Dealing with the Devastation

How to provide oral health care to patients with a history of methamphetamine abuse.

This course was published in the December 2010 issue and expires December 2013. The authors have no commercial conflicts of interest to disclose. This 2 credit hour self-study activity is electronically mediated.

EDUCATIONAL OBJECTIVES

After reading this course, the participant should be able to:

- Discuss the systemic effects of methamphetamine abuse.

- Recognize the behavioral characteristics associated with methamphetamine abuse.

- Identify the oral symptoms that occur as a result of long-term methamphetamine abuse.

- Outline the preventive, restorative, and periodontal services that can be incorporated into the treatment plan for patients who are currently using or recovering from methamphetamine addiction.

- Explain the precautions that the dental clinician must take when treating a current or recovering methamphetamine user

Data from 2005 showed that young adults aged 18 to 25 years had the highest incidence of methamphetamine use. There is some hope. A 2008 survey found that the number of young people (aged 18 to 25 years) who had used methamphetamine in the past year had decreased significantly from 731,000 in 2005 to 314,000 in 2008.4

Slang terms for methamphetamine include ice, speed, fire, crank, chalk, crystal meth, yaba, tina, stove top, and poor man’s cocaine.1 Methamphetamine is distributed as a white, odorless powder with a bitter taste that dissolves in water and can be inhaled, smoked, swallowed, or injected.2,5

Methamphetamine use provides intense, long-lasting effects that include a prolonged feeling of joy and excitement, appetite suppression, increased energy, and heightened alertness. The effects of methamphetamine are felt within 15 minutes to 20 minutes when taken orally and in 3 minutes to 5 minutes when snorted.2,6

Smoking or injecting methamphetamine can be felt within 15 seconds and its effect is often described as an extreme rush, which is due to the release of high levels of dopamine within the brain.2,6,7

SYSTEMIC EFFECTS

The short-term effects of methamphetamine include sleeplessness, hyperactivity, decreased appetite, increased respiration, rapid/irregular heartbeat, high blood pressure, euphoria, nausea, vomiting, dilated pupils, and hyperthermia.2,6 Long-term use causes paranoia, anxiety, insomnia, depression, irritability, hallucinations, mood swings, violent behavior, and permanent brain damage.2,6,8 Users often develop skin lesions due to compulsive scratching and picking, which when left untreated, can develop into abscesses, cellulitis, and infection.9 Due to the appetite suppression effects of the drug, methamphetamine users are often underweight and malnourished. Chronic use of methamphetamine often leads to tolerance of the drug’s pleasurable effects and addiction.2

ORAL MANIFESTATIONS

The chief complaint of methamphetamine users is xerostomia.10,11 The drug activates alpha-adrenergic receptors within the vasculature of the salivary glands that cause vasoconstriction within the gland and a reduction of salivary flow.12,13 It also produces hyperactivity, which can cause excessive sweating.10,12 Methamphetamine users often drink large quantities of sugared, carbonated soft drinks instead of water to alleviate their xerostomia.10,14,15

Xerostomia, poor oral hygiene, vomiting, and increased intake of refined carbohydrates, sucrose, and carbonated beverages contribute to a high incidence of dental caries in methamphetamine users.12,15,16 They often have blackened, stained, and rotting dentition due to untreated caries.17 This condition is commonly referred to as “meth mouth.” Carious lesions in methamphetamine users typically occur on the buccal surface of posterior teeth and interproximal surfaces of anterior teeth.18-20 The decay is typically aggressive and tends to undermine the enamel, resulting in complete tooth destruction.18-20 Severely decayed teeth may need to be extracted. Even though the rate of decay appears rampant, it is different than the carious lesions seen in drug- or post-radiation-induced xerostomia. Methamphetamine-related caries is similar to caries seen in people with Sjögren’s syndrome, however, the decay process appears to go through periods of arrest.19

Explanations for this pattern are unclear, but some theorize that methamphetamine users brush their teeth when they are not high, thus altering the decay progression.19 Excessive tooth wear is also frequently observed in chronic methamphetamine users, who are often extremely active and exhibit excessive neuromuscular activity.21-23 During times of acute use and when coming off the drug, methamphetamine users tend to grind and clench their jaws. Snorting methamphetamine appears to cause excessive wear on the maxillary anterior teeth, while those who smoke, inject, or take the drug orally have more occlusal wear on the posterior teeth.22,23 Bruxism and chronic contraction of the muscles of mastication can also exacerbate existing periodontal diseases and can cause pain within the masseter muscle and temporomandibular joint (TMJ).11,21

CASE REPORT

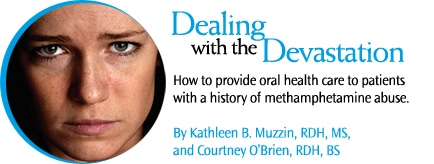

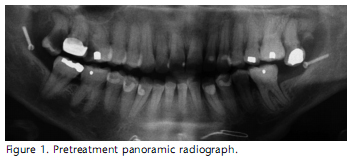

A 36-year-old Caucasian woman was referred to Baylor College of Dentistry with a complaint of profuse oral pain. The patient had a history of substance abuse and reported smoking methamphetamine and marijuana two to three times a day for 7 years. She had been drug-free for 4 years. The extraoral exam revealed an enlarged and slightly firm masseter muscle, and attrition on the posterior teeth. Her initial dental screening exam revealed that her entire dentition, specifically the cervical area on all the buccal surfaces, had enamel decalcification and pitting. Decay was found on tooth numbers 1 through 3, and 15, and tooth number 16 had a retained root tip (Figure 1). Periodontally, she exhibited generalized moderate diffuse erythema, edema, and bulbous papillary tissue (Figures 2 to 5). Pockets depths ranged from 1 mm to 5 mm with generalized bleeding on probing. Class 1 mobility was found on tooth numbers 4, 7, 8, 9, and 23 through 26, and moderate gingival recession was observed on the mandibular anterior teeth. In addition, tooth numbers 11 and 24 exhibited mucogingival defects. Radiographically, horizontal bone loss was apparent on the posterior teeth (Figure 1). Moderate to severe amounts of plaque and materia alba were present (48% plaque score), as were generalized heavy supragingival and subgingival calculus deposits.

The initial treatment plan called for extraction of tooth numbers 1 through 3, 15, and 16. The dental hygiene care plan included nonsurgical periodontal therapy, discussion about the etiology of caries and periodontal diseases, and instruction on Bass tooth brushing technique, flossing, and the use of an end-tuft toothbrush for the posterior teeth. A prescription-strength fluoride gel, a desensitizing toothpaste, and alcohol-free mouthrinse were also recommended. Periodontal debridement was completed in five appointments. One obstacle encountered during treatment was determining the difference between the patient’s enamel and calculus. The enamel surface was exceedingly soft and flaked off during instrumentation. The dental hygienist had a difficult time distinguishing whether chalky white areas on the enamel (when aair dried were either calculus or enamel. Therefore, it was crucial to discern when to stop scaling.

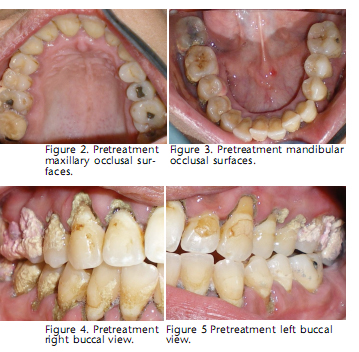

Re-evaluation of her periodontal condition 3 weeks later revealed significant improvement in the patient’s overall periodontal health (Figures 6 through 8). Pocket depth reduction ranged from 1 mm to 3 mm. There was absence of bleeding on probing and small amounts of residual calculus. Her plaque score was 17%. Remaining calculus from the previous appointments was removed, and the teeth were polished with a professional desensitizing agent that contained calcium carbonate and arginine. A 5% sodium fluoride varnish was also applied to the entire dentition.

PATIENT MANAGEMENT

Patients who report a history of methamphetamine use need to be questioned regarding the method of administration and any residual adverse systemic effects. Even if the patient is no longer using, systemic and psychological effects of substance abuse may still be present. Recovered methamphetamine users may experience depression, mood swings, psychosis, paranoia, and cardiovascular problems, which in turn can affect dental care plans.12,24

Medications taken by the patient should be recorded and any oral side effects should be documented. Not all former substance abusers will disclose their past drug use, however, clinicians should approach patients who are recovering from substance abuse in a nonjudgemental manner and demonstrate concern for their oral health care needs. Clinicians should also document any physical and/or behavioral characteristics that are associated with methamphetamine use. Lesions on the face and arm from compulsive skin picking are often seen on chronic drug users.25 Linear red lesions on the skin (skin tracks) are seen in individuals who inject methamphetamine20and users will often wear long sleeve shirts to cover the needle track marks.25

Behavioral signs of methamphetamine use include a disorderly appearance, erratic demeanor, rapid pacing, restlessness, and twitching.24 Some methamphetamine users exhibit psychotic symptoms and may become violent.6,20 Patients who make frequent requests for lost or stolen pain medication before their prescription refill date, demand a specific controlled analgesic for their dental pain, and report allergies to multiple pain medications are suspect for drug abuse.26

Once a patient is identified as having a substance abuse problem, the clinician should refer the patient to a physician or substance abuse counselor.19,26  Due to the unique pattern of dental caries seen in patients who use methamphetamine, the oral health care professional may be the first health care provider to identify a current or former methamphetamine user.20 In order to prevent further carious lesions, clinicians should evaluate the patient’s diet, assess for xerostomia, and stress the importance of good oral hygiene. Nutritional counseling regarding the intake of sugar containing food and beveragesshould be provided. 15

Due to the unique pattern of dental caries seen in patients who use methamphetamine, the oral health care professional may be the first health care provider to identify a current or former methamphetamine user.20 In order to prevent further carious lesions, clinicians should evaluate the patient’s diet, assess for xerostomia, and stress the importance of good oral hygiene. Nutritional counseling regarding the intake of sugar containing food and beveragesshould be provided. 15

Recommendations should include eating a balanced diet, incorporating cariostatic foods, avoiding food and beverages that contain large amounts of sugar, and discontinuing consumption of carbonated soft drinks.15

Oral moisturizers, such as saliva substitutes, and pharmacologic agents, such as pilocarpine or cevimeline HCL, should be recommended for xerostomia and patients should be encouraged to drink more water.9,10,19 Thorough plaque removal should be performed daily24 and preventive agents, such as prescription neutral sodium fluoride (mouthrinse, toothpaste, or gel), should be incorporated in patients’ daily regimens to prevent further decay. 10,14,15,20

Fluoride varnish should be applied to areas of decalcification.24 Products that contain calcium phosphate technologies can be used to remineralize cavitated areas and inhibit further lesion development.24

Chewing gum that contains sugar alcohols, such as xylitol and sorbitol, can also be included as an additional caries preventive agent. Fluoride-releasing restorative materials, such as glass ionomer cements and resinmodified glass ionomers, should be used to treat existing carious lesions.24

Periodontal care should include complete debridement, application of site-specific antimicrobial drugs, and rinsing with chemotherapeutic mouthrinses.24 Patients who exhibit signs of occlusal wear should be evaluated for bruxism. Treatment options, such as occlusal splints, can be recommended. Referral to a specialist may be needed if the patient reports TMJ discomfort. Managing pain may be difficult when providing dental treatment for recovered methamphetamine users. Many former users refuse to take mood-altering drugs, and clinicians should abstain from administering any medication that is similar in composition to methamphetamine.9 In addition, opioid analgesics should not be prescribed because their use can lead to a relapse.14,20 Instead, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs are recommended for pain management.9,10 Clinicians who suspect a patient is misusing methamphetamine should take additional precautions when providing dental care. Tolerance to sedative and anesthetic agents can occur so that larger doses are needed for pain control.9

Inhalative sedative agents, such as nitrous oxide, should be avoided.26 Abuse of methamphetamine can cause profound vasoconstriction that can lead to a hypertensive crisis, stroke, or heart attack.2,19 To prevent cardiovascular effects, clinicians should not use local anesthetics that contain a vasoconstrictor, such as epinephrine, for at least 24 hours after the patient’s last dose of methamphetamine. 10,14,20 Postponing dental treatment until methamphetamine abuse is controlled is a more prudent approach. If immediate dental care is needed, however, local anesthetics that do not contain epinephrine are appropriate alternatives.14 Even though local anesthetics that do not contain vasoconstrictors are considered safe to use on methamphetamine abusers, unforeseen cardiovascular events may occur, therefore, the patient’s vital signs should be monitored throughout the dental appointment.

Understanding the systemic effects and oral manifestations associated with methamphetamine use will assist clinicians in developing appropriate dental care plans for their patients. Reinforcement of the importance of oral hygiene and caries prevention and evaluation for restorative care should be provided at regular intervals in this patient population.

REFERENCES

- United States Drug Enforcement Administration. Drug Scheduling. Available at www.justice.gov/dea/pubs/scheduling.html. Accessed November 13, 2010.

- National Institute on Drug Abuse Research Report Series. Methamphetamine Abuse and Addiction. Available at: www.nida.nih.gov/ResearchReports/Methamph/Methamph.html. Accessed November 13, 2010.

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration Office of Applied Studies. Amphetamines/Methamphetamines. Available at: www.oas.samhsa.gov/amphetamines.htm. Accessed November 13, 2010.

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration Office of Applied Studies. Results from the 2008 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: National Findings. Available at: http://oas.samhsa.gov/nsduh/2k8nsduh/2k8Results.cfm. Accessed November 13, 2010.

- National Institute on Drug Abuse Research Report Series. NIDA InfoFacts: Methamphetamine. Available at http://drugabuse.gov/infofacts/methamphetamine.html. Accessed November 13, 2010.

- Lineberry TW, Bostwick JM. Methamphetamine abuse: a perfect storm of complications. Mayo Clin Proc. 2006;81:77-84.

- Cho AK, Melega WP. Patterns of methamphetamine abuse and their consequences. J Addict Dis. 2002;21:21-34.

- Volkow ND, Chang L, Wang GJ, et al. Association of dopamine transporter reduction with psychomotor impairment in methamphetamine abusers. Am J Psychiatry. 2001;158:377-382.

- Rhodus NL, Little JW. Methamphetamine abuse and “meth mouth.” Northwest Dent. 2005;84:29,31,33-37.

- Donaldson M, Goodchild JH. Oral health of the methamphetamine abuser. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2006;63:2078-2082.

- McGrath C, Chan B. Oral health sensations associated with illicit drug use. Brit Dent J. 2005;198:159-162.

- Saini TS, Edwards PC, Kimmes NS, Carroll LR, Shaner JW, Dowd FJ. Etiology of xerostomia and dental caries among methamphetamine abusers. Oral Health Prev Dent. 2005;3:189-195.

- Di Cugno F, Perec CJ, Tocci AA. Salivary secretion and dental caries in drug addicts. Archs Oral Biol. 1981;26:363-367.

- Goodchild JH, Donaldson M. Methamphetamine abuse and dentistry: a review of the literature and presentation of a clinical case. Quintessence Int. 2007;38:583-590.

- Shaner JW. Caries associated with methamphetamine abuse. J Mich Dent Assoc. 2002;84:42-47.

- Morio KA, Marshall TA, Qian F, Morgan TA. Comparing diet, oral hygiene and caries status of adult methamphetamine users and non-users. A pilot study. J Am Dent Assoc. 2008;139:171-176.

- American Dental Association. For the dental patient: methamphetamine use and oral health. J Am Dent Assoc. 2005;136:1491.

- Shaner JW, Kimmes N, Saini T, Edwards P. Case report “meth mouth:” rampant caries in methamphetamine abusers. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2006;20:146-150.

- Hamamoto DT, Rhodus NL. Methamphe?ta?mine abuse and dentistry. Oral Diseases. 2009;15:27-37.

- Klasser GD, Epstein JB. The methamphetamine epidemic and dentistry. Gen Dent. 2006;54:431-439.

- Shetty V, Mooney LJ, Zigler CM, Belin TR, Murphy D, Rawson R. The relationship between methamphetamine use and increased dental disease. J Am Dent Assoc. 2010;141:307-318.

- Richards JR, Brofeldt BT. Patterns of tooth wear associated with methamphetamine use. J Periodontol. 2000;71:1371-1374.

- Redfearn PJ, Agrawal N, Mair LH. An association between the regular use of 3, 4 methylenedioxy-methamphetamine (Ecstasy) and excessive wear of the teeth. Addiction. 1998;93:745-748.

- Kelsch NB. Methamphetamine abuse—oral implications and care. RDH. 2009;29(2):85-93.

- Scofield JC. The gravity of methamphetamine addiction. Dimensions of Dental Hygiene. 2007;5(3):16-18.

- Curtis EK. Meth mouth: a review of methamphetamine abuse and its oral manifestations. Gen Dent. 2006;54:125-129.

From Dimensions of Dental Hygiene. December 2010; 8(12): 42-45.