MONKEYBUSINESSIMAGES/ISTOCK/GETTY IMAGES PLUS

MONKEYBUSINESSIMAGES/ISTOCK/GETTY IMAGES PLUS

Disclosing Infectious Disease Status

Although the risk of transmission is low in dental settings, oral health professionals should be knowledgeable of any regulations requiring disclosure of an infectious disease.

This course was published in the March 2021 issue and expires March 2024. The authors have no commercial conflicts of interest to disclose. This 2 credit hour self-study activity is electronically mediated.

EDUCATIONAL OBJECTIVES

After reading this course, the participant should be able to:

- Describe infectious disease transmission from providers to patients in the dental setting, and measures that will minimize risk from bloodborne pathogens.

- Explain the risk of transmission posed by various bloodborne pathogens, and factors that affect transmission between clinicians and patients.

- Discuss recommendations for disclosing a clinician’s infectious disease status to an expert review panel, as well as patients.

Transmission of hepatitis B virus (HBV) and human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) from oral healthcare providers to patients in the 1970s and 1980s increased awareness of disease transmission risks in healthcare settings.1 Realization that bloodborne pathogens (BBPs) could be transmitted while conducting an exposure-prone procedure resulted in the United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) guidelines for the continued practice of HBV-positive and/or HIV-positive dental professionals.1 The CDC characterizes an exposure-prone procedure as any that poses a risk of percutaneous injury to providers due to limited visibility or confinement within an anatomical site.1 Not counting the recent appearance of COVID-19, HBV, hepatitis C virus (HCV), and HIV pose the greatest potential for disease transmission in healthcare settings.2 Disclosure of a provider’s infectious disease status to patients is highly controversial. This article reviews infectious disease transmission in dentistry, and explains CDC recommendations and state regulations regarding infectious disease disclosure by HBV-positive or HIV-positive providers.

According to the CDC, three conditions must be present for a provider to pose a risk of BBP transmission to patients: (1) the clinician must have a virus circulating in his or her bloodstream; (2) there must be an injury or condition (eg, weeping dermatitis) present to allow direct exposure of infectious bodily fluids; and (3) there must be a port of entry, such as a wound or mucous membrane, for viral transmission to occur.3,4

HEPATITIS B

HBV can present as an acute infection, lasting for a few weeks, or can become a chronic, lifelong illness. HBV is passed through contact with infected blood or other infected bodily fluids, and is transmissible through a percutaneous injury (such as a needlestick).3–6 The risk of transmission of HBV due to exposure involving infected bodily fluids ranges from 6% to 37%.2 The range of infectivity varies due to the presence or absence of the HBV e-antigen (HBeAg).3 The risk of transmission from a percutaneous exposure involving an HBeAg-positive individual ranges from 19% to 37% if not vaccinated.1,7 A review of HBV transmission from healthcare providers to patients found 77% of the cases resulted from a provider who was HBeAg-positive.6 Guidelines from the CDC recommend HBV DNA serum levels be used to determine infectivity because they serve as a better indicator than HBeAg status alone.4

In order to prevent transmission of BBPs, clinicians are advised to follow CDC standard precautions, which include vaccination, infection control protocols, use of safety device (eg, puncture-resistant sharps containers and needle-retracting devices), and implementing safe work practices.1,3,4 As a result of this guidance, the CDC estimates the incidence of HBV infections have fallen fivefold between 1980 and 2010, from 208,000 to 38,000 incidents per year.6

HEPATITIS C

Similar to HBV, HCV is an infection of the liver that can cause cirrhosis and liver cancer. This virus is transmitted through contact with infected blood, typically through sharing needles and other drug injection equipment.8 Unlike HBV, there is no vaccine for HCV.8 According to the CDC, there is a low risk of transmission of HCV through occupational exposure to blood;3 rather, the majority of healthcare-associated transmissions are attributed to inadequate infection control practices during patient care and hemodialysis.8 The risk of transmission associated with percutaneous exposure to an HCV-positive individual is approximately one in 30.2,3 There have been no documented cases of HCV transmission from provider to patient in the dental field.2,3,7

HUMAN IMMUNODEFICIENCY VIRUS

This virus attacks the immune system and can progress to acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS).9 Once infected, HIV attacks the host’s CD4 (T cells) and incorporates itself into the host’s DNA.9 New virus invasions can be stopped with antiretroviral medications, but the viral DNA cannot be eliminated from the host’s DNA once it is incorporated.9

One of the most important variables that impact the rate of HIV transmission is the exposure site. The risk of HIV transmission is approximately one in 300 (0.3%) following a single percutaneous exposure.2,10,11 However, the risk of transmission drops to 0.1% if the exposure involves a mucous membrane, such as the oral cavity.1,12 The risk of HIV transmission associated with blood contacting the skin remains unknown, but the CDC suggests it is less than 0.1%.3,11 According to a case-control study of HIV seroconversion following a percutaneous exposure, three factors increase the risk of HIV transmission: (1) a deep injury; (2) injury with a device visibly contaminated with blood; and (3) procedures involving a needle placed directly into an artery or vein.11 This study also concluded there is a higher risk of HIV transmission associated with exposure to blood from an individual with AIDS.11

While HIV transmission from provider to patient is rare, it is possible. The CDC reports risks associated with the transmission of HBV, HCV, and HIV are minimal during exposure-prone procedures and inconsequential with noninvasive procedures.1,2 Based on transmission risk, the CDC groups dental procedures into two categories. Category I includes procedures with a history of provider-to-patient transmission of HBV, and are more likely to pose risk.4 Category I procedures include major oral and maxillofacial surgery, as well as techniques involving the presence of the provider’s fingers and a sharp instrument within an area of poor visibility or small anatomical site. Category II includes all procedures not specified in Category I, and usually poses little to no risk of viral transmission. These techniques are characterized by the use of needles outside of the oral cavity and examination procedures not involving sharp objects.4

PROVIDER-TO-PATIENT TRANSMISSION

Historically, there have been multiple incidents of disease transmission from dental providers to patients in the United States (Table 1), including documented cases of HBV transmission.6 The majority of the providers responsible were oral surgeons. Between 1969 and 1974, an oral surgeon with an HBeAg-positive status infected approximately 55 patients (10 probable; 45 possible).6 Upon investigation, it was discovered the oral surgeon did not wear gloves while treating patients.6 A similar case occurred between 1978 and 1979, but, in addition to not wearing gloves, the oral surgeon had generalized eczematous dermatitis.6

While most incidents of transmission from provider to patient can be attributed to substandard infection control practices, investigators from several cases were unable to identify the route of disease transmission.6 In 1975 and 1980, 46 patients were infected by dental providers with no explanation related to breaches in infection control.6 It is unknown whether these providers were aware of their HBV status.6 The last known documented cases of HBV transmission from provider to patient occurred between 1984 and 1985. This transmission was from a general dentist who claimed to be unaware of his or her viral status and failed to wear gloves.6 As a result, investigators suspected 24 patients were infected.6 These cases all occurred prior to the 1986 CDC recommendation for glove use as standard practice in dentistry.13

Conversely, the only documented incidences of provider-to-patient transmission of HIV in dental settings occurred from 1987 to 1989, when six patients contracted HIV from a general dentist.1,14 Reports indicate the Florida practice had fully incorporated the use of latex gloves and surgical masks as protective barriers, as well as heat sterilization for surgical and heat-resistant instruments.15 Despite adhering to infection control guidelines, transmission of HIV from the dentist to patients still occurred. Neither the infected patients nor the dentist recalled the clinician being injured by a needlestick or cut during these procedures.2,14,15 The dentist did not have hand dermatitis, injuries, or bleeding disorders that could contribute to the elevated risk of transmission.15 The specific nature of HIV transmission in these cases is still unknown.1,14

Comparing the DNA sequences of the HIV strains, five of the infected patients shared genetic similarities with the dentist’s HIV strain, suggesting direct transmission.15 Several years later, a sixth patient was identified as having contracted HIV from this provider during the same period.14 Identifying the source of infection would have been extremely challenging had Florida authorities not been made aware of the dentist’s HIV-positive status. This situation is just one example of the importance of providers disclosing their infectious disease status to an expert review panel prior to performing exposure-prone procedures.

RULES, REGULATIONS AND ETHICAL RESPONSIBILITIES

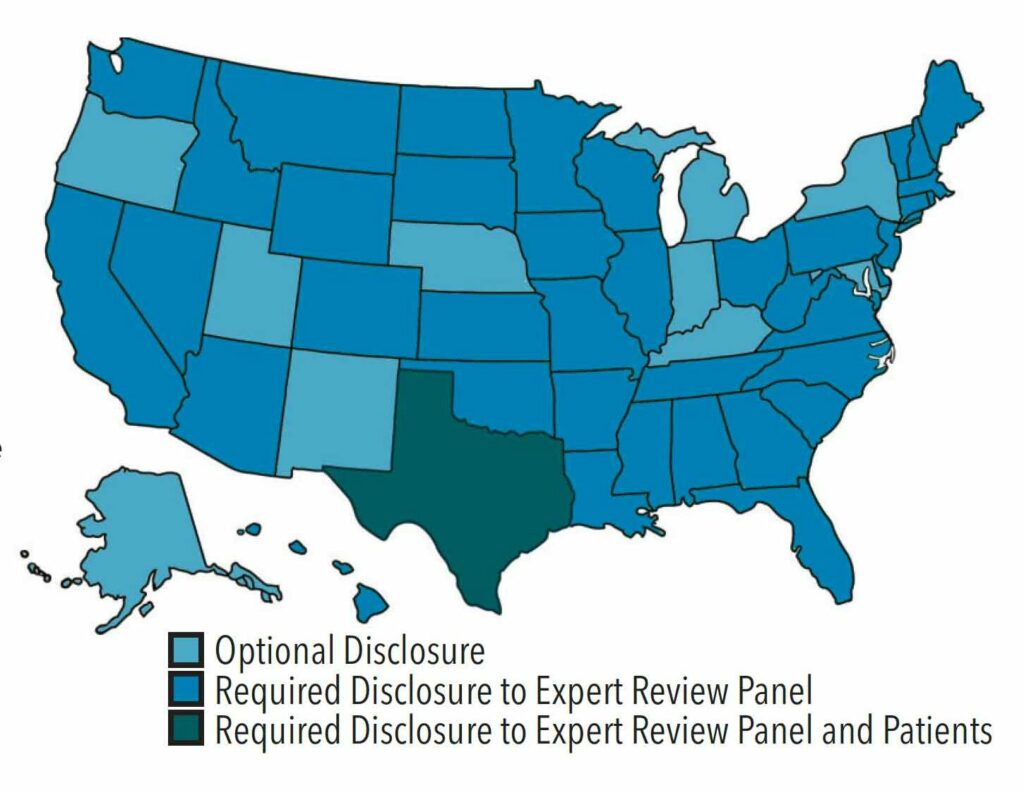

Figure 1 illustrates the difference in state rules and regulations pertaining to infectious disease disclosure.16 Transmission of HIV from a Florida dentist to patients influenced Congress to require states to implement the 1991 CDC guidelines or equivalent guidelines for infection control.2 The majority of states require providers adhere to the most recent CDC Guidelines for Infection Control in Dental Health-Care Settings, published in 2003.3,17 These guidelines recommend providers with HIV and/or HBV refrain from performing exposure-prone procedures until a review panel has been consulted.1,3 Institutional policies should include standard procedures for identifying and convening members of the expert review panel.4 Panel members typically include individuals with expertise in the provider’s area of specialty, epidemiology specialists, human resource professionals, legal counsel, or those familiar with BBP transmission.1,2,4 The expert review panel determines what practice restrictions, if any, will be placed on the provider. In most cases, the infected provider’s viral status, expertise, procedure technique, adherence to standard precautions, and physical ability to safely carry out exposure-prone procedures will all be taken into consideration before the provider may continue to practice.2,4

The CDC does not recommend practice restrictions for providers who have HCV or who do not perform exposure-prone procedures, as the risk of disease transmission is nonexistent during noninvasive procedures.1–3 Currently, Texas is the only state that requires providers with HIV, or HBV with a HBeAg-positive status to take additional measures, including notifying and obtaining written consent from patients prior to performing EPPs.18,19 The consent form should clearly state the potential risks associated with exposure-prone procedures conducted by the infected provider. In Texas, disciplinary actions for noncompliance of infectious disease disclosure to patients may range from a verbal reprimand to license suspension.19

Providers have an ethical obligation to know whether they have an infectious disease.1,2,20 It is their responsibility to receive the three-dose HBV vaccine series, and have their immunogenicity checked 1 month to 6 months after vaccination.1,2,4,5 In 2005, a national survey showed that 89% of respondents (n = 2353) believed it was their right to know if their provider was infected with HIV, and only 38% of those surveyed felt the infected provider should be allowed to provide care.21 These results suggest a patient’s perceived risk of infection may be higher than the actual risk of disease transmission from an infected provider.22

In 1991, when the CDC released infection control guidelines regarding BBPs, it was recommended that providers with HIV or HBV routinely notify patients prior to performing exposure-prone procedures.1,2 Currently, the CDC and Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America suggest that providers with HIV or HBV disclose their status to patients only when there has been a BBP transmission or evidence of high viral load.2,4

The recommendations regarding disclosure have evolved as more studies have shown the low risk of disease transmission from provider to patient when standard precautions are followed. While optional disclosure should be considered, mandatory disclosure to patients could have serious repercussions for the provider, including loss of practice or educational opportunities.2,4

REPORTING LIMITATIONS

There are limitations to identifying and reporting transmission of an infectious disease from providers to patients. One is the lack of disclosure of a provider’s HIV or HBV disease status to an expert review panel and/or patients. Without disclosure, following the chain of transmission to the source of infection can be difficult. The incubation period for HBV can last from an average of 90 days up to 6 months, delaying viral testing and making it more difficult to identify the source of infection.5,15

In the early phase of HIV infection, within 2 weeks to 4 weeks a person will begin to show flu-like symptoms.9 In the Florida case, the first patient presented with flu-like symptoms within 4 weeks of care, and HIV testing was not included in the differential diagnosis due to the patient’s lack of high-risk behaviors.15 Another patient seen by the same dentist did not show early symptoms of HIV until 1 year after the initial visit. During the latency phase of HIV, patients do not typically show symptoms, and progression varies among individuals.9,15 In the first patient’s case, the infection progressed more quickly. In May 1989, the individual was diagnosed with oral candidiasis and in December 1989 with AIDS.15 The AIDS diagnosis occurred approximately 24 months after the dental visit.15 Had the patient known the dentist had HIV, the patient’s HIV diagnosis and subsequent treatment could have been established at an earlier stage of the disease process.

CONCLUSION

At a minimum, HBV-positive or HIV-positive providers have an ethical and professional obligation to disclose their disease status to an expert review panel and, for providers in Texas, obtain written consent from patients. Further research is needed to assess the knowledge, attitudes and compliance of providers related to disclosing their infectious disease status to patients. In order to protect patient health and safety, all healthcare providers must adhere to the standard precautions and ensure they are vaccinated against HBV; in addition, they should be knowledgeable of their vaccination status for all vaccine-preventable infectious diseases. While there are documented cases of infectious disease transmission from provider to patient in the dental setting, these instances are rare. Although the risk of disease transmission from provider to patient is low, clinicians should know their state laws and abide by all facets of infection control and disease prevention. In addition, clinicians with an infectious disease may wish to consider disclosing their status to patients and informing them of the potential risks involved with exposure-prone procedures.

Acknowledgement: The authors thank Kathleen Muzzin, RDH, MS, for her assistance in the development of this manuscript.

REFERENCES

- United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Recommendations for preventing transmission of human immunodeficiency virus and hepatitis B virus to patients during exposure-prone invasive procedures. MMWR Recomm Rep. 1991;40(RR08):1–9.

- Henderson DK, Dembry L, Fishman NO, et al. SHEA guideline for management of healthcare workers who are infected with hepatitis B virus, hepatitis C virus, and/or human immunodeficiency virus. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2010;31:203–232.

- Kohn WG, Collins AS, Cleveland JL, Harte JA, Eklund KJ, Malvitz DM. Guidelines for infection control in dental health-care settings—2003. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2003;52(RR-17):1–61.

- Holmberg SD, Suryaprasad A, Ward JD. Updated CDC recommendations for the management of hepatitis B virus-infected health-care providers and students. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2012;61(RR03):1–12.

- US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Hepatitis B Questions and Answers for Health Professionals. Available at: cdc.gov/hepatitis/hbv/hbvfaq.htm#overview. Accessed February 12, 2021.

- Lewis JD, Enfield KB, Sifri CD. Hepatitis B in healthcare workers: transmission events and guidance for management. World J Hepatol. 2015;7:488–497.

- Bagg J, Roy K, Hopps L, et al. No longer “written off”—times have changed for the BBV-infected dental professional. Br Dent J. 2017;222:47–52.

- US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Hepatitis C Questions and Answers for Health Professionals. Available at: cdc.gov/hepatitis/hcv/hcvfaq.htm#section6. Accessed February 12, 2021.

- US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. About HIV/AIDS. Available at: cdc.gov/hiv/basics/whatishiv.html. Accessed February 12, 2021.

- Bell DM. Occupational risk of human immunodeficiency virus infection in healthcare workers: an overview. Am J Med. 1997;102(5B):9–15.

- Cardo DM, Culver DH, Ciesielski CA, et al. A case-control study of HIV seroconversion in healthcare workers after percutaneous exposure. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Needlestick Surveillance Group. N Engl J Med. 1997;337:1485–1490.

- Ippolito G, Puro V, De Carli G. The risk of occupational human immunodeficiency virus infection in healthcare workers. Italian Multicenter Study. The Italian Study Group on Occupational Risk of HIV infection. Arch Intern Med. 1993;153:1451–1458.

- US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Investigations of persons treated by HIV-infected health-care workers—United States. MMWR Recomm Rep. 1993;42:329–331,337.

- Ciesielski C, Marianos D, Ou CY, et al. Transmission of human immunodeficiency virus in a dental practice. Ann Intern Med. 1992;116:798–805.

- Cleveland JL, Gray SK, Harte JA, Robison VA, Moorman AC, Gooch BF. Transmission of blood-borne pathogens in US dental healthcare settings: 2016 Update. J Am Dent Assoc. 2016;147:729–738.

- The Center for HIV Law and Policy. Guidelines for HIV-positive Health Care Workers, The Center for HIV Law and Policy (2008). Available at: hivlawandpolicy.org/resources/guidelines-hiv-positive-health-care-workers-center-hiv-law-policy-2008. Accessed February 12, 2021.

- Texas State Board of Dental Examiners. Texas Administrative Code. Title 22. Available at: texreg.sos.state.tx.us/public/readtac$ext.TacPage?sl=R&app=9&p_dir=&p_rloc=&p_tloc=&p_ploc=&pg=1&p_tac=&ti=22&pt=5&ch=108&rl=25. Accessed February 12, 2021.

- Texas Health and Safety Code, Title 2. Available at: statutes.capitol.texas.gov/Docs/HS/htm/HS.85.htm. Accessed February 12, 2021.

- Texas Occupations Code. Title 3. Available at: statutes.capitol.texas.gov/Docs/OC/htm/OC.263.htm. Accessed February 12, 2021.

- Tuboku-Metzger J, Chiarello L, Sinkowitz-Cochran RL, Casano-Dickerson A, Cardo D. Public attitudes and opinions toward physicians and dentists infected with bloodborne viruses: results of a national survey. Am J Infect Control. 2005;33:299–303.

- Mellinger JL. What is the moral responsibility of healthcare providers to report HBV or HCV status if they perform invasive procedures? Clin Liver Dis (Hoboken). 2015;6:92–95.

- US Centers for Disease Control. Recommended infection-control practices for dentistry. MMWR Recomm Rep. 1986;35:237–242.

From Dimensions of Dental Hygiene. March 2021;19(3):40-43.