BERT_PHANTANA/ISTOCK/GETTY IMAGES PLUS

BERT_PHANTANA/ISTOCK/GETTY IMAGES PLUS

Ergonomics Reinvigorated

Strategies for using the Core Four to help prevent musculoskeletal disorders.

This course was published in the January 2019 issue and expires January 2022. The authors have no commercial conflicts of interest to disclose. This 2 credit hour self-study activity is electronically mediated.

EDUCATIONAL OBJECTIVES

After reading this course, the participant should be able to:

- Discuss the prevalence of musculoskeletal disorders (MSDs) in oral health professionals.

- Identify barriers to implementing an effective exercise program designed to reduce the risk of MSDs.

- Describe the four elements of the Core Four method.

It should come as no surprise that ergonomics is a noteworthy topic within the professions of dentistry and dental hygiene. As is well established, oral health professionals are at a remarkably high risk of experiencing a physical injury while performing their normal work duties.1 In fact, dental hygienists frequently seek out remedial care to address persistent musculoskeletal disorders (MSDs), with estimates indicating that 60% to 96% of the workforce are impacted.2 MSDs most commonly affect the neck, shoulders, wrist, and hand in the dental population.3,4 Despite avid attempts to educate dental professionals and implement ergonomic-based programs, MSDs are increasingly prevalent among this population.

The tasks involved with dental hygiene labor are associated with MSDs due to the normal array of physical demands that are inherent to the occupation. These include prolonged sitting, leaning forward to provide patient care, repetitive pinching and grasping, operating equipment, and routine computer work.5 In addition to these factors, many dental hygienists face uninterrupted work cycles, leaving clinicians with few opportunities to implement structured rest breaks. These occupational dynamics illustrate why the proper establishment and maintenance of a routine movement program can help to reverse the effects of this rigorous type of work.

COMMON BARRIERS TO IMPLEMENTING A MOVEMENT PROGRAM

One of the most common barriers to implementing an ergonomic-based exercise plan is a persistent lack of time. In fact, health care workers frequently neglect their own self-care as a result of the heavy burden of caring for others.6 Other common factors that limit performance include a lack of supervisory support, inadequate physical space, improper education, reduced self-efficacy, financial barriers, or working in a clinic culture where ergonomics is not highly valued.7–10 Whether one or more of these obstacles exist in any given workplace, a great deal of individual diligence and self-advocacy are required to adequately address this enduring dilemma.

In light of these identified barriers, it seemed necessary to develop an enhanced, more realistic model for ergonomic implementation among the dental hygiene population. With the support of Pacific University’s administration and the commitment of several dedicated students, the concept of the Core Four—a set of four activities that were explicitly designed after extensive movement analysis of dental hygienists in their work environment-—was developed. The program was designed to integrate the management of time, focus of a routine, and the necessary parameters for genuine tissue healing.

ORIGINS OF THE CORE FOUR

The Core Four is not entirely comprehensive; no four activities could ever fully inhibit the onset of an MSD. Instead, these four activities seek to reverse the normal effects of routine dental hygiene work on the most impacted tissues of the human body.3,4 Most significantly, these exercises should be viewed as corrective in nature for the targeted body areas, rather than as strictly preventive. Certainly, the consistent performance of these activities may directly alleviate the potential for the onset of an MSD; however, these four activities primarily serve to disengage and correct the inherent stress created on clinicians’ joints, muscles, and tendons in the neck, shoulders, wrists, and hands so that their function can be restored for future demand.

The Core Four consists of two stretches and two movements, and each one is to be completed in a separate 1-minute interval. With the 4 individual minutes involved in the activities paired with the brief transition periods needed to obtain each of the desired body positions, the entire set should not require any longer than a total of 5 minutes to complete. Ideally, this set would be performed between every patient visit as part of a routine rest break regimen, and it should subsequently be adopted as a structured daily habit. However, some authors have suggested that microbreaks as short as 30 seconds throughout the day may be beneficial in reducing the onset of MSDs for workers who perform repetitive tasks.11

Taking breaks throughout the work day can also reduce the need for physical recovery at the end of the day and may positively influence the correlation of MSD occurrence.12,13 Throughout performance, normal breathing patterns should be maintained during each activity. Dental hygienists must be mindful of the tendency to hold their breath and strictly avoid this response.

IMPORTANCE OF STRETCHING

The stretches are a truly vital aspect of the program, as they seek to elongate those muscles that impact pinch, grip, and reach use during instrument-related activities. Muscles are contractile tissues, and they frequently shorten as dental hygienists perform normal tasks with their hands and wrists. After persistent, repeated contractions that shorten these muscles, it is necessary to re-establish the normal resting length of muscles so that their function can be re-optimized. Several noteworthy publications have consistently suggested over time that muscular stretches should be held for sustained 30-second increments in order to facilitate lasting tissue elongation;14–17 any quantity shorter than that may not achieve the desired effect.

Literature of a similarly robust nature reiterates that no additional benefit may be achieved after a duration of 60 seconds or longer. Therefore, each of the stretches specifically includes parameters that fulfill this evidence-based criteria.

Pertaining to the two movement activities, both are relevant to postural correction through the realignment of the natural curves of the spine. The spine has four normal curves to its anatomical shape, so “sitting up straight” is not a sensible option for the human body. Instead, individuals can develop a more keen awareness of the tendency toward postural malalignment and make intentional efforts to restore the natural curvature of the spine. This will reduce unnecessary stress on the spine. Both of the movement activities should be performed without overexertion or laborious effort and should instead be fulfilled in a fluid, gentle, and deliberate manner.

ELEMENT ONE

The first element of the Core Four is an extension-based stretch of the wrist and fingers that is commonly referred to as the “prayer stretch” (Figure 1). This activity seeks to elongate the flexor digitorum superficialis, flexor digitorum profondus, and flexor pollicis longus muscles, and can be performed in a seated or standing position.17

In order to perform it properly, place all five fingertips together and touch the palms firm in contact with one another starting at chest height very near to the trunk. Then, while maintaining close contact of the palms and fingertips, slowly lower the hands toward the waist until a mild but comfortable stretch is noted; most people will feel tension develop just above their wrist on the anterior (palm) side of their forearm. When this position does not yield a feeling of tension, the position of the hands can be maintained and the forearms can be rotated outward so that the fingers point directly away from the chest; this should enhance the feeling of stretch during performance.

of the wrist and fingers that is commonly referred to as the “prayer stretch.”

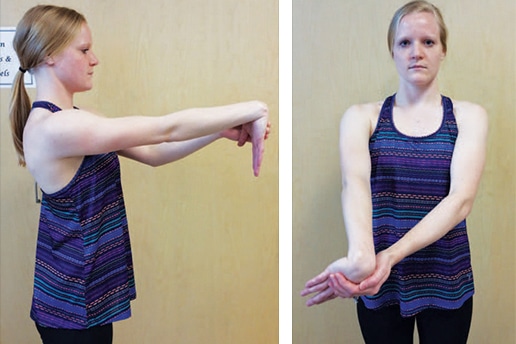

ELEMENT TWO

The second portion of the Core Four is a stretch that targets the extensor muscles located on the dorsal (backside) of the wrist and forearm (Figure 2). This seeks to elongate the extensor carpi radialis longus, extensor carpi radialis brevis, and extensor carpi ulnar muscles, and is normally completed by the dominant arm that operates clinical instruments during patient care; the contralateral extremity can receive a similar stretch if time allows.17 As part of proper performance, the elbow should be fully extended without being locked out or hyperextended, and the wrist should be flexed downward toward the palm side of the hand. The shoulder position can vary. The exercise can be done at shoulder height or below this location. Obtaining a point of personal comfort is the highest determination for this aspect of the stretch. Additionally, the contralateral hand (nonstretched side) should facilitate the stretch over the metacarpalphalangeal joints (largest knuckles on the back of the hand) and not over the fingers, as including finger flexion will target undesired muscles during performance.

If performed correctly, a stretch should be felt just proximal to the wrist in the posterior forearm. When this initial position no longer yields a feeling of tension, the shoulder can be rotated inward (causing the fingers to move relatively outward) while maintaining the same position of the elbow, wrist, and hand, so that further elongation can be achieved.

extensor muscles located on the dorsal (backside) of the wrist and forearm.

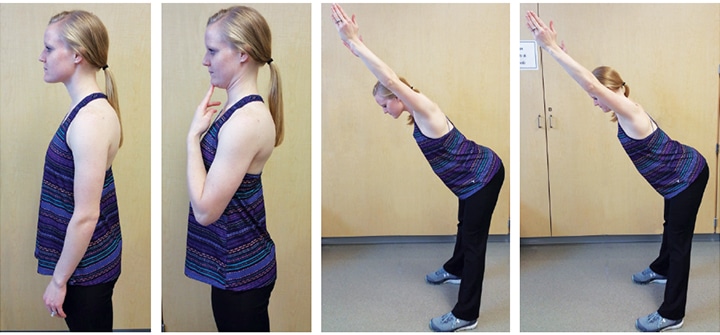

ELEMENT THREE

The third activity associated with the Core Four is a movement frequently called “tracing a doorframe”(Figure 3). Instead of facilitating a stretch of muscular tissue, this movement seeks to restore the normal alignment of the thoracic spine, facilitate scapular retraction, and activate some of our focal postural muscles. Normally, the thoracic spine (better known as the mid-back) is aligned in a kyphotic shape, where it curves away from the trunk to create a rounded shape. Slouching can exaggerate this curve and may cause added stress to the individual joints in this region of the spine. As dental hygienists tend to lean forward to interact with their patients—causing an excess of kyphosis in the thoracic spine—the initial reaching upward with both arms seeks to reverse this biomechanical shortcoming. Then, as the hands are drawn outward and then downward in the shape of a doorframe, the scapulae are drawn inward and downward into a more optimal position. This collective movement activates the lower trapezius, latissimus dorsi, and rhomboid major and minor, which helps to maintain the scapulae and shoulders in their desired, natural position.18 When this activity becomes effortless and fluid, an appropriate progression includes a gentle pinching of the scapulae together at the very end of the movement to further engage the postural muscles. This should not be overexerted, or a strain of the muscles between the scapulae can occur.

ELEMENT FOUR

The final activity from the Core Four is well-known as a “chin tuck” movement (Figure 4). Instead of seeking to correct the thoracic spine, this movement attempts to realign the cervical spine (neck region). The cervical spine has a normal curve that is in the reverse position of the thoracic spine beneath it, rounding to create a forward sway in its natural shape. Again, with the tendency to frequently look downward for prolonged periods in order to examine the mouths of patients, this lordotic curve can be exaggerated to the point where added stress is created in the neck through the added effect of gravity. This can be reduced significantly with the routine use of dental loupes.

In order to perform the chin-tuck movement properly, the head should be drawn backward to reduce the curve of the neck in either an upright seated or standing position. For some, it is helpful to cue proper performance by sharing the prompt to “create a double chin” by using their head and neck to draw the chin straight backward (posteriorly). This activity should create a feeling of tension in the anterior aspect of the neck where the deep neck flexors lie, but may also generate a sensation of stretch in the posterior neck from supporting muscles that have become short and tight. When this activity no longer creates adequate demand on the muscles that support the alignment of the neck, the chin tuck can be performed after leaning forward slightly through the hips while keeping the knees and back relatively straight. This position introduces supplemental resistance, as the muscles must engage against the added weight caused by moving against gravity.

CREATING ROUTINE

Overall, a decision to perform the Core Four is not incredibly noteworthy; rather, adopting this practice as a habitual routine poses a more daunting issue. Early models of habit formation indicate that nearly 6 months of consistent behavioral performance is required in order for the average person to establish a pattern as a lasting routine.19 Newer models indicate similar findings.20 Not coincidentally, if dental hygienists expect their patients to overcome the barriers of habit formation in order to perform daily oral hygiene during the extended span between recare visits, clinicians must expect nothing less of themselves. There is no denying that ergonomic implementation and maintenance are as equally important to our personal well-being.

Accountability is integral to the process of habit formation. Studies have long demonstrated the potential advantages of performing routine activities cooperatively as a means to achieve greater adherence.21 Not surprisingly, when a colleague, peer, or teammate endure the same processes with a similarly invested commitment, the likelihood of establishing a maintained routine greatly increases.

CONCLUSION

Despite the multitude of factors—both intrinsic and extrinsic—that create barriers to ergonomic adoption in the workplace, clinicians must uphold a genuine self-driven effort rooted in resolve so that the impact of MSDs is minimized. The Core Four routine seeks to introduce a corrective activity that reverses the effects of tissue stress specifically experienced by dental hygienists, and is designed for daily performance as part of a structured rest break regimen. As such, the collective effort to maintain ergonomics as a fundamental occupational priority will allow the disturbing trends in MSDs to greatly subside in the future. If normal work duties or the performance of the Core Four causes symptoms lasting greater than 72 hours, individuals should consult with a qualified medical provider to have their condition more formally evaluated.

REFERENCES

- Johnson CR, Kanji Z. The impact of occupation-related musculoskeletal disorders on dental hygienists. Canadian Journal of Dental Hygiene. 2016;50:72–79.

- Michalak-Turcotte C. Controlling dental hygiene work-related musculoskeletal disorders: the ergonomic process. J Dent Hyg. 2000;74:41–48.

- Morse T, Bruneau H, Dussetschleger J. Musculoskeletal disorders of the neck and shoulder in the dental professions. Work. 2008;35:419–429.

- Kumar SP, Kumar V, Baliga M. Work-related musculoskeletal disorders among dental professionals: An evidence-based update. Indian Journal of Dental Education. 2012;5(1):5–12.

- Hayes MJ, Cockrell D, Smith DR. A systematic review of musculoskeletal disorders among dental professionals. Int J Dent Hyg. 2009;7:159–165.

- Skovholt TM. The Resilient Practitioner: Burnout Prevention and Self-Care Strategies for Counselors, Therapists, Teachers, and Health Professionals. Boston: Allyn and Bacon; 2016.

- Crawford L, Gutierrez G, Harber P. Work environment and occupational health of dental hygienists: a qualitative assessment. J Occup Environ Med. 2005;47:623–632.

- Ross A. Human factors and ergonomics for the dental profession. Dent Update. 2016;43:688–90, 692–695.

- Droeze EH, Jonsson H. Evaluation of ergonomic interventions to reduce musculoskeletal disorders of dentists in the Netherlands. Work. 2005;25:211–220.

- Whysall ZJ, Haslam RA, Haslam C. Processes, barriers, and outcomes described by ergonomics consul- tants in preventing work-related musculoskeletal disorders. Appl Ergon. 2004;35:343–351.

- McLean L, Tingley M, Scott R, Rickards J. Computer terminal work and the benefits of microbreaks. Appl Ergon. 2001;32:225–237.

- Alexopoulos E, Stathi IC, Charizani F. Prevalence of musculoskeletal disorders in dentists. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2004;5:16.

- Bhandari SB, Bhandari R, Uppal RS, Grover D. Musculoskeletal disorders in clinical dentistry and their prevention. J Orofac Res. 2013;3:106–114.

- Micheo W, Baerga L, Miranda G. Basic principles regarding strength, flexibility, and stability exercises. PM R. 2012;4:805–811.

- Page P. Current concepts in muscle stretching. Int J Sports Phys Ther. 2012;7:109–119.

- Bandy WD, Irion JM. The effect of time on static stretch on the flexibility of the hamstring muscles. Phys Ther. 1994;74:845–50.

- Aminger P. Martyn M. Stretching for Functional Flexibility. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2010.

- Kebaetse M, McClure P, Pratt NA. Thoracic position effect on shoulder range of motion, strength, and three-dimensional scapular kinematics. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1999;80:945–950.

- Prochaska J, Velicer WF. The transtheoretical model of health behavior change. Am J Health Promot. 1997;12:38–48.

- Joseph RP, Daniel CL, Thind H, Benitez TJ, Pekmezi D. Applying psychological theories to promote long-term maintenance of health behaviors. Am J Lifestyle Med. 2016;10:356–368.

- Latkin CA, Knowlton AR. Social network assessments and interventions for health behavior change: a critical review. Behav Med. 2015;41:90–97.

From Dimensions of Dental Hygiene. January 2019;17(1):36–39.

Would love to see an article on condition of hygienists that have quit practicing due to degenerative conditions/chronic pain. Did they recover? Do they have residual pain and or new medical conditions from years of inflammation?

[…] small adjustments like these can help clinicians break those bad habits over time. Implementing the Core Four, exercises, pursuing complementary therapies, and applying ergonomic practices can also be helpful […]