ROST-9D/ISTOCK/GETTY IMAGES PLUS

ROST-9D/ISTOCK/GETTY IMAGES PLUS

Understanding Fragile X Syndrome

Strategies for the safe and effective treatment of patients with this type of inherited intellectual disability.

This course was published in the March 2021 issue and expires March 2024. The author has no commercial conflicts of interest to disclose. This 2 credit hour self-study activity is electronically mediated.

EDUCATIONAL OBJECTIVES

After reading this course, the participant should be able to:

- Describe the history of fragile X syndrome (FXS).

- Identify the pathophysiology of FXS.

- Discuss strategies for providing oral healthcare to this patient population.

Fragile X syndrome (FXS) is the most common form of inherited intellectual disability.1–6 Linked to the X chromosome, it is inherited by females who carry the premutation allele. Individuals with FXS either do not manufacture at all or do not manufacture enough of the fragile X mental retardation 1 protein, which is integral to healthy brain development.7 FXS occurs most commonly in males (~one in 4,000 to ~one in 7,000); it’s occurrence in females is about one in 6,000 to one in 11,000.2,6–9

FXS occurs among all ethnic groups, although it is more prevalent in whites than Black or Native American populations, and those of Asian descent are significantly less likely to be affected.4,10,11 The related cognitive impairments include a low IQ (< 40), behavioral problems, and social deficiencies. The physical characteristics of FXS include a long forehead and prominent ears. A highly arched palate is often noted, leading to crowding and malocclusion.10–13

Accurate diagnosis can be challenging, and many parents will take their children to a physician more than 10 times before a diagnosis is reached.10 Further complicating the diagnosis is the fact that autism spectrum disorder (ASD) is a comorbid condition with FXS, exhibiting many of the same signs and symptoms. Confirmation of an FXS diagnosis is achieved through a DNA test. While autism can be caused by many different genes, FXS is the most common single-gene mutation to cause autism.13,14

HISTORY

FXS was first discovered as an inherited disability related to the X chromosome by Martin and Bell in1943. However, it wasn’t until 1969 that the fragile site on the X chromosome was identified. Caused by an abnormal fragile X mental retardation 1 (FMR1) gene, it creates an unstable repeat of cytosine-guanine-guanine (CGG).7,10 The normal amount of CGG repeats is between five and 40. A person with FXS may either have a premutation—an expanded nucleotide that repeats long enough to make a person a carrier—of 55 repeats to 200 repeats, or a full mutation of more than 200 repeats.10 Most carriers of the premutation are asymptomatic, but can be prone to other symptoms later in life, such as anxiety, depression, and insomnia.5,6,15 In addition, female carriers may develop fragile X-associated primary ovarian insufficiency (menopause prior to age 40). Male carriers may exhibit attention and behavioral difficulties, as well as fragile X-associated tremor/ataxia syndrome (FXTAX) after age 50. FXTAX is similar to Parkinson disease and presents with tremors, increased risk of dementia, and heightened fall risk.5,10,12,13,16 Oral health professionals should be mindful of treating patients at fall risk as many offices have rugs, carpets, foot petals, and cords that may present a fall hazard. Amplifying this fall risk, medications used to treat FXS can cause orthostatic hypotension, so it is important to allow patients to sit upright prior to standing.

PATHOPHYSIOLOGY

The pathophysiology of FXS is characterized by cognitive impairments with men being the most impacted. Women with FXS present with less severe symptoms.6,17 Only about 30% to 50% of women with FXS exhibit severe symptoms, and they may have a normal IQ.8,13 However, women with FXS may experience exaggerated mood changes influenced by strong feelings.10 Later in life, almost 50% of women with the full mutation will live independently, whereas only about 10% of men will be able to achieve this goal.6

Symptoms of FXS are similar to ASD: hyperactivity, developmental delays, difficulty communicating, unique physical behaviors (eg, hand flapping), behavioral problems, and hypersensitivity to sensory input.2,5,6,9,18 When ASD is present in someone with FXS, the symptoms tend to be more severe, and there is a higher prevalence of social withdrawal. In addition, patients with FXS are more likely to experience seizures than the general population. About 13% to 18% of men and 5% of women will have a seizure disorder. The risk of seizures is greater if the patient is co-diagnosed with ASD.2,10,13 As such, the dental team needs to take a detailed medical history and be prepared to handle a medical emergency. Patients with seizure disorders should be asked about the types of seizure they experience—for example, seizures can be characterized by presenting motor function (tonic-clonic seizure), or nonmotor function (absence seizures).19 Documenting whether a patient takes his/her medication regularly and the date of his/her last seizure is important. Depending on the type of neurological disorder (epilepsy), the longer patients go without a seizure, the less likely they are to have one.20 Lastly, knowing if the patient experiences auras is crucial. Sunglasses can be provided to protect him/her from bright lights, which can signal an aura.

Although treatment planning for all patients should consider individual needs, additional measures are necessary when treating those with FXS. Their often complicated medical histories coupled with intellectual challenges and seizure risk create particular challenges for oral health professionals.21 Individual adjustments for a patient with FXS may include interprofessional collaboration and longer appointments. During the assessment phase, the patient’s caregiver should be thoroughly interviewed as he or she knows the individual best. After the interview, a thorough evaluation and documentation should include the patient’s preferences, dislikes, and triggers for poor behavior. Further, common oral manifestations may impact treatment. The common oral findings in patients with FXS show large variability, but include a narrow palate and long face, macroglossia, microdontia, supernumerary teeth, and abnormal occlusion (eg, open or cross-bite).22

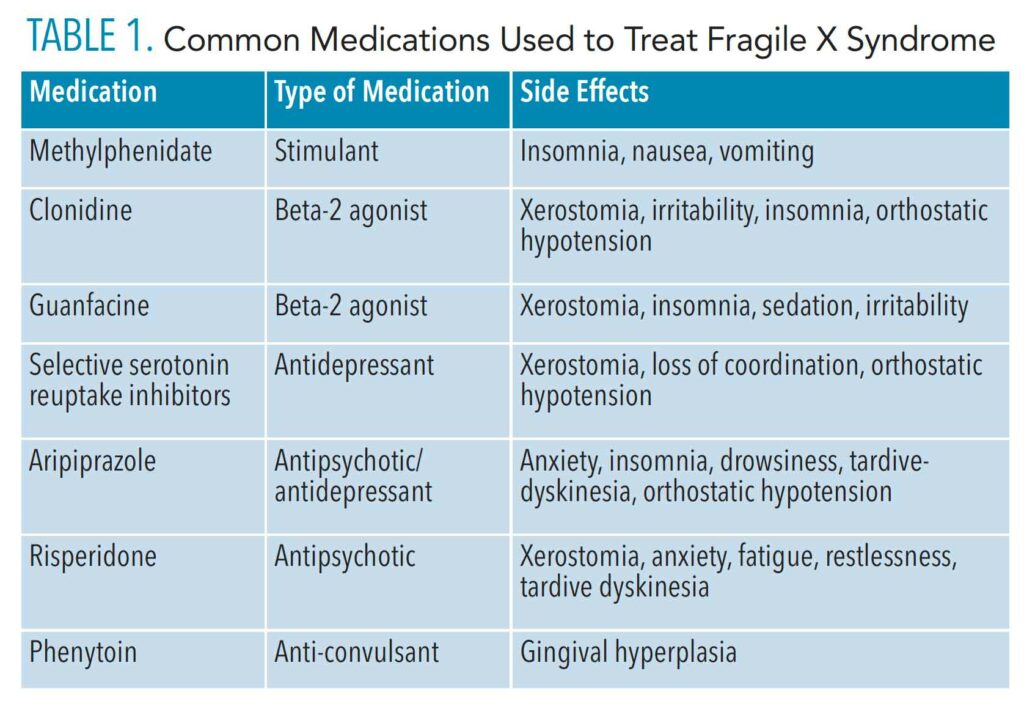

![table 1]() MEDICATIONS

MEDICATIONS

In more than 50% of individuals with FXS, behavioral problems—such as anxiety, depression, aggression, and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder—are evident.2,5,7,10,23 Obsessive-compulsive and self-injurious behaviors may also be present.10,23 Medications used to treat FXS (Table 1) often cause xerostomia, which can lead to further problems in the oral cavity. If the patient is receiving treatment for seizures, these medications could cause gingival hyperplasia. Psychoactive drugs are often used to address aggression or other severe dysfunctional symptoms, and also in individuals co-diagnosed with both FXS and ASD.

Common medications used to treat patients with FXS include methylphenidate for hyperactivity; clonidine and guanfacine (hyperactivity and hypersensitivity to stimuli); and selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) and/or aripiprazole for depression, anxiety, emotional lability, and other mood disorders.10,13,23,24 Aripiprazole and risperidone may also induce tardive-dyskinesia, which causes involuntary muscle movement—an undesirable side-effect in the dental chair.10,25 SSRIs can also help with obsessive disorders.

Occasionally, a patient taking a stimulant may experience an increase in his or her anxiety or aggression. The risk of aggressive behavior should always be considered when treating patients with FXS. Caregiver reports suggest > 90% of patients with FXS have exhibited aggression over a 12-month period.24 This tendency toward aggression will likely increase in the dental office, as it is an unfamiliar environment increasing anxiety. Further, hypersensitivity to stimuli can also trigger the potential for aggression. When patients with FXS are aggressive, redirection is a treatment option that can be easily implemented in the dental office.23 For example, if the dental office has a television, direct the patient to what is on the television rather than the dental appointment. Another alternative might be to give the patient a book or magazine to look at. Ensuring good communication with the caregiver is important in understanding the treatment plans that may suit the individual best.

ORAL HEALTHCARE

Routine dental hygiene care is necessary for patients with FXS; however, people with special healthcare needs are often underserved in the dental office.26 Due to hypersensitivity to stimuli, a patient with FXS presents particular challenges when visiting the dental office. This hypersensitivity to stimuli is also increased with a co-diagnosis of ASD.9 Oral health professionals need to slowly introduce these patients to the dental office, and more than one appointment may be necessary. Desensitization is vital to avoid any traumatic experiences.

Prior to visiting the dental office, patients with FXS may benefit from advance preparation from their caregivers. This could include having the caregiver use a dental mirror in the patient’s mouth, and then counting the teeth.26 Touch aversion, loud or strange noises, and bright lights will present difficulties for patients with FXS. FXS-induced hypersensitivity to stimuli can also increase anxiety, which may lead to temper tantrums or other negative behaviors.5 When possible, playing a familiar show or video during the appointment may provide a calming effect in the dental office. Noise canceling headphones and sunglasses should be considered. A lead apron applied during treatment may also calm patients, as pressure can sometimes help with anxiety.26

Hypersensitivity to stimuli presents specific considerations outside of the dental office as well. Patients with FXS may have feeding problems because certain textures are avoided. In addition, these patients are at high risk for gastroesophageal problems caused by allergies (eg, gluten or milk protein).10,27 Oral health professionals may want to suggest allergy testing. Gastrointestinal problems can also be caused by medications commonly taken by patients with FXS. As such, a semi-supine dental position should be recommended.28

Patients with FXS may be averse to toothbrushing because of the texture or taste. Oral health professionals need to help desensitize patients to toothbrushing and a consultation with an occupational therapist or applied behavioral therapist could help with this issue.23 Finally, the needs of caregivers should also be considered when evaluating a patient with FXS, as caring for a special-needs patient can be challenging. A good resource to explore is the National Institutes of Health Genetics and Rare Diseases Information Center29 at: rarediseases.info.nih.gov/guides/pages/120/support-for-patients-and-families.

In general, children with special healthcare needs are thought to be underserved in the dental community, and dental care is this population’s largest unmet need.17,18,30 However, one study showed children with FXS visit the dentist as often as the general population.17 With any intellectual disability, oral health professionals can expect poor oral hygiene, and higher prevalence of periodontitis than the normal population.18,31–34 One study showed periodontitis affected more than 92% of those with intellectual disabilities older than 60.31

Untreated caries can also be a significant problem in this population.32,33 Fluoride varnish should be applied every 3 months, and sealant application and a prescription fluoride dispensed under the supervision of the caregiver should be considered.34 Products containing xylitol to decrease caries risk and saliva replacements may also be helpful. Finally, silver diamine fluoride (SDF) to arrest caries lesions is a simple and effective strategy for these patients.

Poor oral hygiene in individuals with FXS is common, so a dynamic and tailored oral hygiene regimen is recommended depending on the touch aversion of the patient and skill of the caregiver. For example, interdental brushes might be easier to use than floss, or a nonalcohol-based mouthrinse can be recommended for medication-induced xerostomia. Written instructions will improve caregivers’ confidence to help their loved ones maintain oral hygiene routines.

CONCLUSION

Oral health professionals may likely treat patients with FXS, as it is the most common form of inherited intellectual disability. Not only are its symptoms similar to autism, those with FXS are also far more likely to have autism.

Behavioral manifestations that may present in the dental practice include social withdrawal, aggression, anxiety, and hypersensitivity to stimuli. A dental appointment is a significant event in someone with FXS. Preparatory work on the part of the caregiver should be considered, and the dental team should be apprised of strategies to help the appointment go as smoothly as possible. Medications taken by patients with FXS will also impact dental treatment, raising the risk of xerostomia and gingival hyperplasia, as well as increasing anxiety and irritability.

The periodontium may also suffer in patients with FXS. Poor oral hygiene, periodontitis, and caries are common. Fluoride varnish, prescription fluoride toothpaste, and SDF should be considered. Specialized and dynamic oral hygiene instruction should be suggested depending on what the patient is able to tolerate and what the caregiver is able to perform.

REFERENCES

- Raspa M, Wheeler AC, Riley C. Public health literature review of fragile X syndrome. Pediatrics. 2017;139:S153–S171.

- Kaufmann WE, Kidd SA, Andrews DB, et al. Autism spectrum disorder in fragile X syndrome: concurring conditions and current treatment. Pediatrics. 2017;139:S194–S206.

- Kraan CM, Godler DE, Amor DJ. Epigenetics of fragile X syndrome and fragile X-related disorders. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2007;8:109–129.

- Owens KM, Dohany L, Holland C, et al. FMR1 premutation frequency in a large, ethnically diverse population referred for carrier testing. Am J Med Genet A. 2018;176:1304–1308.

- Hagerman RJ, Protic D, Rajaratnam A, Salcedo-Arellano MJ, Aydin EY, Schneider A. Fragile X-associated neuropsychiatric disorders (FXAND). Front Psychiatry. 2018;9:564.

- Hunter J, Rivero-Arias O, Angelov A, Kim E, Fotheringham I, Leal J. Epidemiology of fragile X syndrome: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Med Genet A. 2014;164:1648–1658.

- United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. What Is Fragile X Syndrome? Available at: cdc.gov/ncbddd/fxs/facts.html. Accessed February 21, 2021.

- Sherman SL, Kidd SA, Riley C, et al. Forward: a registry and longitudinal clinical database to study fragile X syndrome. Pediatrics. 2017;139:S183–S193.

- Raspa M, Wyle A, Wheeler AC, et al. Sensory difficulties in children with an FMR1 premutation. Frontiers in Genetics. 2018;9:351.

- American Academy of Pediatrics. Health Supervision for Children With Fragile X Syndrome. Available at: pediatrics.aappublications.org/content/pediatrics/127/5/994.full.pdf. Accessed February 21, 2021.

- Genereux DP, Laird CD. Why do fragile X carrier frequencies differ between Asian and non-Asian populations? Genes Genet Syst. 2013;88:211–224.

- Saul RA, Tarleton JC. FMR1-related disorders. Gene Reviews. Available at: ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/ books/NBK1384. Accessed February 21, 2021.

- Garber K, Visootsak J, Warren S. Fragile X syndrome. European Journal of Human Genetics. 2008;16:666–672.

- Niu M, Han, Y, Dy ABC, et al. Autism Symptoms in Fragile X Syndrome. J Child Neurol. 2017;32:903–909.

- Mila M, Alvarez-Mora MI, Madrigal I, Rodriguez-Revenga L. Fragile X syndrome: an overview and update of the FMR1 gene. Clin Genet. 2018;93:197–205.

- Sherman S, Pletcher BA, Driscoll DA. Fragile X syndrome: diagnostic and carrier testing. Genet Med. 2005;7:584–587.

- Gilbertson KE, Jackson HL, Dziuban EJ, et al. Preventative care services and health behaviors in children with fragile X syndrome. Disabil Health J. 2019;12:564–573.

- Mirsky LB, Gurenlian J. Treating patients with autism spectrum disorders. Dimensions of Dental Hygiene. 2018;16(2):46–49.

- Pack AM. Epilepsy overview and revised classification of seizures and epilepsies. Continuum (Minneap Minn). 2019;25:306–321.

- National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke. The Epilepsies and Seizures: Hope Through Research. Available at: ninds.nih.gov/Disorders/Patient-Caregiver-Education/Hope-Through-Research/Epilepsies-and-Seizures-Hope-Through#top. Accessed February 21, 2021.

- Gurenlian JR, Swigart DJ. Dental hygiene diagnosis. Dimensions of Dental Hygiene. 2018;16(12):36–39.

- Sabbagh-Haddad A, Haddad DS, Michel-Crosato E, Arita ES. Fragile X syndrome: panoramic radiographic evaluation of dental anomalies, dental mineralization stage, and mandibular angle. J Appl Oral Sci. 2016;24:518–523.

- Wheeler AC, Raspa E, Bishop E, Bailey DB. Aggression in fragile X syndrome. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research. 2016;60:113–125.

- Berry-Kravis E, Potanos K. Psychopharmacology in fragile X syndrome—present and future. Ment Retard Dev Disabil Res Rev. 2004;10:42–48.

- National Institutes of Health. Practical Oral Care for People with Autism. Available at nidcr.nih.gov/sites/default/files/2017-09/practical-oral-care-autism.pdf. Accessed February 21, 2021.

- Hernandez P, Ikkanda Z. Applied behavior analysis: behavior management of children with autism spectrum disorders in the dental environment. J Am Dent Assoc. 2011;142:281–287.

- Rada RE. Controversial issues in treating the dental patient with autism. J Am Dent Assoc. 2010;141:947–953.

- Jeske AH. In: Mosby’s Dental Drug Reference. 12th ed. St. Louis: Elsevier: 2018.

- National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences. Genetic and Rare Diseases Information Center. Available at: rarediseases.info.nih.gov/guides/pages/120/support-for-patients-and-families. Accessed February 21, 2021.

- Lewis CW. Dental care and children with special health care needs: a population-based perspective. Acad Pediatr. 2009;9:420–426.

- Zhou N, Wong HM, Wen YF, Mcgrath C. Oral health status of children and adolescents with intellectual disabilities: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2017;59:1019–1026.

- Ward LM, Cooper SA, Hughes-McCormack L, Macpherson L, Kinnear D. Oral health of adults with intellectual disabilities: a systematic review. J Intellect Disabil Res. 2019;63:1359–1378.

- Anders PL, Davis EL. Oral health of adults with intellectual disabilities: a systematic review. Spec Care Dentist. 2017;39:146–155.

- Azarpazhooh A, Main PA. Fluoride varnish in the prevention of dental caries in children and adolescents: a systematic review. J Can Dent Assoc. 2008;74:73–79.

From Dimensions of Dental Hygiene. March 2021;19(3):36-39.