Determining Identity Through Dental Forensics

Dimensions of Dental Hygiene speaks with renowned dental forensic scientist, Gerald L. Vale, DDS, MDS, MPH, JD, about how these dental detectives uncover or corroborate the identity of victims.

How did you get into the field of forensic dentistry?

After having an orthodontic practice for about 18 years, I decided to pursue additional studies and earned degrees in both public health and law. I was interested in forensic dentistry, having heard about dental evidence being used in legal matters. Then, by chance in 1968, I was contacted by the coroner’s office when a helicopter crashed en route from Los Angeles International Airport to Disneyland, killing 21 people. I was asked to assist in the investigation. I did and was able help identify those who died.

With the popularity of the television show “CSI,” has interest in forensics increased?

Yes, certainly the “CSI” series is incredibly popular and, of course, this has increased the general public’s interest in forensic science. The show’s influence on forensic science has been good and bad. The good is that the public is more aware of what can be accomplished with forensics. On the other hand, people have also developed some unrealistic ideas about the ease and speed with which forensic science works. This has put some pressure on forensic scientists.

Historical Perspective

The use of dental records has long been the mainstay of forensics. When did this first become an important means of identification?

The first solid historical evidence of the use of dental evidence goes back to 49 AD when Agrippina, mother of the Roman Emperor Nero, reportedly had a lady named Lollia Paulina murdered for reasons that are unclear. According to historical reports, Agrippina had Lollia’s head brought to her to ensure that the murder had really taken place. Supposedly, she identified the head by an irregularity in the formation of the teeth.

The first well documented case in the United States dealt with Paul Revere. Revere created a denture—a silver wire fixed bridge—for General Joseph Warren. He made the appliance in 1775. Shortly thereafter Warren was killed in the battle of Bunker Hill and his body was buried and subsequently exhumed. In 1776, Revere examined the exhumed body and was able to easily recognize General Warren by the silver wire appliance that he had placed just 1 year earlier.

The first case in the American judicial system in which dental evidence was introduced in court and accepted as a reliable means of identification dealt with a very prominent figure at Harvard Medical School. A professor of chemistry at Harvard named Dr. John Webster began borrowing money from his friend, Dr. George Parkman. Parkman was an extremely wealthy man and a major benefactor of the Harvard Medical School. The medical school building was about to be dedicated to Dr. Parkman and he was to make a speech acknowledging this honor. In preparation, he hastily had a full denture made for the occasion. Subsequently, he and Webster got into a dispute over the money Webster owed him. Webster allegedly murdered Parkman, whose body was found incinerated in the chemistry building. Thus, Parkman’s denture became important evidence. Parkman’s dentist was called in to identify the denture and, in that manner, the crime was established and the remains of the body were identified. Since then, there have been many well known cases involving dental evidence.

On the Job

When is forensic dentistry needed to establish identification?

A victim’s body may be severely burned, decomposed, or bloated. Such conditions may make the person unrecognizable and may also destroy the friction ridges on the fingers, eliminating the possibility of fingerprint evidence. Also, the body may have been mutilated and the fingers, hands, or head may have been removed, causing similar problems. Even if the fingers are intact, fingerprint evidence cannot establish identity if there are no prints of the suspected victim on file for comparison. In all of these cases, the use of dental evidence and/or DNA comes to the fore.

How is the identification made?

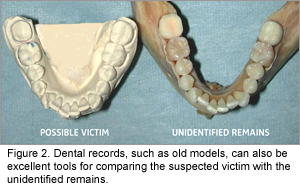

All relevant evidence should be recovered from the disaster site. A thorough clinical examination of the remains is then performed. This includes radiographs, photographs, and dental charting. There is usually some clue as to who the victim may be, so efforts are made to obtain complete antemortem dental records from the victim’s dentist. Ideally, this should include at least the radiographs and chart, since the chart may disclose treatment performed after the x-rays were taken. In some cases old diagnostic or work models, old dentures, bleaching trays, or other records may be of great value (Figures 1, 2 and 3). If dental records cannot be obtained, smiling photographs of the victim sometimes show distinctive dental features that can be compared to the remains. In any comparison, all dental features that can be compared must be considered, including the presence or absence of teeth and restorations or prostheses; the shape of roots, crowns, and restorations; height, contour, and detailed appearance of bone; contour of the floor of the maxillary sinus, etc. The number of similar characteristics should be considered and whether they are unusual or commonplace. If some features do not seem to match, it must be determined if these are merely explainable discrepancies or mismatches that defeat identification.

Do you also use bitemarks to identify people?

In my opinion, this is the most fascinating part of forensic dentistry. First of all, bitemarks are a critically important matter in a criminal trial in which such evidence is available. If bitemark evidence is part of the case, it is often the key evidence. The reason it is so fascinating is because it’s extremely challenging. There are basic issues as to how well you can individualize a set of teeth as a result of a mark left on skin. The reality is that there is usually not enough information to make it possible to specifically identify a person (Figure 4). But in the relatively rare cases where the bitemark is really clear—providing a lot of information about the biter’s teeth—it can be very powerful. If you can establish to the satisfaction of the jury that the bitemark on the body of a rape/murder victim was indeed inflicted by the defendant, you’ve put the defendant at the scene of the crime and established that he or she acted violently toward the victim. If the jury accepts both of those concepts, they are very likely to accept the ultimate concept, namely that this is the person who committed the crime.

Getting Involved

Can dental hygienists play a role in forensic dentistry?

Yes. Historically, the participation of dental hygienists has varied, depending on the nature of the disaster, the surrounding circumstances, and the views of the forensic dentist in charge. My opinion is that the dental hygienist has the skills to contribute significantly in the important examination and charting procedures, either by working as a member of the charting team or by performing a preliminary examination. In the important process of radiography, the hygienist might organize and

| For more information on forensic dentistry, visit these links: |

| American Academy of Forensic Sciences www.aafs.org

American Board of Forensic Odontolog www.abfo.org American Society of Forensic Odontology www.forensicdentistryonline.org Armed Forces Institute of Pathology www.afip.org Southwest Forensic Science Symposium, University of Texas, Health Science Center http://ddsdx.uthscsa.edu/ContEd.html |

supervise this activity and/or take radiographs. The dental hygienist is ideally qualified to handle the equally important task of controlling the flow and security of the records that seem to almost fill the air in a mass fatality incident. Finally, the hygienist is well suited to keep administrative records of the investigation itself. In addition, there are plans to expand dentistry’s emergency activities to include responding to bioterrorism and providing emergency medical care. Such plans may offer opportunities for all members of the dental team to take additional training to provide emergency response to natural and man-made emergencies.

Will forensic dentistry play a role in hurricane Katrina’s aftermath?

Absolutely. Members of the Disaster Mortuary Operational Response Team (DMORT), which includes dental hygienists as members, are currently attempting to identify the hundreds of bodies found so far. These dental professionals have trained to provide disaster response and have served in other disasters like the World Trade Center. When deployed for duty, they become federal employees under the Department of Homeland Security. By September 17, they had reportedly examined approximately 450 bodies. Identification will be challenging, as many of the bodies reportedly have one or more edentulous jaws and arrived without dentures. Obtaining dental records will be a problem. In addition to the usual difficulties, some dental records have been engulfed by floodwater. Whatever identifications can be made will eliminate agonizing uncertainties and, hopefully, help families and loved ones move forward with their lives.

For hygienists who would like to offer their services in the face of a disaster in this country or their local area, how do they go about volunteering?

The first step is to take some training. Two excellent courses are the Forensic Dental Identification Course given by the Armed Forces Institute of Pathology in Bethesda, Md, and the Southwest Forensic Science Symposium given by the University of Texas, Health Science Center in San Antonio. Shorter courses are also offered by dental schools and coroner’s offices throughout the country. Volunteering can be challenging. It is best, if possible, for the dental hygienist to become affiliated with a local forensic dental team through the coroner’s office, a state dental identification team, or DMORT. The United States Department of Health and Human Services has a website dedicated to volunteer information at: https://volunteer.ccrf.hhs.gov.

From Dimensions of Dental Hygiene. October 2005;3(10):12, 14, 16-17.