principles, dental hygienists can alert the patient and dentist to possible problems.

TEMPOROMANDIBULAR DISORDERS

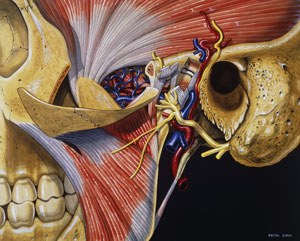

TMDs affect the masticatory muscles and the temporomandibular joint (TMJ), resulting in pain and/or dysfunction.2 TMJ and TMD are often used interchangeably when, in fact, TMD refers to the dysfunction and TMJ refers to the anatomical structure of the joint (Figure 2).

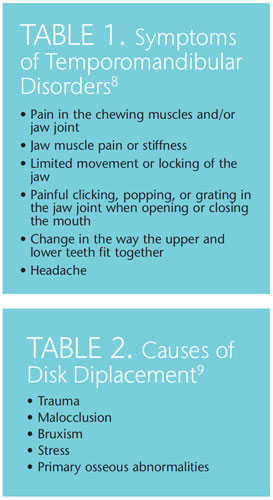

TMDs are the most common causes of nontooth-related chronic orofacial pain, with a prevalence between 5% and 12%.3–7 TMDs are more common among young people, particularly women.4–7 Risk is increased among women who take an estrogen supplement or use oral contraceptives.4–7 Table 1 (page 64) provides a list of symptoms.8

CENTRIC RELATION

Centric relation (CR) is defined as “the relationship of the mandible to the maxilla when the properly aligned condyle-disk assemblies are in the most superior position against the eminentiae irrespective of vertical dimension or tooth position.”1 In other words, CR is the position of the mandible in relation to the maxilla when everything is in the correct physiologic position. Tooth position and occlusion do not determine CR as it is strictly a joint position.

MAXIMUM INTERCUSPATION

Formerly known as centric occlusion, maximum intercuspation (MI) occurs when the maxillary and mandibular teeth are fully interposed, ie, the position of maximum closure of the mouth (Figure 3). Often the terms CR and MI are used interchangeably, when in reality they are very different. While CR is an optimal joint position, MI refers to a relationship between teeth. In order to gain occlusal harmony, the aim is to make MI coincide with CR, so that when the teeth are fully interposed, the condyles are properly seated in the joint space with the disk properly in place.

WORKING AND NONWORKING INTERFERENCES

When CR and MI do not coincide, working and nonworking interferences can occur that cause the mandible to deviate from its normal physiologic position. A working interference occurs when the teeth contact prematurely on the side where the active chewing or biting is taking place. In other words, if the teeth are brought together and the mandible shifts to one side, the working interference will be on the side of the mouth that the mandible is sliding toward. A nonworking interference occurs on the opposite side from where the mandible is sliding.

CANINE GUIDANCE

Canine guidance, or canine protected occlusion, refers to the disocclusion by the canines of all other teeth when the jaw is moved from side to side.1 When the posterior teeth are in contact, the heavy muscles of mastication are triggered to fire, greatly increasing the occlusal load, or biting forces. By only contacting on the canines during lateral movements, the heavy muscles of mastication stay relaxed, and occlusal forces are dramatically decreased. If working or nonworking interferences occur during these movements, abnormal wear patterns can result. These areas of wear, or wear facets, can be seen by the dental hygienist during recare appointments. Wear facets appear as flat, shiny areas of tooth structure where the normal occlusal anatomy has been worn away. Dental hygienists can point out these areas to patients and explain their etiology, which will assist patients in making an informed decision about corrective treatment.

DISK DISPLACEMENT

Disk displacement or internal derangement is when the articular disk is out of position. There are many different types of displacement and various causes (Table 2) of these derangements, which make diagnosis and treatment challenging.9 Advances in imaging with conebeam computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging have helped to make diagnosis more accurate.1

PARAFUNCTIONAL HABITS

Nonfunctional mandibular movements, such as bruxism, nail biting, finger/thumb sucking, speech alteration, mouth breathing, pacifier use, prolonged gum chewing, and atypical swallowing, are associated with a variety of jaw muscle symptoms and disk derangements.10 Chronic parafunctional clenching is suspected in chronic and acute TMDs. These habits are typically more common among women than men, and may often increase in frequency and intensity when patients experience stress.11

ASSESSMENT

Treatments for TMD or occlusion related problems can range from a “watch and wait” approach, to minor occlusal adjustments, to fabricating occlusal guards. Dental hygienists can help patients understand that something is out of balance with the masticatory system and that if left untreated, problems may occur. Evidence of these types of failures easily noticed during routine dental appointments may include worn or fractured teeth, fractured restorations, and sore and/or enlarged muscles of mastication.

Aspects of occlusal evaluation are simple to evaluate during recare appointments. Maximum opening is a good indicator of potential TMJ issues. Normal maximum opening is typically 40 mm to 50 mm, or about the width of four fingers. Most people can move their jaw to each side about 7 mm to 15 mm and can protrude their jaw 10 mm to 15 mm.1 If a patient has limited opening, there may be something out of balance with the masticatory system. Palpating the muscles of mastication during routine oral cancer screening is a simple strategy to check for masticatory system problems. Palpating the temporal, occipital, masseter, sternocleidomastoid, digastrics, trapezius, and pterygoid muscles and noting tenderness can indicate occlusal disharmonies. Again, educating the patient about the possible link between tenderness of these muscles and occlusal issues will encourage them to seek further diagnosis.

Special attention should be given to the occlusal assessment of teeth restored with dental implants. In mouths that have a combination of both natural teeth and dental implants, care should be taken to ensure that the dental implants are not overloaded. Teeth are supported and attached to the alveolar bone by the periodontal ligament. This soft tissue attachment to the hard, boney surface allows for a small amount of tooth movement. Movement up to 50μm in any direction is considered normal in a healthy periodontium. Dental implants, on the other hand, have no soft tissue interface and are integrated directly with the alveolar bone. No movement with crowns supported by dental implants is considered normal. This difference in the dynamic interface of teeth and implants to alveolar bone means that the occlusal load will vary. In a mouth that has all natural teeth, the occlusal contacts should be spread evenly, both in spacing and force, along all of the posterior teeth when the patient taps his or her teeth together straight up and down. Anterior teeth may or may not come in contact during this type of movement. If the patient has canine-protected occlusion, there should be no contact of posterior teeth during excursive or grinding movements.

This assessment can be accomplished by using articulating paper and having the patient first bite lightly, straight up-and-down. After marking the teeth during this movement, the dental professional should observe even-sized marks on the natural teeth and no marks on the crowns supported by implants. Next, have the patient strongly clench and grind his or her teeth side-to-side while the articulating paper is interposed. This time, the marks on the implant crowns located in the central grooves of the occlusal tables of posterior teeth and on the tips of the functional cusps should be noted. There should be no marks on cuspal inclines of any posterior teeth. If the dental hygienist notices any inappropriate marks, the dentist should be notified so appropriate occlusal adjustments can be made.12

During excursive movements, there should be no contact along cuspal inclines of crowns supported by dental implants. When the patient clenches tightly and grinds side to side, the periodontal ligament is compressed and the tooth actually depresses slightly in the socket. This is the reason for the lighter occlusal pattern that should be placed on dental implant crowns.

Because occlusal patterns and loads on natural teeth can vary over time as they shift and move, possibly affecting the placement of implants, patients with a combination of natural teeth and dental implants should have their occlusion periodically examined. The hygiene recare appointment is the perfect opportunity for this reevaluation.

CONCLUSION

A few simple checks and patient education can avert many problems associated with occlusal issues. By noting these types of occlusal problems early and encouraging patients to address them and comply with treatment, dental hygienists can help patients avoid costly rehabilitation in the future.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

FIGURE 1. ANATOMICAL TRAVELOGUE/SCIENCE SOURCE

FIGURE 2. PETER CULL/SCIENCE SOURCE

REFERENCES

- Dawson PE. Functional Occlusion: From TMJ to Smile Design. Philadelphia: Mosby;2006:6,59,229, 271.

- Goldstein BH. Temporomandibular disorders: a review of current understanding. Oral Surg OralMed Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 1999;88:379–385.

- McNeil C. Management of temporomandibular disorders: concepts and controversies. J Prosthet Dent. 1997;77:510–522.

- Johansson A, Unell L, Carlsson GE, Söderfeldt B, Halling A. Gender difference in symptoms related to temporomandibular disorders in a population of 50-year-old subjects. J Orofac Pain.2003;17:29–35.

- Macfarlane TV, Blinkhorn AS, Davies RM, Kincey J, Worthington HV. Oro-facial pain in the community: prevalence and associated impact. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2002;30:52–60.

- Pow EH, Leung KC, McMillan AS. Prevalence of symptoms associated with temporomandibular disorders in Hong Kong Chinese. J Orofac Pain. 2002;15:228–234.

- Goulet JP, Lavigne GJ, Lund JP. Jaw pain prevalence among French-speaking Canadians in Quebec and related symptoms of temporomandibular disorders. J Dent Res. 1995;74:1738–1744.

- National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research. Temporomandibular Joint and MuscleDisorders. Available at: www.nidcr.nih.gov/OralHealth/Topics/TMJ/. Accessed May 15, 2013.

- Berquist T. MRI of the Musculoskeletal System. 4th ed. Baltimore: Lippincott Williams &Wilkins, 2000.

- Castelo PM, Gavião MB, Pereira LJ, Bonjardim LR. Relationship between oral parafunctional/nutritive sucking habits and temporomandibular joint dysfunction in primary dentition. Int J Paediatr Dent. 2005;15:29–36.

- Bhat S. The etiology of temporomandibular disorders: the journey so far. InternationalDentistry. 2010;4:88–92.

- Misch CE. Contemporary Implant Dentistry. 2nd ed. St. Louis: Mosby Inc; 1999:151–162.

From Dimensions of Dental Hygiene. June 2013; 11(6): 60, 63–65.