MARILYN NIEVES/E+/GETTY IMAGES

MARILYN NIEVES/E+/GETTY IMAGES

Community Water Fluoridation

Oral health professionals need to be prepared to effectively educate patients regarding the benefits of this public health effort to prevent caries.

This year marks the 73rd anniversary of community water fluoridation in the United States.1 During this time, water fluoridation has been recognized as one of the greatest public health achievements.2 In 1945, water fluoridation was first established in Grand Rapids, Michigan, in an effort to reduce the high rate of dental caries that was common among the majority of Americans.1 Today, the number of communities with access to fluoridated water continues to expand, benefitting millions in the US.3 Current data show that approximately 75% of the US population live in areas with fluoridated public water systems.4 One of the Healthy People 2020 objectives is to increase the percentage of communities with water fluoridation to 80%.5 On an annual basis, it is estimated that at least 90 communities consider starting or discontinuing water fluoridation.2 Despite the strong evidence supporting community water fluoridation, oral health professionals often hesitate to advocate for it with their patients. This may be due to a lack of understanding about the topic or fear of patients’ opposing viewpoints. The aim of this discussion is to inform oral health professionals about community water fluoridation, including its benefits and the perceived controversy. Moreover, the intent is to support the role of oral health professionals in advocating for community water fluoridation.

BASICS OF WATER FLUORIDATION

Fluoride is a mineral that is naturally found in the environment, typically in very low quantities.6 The term community water fluoridation is used when an optimal amount of fluoride is adjusted in a public water supply for dental caries prevention.7 Current guidelines recommend community water systems use concentrations of fluoride at 0.7 milligrams/liter (mg/L) in drinking water to protect against caries and reduce the risk of dental fluorosis.8 This concentration is based on the latest evidence, and was updated from the 1962 recommendation of 0.7 mg/L to 1.2 mg/L.8 These guidelines assist communities and public water systems in determining the accurate amount of fluoride needed to prevent dental caries. Additionally, as fluoride is naturally occurring, some public water systems remove fluoride from the water supply to the 0.7 mg/L optimal level, in an effort to promote oral health, while also reducing the risk of dental fluorosis.8

Dental fluorosis is when the appearance of the tooth enamel is changed due to regular exposure to high concentrations of fluoride from infancy to age 8.9 Most cases of dental fluorosis in the US are mild.9 Mild dental fluorosis is an appearance of slightly visible white spots on the enamel, and in no way affects the function of the teeth.9 Mild dental fluorosis can be prevented via parents monitoring their children’s use of dental products and ensuring they avoid routine swallowing of fluoride-containing toothpastes and mouthrinses.10

COMMUNITY WATER FLUORIDATION BENEFITS

Fluoridated water protects the strength of the tooth structure, prevents tooth decay, and remineralizes teeth that are in the active stage of the demineralization process.11 Current evidence continues to support water fluoridation as a safe and effective method for reducing dental caries among children12 and adults.13 A recent systematic review investigated the effects of community water fluoridation in the prevention of dental caries.12 The study found that children living in fluoridated areas had 35% fewer caries lesions, restorations, and missing teeth due to decay on their primary teeth.12 Additionally, permanent teeth among children living in areas with fluoridated water had 26% fewer dental cavities, restorations, and missing teeth.12 Another systematic review assessed the effects of community water fluoridation in the prevention of dental caries among adults living in fluoridated areas vs adults who were lifelong residents in nonfluoridated areas.13 The review found that adults of all ages who lived in fluoridated communities had fewer caries lesions at the coronal and root surfaces than those who lived in nonfluoridated areas.13

CONTROVERSY

Anti-fluoride activists oppose the fluoridation of community water systems. The anti-fluoride argument has changed through the years—as it is usually dependent on current public interests—to fuel the debate. For example, in the latter part of the 20th century, anti-fluoridationists frequently argued that community water fluoridation was a communist plot.14 This argument is not as popular today. Now, anti-fluoridationists—recognizing that public interest has become more focused on healthy lifestyles—have found the idea that water fluoridation causes health problems to be more enticing.14 The lack of supporting evidence has never stopped these activists from arguing that water fluoridation causes disease, including cancer.14 A report reviewing decades of research and more than 50 human epidemiologic studies concluded that optimal fluoridated water does not increase the risk of cancer in humans.15 A more in-depth review of the current evidence can be found on the National Cancer Institute website (Table 1).

Another anti-fluoride argument is that numerous fluoride products are now available to consumers, thus, community water fluoridation is no longer necessary. Although the rate of dental caries among some groups in the US has improved over the past few decades, the prevalence of oral health disparities remains high for many racial and ethnic minorities and those of low socioeconomic status.16Additionally, these groups are more likely than affluent populations to have untreated dental caries.16 The prevalence of dental caries among underrepresented Americans demonstrates the lack of access or use of fluoride products, and highlights the continued need for community water fluoridation.

IMPACT OF SOCIAL MEDIA

As the use of the Internet has become ubiquitous in the US, the propagation of misinformation regarding community water fluoridation has flourished.3 A 2014 study showed that anti-fluoride websites dominate the Internet compared with pro-fluoridation sites.17 Not only are pro-fluoridation websites fewer in number, they also receive drastically fewer “hits” when compared with anti-fluoridation sites.17

Research also indicated that social network platforms, such as Facebook, had 193 anti-fluoridation groups/pages, whereas no pro-fluoride groups/pages were found. Thus, patients accessing the Internet for community water fluoridation information are consistently exposed to misinformation.17 This study also investigated Twitter, and found most common anti-fluoridation “tweets” cited increased cancer risk (13%), uselessness of fluoridation (12%), and fluoride is poison (10%) as the most common objections.17 Oral health professionals must be prepared to counter the misinformation patients are commonly receiving from various social media outlets.

ROLE OF ORAL HEALTH PROFESSIONALS

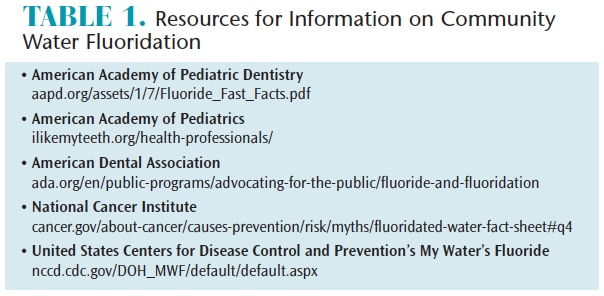

Oral health professionals are in an ideal position to inform patients about the benefits of community water fluoridation—not once, but at every recare appointment. Becoming confident in initiating a conversation about community water fluoridation is the first step. Table 1 lists websites that provide patient handouts and professional guidance on approaching the fluoridation issue in practice. Additionally, clinicians should be informed about water fluoridation status in their community and state. Knowing which communities have public water systems vs well water is a good start to improving water fluoridation knowledge. Using zip codes, the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention provides water fluoridation information at the state and local level.

In summary, community water fluoridation is a safe and effective measure to fight dental caries at all ages. The anti-fluoride agenda is widespread. To counter this misinformation, the pro-fluoride message must be routinely discussed with patients. Oral health professionals are key stakeholders in the promotion of community water fluoridation and are obligated to improve their knowledge on the topic. Informed professionals will have the confidence to play an important role in improving the oral health of the communities in which they serve.

REFERENCES

- United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Community Water Fluoridation. Community water fluoridation. Available at: cdc.gov/fluoridation/index.html. Accessed March 26, 2018.

- US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Ten great public health achievements—United States, 1900-1999. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 1999;48:241–243.

- Allukian M, Carter-Pokras OD, Gooch BF, et al. Science, politics, and communication: The Case of Community Water Fluoridation in the US. Ann Epidemiol. May 29, 2017. doi:10.1016/j.annepidem.2017.05.014

- US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Data & Statistics. Community Water Fluoridation. Available at: cdc.gov/fluoridation/statistics/index.htm. Accessed March 26, 2018.

- Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion. Oral Health: Healthy People 2020. Available at: healthypeople.gov/2020/topics-objectives/topic/oral-health/objectives. Accessed March 26, 2018.

- US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. About Fuoride. Community Water Fluoridation. Available at: cdc.gov/fluoridation/faqs/about-fluroride.html. Accessed March 26, 2018.

- Community Preventive Services Task Force. Oral Health: Preventing Dental Caries, Community Water Fluoridation. Available at: thecommunityguide.org/sites/default/files/assets/Oral-Health-Caries-Community-Water-Fluoridation_3.pdf. Accessed March 26, 2018.

- US Department of Health and Human Services, Federal Panel on Community Water Fluoridation. US Public Health Service Recommendation for Fluoride Concentration in Drinking Water for the Prevention of Dental Caries. Public Health Rep. 2015;130:318–331.

- US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Fluorosis. Community Water Fluoridation. Available at: cdc.gov/fluoridation/faqs/dental_fluorosis/index.htm. Accessed March 26, 2018.

- Policy on use of fluoride. Pediatr Dent. 2016;38:45–46.

- US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Water Fluoridation Basics. Community Water Fluoridation. Available at: dc.gov/fluoridation/basics/index.htm. Accessed March 26, 2018.

- Iheozor-Ejiofor Z, Worthington HV, Walsh T, et al. Water fluoridation for the prevention of dental caries. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;6:CD010856.

- Griffin SO, Regnier E, Griffin PM, Huntley V. Effectiveness of fluoride in preventing caries in adults. J Dent Res. 2007;86:410–415.

- American Academy of Pediatrics. I Like My Teeth. Campaign for Dental Health. Available at: ilikemyteeth.org/fluoridation. Accessed March 26, 2018.

- US Department of Health and Human Services. Review of Fluoride: Benefits and Risks. Available at: health.gov/environment/ReviewofFluoride. Accessed March 26, 2018.

- Satcher D, Nottingham JH. Revisiting oral health in America: a report of the Surgeon General. Am J Public Health. 2017;107:S32–S33.

- Mertz A, Allukian M. Community water fluoridation on the Internet and social media. J Mass Dent Soc. 2014;63:32–36.

From Dimensions of Dental Hygiene. April 2018;16(4):26-28.