Strategies for Detection and Intervention

How to recognize and treat patients with anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa in the dental setting.

This course was published in the December 2010 issue and expires December 2013. The authors have no commercial conflicts of interest to disclose. This 2 credit hour self-study activity is electronically mediated.

EDUCATIONAL OBJECTIVES

After reading this course, the participant should be able to:

- Define anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa.

- List the most common health problems associated with each disorder.

- Explain the oral complications of each disorder.

- Discuss the dental professional’s role in identification and intervention of anorexia and bulimia

Bulimia nervosa is characterized by recurrent unrestrained eating sprees followed by purging or fasting. Binges are often associated with an intense emotional experience, such as rejection, depression, or stress followed by a strong feeling of guilt.7 Thereis considerable overlap between anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa.8 People with anorexia may also have episodes of binge eating and vomiting, and those with bulimia may also have periods of severe food restriction. In the past, those affected by eating disorders were often from middle to high socioeconomic backgrounds, however, over the past 20 years eating disorders have become equally widespread among all socioeconomic classes.9,10 A family history of psychoneuroses, particularly depression, schizophrenia, obsessive-compulsive personalities, and alcoholism, is common among patients with eating disorders.

People at risk of eating disorders often have difficulty with self-regulation, poor self-esteem, and insecure attachment. Diet becomes the instrument through which people attempt to control and manipulate their problems. 11 In spite of increased awareness and expanded media exposure, a specific etiology for the pathogenesis of anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa remains elusive. The cause of the disorders is believed to be multifactorial and research has focused on environmental and social factors, biological vulnerability, and psychological and genetic predisposition. 12 The incidence of eating disorders among boys and men has risen over the past few decades. 13,14 Boys and men involved in occupations or sports in which weight control is related to performance, such as bodybuilding, cheerleading, dancing, distance running, diving, figure skating, gymnastics, horse racing, rowing, swimming, and wrestling, are at greater risk of eating disorders. 15,16

ANOREXIA NERVOSA

Anorexia nervosa is a serious illness that can be life-threatening. The onset of anorexia is most common at 13 to 14 years and 17 to 18 years of age. 17 Anorexia nervosa has the highest rate of mortality among all mental disorders. 18 Anorexia nervosa has biological, psychological, and sociocultural components. Society’s emphasis on thinness as a criterion for beauty puts predisposed individuals at risk.

The exaggerated goal of thinness leads to significant weight loss where individuals fall below the minimal normal weight for their age and height. Low body weight is the result of severe and selective food restriction, excessive exercise, and/or use of purgatives and laxatives. An impaired sense of personal identity, perceptual disturbances, childhood obesity, family history of eating disorders, rigid relationships with over-protective parents that discourage adolescent autonomy, a perfectionist personality, cognitive disturbances, and neuroendocrine vulnerability all may be predisposing factors. 19-21

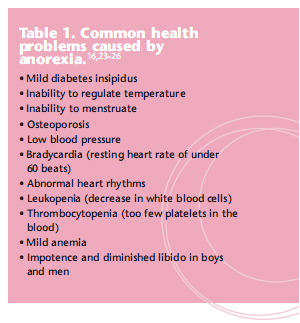

Approximately 0.5% to 1% of adolescent girls and adult women meet the American Psychiatric Association (APA) diagnostic criteria for anorexia nervosa. 7,9,17,22 These criteria include: a refusal to maintain body weight above a minimal normal weight for age and height; a morbid fear of gaining weight or becoming obese; perceptual disturbance regarding body weight, size, or shape; and a ceasing of the menstrual cycle. There are numerous medical complications associated with anorexia nervosa that involve almost all organ systems. Metabolic, cardiovascular, and endocrine disturbances are caused by self-induced starvation and malnutrition. Table 1 lists the most common health problems experienced by people with anorexia. 16,23-26 Fortunately, the metabolic disturbances and physical changes are usually reversible with weight gain and adequate nutritional intake. But the risk of relapse and premature death is high even with professional intervention. 27

BULIMIA NERVOSA

The etiology of bulimia nervosa is unknown but it appears to be complex with individual, family, sociocultural, and iatrogenic factors. Bulimia has typical onset of 17 to 25 years of age with a range of 13 to 35 years of age. 28 Patients with bulimia often have outgoing personalities and exhibit compulsive behaviors. The disorder is characterized by a distorted body image and an intense preoccupation with food and weight, coupled with a morbid fear of becoming obese. The consumption of large quantities of food (binge), usually at night, is common. Frequently following the binge, the individual is overcome with feelings of guilt and shame for losing self-control, which results in purging (emesis) of the gastric contents.

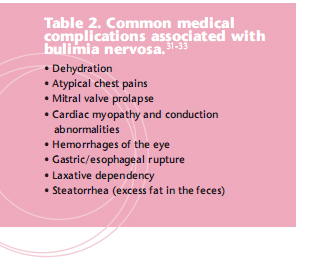

The goal of an individual with bulimia nervosa is to eat and not gain weight in contrast to the person with anorexia nervosa who only desires to lose weight. People who primarily practice bingepurge type behavior are often of normal or near normal weight and may never show signs of serious medical problems. 29 Unlike anorexia nervosa, which is much more common among white women, bulimia nervosa and binge-eating also occur frequently among black women. 29 Personality characteristics of depression, anxiety, over concern with food, distorted body perception, feelings of inadequacy, and helplessness may predispose an individual to bulimia nervosa. 30 APA diagnostic criteria for bulimia nervosa include: repeated episodes of binge eating; a feeling of losing control over eating during binges; regularly engaging in self-induced regurgitation of consumed food; abusing laxative and diuretics; practicing strict dieting or vigorous exercise in order to prevent weight gain; and a persistent concern with body shape and weight. 7 Table 2 (page 44) lists the more common medical complications associated with bulimia nervosa. 31-33

ORAL COMPLICATIONS![]()

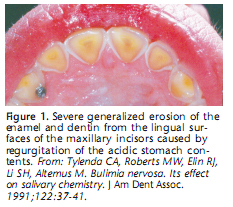

The cariogenicity of the diet and the duration and frequency of binge-purge behavior are the primary variables that impact the oral complications associated with anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa. The individual practicing binge-purge behavior usually prefers high caloric, sugar-containing foods that can be easily swallowed. Erosion of the teeth is common if the practice of regurgitating the highly acidic gastric contents is long standing (it takes 2 years to 3 years to become clinically apparent). Dental erosion affects 20% of individuals with anorexia nervosa and more than 90% of patients with bulimia nervosa. 34 The lingual and incisal/ oc clusal enamel surfaces of the maxillary incisors and premolars are affected first (Figure 1). Aggressive oral cleaning with a hard bristle toothbrush, especially immediately after regurgitation, can increase the loss of dental enamel.

The occlusal surfaces of the mandibular premolars and molars may also be affected but not as frequently as those in the maxilla. This is due to the protection afforded by the tongue, close contact with the mucous membranes of the cheeks, and the buffering effects of pooled saliva. 34 Some individuals with eating disorders seem to experience a higher risk of dental caries while others do not. 35-37 This may be caused by differences in oral hygiene, cariogenicity of the diet, genetic predisposition, fluoride contact during the tooth-forming years, and saliva flow. People who practice binge-purge behavior often experience painless enlargement of the parotid gland and, occasionally, the submandibular salivary glands. These enlargements can occur unilaterally or bilaterally (Figure 2). 38,39 The etiology of this enlargement has not been definitively established. 40,41 The gland enlargements are usually self-limiting and they regress spontaneously over time when the binge-purge behavior is discontinued.

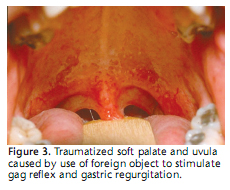

Xerostomia is often seen in patients who have eating disorders. The loss of moisture and the protective qualities of saliva can result in dehydration of the soft tissues and be exaggerated by dietary vitamin and protein deficiencies. Angular cheilosis and necrotizing ulcerative gingivitis-like inflammation with ulceration and gingival bleeding may result. 42 Vitamin B deficiency is associated with a sore or burning tongue and can occur throughout the entire mouth. 43 Trauma-induced pharyngeal tears and erythema of the palate, pharynx, and posterior tongue can result from the use of fingers or other objects to induce gagging and the regurgitation of the stomach contents (Figure 3). The low pH of the vomitus can cause additional damage to the soft tissues. 44

IDENTIFICATION AND INTERVENTION![]()

Dental professionals can play a pivotal role in the identification and intervention of eating disorders because they may be the first health professionals to witness the early symptoms. Addressing patients who exhibit eating disorder symptoms can be difficult. The topic needs to be broached with sensitivity and without the labels of “eating disorder,” “anorexia,” or “bulimia.”45 A referral to the patient’s primary care physician or to a health professional who specializes in treating eating disorders is the most prudent course of action. 45,46 The dental professional should remain part of the multidisciplinary team that is addressing the eating disorder. 47,48

Patients can also be advised about how to limit damage of the oral cavity. The mouth must be rinsed after each purge but toothbrushing should be delayed for a few hours. The delay in brushing will permit partial tooth remineralization and prevent the additional loss of damaged enamel rods. Rinsing with a solution of water and sodium bicarbonate immediately after purging episodes will help neutralize the vomited gastric contents. 49 The daily use of a neutral sodium fluoride mouthrinse or the application of a neutral sodium fluoride gel in custom trays, in addition to the use of a fluoride-containing toothpaste can be helpful in reducing the loss of dental enamel. 50 The customary twice-a-day brushing of teeth and daily flossing should be encouraged to maintain periodontal health. 51 Chewing a sugar-free gum can often help relieve the symptoms of xerostomia.

With continued societal emphasis on excessive thinness as a desirable goal, eating disorders will most likely remain prevalent, particularly among young people. Eating disorders can have dire consequences. Among people with all types of eating disorders, 20% will die prematurely from complications related to their disorder. 18 Early diagnosis and intervention are the keys to successful treatment and recovery. Dental professionals can make a difference in the overall health of their patients by acting when patients first present with symptoms of these devastating disorders.

REFERENCES

- Nicholis D, Viner R. Eating disorders and weight problems. Br Med J. 2005;330:950-953.

- Herzog DB, Copeland PM. Eating disorders. N Engl J Med. 1985;313:295-303.

- Tenore JL. Challenges in eating disorders: past and present. Am Fam Physician. 2001;64:367.

- Currin L, Schmidt U, Trassue J, Jick H. Time trends in eating disorder incidence. Br J Psychi?a?try. 2005;186:132-135.

- Pritts SD, Susman J. Diagnosis of eating disorders in primary care. Am Fam Physician. 2003;67:297-304.

- Casper RC, Eckert ED, Halmi KA. Bulimia: Its incidence and clinical importance in patients with anorexia nervosa. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1980;37:1030-1035.

- Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders-DSM-IV-TR. 4th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2000:583-597.

- Woodside BD, Staab R. Management of psychiatric comorbidity in anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa. CNS Drugs. 2006;20:655-663.

- Hsu LK. Epidemiology of the eating disorders. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 1996;19:681-700.

- Emans SJ. Eating disorders in adolescent girls. Pediatr Int. 2000;42:1-7.

- Lo Russo L, Campisi G, Di Fede O, Di Liberto C, Panzarella V, Lo Muzio L. Oral manifestations of eating disorders: a critical review. Oral Dis. 2008;14:479-484.

- Garner DM. Pathogenesis of anorexia nervosa. Lancet. 1993;341:1631-1635.

- Anderson EA. Anorexia nervosa and bulimia in adolescent males. Pediatr Ann. 1984;13:901-907.

- Crisp AH, Burns T, Bhat AV. Primary anorexia nervosa in the male and female: A comparison of clinical features and prognosis. Br J Med Psychol. 1986;59:123-132.

- Committee on Sports Medicine Fitness. Promotion of health weight-control practices in young athletes. Pediatrics. 1996:97:752-753.

- Glazer JL. Eating disorders among male athletes. Curr Sports Med Rep. 2008;7:332-337.

- Hobbs WL, Johnson CA. Anorexia nervosa: an overview. Am Fam Physician. 1996;54:1273-1279,1284-1286.

- Harris EC, Barrachough B. Excess mortality of mental disorders. Br J Psychiatry. 1998;173:11-53.

- Garner DM, Garfinkel PE, Olmstead MP. An overview of society cultural factors in the development of anorexia nervosa. In: Darby PL, Garfinkel PE, Garner DM, et al eds. Anorexia Nervosa: Recent Developments in Research. New York: Liss; 1983:3-14.

- Gelbaugh S, Ramos M, Soucar E, Urena R. Therapy for anorexia nervosa. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2001;40:129-130.

- Garfinkel PE, Garner DM. The role of the family. In Garfinkel PE, Garner DM, eds. Anorexia Nervosa: A Multidimensional Perspective. New York: Brunner-Mazel; 1982:164-187.

- Pope HG, Hudson JI, Yurgelun-Todd D, Hudson MS. Prevalence of anorexia nervosa and bulimia in three student populations. Int J Eat Disord. 1984;3:45-51.

- Miller CA, Golden NH. An introduction to eating disorders: clinical presentation, epidemiology, and prognosis. Nutr Clin Pract. 2010;25:110-115.

- Gottdiener JS, Gross HA, Henry WL, Borer JS, Ebert MH. Effects of self induced starvation on cardiac size and function in anorexia nervosa. Circulation. 1978;58:425-433.

- Thurston J, Marks P. Electrocardiographic abnormalities in patients with anorexia nervosa. Br Heart J. 1974;36:719-723.

- Palmblad J, Fohlin L, Lundstrom M. Anorexia nervosa and polymorphonuclear (PMD) granu?lo?cyte reactions. Scand J Haematol. 1977;19:344-342.

- Norring CEA, Sohlberg SS. Outcome, recovery, relapse and mortality across 6 years in patients with clinical eating disorders. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1993;87:437-444.

- Favaro A, Caregaro L, Tenconi E, Bosello R, Santonastaso P. Time trends in age at onset of anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa. J Clin Psychiatry. 2009;70:1715-1721.

- Striegel-Moore RH, Dohm FA, Kraemer HC, et al. Eating disorders in white and black women. Am J Psychiatry. 2003;160:1326-1331.

- Johnson C. Initial consultation for patients with bulimia and anorexia nervosa. In: Garner DM, Garfinkel PE, eds. Handbook of Psycho?therapy for Anorexia Nervosa and Bulimia. New York: Guilford press; 1984:19-51.

- Johnson GL, Humphries LL, Shirley PB, Mazzoleni A, Noonan JA. Mitral valve prolapsed in patients with anorexia nervosa and bulimia. Arch Intern Med. 1986;146:1525-1529.

- Saul SH, Kekker A, Watson CG. Acute gastric dilation with infarction and performation: Report of fatal outcome in patient with anorexia nervosa. Gut. 1981;22:978-983.

- Roerig JL, Steffen KJ, Mitchell JE, Zunker C. Laxative abuse: epidemiology, diagnosis and management. Drugs. 2010;70:1487-1503.

- Bassiouny MA, Pollack RL. Esthetic management of perimolysis with porcelain laminate veneers. J Am Dent Assoc. 1987;115:412-417.

- Little JW. Eating disorders: dental implications. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2002;93:138-143.

- Öhrn R, Enzell K, Angmar-Mansson B. Oral status of 81 subjects with eating disorders. Eur J Oral Sci. 1999;107:157-163.

- Roberts MW, Li S-H. Oral findings in anorexia and bulimia nervosa: A study of 47 cases. J Am Dent Assoc. 1987;115:407-410.

- Mignogna MD, Fedele S, Lo Russo L. Anorexia/bulimia-related sialadenosis of palatal minor salivary glands. J Oral Pathol Med. 2004;33:441-442.

- Katsilambros L. Asymptomatic enlargement of the parotid glands. JAMA. 1961;178:513-514.

- Levin PA, Falko JM, Dixon K, Gallup EM, Saunders W. Benign parotid enlargement in bulimia. Ann Intern Med. 1980;93:827-829.

- Brady JP. Parotid enlargement in bulimia. J Fam Pract. 1985;20:496-502.

- Christensen GJ. Oral care for patients with bulimia. J Am Dent Assoc. 2002;133:1689-1691.

- Lamey P-J, Lamb AB. Prospective study of aetiological factors in burning mouth syndrome. Br Med J. 1988;296:1243-1246.

- Carni JD. The teeth may tell: Dealing with eating disorders in the dentist’s office. J Mass Dent Soc. 1981;30:80-86.

- Bishop ER Jr. Innate temperament and eating disorder treatment. Addiction Professional. 2010;8(3):14-19.

- Hague AL. Eating disorders screening in the dental office. J Am Dent Assoc. 2010;141:675-678.

- Hazelton LR, Faine MP. Diagnosis and dental management of eating disorder patients. Int J Prosthodont. 1996;9:65-73.

- Burkhart N, Roberts M, Alexander M, Dodds A. Communicating effectively with patients suspected of having bulimia nervosa. J Am Dent Assoc. 2005;136;1130-1137.

- Wolcott RB, Yager J, Gordon G. Dental sequel to the binge-purge syndrome (bulimia): Report of cases. J Am Dent Assoc. 1984;109:723-725.

- Lazarchik DA, Filer SJ. Effects of gastroesophageal reflux on the oral cavity. Am J Med. 1997;103:107S-113S.

- Clark DC. Oral complications of anorexia nervosa and/or bulimia: With a review of the literature. J Oral Med. 1985;40:134-138.

From Dimensions of Dental Hygiene. December 2010; 8(12): 38-41.