Dental Detectives

Dental hygienists have much to offer the forensic dental team in the postmortem identification process.

This course was published in the November 2012 issue and expires November 2015. The authors have no commercial conflicts of interest to disclose. This 2 credit hour self-study activity is electronically mediated.

EDUCATIONAL OBJECTIVES

After reading this course, the participant should be able to:

- Explain the methods used to identify human remains.

- Discuss the role that dental hygienists play on the dental forensic team.

- Identify the technological advances made in forensic dentistry.

Forensic dentistry has served to identifydeceased individuals since the reign of Nero in the Roman Empire.1 The first forensic dental identification made in the United States was by Paul Revere, a silversmith and dentist. He identified an ivory and silver bridge he had fabricated 2 years earlier for Joseph Warren, MD—the first American officer killed in the Battle of Bunker Hill—whose remains were discovered in a British mass grave.2

Human psychology drives the desire to identify the dead, which makes the forensic identification process crucial in meeting this challenge.2 Roles in forensic dentistry have traditionally been filled by dentists, however, dental hygienists have much to add to the forensic dental team and play a key role in the antemortem (AM) and postmortem (PM) phases of identification.3

IDENTIFICATION METHODS

Forensic odontology is the management, examination, evaluation, and presentation of dental evidence in criminal or civil legal matters. The identification of human remains occurs through comparison of AM and PM dental profiles. Cases typically involve individual deaths with legal ramifications or multiple casualties in mass disasters. The forensic dental team is called into action by a medical examiner or coroner when traditional methods of identification fail.2 Forensic dentistry teams are responsible for six areas of expertise: identification of individual human remains, identification of mass fatalities, assessment of bite mark injuries, assessment of abuse cases (child, spousal, and elder), civil cases of malpractice, and age estimation.4

Identification methods are divided into two subgroups: presumptive and scientific. Presumptive identifiers include circumstantial, visual, serology, personal effects, and tattoos. Often, these identification methods are not considered sufficient, although they contribute to an identity profile and serve as the primary source for a “believed to be” (BTB) identity, which provides a starting point for investigation into AM dental records. Scientific identification methods consist of DNA, fingerprints, dental records, and unique identifiers, such as implanted medical devices with serial numbers.2 DNA is a unique identifier, however, it requires sensitive laboratory processing and an AM specimen or family reference sample. The total amount of time and resources required for a positive DNA identification is greater than those of fingerprinting or dental identification. Fingerprint identification is relatively rapid, but requires AM fingerprints for comparison and may be limited by body decomposition.

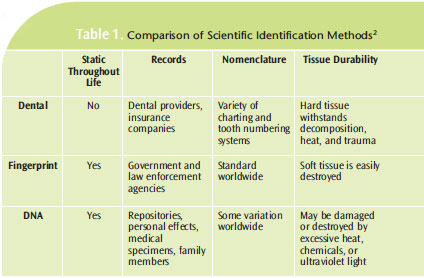

While dental identification is not always available, it provides a rapid, positive identification, unaffected by decomposition. 2 Dental enamel represents the hardest and most resilient tissue in the human body. Tooth structure is capable of surviving in fire up to 1,600°F, leaving a high percentage of dental recovery. The ability to obtain AM dental records and radiographs is also highly probable.1 Table 1 provides a comparison of these scientific identification methods.2

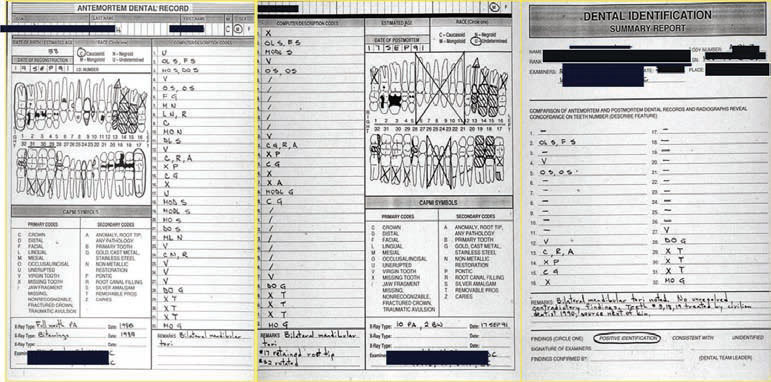

The forensic dental team is likely to encounter difficulties when adequate dental records or current radiographs are unavailable. Some private offices rely strictly on documentation and do not maintain a current oral or complete oral hard tissue chart. Additionally, dental charting is not standardized and black and white (instead of color–coded) charts require additional examination. More variety of radiographs (panorex, bitewings, and full mouth series) and distinctly marked right or left sides increases a forensic dental team’s options during the identification process, particularly in cases of skeletal mutilation.1 Prior to examining any remains, an AM record is constructed based on available dental records, charts, radiographs, and supporting information. During a forensic examination, a PM record is developed by viewing PM radiographs and cadaver examination.1 Examiners compare AM and PM records to prepare a written summary of conclusions, clarification of charting discrepancies, list pertinent findings, and describe the identification classification: positive identification, consistent with, or unidentified. This summary is then presented to the medical examiner or coroner (Figure 1). The American Board of Forensic Odontology defines a positive identification as one where the AM and PM identifiers have sufficient matching data with no irreconcilable differences.

When AM and PM data express consistent features, but a positive identification is not possible due to either quality of PM remains or AM evidence, an identification is listed as being “consistent with” a certain individual. An unidentified identification is selected when information is insufficient to form a conclusion.2

PART OF THE TEAM

Dental hygienists have knowledge and specific skills that are valuable to the forensic odontology team during the AM, PM, and comparison processes. Dental hygienists provide administrative skills and are responsible for handling sensitive information during AM dental record requests.5 In order to compile an accurate AM record, adequate dental records are required. Clinical dental hygienists provide the first line of AM documentation because they are responsible for creating and maintaining a dental chart on each patient.6 Clinical dental hygienists should ensure that all existing patients have an electronic or paper dental chart of existing restorations, oral anomalies and pathologies, and periodontal conditions, in addition to documentation on treatment provided, that is updated at each appointment. This record should also include documentation of scars, tattoos, and lesions noted during a comprehensive extraoral and intraoral examination. Additionally, clinicians should ensure that all patients have a variety of radiographs (eg, panorex, bitewings, and full mouth series) in current standing.7 Radiographs should always be diagnostically and clinically sound. The clinical dental hygienist’s role in determining the need for radiographs and considering current standards for X–ray exposures ensures complete and accurate records of a patient’s oral conditions, which are crucial to the forensic dental team. Maintaining adequate charts, documentation, and current radiographs prevents the need for identifiers to make additional efforts and eliminates difficulties.5

Dental hygienists can also complete a PM chart during the forensic odontologist’s examination. Remains long deceased, recovered after fire, or exposed to elements require cleaning with a hydrogen peroxide solution to remove debris and expose dentition. This task often falls to dental hygienists for effective and time-efficient removal of residue from the remains (Figure 2). Rigor mortis inhibits identifiers from accessing the oral cavity properly for radiographs or examination. Forensic dental hygienists may employ different techniques in an attempt to open the oral cavity, including sliding tongue depressors between teeth to open the occlusion or using a Henning cast spreader (Figure 3). When it is necessary to resect the jaw or facial tissues, adequately trained dental hygienists may request permission from the medical examiner to assist the forensic odontologist during the surgery (Figure 4). After gaining proper access to the oral cavity, dental hygienists can take a PM full–mouth radiographic series on the remains.

Dental hygienist’s knowledge of dental anatomy and root morphology is valuable to forensic odontologists when comparing AM and PM dental charts and radiographs. Forensic dental hygienists may chart the identification summary, while forensic dentists report to the medical examiner. Fluency in dental language allows dental hygienists to communicate and assist authorities (FBI, state/local police departments, medical examiner) in procuring any supplemental dental evidence necessary for positive identification, including spare prosthetic devices or laboratory prescriptions from dental offices, laboratories, and family members.

ADVANCES IN TECHNOLOGY

Technology also allows the dental forensic team to become mobile and process remains on-site using portable battery–powered/electric X–ray tube heads and a laptop computer equipped with a dental digital imaging system (Figure 5).2

The use of computer programs or identification databases, such as WinID, the National Crime Information Center, and the United States Justice Department’s National Missing and Unidentified Persons Systems, has improved the process of forensic identification. When a positive identification is not possible, forensic charts may be entered into these databases or computer programs, linking law enforcement officials and medical examiners across the country in the search for missing and unidentified remains. While all three systems are different, dental hygienists can transfer PM forensic charts into the system for possible future identification by another forensic specialist.2 Furthermore, dental hygienists with advanced forensic knowledge and experience may provide administration and managerial leadership to the forensic team and monitor other team members for signs of psychological stress and fatigue—a common, and often overlooked, complication of disaster participation.5

CONCLUSION

The American Society of Forensic Odontology and American Board of Forensic Odontology both recognize the valuable role that dental hygienists can play as part of forensic odontology teams.8 Formal dental hygiene education and advanced specialty training in forensics prepare dental hygiene professionals for multiple roles in the forensic identification process.7 Dental hygienists are involved in disaster mortuary operational response teams (DMORTs) and both national and state level mass fatality response units. Those with forensic identification experience also consult on cases for coroners’ and medical examiners’ offices.8

Dental hygienists interested in dental forensics should pursue additional education and training in the field. Continuing courses in mass casualty and forensic dentistry are key. Basic courses in forensic sciences and medico–legal investigation are strongly recommended due to the specialized knowledge necessary to participate in a forensic investigation. A simple internet search will provide access to local DMORTs or state multiple fatality/ identification teams. On forensic dental teams, the term “dental assistant” is often used for positions that are filled by dental hygienists since they support the forensic dentist.8 Interested professionals can also contact the office of their local coroner or medical examiner to offer their services assisting in forensic identification cases.2 With advanced training, many opportunities are available for dental hygienists to serve as members of a forensic dental team.5

REFERENCES

- Herschaft EE. Manual of Forensic Odontology. 4th ed. Boca Raton, Fla: CRC Press; 2011.

- Colon JE. Introduction to Forensic Odontology. Paper presented at: 44th Annual Forensic DentalIdentification and Emerging Technologies Course; August 2008; Bethesda, Md.

- Cukovic–Bagic I, Di Vella G, Lepore MM, Montagna F, Nuzzolese E. Forensic sciences and forensicodontology: issues for dental hygienists and therapists. Int Dent J. 2008;58:342—348.

- Dolinak D, Lew E, Matshes E. Forensic Pathology: Principles and Practice. New York: Academic Press;2005: 605—629.

- Brannon RB, Connick CM. The role of the dental hygienist in mass disasters. J Forensic Sci.2000;45:381—383.

- Voelker MA. The dental investigation: dental forensics and the role of the dental hygienist.Dimensions of Dental Hygiene. 2009;7(10):58—61.

- Craig BJ, Ferguson DA, Sweet DJ. Forensic dentistry and dental hygiene: how can the dentalhygienist contribute? Canadian Journal of Dental Hygiene. 2008;42(4):203—212.

- Brookshire T. Chaos to Resolution: The Dental Professional’s Role in Mass Fatality and Forensics.Paper presented at: 89th Annual Session of the American Dental Hygienists’ Association; June 2012;Phoenix.

From Dimensions of Dental Hygiene. November 2012; 10(11): 50–53.