PEOPLEIMAGES/E+/GETTY IMAGES PLUS

PEOPLEIMAGES/E+/GETTY IMAGES PLUS

Ensure Career Longevity With Eye Health

As dental hygienists rely on their visual acuity to effectively treat patients, promoting eye health is important.

In order to ensure career longevity and provide the best possible care to patients, dental hygienists must take care of their bodies. Preventing musculoskeletal disorders as well as eye problems is key to a healthy career. Visual acuity, or the sharpness of vision at a distance, is paramount to successful clinical care. Normal visual acuity is defined as 20/20 vision, or the ability to see clearly at 20 feet.1 An individual with decreased visual acuity may have 20/100 vision, meaning he or she needs to be 20 feet away to see what someone with normal visual acuity can see at 100 feet.1

Visual acuity tends to diminish naturally with age; however, certain conditions inherent to the dental hygiene profession—including a small visual field, dim lighting, and use of computer screens—tend to worsen visual acuity more quickly.2 Oral health professionals should know the definition of visual acuity, understand strategies to treat ocular disorders and conditions, and identify how visual acuity may impact their careers.

The Eye As a Complex Organ

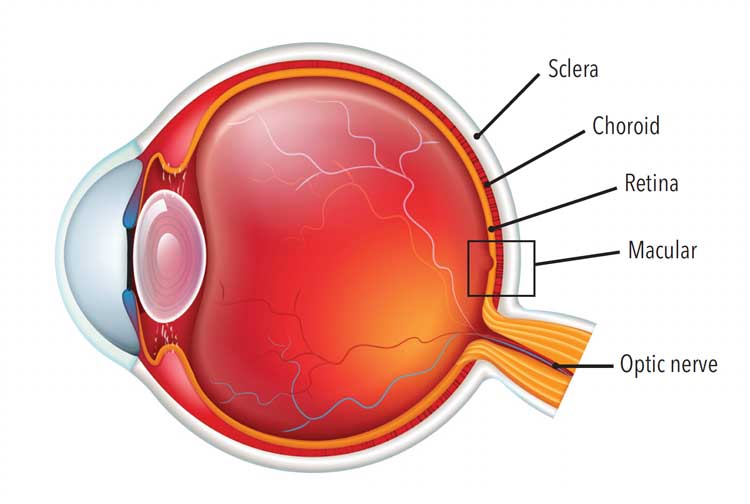

A complex organ, the human eye is part of the sensory nervous system, and is composed of an anterior and posterior section.3 The anterior section includes the cornea, iris, and lens, while the posterior section houses the vitreous, retina, choroid, and sclera (Figure 1). The cornea is the clear front area that transmits and focuses light into the eye. The iris determines eye color and houses the pupil. The pupil will change in size depending on how much light enters the eye. The lens is the transparent part of the anterior section that focuses light wavelengths onto the retina.3

To give the eye its shape, a gel-like substance called vitreous fills up the entire center of the eyeball. Moving posteriorly, the retina is the nerve layer that lines the back of the eyeball. The retina helps pass sensory messages into the optic nerve for the brain to receive. The choroid is located between the retina and the sclera. Found in the back of the eye, this area houses the eye’s necessary blood vessels. Finally, the sclera is the white outercoat of the eye.3

All parts of this complex organ work together to make the human eye function like a camera. Light rays pass through the cornea to the lens, and these two parts focus the wavelengths on the retina, which in turn, sends electromagnetic impulses along the optic nerve to the brain. All of these actions happen in seconds and result in sight.3

Age-Related Ocular Changes

The natural process of age-related changes to the ocular lens is called presbyopia. This process typically begins around age 40, and it inhibits individuals’ ability to see objects at the same distances that they once did. Presbyopia is the hallmark for recognizing the need for glasses. Before getting corrective lenses, an individual may start holding objects closer or farther away to compensate for the decline in vision.2

The pupil also undergoes age-related changes. When the pupil shrinks, light is not seen as vividly as before. The average older adult requires three times more ambient light for his or her pupil to work as efficiently as a person in his or her 20s. Aging may also cause peripheral vision to diminish because the size of the field of vision decreases by 1° to 3° per decade after age 50.2

In addition to the changes to the shape of the eye, mature eyeballs lose cells that detect color. As a result, colors will not appear as vibrantly as they once did, and differentiating between similar colors may be difficult. The human eye also loses vitreous gel around the retina over time, which may cause the retina to detach if vitreous gel is lost too quickly. Furthermore, middle-aged or older individuals, especially women, are at an increased risk for dry eyes due to hormonal changes and the ocular region producing fewer tears with age.2

Changes in color detection and the need for more ambient light are concerns for dental hygienists because of how frequently both are used when working in the oral cavity. Ample light is needed to see fine detail and the posterior region of the mouth. Color contrast is used when detecting numerous oral health problems such as oral pathology and severity of gingivitis and periodontal diseases.

Impact of Dental Equipment on Visual Acuity

Oral health professionals are at increased risk for eye injury and a decline in visual acuity if proper protection is not used. The production of aerosols from ultrasonic scalers, air polishers, and air-driven handpieces can damage the eye if proper personal protection equipment is not worn.4,5 In addition, dental hygienists’ small field of view over an average workday causes the eyes to remain focused for long periods of time, reducing lubrication.6 Certain dental procedures, such as placing sealants and providing laser therapy, use devices that emit strong wavelengths of light that may injure unprotected eyes. Dental curing lights emit a blue light with short wavelengths, which can induce corneal damage, resulting in ocular inflammation and dry eyes.4,5,7 When operating dental curing lights, dental hygienists should don appropriate protective eyewear and eye shields with orange filters to cover the light-curing devices.4,5,8 Although the use of special ocular glasses and shields are best to block out the light, the operator should still turn away to avoid staring directly at the curing light.

The use of coaxial illumination provides more intensity than traditional overhead lights. This increased intensity and alignment with the clinician’s field of vision improve vision and posture. Implementing loupes with coaxial illumination also provides ergonomic benefits.9

Oral health professionals should also take necessary actions to protect their eyes when performing laser therapy. Currently, 16 states allow the use of lasers during dental hygiene treatment.10 With an increasing number of dental hygienists implementing this technique, the recommended safety precautions must be followed to prevent eye injury. Anyone within the “nominal hazard zone,” which is defined as the area within the direct, reflected, or scattered radiation of the laser beam, must wear appropriate laser safety eyewear.11,12 The appropriate eyewear is specific to laser manufacturers and depends on hazard class.11 Specialized eyewear is important with laser therapy because of the concentration of power densities the laser emits, which are “high enough to evaporate tissue, metal, or ceramics,” including ocular nerves and tissue.4,5,12 If proper eye protection recommendations for dental curing lights and lasers are not followed, visual acuity could be seriously jeopardized.

Effects of Digital Technology on Visual Acuity

Digital technology is becoming more prominent in the dental field. As such, the eyes of oral health professionals are at heightened risk for computer vision syndrome or digital eye strain. Research shows that extended viewing of a computer screen during the workday may be harmful to eye health.13 Approximately 30% of the light emitted from computers is blue light, or high-energy visible, and almost all of it goes through the cornea and lens, reaching the retina.13 Blue light is found in various sources, including sunlight, fluorescent and light-emitting diode lighting, televisions, computers, smartphones, and other digital devices.13,14

Although digital technology emits only a small fraction of blue light, the amount of time oral health professionals spend using computer screens is concerning.13 Constant viewing of a screen reduces blinking. For dental hygienists viewing computer screens to review medical and dental histories, note dental charting findings, record periodontal assessment findings, expose and review digital radiographs and photos, go over chart notes, and write treatment notes, this repeated exposure to blue light may cause dry eye syndrome and computer vision syndrome.6,15

Computer vision syndrome may lead to other symptoms such as eye strain, headaches, blurred vision, dry eyes, and neck, back and shoulder pain. These symptoms may be caused by the glare on the computer screen, poor lighting, or improper viewing distance.15 The American Academy of Ophthalmology (AAO) states that the blue light emitted from computer screens has not been proven to harm eyes; however, staring at a computer screen for an extended time can cause computer vision syndrome.16

Maintaining Visual Acuity

To protect and maintain visual acuity, all oral health professionals should schedule regular, comprehensive eye examinations. These exams are important preventive measures because many ocular problems do not present with signs or symptoms.6 Dental hygienists should share their typical workday conditions with their optometrists. Dental professionals staring at various screens throughout the workday will want to notify their vision specialist so they can accurately monitor their visual acuity. During an ocular exam, glaucoma, macular degeneration, cataracts, dry eyes, hypertension, and diabetes may be detected.6 Oral health professionals should follow the AAO’s 20/20/20 rule, which suggests individuals look at an item 20 feet away for 20 seconds every 20 minutes.6,14–16

Dental hygienists often struggle to maintain proper ergonomics while working in the oral cavity, and poor ergonomics can lead to ocular deterioration. Clinicians should sit an arm’s length from the computer screen, reduce the glare and brightness of the screen, and wear eyeglasses instead of contacts, as contacts may increase dryness and irritation.16 Computer screens should be about 4 inches or 5 inches below eye level to help reduce the symptoms of computer vision syndrome; however, this is not always possible.15 For example, when completing periodontal charting, the dental hygienist may be looking up at the screen and then back into the mouth. Additional eye strain may occur as the clinician looks at a computer screen or tablet and then back into a small field of view when focusing on the oral cavity.

While working in the oral cavity, clinicians typically are a short distance—27 cm to 50 cm— from the eye to the working area. Most workplace screens are kept at an intermediate distance, 40 cm to 90 cm from the eye to the working area.17 Going from a short distance to an intermediate distance frequently causes the ocular muscles to tighten.18 This tightening is often confused with other symptoms such as fatigue, eye pain, ocular irritation, blurred vision, and headaches.18

When dental hygienists are using equipment with special wavelength frequencies, they need to ensure that proper protection is worn to protect their visual acuity. Finally, all oral health professionals should remember their visual acuity can be impacted by personal screen time use; therefore, limiting digital use outside of the office can also help support eye health.13 Other strategies to support visual acuity during leisure time include the use of sunglasses and glasses with anti-reflective coatings and blue filters.6,15 Blue light glasses can help reduce the amount of blue light that enters the eye by filtering it out.13,14,16 While research demonstrating a causal link between computer-based blue light and eye damage is not available, dental hygienists should maintain their visual acuity when working with computers, especially when they often alternate views from the oral cavity to their computer screens.

Magnification

The use of loupes helps dental hygienists improve their working posture and reduce pain.19–22 Additionally, as vision declines, wearing loupes is key to maintaining the sight necessary to perform precise tasks in a small space.9,23 Clarity and sharpness of vision are integral to effective dental hygiene practice, and loupes support clinicians in achieving these goals. Further benefits of magnification in dental hygiene practice include enhanced ability to see during scaling and root planing, improved indirect vision, and better vision regardless of age.9

Conclusion

Dental hygienists must strive to maintain their visual acuity in order to enjoy a long and successful career. Damage to the ocular region may compromise patient care. Visual acuity is unique to each clinician and thus will need to be addressed on a personal level. As the use of digital technology is increasing in the dental hygiene profession, clinicians should maintain their visual acuity by scheduling comprehensive eye examinations on a routine basis. After an honest assessment based on personal and professional screen time usage, a tailored recommendation of treatment can be made. In the future, more research should be conducted analyzing the extent of digital exposure experienced by oral health professionals during a workday.

References

- American Optometric Association. Visual Acuity: What Is 20/20 Vision? Available at: aoa.org/patients-and-public/eye-and-vision-problems/glossary-of-eye-and-vision-conditions/visual-acuity. Accessed September 22, 2021.

- Heiting G. How vision changes as you age. Available at: allaboutvision.com/over60/vision-changes.htm. Accessed September 22, 2021.

- Kellogg Eye Center. Anatomy of the Eye. Available at: umkelloggeye.org/conditions-treatments/anatomy-eye. Accessed September 22, 2021.

- Brinker S. The career-ending injury no one talks about. Available at: dentalproductsreport.com/dental/article/career-ending-injury-no-one-talks-about. Accessed September 22, 2021.

- Ekmekcioglu H, Unur M. Eye-related trauma and infection in dentistry. J Instanb Univ Fact Dent. 2017;5:55–63.

- Goffron-Mercieri J. Focusing on our vision. Available at: dentistryiq.com/dental-hygiene/student-hygiene/article/14035375/eyecare-protection-for-dental-hygienists. Accessed September 22, 2021.

- Alasiri R, Algarni H, Alasiri R. Ocular hazards of curing light units used in dental practice—a systematic view. Saudi Dent J. 2019;31:173–180.

- Stamatacos C, Harrison J. The possible ocular hazards of LED dental illumination applications. J Tenn Dent Assoc. 2013;93:26–30.

- Arnett MC, Eagle I. Impact of loupes and lights on visual acuity and ergonomics. Dimensions of Dental Hygiene. 2021;19(8):21–23.

- Academy of Laser Dentistry. States That Allow Laser Use by Dental Hygienists. Available at: laserdentistry.org/uploads/files/Reg%20Affairs/Regulatory%20Chart%20YES%204_2018%20-%20YES.pdf. Accessed September 2, 2021.

- LeBeau J. Laser safety in the dental office. Available at: laserdentistry.org/uploads/files/misc/Laser%20Safety%20in%20the%20Dental%20Office_012216.pdf. Accessed September 2, 2021.

- Laservision. Guide to Laser Safety. Available at: lasersafety.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/08/LaserSafetyGuide.pdf. Accessed September 2, 2021.

- Heiting G. Blue light: It’s both bad and good for you. Available at: allaboutvision.com/cvs/blue-light.htm. Accessed September 2, 2021.

- Ellis R. Blue light glasses—helpful or just hype? Available at: webmd.com/eye-health/news/20191216/do-blue-light-glasses-work. Accessed September 2, 2021.

- American Optometric Association. Computer Vision Syndrome. Available at: aoa.org/patients-and-public/caring-for-your-vision/protecting-your-vision/computer-vision-syndrome. Accessed September 21, 2021.

- Porter D. Blue light and digital eye strain. Available at: aao.org/eye-health/tips-prevention/blue-light-digital-eye-strain. Accessed September 21, 2021.

- Marsh L, Rivera M. Improving visual acuity. Dimensions of Dental Hygiene. 2019;17(6):21–24.

- Bedinghaus T. Computer vision symptoms and treatment. Available at: verywellhealth.com/computer-vision-symptoms-3422093. Accessed September 21, 2021.

- Branson BG, Bray KK, Gradbury-Amyot C, et al. Effect of magnification lenses on student operator posture. J Dent Educ. 2004;68:384–389.

- Maillet JP, Millar AM, Burke JM, Maillet WA, Neish NR. Effect of magnification loupes on dental hygiene student posture. J Dent Educ. 2008;72:33–44.

- Hayes MJ, Osmotherly PG, Taylor JA, Smith DR, Ho A. The effect of loupes on neck pain and disability among dental hygienists. Work. 2016;53:755–762.

- Hayes M, Osmotherly P, Taylor J, Smith D, Ho A. The effect of wearing loupes on upper extremity musculoskeletal disorders among dental hyginists. Int J Dent Hyg. 2014;12:174–179.

- Perrin P, Ramseyer ST, Eichenberger M, Lussi A. Visual acuity of dentists in their respective clinical conditions. Clin Oral Investig. 2014;18:2055–2058.

From Dimensions of Dental Hygiene. October 2021;19(10)14,16-18.