STARAS/ISTOCK/THINKSTOCK

STARAS/ISTOCK/THINKSTOCK

Treating Patients With Fibromyalgia

Implementing patient management strategies and oral self-care modifications will help this population maintain their oral health.

This course was published in the August 2016 issue and expires August 2019. The authors have no commercial conflicts of interest to disclose. This 2 credit hour self-study activity is electronically mediated.

EDUCATIONAL OBJECTIVES

After reading this course, the participant should be able to:

- Describe the characteristics of fibromyalgia (FM).

- Discuss the pathophysiology of FM.

- List FM’s oral manifestations.

- Discuss dental hygiene management considerations for patients with this autoimmune disease.

Fibromyalgia (FM) is a complex multisystem disorder of idiopathic origin characterized by widespread musculoskeletal pain and tenderness. It is the most common cause of chronic whole-body pain in the United States and affects 3% to 6% of the population worldwide.1,2 FM can result in severe functional impairments that may lead to diminished quality of life. Dental hygienists need to be cognizant of FM’s etiology and other characteristics because oral and perioral areas are frequently involved.

Worldwide, the incidence of FM is 6.88 per 1,000 men and 11.28 per 1,000 women.3 Between 80% and 90% of people diagnosed with FM are women, although it can affect anyone regardless of age or ethnicity.4 While the condition is most common in middle-aged and older women, it also affects children and men.5 Prevalence of fibromyalgia peaks among middle-aged adults but incidence increases with age, as 80% of adults meet criteria for diagnosis by age 80.6

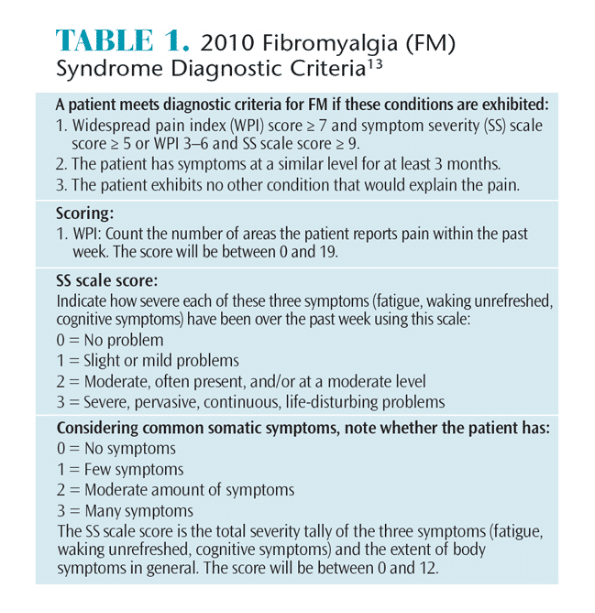

The hallmark characteristic of FM is chronic and diffuse musculoskeletal pain.7,8 Pain may occur on both sides of the body, as well as above and below the waist. It is described as stabbing, throbbing, deep, aching, and/or intense burning. Radiating diffusely over many body areas, initial pain symptoms may be localized to the neck and shoulders. Although symptoms vary from one patient to another, hyperalgesia (exaggerated or increased sensitivity to stimuli) and dysesthesia (an unpleasant, abnormal sense of touch typically affecting the extremities) are common.7,8 In addition, allodynia (a pain response from stimuli that do not normally provoke pain) has been associated with the disorder.8 Some individuals have mild symptoms requiring no medical intervention, while others experience uniform pain and constant exhaustion. Some report pain that is worse in the morning that improves during the day but worsens again at night.9,10 The pain is often exacerbated by sleep dysfunction, physical or emotional stresses, overexertion and/or cold or damp weather.9,11,12 Table 1 includes the criteria for FM diagnosis.13

Pain, fatigue, and sleep disturbances form a triad of symptoms that affect most patients with FM.9 These symptoms may be accompanied by generalized morning stiffness, paresthesia, irritable bowels, bladder abnormalities, concentration/memory problems, and migraine headaches.4,7,8 The onset of symptoms can occur suddenly; however, they most often appear gradually, stabilize in the first year, and remain stable subsequently.

Up to 90% of patients with FM report some form of sleep disruption.14 Some people report difficulty falling asleep. Most awaken after a few hours of sleep feeling alert and then are not able to sleep soundly again until morning (terminal insomnia).15 In FM, sleep and pain appear to have a synergistic relationship insofar that a lack of sleep is associated with increased pain and more pain may lead to less sleep.16 Low-quality sleep is associated with poor health outcomes, increased pain responses, decreased physical function, depression, and fatigue among individuals with FM.14–16

Another common symptom is cognitive deficiency, or what is sometimes termed “fibro fog.”17,18 This consists of long- and short-term memory loss, mental slowness, loss of vocabulary, concentration difficulties, deficiencies in attention span, and decreased ability to perform tasks that require rapid thinking.19 The cognitive deficiency appears to be related to the degree of pain experienced, but not directly caused by pain. It is also likely linked to sleep disturbances. Increased anxiety and depression have been associated with aggravating the physical functioning of patients with FM when compared with low levels of depression and anxiety.20

FM can mimic other chronic conditions, making diagnosis difficult. Diseases with similar signs and symptoms, such as bursitis, Lyme disease, tendinitis, anemia, rheumatoid arthritis, systemic lupus, and undiagnosed cancer, can be misdiagnosed as FM.7–9 The lack of objective tests to definitively diagnose fibromyalgia is a concern, and patients often report a long delay between onset of symptoms and diagnosis, often ranging from 2 years to 3 years.1

PATHOPHYSIOLOGY

FM has a multifactorial etiology and suspected causes include irregularities in pain pathways, genetic predisposition, and environmental triggers.9,19,21 The main source of pain appears to be in the central nervous system (CNS). Increased excitability of neurons found in the spinal cord (CNS sensitization), makes neurons hypersensitive to stimuli. Central sensitization is characterized by a magnified pain response that includes heightened intensity, exaggerated duration, and wide anatomical distribution.19

Nonrestorative sleep appears related to neuroendocrine dysfunction, specifically the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis, as well as the autonomic nervous system.9,19 The HPA axis regulates stress, and cortisol is released in response to stress. During chronic stress, cortisol levels become elevated due to sustained activation of the adrenal cortices. In an effort to restore homeostasis, the negative feedback loop is exaggerated, leading to occasional cortisol deficiencies.9 Individuals with FM are thought to experience sleep disturbances due to low cortisol levels.9

Irregular levels of the neurotransmitters serotonin, norepinephrine, substance P, and dopamine appear related to FM.2,7,9,21,22 Substance P is consistently elevated in people with FM and is thought to amplify sensitivity and heightened awareness of pain.21 The most common biochemical abnormality found among individuals with FM is low serotonin levels. This is important because of serotonin’s effects on delta sleep and pain modulation.9,10,21,22 Serotonin, norepinephrine, and dopamine also down-regulate pain; thus, the decreased levels of these neurotransmitters extend pain in patients with FM.7,9

FM may be attributed to genetics, environmental factors, or both. Mothers, siblings, and children of people with FM are more likely to develop the syndrome compared with the general population. As such, the high occurrence of FM in families may be attributed to genetic or commonly experienced epigenetic affectors.8,21,23

The most perceived triggering events of FM onset include chronic stress, emotional trauma, and acute illness.24 Physical stressors include serious infection, traumatic injury, surgery, motor vehicle accidents, and other causes of pain.21,24 Catastrophic events or abuse are psychosocial factors that have also been correlated with development of FM symptoms.21,24

TREATMENT

A comprehensive treatment approach that combines physical, psychological, and behavioral factors and includes pharmacological and nonpharmacological tactics is valuable in managing FM.1,22,24,25 Treatment is aimed at alleviating symptoms and improving quality of life. The US Food and Drug Administration has approved pregabalin, duloxetine, and milnacipran for FM management.1,4,19,25 The three most effective nonpharmacological therapies for FM are physical exercise, patient education, and cognitive behavioral therapy.8 Alternative treatment therapies—such as acupuncture, hydrotherapy, massage, yoga, chiropractic manipulation, relaxation therapy, and tender-point injections—may help. Unfortunately, evidence regarding the efficacy of these therapies is lacking.8,25

ORAL CONCERNS

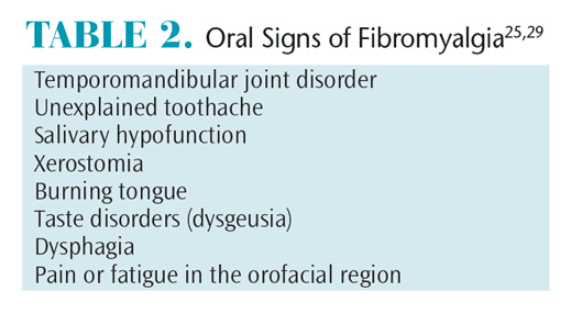

Patients with FM are 31 times more likely to report facial pain than those without the disorder, with 75% reporting myofascial pain.26,27 Pain in the temporomandibular joint (TMJ) and pain during mandibular opening, closing, and lateral movements are common in patients with FM.26 Additionally, limited mouth opening is reported to be 10 times more common among patients with FM than those without it. The average maximum voluntary mouth opening for patients with FM is 41 mm, compared with 44 mm in typical patients.26 Masticatory muscle pain is reported by approximately 93% of people with FM.27 Common oral findings are found in Table 2.

Patients with FM are at high risk of temporomandibular disorder (TMD).26–28 FM may play a role in TMD onset because more people with FM develop TMD than individuals with TMD who develop FM.25–27 The comorbidity of TMD and FM may result from alterations in pain perception; thus, typical treatments for TMD may not help people with FM. Occlusal splints have not been shown to be successful for treating myofascial pain in people experiencing the diffuse pain commonly caused by FM.25,29 However, tactile stimulation (massage) has been beneficial for treating TMD in patients with FM.25,29

Xerostomia is experienced by approximately 70% of people with FM.28 Medications used to manage FM, such as antidepressants, muscle relaxants, hypnotics, analgesics, and anticonvulsants, may induce xerostomia.29 However, only 27.5% of people with FM and xerostomia take xerostomia-inducing medications, suggesting the high prevalence of xerostomia is independent of drugs that cause dry mouth.28

Glossodynia (burning tongue) is observed in approximately one-third of patients with FM.28 Resulting from CNS sensitization, glossodynia may be a manifestation of hyperalgesia and allodynia.28 Because depression may contribute to the onset of oral burning, patients with glossodynia may benefit from tricyclic antidepressants.2,22,29

Dysgeusia (taste distortion) is reported by more than one-third of patients with FM.28 It may be an adverse effect of medications. If patients take a medication that commonly causes taste alterations, such as amitriptyline, cyclobenzaprine, fluoxetine, venlafaxine, or zopiclone, they can consult their physician about trying a different medication without dysgeusic effects.25,29

PATIENT MANAGEMENT

Promoting health and preventing complications is a vital part of treatment planning for patients with FM.13 Thus, interprofessional collaboration is important when caring for these patients.9 Open communication between a patient’s physician, physical therapist, psychologist, and oral health professional is important to optimize treatment and improve quality of life. Additionally, early interventions may help prevent systemic complications from oral disease.

Ensuring patient comfort during dental hygiene care is important. Determining the time of day the patient functions best and scheduling appointments accordingly will enhance the chances for success. Many patients with FM?experience more severe pain, fatigue, and muscle stiffness in the early morning. Thus, a late-morning or afternoon appointment may be preferable.9

A detailed history of FM should be obtained, including the date of diagnosis, course of the syndrome, and current medication usage. The patient should be assessed for orofacial pain and headaches that may be indicative of TMD. In addition, possible oral manifestations including salivary hypofunction, bruxism, glossodynia, and dysgeusia should be assessed.25 A thorough evaluation of the TMJ and muscles of mastication should be conducted. Because of the chronic orofacial pain experienced by patients with FM, oral examinations may cause discomfort.25 Therefore, a gentle approach should be used. Additionally, if FM is not diagnosed but suspected, the oral health professional should refer the patient for further evaluation.29

Patients with FM may not be able to tolerate long appointments. They may be uncomfortable in a supine position, so the dental chair needs to be adjusted. A massage pad or cervical pillow for the neck and support for the back and legs should be available.11 If possible, the patient’s treatment plan should be broken up to accommodate short appointments or allow time for periodic breaks during treatment.25

Any physical or psychological stressor can trigger CNS dysregulation and increase pain response in patients with FM.20 Therefore, creating a treatment environment that is as stress free as possible is an important strategy.13 Developing a trusting relationship between the patient and the practitioner, along with effective pain management strategies are seminal to reducing anxiety and stress. Soothing music, eliminating extraneous noises, aromatherapy, and anticipatory guidance may promote relaxation. Muscle relaxants and anti-inflammatory medications for use both before and after the appointment can improve comfort. These medications may also help patients keep their mouths open wide for a longer time. Deep breathing or relaxation exercises may be helpful prior to appointments. Preventing oral infections is important because they increase stress on the body, which can aggravate FM symptoms.12,30 The antibiotics erythromycin and clarithromycin should be avoided because they may increase therapeutic levels of other medications patients with FM may be taking, such as citalopram.

Modifications will likely be necessary to ensure patient comfort. Both topical and local anesthetic agents are recommended to manage pain during scaling and root planing. Patients may request additional anesthetic than what is customary for a particular procedure. Patients taking amitriptyline, venlafaxine, and duloxetine should not be given local anesthetic agents containing epinephrine because of the potential for adverse drug interactions.29 Some patients may require intravenous sedation for treatment.

Practitioners may find a mouth prop (bite block) useful because it limits stress on the TMJ, while making it easier for those with limited mouth opening and whose facial muscles quickly fatigue.25,30 Because jaw pain may persist after the appointment, patients with FM should be encouraged to eat a soft diet and chew foods as evenly as possible on both sides of the mouth. They should also minimize mouth opening and avoid gum chewing. Warm facial compresses (unless heat exacerbates symptoms), analgesics, or muscle relaxants may also help.29 Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, such as aspirin and ibuprofen, should not be recommended for patients taking selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors because they may increase the risk of prolonged bleeding.29 For patients with TMD, muscle trigger points involving the masseter and temporalis muscles can be managed with ice packs followed by moist heat.25

Patients with FM are often hypersensitive to stimuli such as noise, odors, heat, cold, touch, and light.19,22 Avoiding strong aromas, such as perfumes, may be helpful. Patients should be consulted regarding how bothersome extraneous noises such as background music, televisions, or powered instruments are so that these can be limited.30 Many patients with FM report that temperatures most people report as cool feel extremely cold. Thus, a blanket or warm neck roll should be readily available.25 Light hypersensitivity may also occur. Dark eyewear should be provided during the appointment, and clinicians should avoid shining the operatory light in patients’ eyes.

Because of the possibility of cognitive dysfunction, patients may need to be reminded of upcoming appointments more frequently. Repeating instructions along with providing written self-care instructions and educational materials may be warranted.30

Some patients may experience difficulties discerning whether oral discomfort is associated with chronic FM pain or acute pain from an oral condition. Educating patients about the difference is important.29 Frequent recare is necessary to ensure oral diseases are identified early.30

Power toothbrushes, flossing devices, and oral irrigators may assist patients with self-care. However, the noise from a powered device may be a problem for those with heightened sound sensitivity and on-off switches may be problematic for patients with dexterity problems. Modifying the toothbrush by extending or enlarging the handle may help.

Patients with FM and xerostomia should be encouraged to manage their dry mouth symptoms. Xylitol mints and lozenges can be recommended instead of xylitol gum to stimulate salivation without stressing masticatory muscles. Saliva substitutes can help lubricate the mouth for short-term relief of symptoms. Prescription medications with cholinergic properties may assist in providing more sustained lubrication.

CONCLUSION

FM is a common but complex disorder that encompasses symptoms of chronic, diffuse body pain, fatigue, psychological symptoms, cognitive deficiency, and sleep disturbances. Oral manifestations of FM are common and affect the oral and overall health of the patient. Dental hygienists must be cognizant of oral and extraoral signs and symptoms of FM, patient management strategies, and oral self-care modifications. Additionally, dental hygienists should be prepared to make appropriate adjustments when treating patients with FM to ensure optimal hygiene care can be provided.

References

- Paxton S. Perioperative care of the patient withfibromyalgia. AORN J. 2011;93:380–386.

- Morin AK. Fibromyalgia: a review of managementoptions. Formulary. 2009;44:362–373.

- Queiroz LP. Worldwide epidemiology of fibromyalgia.Curr Pain Headache Rep. 2013;17:356.

- National Fibromyalgia and Chronic Prevalence.Available at: fmcpaware.org/fibromyalgia/prevalence.html. Accessed July 15, 2016.

- Walitt B, Nahin RL, Katz RS, et al. The prevalence andcharacteristics of fibromyalgia in the 2012 National Health Interview Survey. PloS One. 2015;10:1–16.

- National Fibromyalgia and Chronic Pain Association.Men and Fibromyalgia. Available at: fmaware.org/about-fibromyalgia/prevalence/men-fibro. Accessed July 15, 2016.

- Longley K. Fibromyalgia: etiology, diagnosis,symptoms and management. Br J Nurs.2006;15:729–733.

- Clauw D. Fibromyalgia: A clinical review. JAMA.2014:;311:1547–1555.

- Weirwille L. Fibromyalgia: diagnosing and managing a complex syndrome. J Am Acad Nurse Pract. 2012:24:184–192.

- Huynh CN, Yanni LM, Morgan LA. Fibromyalgia:diagnosis and management for the primary healthcare provider. J Womens Health (Larchmt). 2008;17:1379–1387.

- Little J, Falace D, Miller C, Rhodus N. DentalManagement of the Medically Compromised Patient. St. Louis, Missouri: Elsevier; 2013.

- Ahola K, Saarinen A, Kuuliala A, et al. Impact of rheumatic diseases on oral health and quality of life. Oral Diseases. 2015;21:342–348.

- Wolfe F, Clauw D, Fitzcharles M, et al.Fibromyalgia criteria and severity scales for clinical and epidemiological studies: a modification of the ACR preliminary diagnostic criteria for fibromyalgia. J Rheumatol. 2011;38:1113–1122.

- Pimentel MJ, Gui MS, Reimão R, Rizzatti-BarbosaCM. Sleep quality and facial pain in fibromyalgia syndrome. Cranio. 2015;33:122–128.

- Diaz-Piedra C, Catena A, Sánchez AI, Miró E,Martínez MP, Buela-Casal G. Sleep disturbances in fibromyalgia syndrome: the role of clinical and polysomnographic variables explaining poor sleep quality in patients. Sleep Med. 2015;16:917–925.

- Theadom A, Cropley M, Humphrey KL. Exploring the role of sleep and coping in quality of life in fibromyalgia. J Psychosom Res. 2007:62;145–151.

- Kravitz HM, Katz RS. Fibro fog and fibromyalgia: a narrative review and implications for clinical practice. Rheumatol Int. 2015;35:1115–1125.

- Glass JM. Cognitive dysfunction in fibromyalgiasyndrome. J Musculoskelet Pain. 2010;18:367–372.

- Dhar M. Pathophysiology and clinical spectrum of fibromyalgia: a brief overview for medical communicators. American Medical Writers Association Journal. 2011;26(2):50–54.

- Cofford L. Psychological aspects of chronic musculoskeletal pain. Best Prac Res Clin Rheumatolol. 2015;29:147–155.

- Bradley LA. Pathophysiology of fibromyalgia. Am J Med. 2009;122:522–530.

- Peterson EL. Fibromyalgia: management of a misunderstood disorder. J Am Acad Nurse Pract. 2007;19:341–348.

- Kato K, Sullivan PF, Evengard B, Pedersen NL. A population-based twin study of functional somatic syndromes. Psycol Med. 2009;39:497–505.

- Bennett RM, Jones J, Turk DC, Russell IJ, Matallana L.An internet survey of 2,596 people with fibromyalgia. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2007;8:27.

- Jin H, Patil PM, Sharma A. Topical Review: the enigma of fibromyalgia. J Oral Facial Pain Headache. 2014;28:107–118.

- Pimentel MJ, Gui MS, de Aquino LM, Rizzatti-Barbosa CM. Features of temporomandibular disorders in fibromyalgia syndrome. Cranio. 2013;31:40–45.

- Fraga B, Santos E, Farias Neto J, et al. Signs andsymptoms of temporomandibular dysfunction in fibromyalgic patients. J Craniofac Surg. 2012;23:615–618.

- Rhodus N, Fricton J, Carlson P, Messner R. Oral symptoms associated with fibromyalgia syndrome. J Rheumatol. 2003;30;1841–1845.

- Balasubramaniam R, Laudenbach JM, Stoopler ET.Fibromyalgia: an update for oral health providers. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2007;104:589–602.

- Walters A, Tolle SL, McCombs GM. Fibromyalgia syndrome: considerations for dental hygienists. J Dent Hyg. 2015;89:76–85.

From Dimensions of Dental Hygiene. August 2016;14(08):66–69.