DIGITAL VISION/DIGITAL VISION/THINKSTOCK

DIGITAL VISION/DIGITAL VISION/THINKSTOCK

Caring for the LGBT Community

Providing culturally appropriate treatment is key to improving access to care and health outcomes in lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender patients.

This course was published in the August 2016 issue and expires August 31, 2019. The authors have no commercial conflicts of interest to disclose. This 2 credit hour self-study activity is electronically mediated.

EDUCATIONAL OBJECTIVES

After reading this course, the participant should be able to:

- Discuss the demographics of the lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender (LGBT) community.]

- Identify barriers to care faced by the LGBT community.

- Describe LGBT and gender identifying terminology.

- List communication strategies to improve culturally competent care of LGBT patients within dental practices.

Dental hygienists have a unique opportunity to foster relationships with patients. The ability of dental hygienists to gain patients’ trust and confidence is dependent on their being culturally and linguistically competent. To achieve this, dental hygienists should continually develop their knowledge of culturally diverse groups in order to provide effective care. Diversity is no longer limited to race or ethnicity. Diversity is inclusive of mental ability, physical ability, age, race, ethnicity, gender identity, and sexual orientation.1–3

Lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender (LGBT) health has gone relatively unaddressed in health professional education.4–6 While cultural competency is part of the dental hygiene curriculum, gender and sexual orientation are often missing. Dental hygienists need to develop the skills necessary to self-assess their intercultural communications in order to provide adequate care to all populations, including the LGBT community.

In order for the LGBT community to receive the highest quality care, health professionals should seek continuing education and professional development on LGBT concepts, community-accepted terminology, known health disparities affecting this community, effective communication skills, and inclusive strategies necessary for providing adequate patient care.

The United States has seen notable improvements in oral health. Vulnerable populations, however, are still at increased risk for oral diseases because of limited access to professional dental care. The Healthy People 2020 objectives recognized the LGBT community as a vulnerable population.7,8 These objectives—overseen by the US Department of Health and Human Services (HHS)—are created every 10 years to improve the public’s health, safety, and well-being. According to the HHS, members of the LGBT community face greater health threats than their non-LGBT peers.7,8

Acquiring data on the LGBT population is challenging. While the Healthy People 2020 objectives address national health-related needs, these are not sufficient to properly assess the current needs of the LGBT community.7,8 Gender identity and sexual orientation are not included in the national and state surveys used to create health goals, making it difficult to determine the general and dental health status of the LGBT community.7,8

DEMOGRAPHICS

The fluidity of definitions adds to the challenge of acquiring thorough survey assessment of the LGBT population. An estimated 3.5% of adults in the US identify as lesbian, gay, or bisexual.9 Approximately 0.3% of US adults are transgender.9 Some individuals report experience with same-sex behavior or same-sex attraction, but do not identify as lesbian, gay, or bisexual, making an accurate estimate of total population challenging.

The number of dental hygienists who identify as LGBT is unknown.2 Demographic dental hygiene surveys generally do not include gender identity or sexual orientation. Dental hygienists who identify with this community can aid in addressing the needs of the population, recruiting future professionals from within the community, and creating more comprehensive cultural competency training.3,6

BARRIERS TO PATIENT-CENTERED CARE

There is a long history of discrimination and lack of awareness regarding the health needs of the LGBT community. This population has endured societal stigmatization, discrimination, and denial of civil rights.8 Until 1973, homosexuality was listed as a disorder in the American Psychiatric Association’s Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, and transgender identity remains listed as such.9–12 The inclusion of LGBT as a mental disorder contributed to a history of inhumane treatment, administration of electroshock therapy and chemical castration, and increased violence and hate crimes, particularly toward transwomen of color.9,13,14

Due to the discrimination and stigma, LGBT individuals have often only reluctantly revealed their sexual orientation or gender identity to health care providers.3,5,8,9,15 As a result, this community has experienced high rates of psychiatric disorders, substance abuse, suicide, sexually transmitted infections and diseases, obesity, eating disorders, and other unhealthy behaviors.2,3,6,8,9,13,15

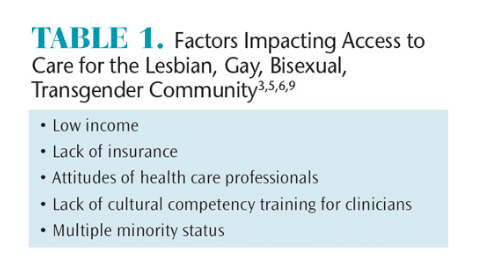

Multiple factors contribute to the lack of adequate access to care for the LGBT community (Table 1).3,5,6,9 Many are of low socioeconomic status and cannot afford the cost of health care services.3,9,10,16 Others are unemployed, underemployed, and/or not provided with health or dental insurance.3,5,6,10,16 Barriers to health care may inhibit LGBT individuals from trusting health care providers. Frequent postponement of medical care when sick or injured has been reported in the LGBT community.9,10,13

Research has shown that the LGBT community, especially transgender individuals, encounters more physical assaults, loneliness, poor mental health, and increased lifetime suicide attempts than their non-LGBT peers.9,10,13,14 The complexity of disparities further increases when an individual is a member of multiple minority groups.3 For example, an LGBT person who is also part of a racial minority may be only half or a third as likely to access care compared with other LGBT individuals.3

When health care is not accessible, members of the LGBT community may be more likely to use illicit hormones and nonmedical grade silicone injections to modify their appearance, and engage in substance abuse and prostitution, raising the risk of human immunodeficiency virus transmission.3,9,14,15

PRINCIPLES OF COMMUNICATION AND TERMINOLOGY

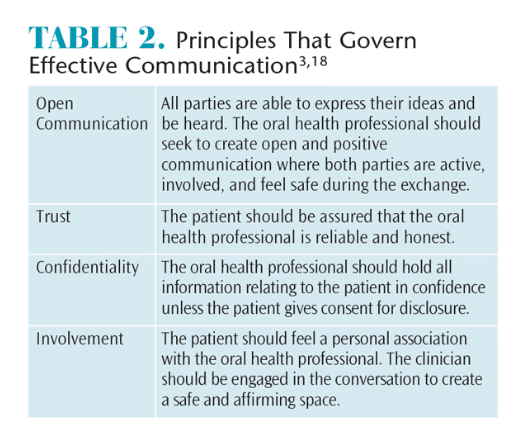

Dental hygienists should assess their cultural identity before attempting competency within another culture.17 Understanding the origin of their own culture, values, and beliefs will aid in understanding the needs of the LGBT community.5,17 Oral health professionals should reflect on their communication styles and govern their patient interaction with these four principles: open communication, trust, confidentiality, and involvement (Table 2).3,18 This is in alignment with the American Dental Hygienists’ Association Code of Ethics and Values, which stipulates that dental hygienists are bound by the values of beneficence, nonmaleficence, confidentiality, justice, and fairness.19

Creating a safe environment for patients where they are able to express their ideas openly—and without judgment—is important. Patients should trust their providers and be assured that they are governed by ethical principles. Patients should feel that dental professionals are concerned for their health and well-being.

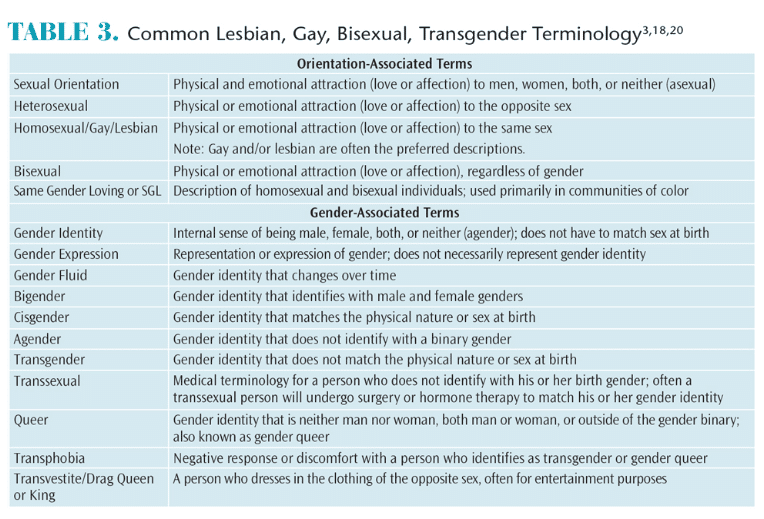

Becoming familiar with common terminology and language used within the LGBT community is important to providing culturally competent care.18 Currently, the most inclusive acronym for this community is LGBTQQIIAA2S (lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer, questioning, intersex, interested, asexual, ally, two spirit). For the workplace, LGBT is an accepted term.

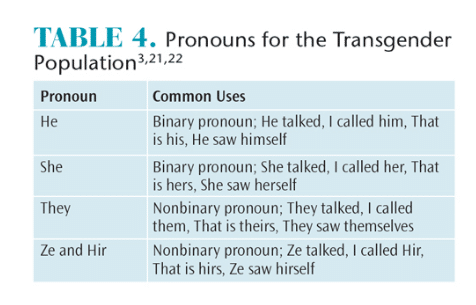

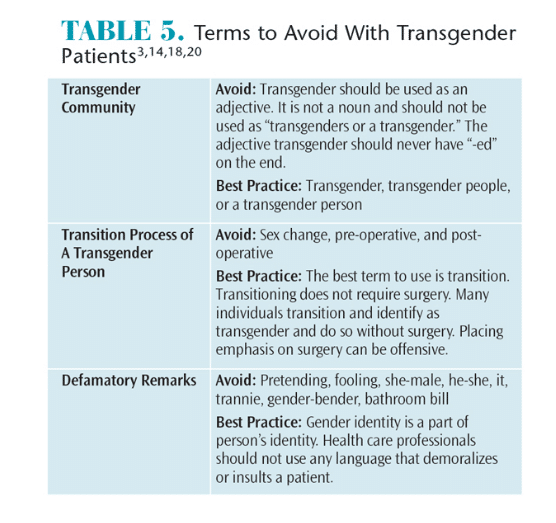

A clear distinction exists between gender identity and sexual orientation. The terms are used independently of one other. Table 33,18,20 provides definitions for common LGBT terminology. Regardless of cultural background, all individuals have a gender identity, sexual orientation, and gender expression.3,18 Oral health professionals should become familiar with common terminology and proper use of preferred pronouns (Table 3 and Table 4,3,21,22 and Table 5).3,14,18,20 When identifying a patient’s preferred pronoun, oral health professionals must keep in mind that some patients prefer to use nongender conforming pronouns such as “they,” “ze,” or “hir” (Table 4).3,18,21

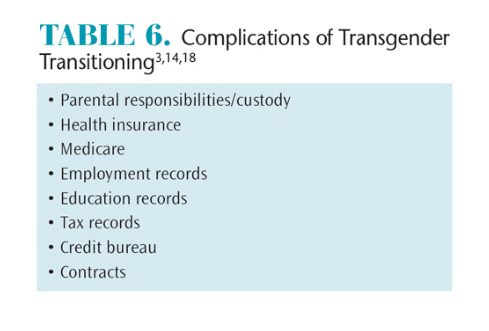

Oral health professionals need to recognize and be culturally sensitive to transgender individuals who are transitioning. This is not always an easy task, as curiosity is a natural response. However, clinicians must be respectful at all times. Table 6 lists some of the challenges a transgender person faces when transitioning.3,14,18 While inquiring whether a transgender patient has undergone surgery is not appropriate, asking how identifying as a transgender person has impacted his or her life is relevant.3,18 Taking the time to understand the patient as a whole person may provide opportunities to gain cultural competency while aiding in communication.

When communicating with a transgender person, the appropriate use of pronouns is important.3,14,18,21 Gender can be categorized in two parts: identity and expression. Gender identity is the internal image of a person that may not necessarily match his or her physical nature. When a person’s self-image does not match his or her gender at birth, this individual is considered transgender. A small group of individuals identify themselves as bigender, gender fluid, or agender (Table 3). Gender expression is how a person decides to express outward appearance. Gender expression can pose a challenge for oral health professionals when determining what pronoun is appropriate. For example, a cisgender (individual whose gender identity corresponds to his or her sex at birth) woman may prefer to wear a suit and tie.

Oral health professionals should ask what pronoun or gender is preferred by the patient (Table 4). This question can be added to the medical history form so that dental hygienists are aware of the patient’s preference.3 If an incorrect pronoun is used, an immediate apology is appropriate. Apologizing to the patient and showing the willingness to learn fosters patient-provider trust.3,22 The goal of the dental hygienist is to maintain a safe and welcoming environment when providing treatment for each patient.

COMMUNICATION STRATEGIES

All patients should be treated with respect and courtesy. It is vital that oral health professionals be comfortable asking patients for their preferences regarding communication.3 Clinicians should speak in an encouraging and culturally appropriate manner. Patients who reveal their identities should never be “outed” to others.3,14

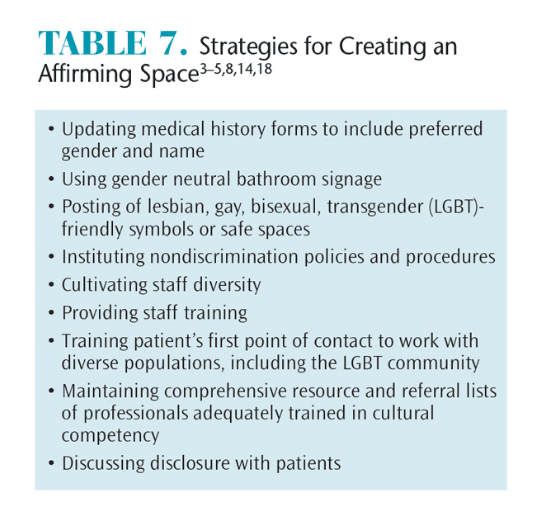

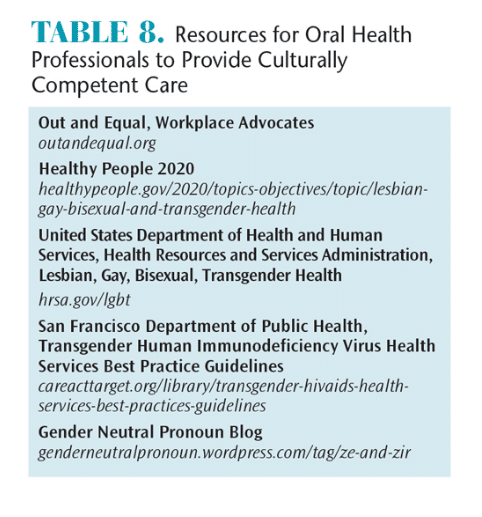

The administrative staff is the first point of contact for patients entering a clinical practice. Staff should be trained to interact with a diverse population.3 Diversity training should include LGBT health issues.3,6 All staff should be educated in cultural competency, and staff diversity needs to be encouraged.18 The practice’s policy and procedures handbook must include nondiscrimination policies and procedures in the event a violation is suspected.3,14,18 Practices should also have a comprehensive resource and referral list of professionals who are trained in cultural competency.3,14 Table 7 provides strategies for creating an affirming space, and Table 8 offers resources for improving cultural competency.3–5,8,14,18

CONCLUSION

Minority populations remain underrepresented in the health professions, including dental hygiene.6 Cultural awareness is an important factor while interacting with patients. Oral health professionals should respect cultural differences, recognize how they may affect patient health, and be able to communicate effectively in cross-cultural circumstances. Until educational institutions begin implementing diversity training that includes gender and sexual orientation, oral health professionals will need to grow their cultural sensitivities and awareness.1 By dong so, clinicians will continue to improve access to care and the health status of underserved populations.

References

- Long M. What does diversity mean to you? Access.2013;13:28.

- Morgan P. Lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender(LGBT) issues in dental hygiene: the invisible minority.Access. 2013;27(3):24–25.

- Woodward B, Eastin J, Millhouse VM, Smith C,Haley J. Advancing effective communication and cultural competency with the LGBT community with special emphasis on the transgender patient. Presented at: Baltimore City Community College; October 29, 2014; Baltimore.

- Cochran B, Robohm J. Integrating LGBT competencies into the multicultural curriculum of graduate psychology training programs: expounding and expanding upon hope and chappell’s choice points: commentary on “extending training in multicultural competencies to include individuals identifying as lesbian, gay, and bisexual: key points for clinical psychology training programs.” Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice. 2015;22(2):119–126.

- Gendron T, Maddux S, Krinsky L, et al. Cultural competency training for healthcare professionals working with LGBT older adults. EducationalGerontology. 2013;39(6):454–463.

- Moll J, Krieger P, Moreno-Walton L, et al. Theprevalence of lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgenderhealth education training in emergency medicineresidency programs: what do we know. Acad Emerg Med. 2014;21:608–611.

- US Department of Health and Human Services.Healthy People 2020. Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, andTransgender Health. Available at: healthypeople.gov/2020/topicsobjectives/topic/lesbian-gay-bisexual-andtransgender-health. Accessed July 19, 2016.

- US Department of Health and Human Services: HealthResources and Services Administration. LGBT Health.Available at: hrsa.gov/lgbt. Accessed July 19, 2016.

- Ard K, Makadon, H. Improving the healthcare oflesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender (LGBT) people:understanding and eliminating health disparities.Available at: lgbthealtheducation.org/wp-content/uploads/12-054_LGBTHealtharticle_v3_07-09-12.pdf. Accessed July 19, 2016.

- Walch SE, Sinkkanen KA, Swain EM, Francisco J,Breaux CA, Sjoberg MD. Using intergroup contact theory to reduce stigma against transgender individuals: impact of a transgender speaker panel discussion. Journal of Applied Social Psychology. 2012;42(10):2583–2605.

- Winters, K. Gender dysphoria diagnosis to bemoved out of sexual disorders chapter of DSM-5.Available at: gidreform.wordpress.com/2012/12/07/gender-dysphoria-diagnosis-to-be-moved-out-ofsexual-disorders-chapter-of-dsm-5. Accessed July 19, 2016.

- Winters K. GID reform in the DSM-F and ICD-11: astatus update. Available at: gidreform.wordpress.com/2013/06/13/gid-refoerm-in-the-dsm-5-and-icd-11-astatus-update. Accessed July 19, 2016.

- King M, Semlyen J, Tai SS, et al. A systematicreview of mental disorder, suicide, and deliberate selfharm in lesbian, gay and bisexual people. BMCPsychiatry. 2008;8:70.

- San Francisco Department of Public Health.Transgender HIV Health Services Best PracticesGuidelines. Available at: careacttarget.org/sites/default/files/file-upload/resources/tgguidelines.pdf. Accessed July 19, 2016.

- Silverman M. Issues in access to healthcare bytransgender individuals. Women’s Rights Law Reporter.2009;30(2):347–351.

- Fredriksen-Goldsen KI, Simoni JM, Kim H, et al.The health equity promotion model:reconceptualizations of lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) health disparities. Am J Orthopsychiatry. 2014;84:653–663.

- Nathe CN. Dental Public Health and Research:Contemporary Practice for the Dental Hygienist. 3rd ed.Upper Saddle River, New Jersey: Pearson; 2011.

- Out & Equal Workplace Advocates. BuildingBridges Part I [webinar]. April 21, 2015.

- American Dental Hygienists’ Association. Bylawsand Code of Ethics. Available at: adha.org/resourcesdocs/7611_Bylaws_and_Code_of_Ethics.pdf. Accessed July 19, 2016.

- Out & Equal Workplace Advocates. LGBT CulturalCompetency Terminology. Available at: outandequal.org/wpcontent/uploads/2014/12/TerminologyApril2011.pdf. Accessed July 19, 2016.

- Buzzfeed. Why pronouns matter for trans people.Available at: youtube.com/watch?v=N_yBGQqg7kM.Accessed July 19, 2016.

- Gender Neutral Pronoun Blog. The Need for a Gender-Neutral Pronoun. Available at: gender neutralpronoun.wordpress.com/tag/ze-and-zir. Accessed July 19, 2016.

From Dimensions of Dental Hygiene. August 2016;14(08):70–73.