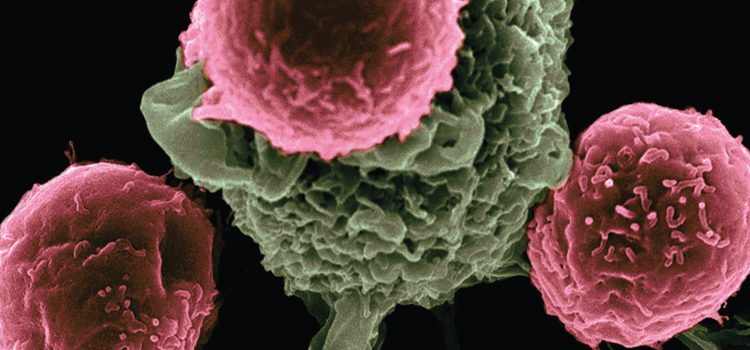

NATIONAL CANCER INSTITUTE/SCIENCE PHOTO LIBRARY

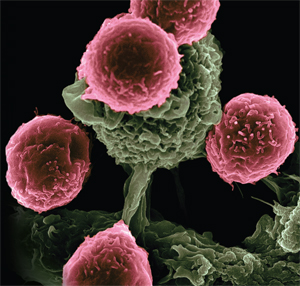

NATIONAL CANCER INSTITUTE/SCIENCE PHOTO LIBRARY

Caring for Patients Undergoing Immunotherapy

Understanding immune response is key to effectively detecting and managing the oral side effects of this treatment.

This course was published in the March 2017 issue and expires March 2020. The author has no commercial conflicts of interest to disclose. This 2 credit hour self-study activity is electronically mediated.

EDUCATIONAL OBJECTIVES

After reading this course, the participant should be able to:

- Discuss the key principles of immunotherapy in cancer treatment and management of autoimmune diseases.

- Describe the basic mechanism of action of immunotherapy.

- Describe the basic mechanism of action of immunotherapy.

The immune system protects the body against illness and infection caused by bacteria, viruses, fungi, or parasites. The immune response involves myriad reactions and processes to repair and remove damaged cells or infection. Immunotherapy—also known as host modulation, biological therapy, or biotherapy—is the prevention or treatment of disease with substances that stimulate the immune response. Collectively, immunotherapy drugs restore, stimulate, or enhance immune system function. Immunotherapy is commonly used to treat various cancers, as well as other conditions, such as autoimmune diseases. Conventional therapies for these diseases rely primarily on cytotoxic and broad-spectrum immunosuppressive agents, such as corticosteroids, to inhibit immune system activity. Serious side effects associated with extensive steroid therapies, however, have stimulated the development of more targeted and less toxic therapies.1

A primary function of the immune system is to defend the body against foreign entities, or antigens. Antibodies are protective proteins synthesized by the B cells of the immune system in response to the presence of antigens. These specialized molecules recognize organisms that invade the body (such as bacteria, viruses, and fungi), and mediate communication between cells to set off a complex chain of events that destroy and eliminate the foreign substance.

Cancer cells are mutated versions of normal cells arising within the body. As a result, the immune system doesn’t recognize them as threats, so an immune response is not activated. Conversely, in cases of autoimmune disease, the body mistakenly identifies healthy cells as antigens and launches an inflammatory attack against them. Consequently, the immunomodulatory properties of antibodies have been used as therapeutic agents for the treatment of such diseases.2,3 Monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) are synthesized in the laboratory and used to therapeutically target specific self-antigens (parts of the body’s own tissues), such as those found on cancer cells (and, in the case of autoimmune diseases, healthy cells). These mAbs recognize and bind exclusively to the self-antigens on the cell surface. Destruction of the targeted cells results from a variety natural functions rendered by antibodies.4,5 The United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has approved more than 30 mAbs to treat cancers and autoimmune diseases. Table 1 offers a condensed list of the more commonly administered mAbs, their therapeutic indications, and when they first became available in the US.6,7

When used in the treatment of autoimmune diseases, immunotherapies suppress inappropriate and/or exaggerated immune responses that stimulate inflammation, whereas cancer immunotherapies help the immune system overcome the mechanisms used by tumors to evade destruction. In addition, some types of cancers can interfere with the immune system’s ability to function properly.3 Tumor necrosis factor (TNF) is a family of cell-signaling proteins that trigger a wide range of proinflammatory actions, including cell death. Studies have shown that targeting/blocking receptors of this protein in tumor cells not only impedes their survival, but also inhibits tumor-promoting properties, such as angiogenesis.8,9 Furthermore, TNF blockage can decrease the inflammatory activity in patients with autoimmune diseases, such as rheumatoid arthritis, Crohn’s disease, psoriatic arthritis, ankylosing spondylitis, ulcerative colitis, and severe chronic plaque psoriasis.10

HEAD AND NECK CANCERS

The immune system plays a key role in the development and progression of head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Research has shown that a breakdown or substandard functioning of the immune system may contribute to the establishment and progression of this type of cancer. Head and neck cancers may be conducive to successful treatment from immunotherapy due to the extent of genetic and immune system defects involved.11 Additionally, most patients present with locally advanced disease and receive a combination of therapeutic approaches with significant toxicity and morbidity. Up to a third of patients eventually develop recurrent or metastatic disease. The prognosis for such patients is bleak and palliative treatment options are limited.12

Novel treatment for patients with head and neck squamous cell carcinoma is essential due to the minimal improvement in patient survival in recent decades. Immune-directed therapies offer a unique therapeutic strategy beyond cytotoxic chemotherapy and physiologically destructive surgical and radiation interventions.11 For example, epidermal growth factor receptors (EGFR) are found to be over-expressed in 80% to 90% of head and neck cancers; EGFR over-expression is associated with reduced survival, making EGFR a logical target for immunotherapy. Inhibition of vascular endothelial growth factor receptor and a group of proteins known as tyrosine kinases has shown potential applications as curative therapy for head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. The mAb cetuximab has been used for more than 10 years as initial treatment of head and neck squamous cell carcinoma, while novilumab was recently approved by the FDA to treat recurrent or metastatic disease. Moreover, several new approaches—including therapeutic vaccines and adoptive T-cell therapy—are under development for treatment of head and neck squamous cell carcinoma in various stages of progression.11,13

ADVERSE EVENTS

While immunotherapy is often considered a nontoxic or less toxic alternative to standard treatments, such as chemotherapy, it can be associated with a distinct group of side effects called immunotherapy-related adverse events (irAEs).14 These range from slight to severe and are potentially life-threatening. Serious irAEs are seen in less than 10% of patients, and, on average, typically emerge 6 weeks to 12 weeks after treatment begins. They are somewhat unpredictable, however, and can start within days of the first dose, many months into treatment, or even after therapy is completed. Many patients with irAEs require permanent discontinuation of the biologic treatment, potentially long courses of corticosteroids, and anti-TNF therapy to modify the inflammatory effects.15 Data pooled from clinical trials identify the most frequent irAEs as hypophysitis, colitis, hepatitis, and rash.16 There are increasing case reports of patients who develop irAEs resembling inflammatory and rheumatic diseases manifesting as arthritis, nephritis, myositis, and polymyalgia-like syndromes.17,18 The risk and gravity of irAEs increases with higher doses and cumulative exposure.

Moreover, immunotherapy is used in combination with other biologics or conventional chemotherapy drugs to increase efficacy, and irAEs tend to be additive with more than one therapy.19 These joint adverse effects often are with gastrointestinal inflammation, which can range from slight irritation to severe colitis—potentially leading to perforation of the bowel. Inflammation of the thyroid can manifest as excessively high activity (hyperthyroidism) or low activity (hypothyroidism). Because the thyroid gland regulates metabolism, growth, and temperature control, typical symptoms of hyperthyroidism include weight loss, fast heart rate, irritability, diarrhea, and feeling warm most of the time. Conversely, the symptoms of hypothyroidism often consist of weight gain, fatigue, dry skin, constipation, and feeling cold. Hyperthyroidism is generally treated with beta blockers, (blood pressure medications that slow the heart rate), combined with management of the patient’s symptoms. Hypothyroidism is readily treated with the thyroid hormone replacement drug levothyroxine.15,20

Other endocrine glands are also subject to autoimmune inflammation as a complication of immunotherapy. Inflammation of the pituitary gland can induce vision changes, confusion, headaches, and other neurologic issues. Similarly, the adrenal glands may become inflamed, leading to fatigue, nausea, and low blood pressure or blood sugar. These complications are treated with replacement of deficient hormones and steroid therapy to reduce inflammation. Pneumonitis occurs in a lower percentage of patients; its manifestations include shortness of breath, coughing, and wheezing. It is often associated with low oxygen-saturation levels in the blood. Along with the supportive measures of supplemental oxygen and possibly antibiotics, steroid regimens are the keystone of treatment.15,20

Rash is another frequent secondary response to immunotherapy, often appearing on the trunk, hands, and feet, although it may be more diffuse. Management is based on extent and severity—from rashes requiring minor interventions with topical steroids and medications for itching to hospitalization and administration of intravenous steroids.15 Serious adverse events can affect multiple organs, including skin, gastrointestinal tract, kidneys, both peripheral and central nervous systems, liver, lymph nodes, eyes, pancreas, and endocrine system.14 Accordingly, treatment with immunotherapy requires vigilant follow-up, including regular physical examinations and blood work, as well as close communication with the patient about new symptoms that may materialize between scheduled visits. Most irAEs can be treated effectively and are reversible if detected and treated early.15 Fortunately, the majority of such reactions can be controlled with immune-suppressive drugs, such as corticosteroids and antihistamines, to counteract the over-active inflammatory response.

COMMON TOXICITY CRITERIA

In 2009, the National Cancer Institute issued the Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE) version 4.0, also called “common toxicity criteria.” It is the standard classification and severity grading scale for adverse events in cancer therapy, and is used for the management of chemotherapy administration and dosing. The CTCAE is also used in clinical trials to provide standardization and consistency in the definition of treatment-related toxicity. Using CTCAE, adverse events are graded on a scale from 1 to 5. Grades 1 to 3 represent progressive worsening in severity or frequency of the toxicity, and interference with self-care and the performance of daily activities; these events warrant clinical intervention.

Clinicians, rather than patients, report adverse events for the standardized classification and scale;21 however, the FDA and other groups have stated that the patient is best positioned to report his or her own symptoms. The National Cancer Institute Patient Reported Outcomes—Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (PRO-CTCAE) is a patient-reported outcome measurement system developed to characterize the frequency, severity, and interference of 78 symptomatic treatment toxicities, including pain, fatigue, nausea, and cutaneous side effects, such as rash and hand-foot syndrome. These 78 symptoms are assessed relative to one or more distinct attributes, including presence or absence, frequency, severity, and/or interference with usual or daily activities. Responses are provided on a 5-point scale, and the recall period is the past 7 days. The PRO-CTCAE system is designed to enhance the quality of adverse event data reporting, represent the patient perspective of the experience of symptomatic adverse events, and improve detection of potentially serious adverse events. Thus, the systematic assessment of symptomatic adverse events using patient-reported outcomes provides additional information that enhances reporting by clinicians using CTCAE.22

Although the incidence of oral complications associated with immune-based therapies has not been firmly established in the literature, oral effects have been reported anecdotally from clinical studies and case reports. A Phase I clinical trial using mAbs for advanced melanoma reported mild to moderate grades of xerostomia in 6.5% of patients treated with nivolumab, and 3% of those treated with pembrolizumab.23 The mAb cetuximab was used as part of a combination therapy in a Phase II trial for nasopharyngeal cancer, and severe oral mucositis was noted as an acute adverse event.24 In the case report of a 77-year-old woman being treated with nivolumab for a lung adenocarcinoma, an outbreak of bullous pemphigoid manifested shortly after treatment.25

These examples highlight the key role oral health professionals play in identifying and managing adverse oral events—regardless of the type of therapy provided. In addition, oral complications may be under-recognized by patients and the medical team. Studies using other cytotoxic and targeted agents have shown very little documentation of oral involvement among participants. Potential reasons include lack of awareness of oral side effects or patient fear that admitting side effects could lead to withholding of lifesaving or life-prolonging immunotherapy. Patients might also expect these side effects to improve after therapy and they may not understand that there are long-term implications of delayed supportive care.26 Comprehensive knowledge and background in the oral-systemic connection position oral health professionals as vital members of the interprofessional team caring for patients undergoing cytotoxic, as well as immune-based therapies. Additionally, oral health professionals can help bridge the information gap that often occurs between patients and oncology staff, and serve as both patient advocates and educators.

CONCLUSION

Targeted and biologic therapies offer promising approaches in the treatment of cancer and autoimmune diseases. The rising number—and increased survival—of patients treated with biotherapies affirms this as a relevant clinical question when looking to the literature for the best evidence. A high level of awareness of potential irAEs by patients and health care providers is essential for early recognition and timely management. Identifying and managing irAEs requires a multidisciplinary approach to help reduce morbidity and prevent interruptions to therapy. Oral health professionals who are knowledgeable about immune responses are well positioned to work with patients who have undergone, or will undergo, immunotherapy.

REFERENCES

- Rosenberg SA. Decade in review-cancer immunotherapy: entering the mainstream of cancer treatment. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2014;11:630–632.

- National Cancer Institute. Biological therapies for cancer. Available at: cancer.gov/about-cancer/treatment/types/immunotherapy/bio-therapies-fact-sheet. Accessed February 16, 2017.

- Caspi RR. Immunotherapy of autoimmunity and cancer: the penalty for success. Nat Rev Immunol. 2008;8:970–976.

- Suzuki M, Kato C, Kato A. Therapeutic antibodies: their mechanisms of action and the pathological findings they induce in toxicity studies. J Toxicol Pathol. 2015;28:133–139.

- Cohen M, Omair MA, Keystone EC. Monoclonal antibodies in rheumatoid arthritis. Int J Clin Rheumtol. 2013;8:541–556.

- Scott AM, Wolchok JD, Old LJ. Antibody therapy of cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2012;12:278–287.

- Ecker DM, Jones SD, Levine HL. The therapeutic monoclonal antibody market. MAbs. 2015;7: 9–14.

- Sasi SP, Yan X, Enderling H, et al. Breaking the ‘harmony’ of TNF-a signaling for cancer treatment. Oncogene. 2012;31: 4117–4127.

- Schaer DA, Hirschhorn-Cymerman D, Wolchok JD. Targeting tumor-necrosis factor receptor pathways for tumor immunotherapy. J Immunother Cancer. 2014;2:7.

- Silva LC, Ortigosa LC, Benard G. Anti-TNF-aα agents in the treatment of immune-mediated inflammatory diseases: mechanisms of action and pitfalls. Immunotherapy. 2010;2:817–833.

- Baumi JM, Cohen RB, Aggarwal C. Immunotherapy for head and neck cancer: latest developments and clinical potential. Ther Adv Med Oncol. 2016;8:168–175.

- Baxi S, Fury M, Ganly I, Rao S, Pfister D. Ten years of progress in head and neck cancers. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2012;10:806–810.

- Lalami Y, Awada A. Innovative perspectives of immunotherapy in head and neck cancer. From relevant scientific rationale to effective clinical practice. Cancer Treat Rev. 2016;43:113–123.

- Bertrand A, Kostine M, Barnetche T, Truchetet ME, Schaeverbeke T. Immune related adverse events associated aith anti-CTLA-4 antibodies: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Med. 2015;13:211.

- Bourke JM, O’Sullivan M, Khattak MA. Management of adverse events related to new cancer immunotherapy (immune checkpoint inhibitors). Med J Aust. 2016;205:418–424.

- Abdel-Wahab N, Shah M, Suarez-Almazor ME. Adverse events associated with immune checkpoint blockade in patients with cancer: a systematic review of case reports. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0160221.

- Kong YC, Flynn JC. Opportunistic autoimmune disorders potentiated by immune-checkpoint inhibitors anti-CTLA-4 and anti-PD-1. Front Immunol. 2014;5:206.

- Gilardi L, Colandrea M, Vassallo S, Travaini LL, Paganelli G. Ipilimumab-induced immunomediated adverse events: possible pitfalls in (18)F-FDG PET/CT interpretation. Clin Nucl Med. 2014;39:472–474.

- Haanen JB, Thienen H, Blank CU. Toxicity patterns with immunomodulating antibodies and their combinations. Semin Oncol. 2015;42:423–428.

- Weber JS, Yang JC, Atkins MB, Disis ML. Toxicities of immunotherapy for the practitioner. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33:2092–2099.

- National Cancer Institute. Common terminology criteria for adverse events (CTCAE) version 4.0. Available at: https://evs.nci.nih.gov/ftp1/CTCAE/CTCAE_4.03_2010-06-14_QuickReference_8.5×11.pdf. Accessed February 16, 2017.

- Kluetz PG, Chingos DT, Basch EM, Mitchell SA. Patient-reported outcomes in cancer clinical trials: measuring symptomatic adverse events with the National Cancer Institute’s patient-reported outcomes version of the Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (PRO-CTCAE). Am Soc Clin Oncol Educ Book. 2016;35:67–73.

- Topalian SL, Sznol M, McDermott DF, et al. Survival, durable tumor remission, and long-term safety in patients with advanced melanoma receiving nivolumab. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32:1020–1030.

- Xu T, Lui Y, Dou S, Li F, Guan X, Zhu G. Weekly cetuximab concurrent with IMRT aggravated radiation-induced oral mucocitis in locally advanced nasopharyngeal carcinoma: results of a randomized phase II study. Oral Oncol. 2015;51:875–879.

- Damsky W, Kole L, Tomayko MM. Development of bullous pemphigoid during nivolumab therapy. JAAD Case Rep. 2016;2:442–444.

- Jackson LK, Johnson DB, Sosman JA, Murphy BA, Epstein JB. Oral Health in oncology: impact of immunotherapy. Support Care Cancer. 2015;23:1–3.

From Dimensions of Dental Hygiene. March 2017;15(3):32-35.