Emergency Response

Oral health professionals and office staff members should be prepared to handle an urgent medical situation in the dental office.

Medical emergencies, while uncommon in the dental office, necessitate a well-coordinated and immediate response from oral health professionals and office staff members alike. Dental offices should be prepared to address all types of medical emergencies—ranging from minor incidents to life-threatening situations. Preparedness includes ensuring that each dental team member is effectively trained to respond appropriately to emergencies, staging office-wide drills that replicate emergency situations, and maintaining an emergency kit in the dental office that is accessible at all times.

PREVALENCE OF MEDICAL EMERGENCIES IN THE DENTAL SETTING

While medical emergencies do not occur frequently in the dental office, the increasing numbers of older adults and patients with disabilities who receive treatment in the private dental practice setting may increase the likelihood of an emergency medical situation happening during the provision of oral health care.1 Anders et al,1 who looked at the number of emergency medical events that occurred at the University at Buffalo School of Dental Medicine in NY over 8.5 years, found the prevalence of such events to be low. They found that 164 medical emergencies occurred per 1 million patient visits.1 The most commonly reported events were cardiovascular problems, syncope (fainting), complications related to local anesthesia, and hypoglycemia.1

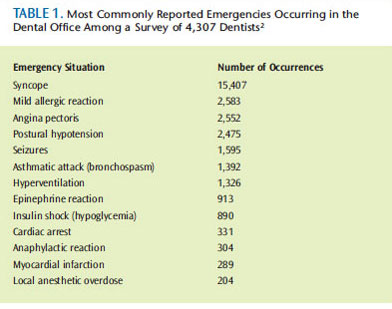

On the other hand, in a survey of 4,307 dentists located across North America, respondents reported experiencing a combined total of more than 30,000 emergencies throughout their years in private practice.2 Syncope accounted for 50.3% of the reported emergency events (Table 1 provides a list of the most commonly reported emergencies from this survey).2 The dental team’s failure to recognize and/or address patient’s dental phobias and the absence of effective pain control were the precipitating causes of more than 75% of all the emergencies experienced by the surveyed dentists.2 Other emergencies that are likely to occur include common medical problems that become exacerbated during the patient’s time in the dental office, such as angina, seizures, asthmatic attack (bronchospasm), and seizures. Hyperventilation and adverse reactions to epinephrine are two common events caused by patients’ fear of dental treatment.

PREPARING FOR A MEDICAL EMERGENCY

The most common mistake dental personnel make when handling medical emergencies is panicking. It is challenging to respond to unexpected, potentially life-threatening situations. Panic is caused by the infrequency of medical emergencies occurring in the dental office and a lack of preparedness for these situations. This is why it is imperative for all dental personnel to be adequately trained and prepared.3

In order for oral health professionals to feel confident in their abilities to handle an emergency, all team members, including front office personnel, should take a basic life support class designed for health care providers. This program should be provided on an annual basis in the dental office, where it will be more realistic and most impactful.4 The American Heart Association (heart.org) and the American Red Cross (redcross.org) are good resources for basic life support training.

Developing an emergency management plan is also essential. A predetermined flow chart that lists the appropriate steps to take in the face of a medical emergency should be created, disseminated to all team members, and regularly updated. In addition, when the dental office team meets for its morning huddle or weekly staff meetings, specific patients’ medical conditions should be discussed, as well as plans to handle such situations in the event they become emergencies.

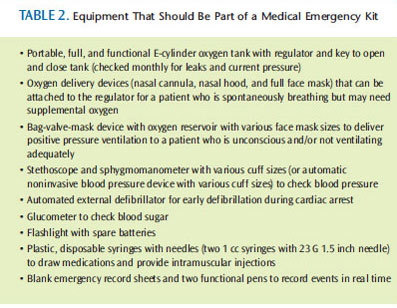

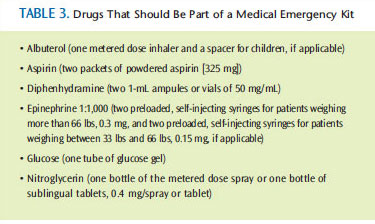

An up-to-date emergency kit should be maintained in every dental office. All dental team members need to know where it is kept, and one staff member should be in charge of restocking it and ensuring that the included medications are not expired. Table 2 and Table 3 provide a list of the equipment and drugs that comprise a well-stocked emergency kit.5 A bare-bones kit should contain the following drugs and equipment: epinephrine (in an auto injector syringe); injectable diphenhydramine; powdered aspirin; nitroglycerin; sugar; a bronchodilator inhaler; oxygen; automated external defibrillator; plastic, disposable syringes for drug administration; and face masks for the delivery of oxygen.

LIABILITY OF INDIVIDUAL PRACTITIONERS

Dental hygienists can, and will be held liable when a medical emergency occurs and the patient’s condition is improperly recognized and inadequately managed. The dentist will also be held liable, but all other members of the dental office staff—including dental hygienists, dental assistants, and possibly even front-office personnel—can be included in the legal or dental board regulatory action that may follow an emergency incident. This is one of the reasons that dental hygienists need to maintain individual malpractice insurance so they will be protected in these types of situations.

CONCLUSION

Preparedness is the key to effectively handling emergencies in the dental office. All members of the dental office team should feel confident in their ability to provide basic lifesaving measures and well versed in the office’s emergency management plan. Many resources are available, including continuing education courses, textbooks, literature articles, and proprietary kits, to help dental practices ensure they are ready to handle any type of medical emergency.

REFERENCES

- Anders PL, Comeau RL, Hatton M, Neiders ME. The nature and frequency of medical emergencies among patients in a dental school setting. J Dent Educ. 2010;74:392–396.

- Malamed SF. Managing medical emergencies. J Amer Dent Assoc. 1993;124:40–53.

- Haas DA. Preparing dental office staff members for emergencies: developing a basic action plan. J Am Dent Assoc. 2010;141(Suppl):85–135.

- Malamed SF. Medical Emergencies in the Dental Office. 6th ed. St. Louis: Mosby; 2007.

- Fonner AM, Reed KL. Be prepared. Dimensions of Dental Hygiene. 2013;11(5):50–51.

From Dimensions of Dental Hygiene. January 2014;12(1):39–41.