Breaking the Genetic Code

Genetic testing may provide oral health professionals with a new avenue to customize patient care and improve preventive treatments and outcomes.

This course was published in the September 2017 issue and expires September 2020. The authors have no commercial conflicts of interest to disclose. This 2 credit hour self-study activity is electronically mediated.

EDUCATIONAL OBJECTIVES

After reading this course, the participant should be able to:

- Identifying the importance of a three-generational family health history.

- Differentiate between direct-to-consumer and professionally based genetic testing.

- Discuss concerns regarding the use of genetic testing.

- List possible future applications of genetic testing.

With the completion of the human genome project in 2003 and the decreased cost of DNA sequencing, DNA testing is becoming available and affordable to everyone.1 More than 1,800 genes associated with disease have been discovered.2 Dental hygienists are concerned with three primary diseases of the oral cavity: caries, periodontal diseases, and oral cancer. Microorganisms and the host immune response are etiologic factors in caries and periodontal diseases; however, recent research has demonstrated a genetic susceptibility to these diseases as well.3–6 Research also suggests a genetic relationship to oral cancer.7,8

The potential to use genetic research to manage systemic diseases through clinical care, improved delivery of preventive oral care, and clinical practice standards for individuals, communities, and global populations is promising. With the advent of oral-systemic links, the genetic basis of systemic diseases and consumer access to affordable DNA sequencing, dentistry and dental hygiene need to become integrated into the genetic arena.

Genomic research has provided valuable information in predicting disease occurrence and in creating preventive pharmacogenetic approaches to treating systemic genetic disorders. Oncology uses genotyping and pharmacogenetics.9 Epigenetics is another area garnering attention, as environmental and maternal stressors during pregnancy influence changes in gene expression without affecting the nucleotide sequence. These changes can manifest in future generations.9 Suggestions for future genetic studies involve identifying genes that promote good health and increase disease resistance in the presence of environmental risk factors.10 The rapid evolution of the genetic environment makes it challenging for oral health professionals to remain current and incorporate genetics into daily practice. Therefore, this paper will review the concepts of genetic core values, generational family health histories in disease assesment, genetic testing, and ethical considerations.

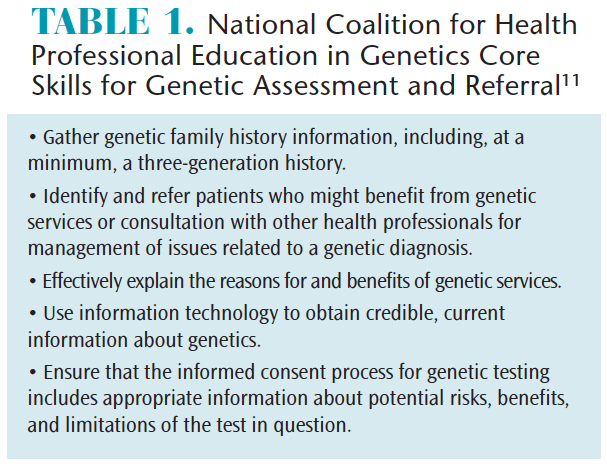

GENETIC CORE SKILLS

Patients are accessing universal and affordable direct-to-consumer (DTC) genetic testing to research their ancestry and health conditions. In some respects, patients may be more familiar with genetic testing than oral health professionals. The National Coalition for Health Professional Education in Genetics (NCHPEG) recommends that health professionals integrate and understand the interaction of genetic, environmental, and behavioral factors in disease predisposition to provide effective, comprehensive treatment for health issues.11 The NCHPEG advocates specific skills all health professionals should learn as part of genetic assessment and referral (Table 1).11

FAMILY HEALTH HISTORY

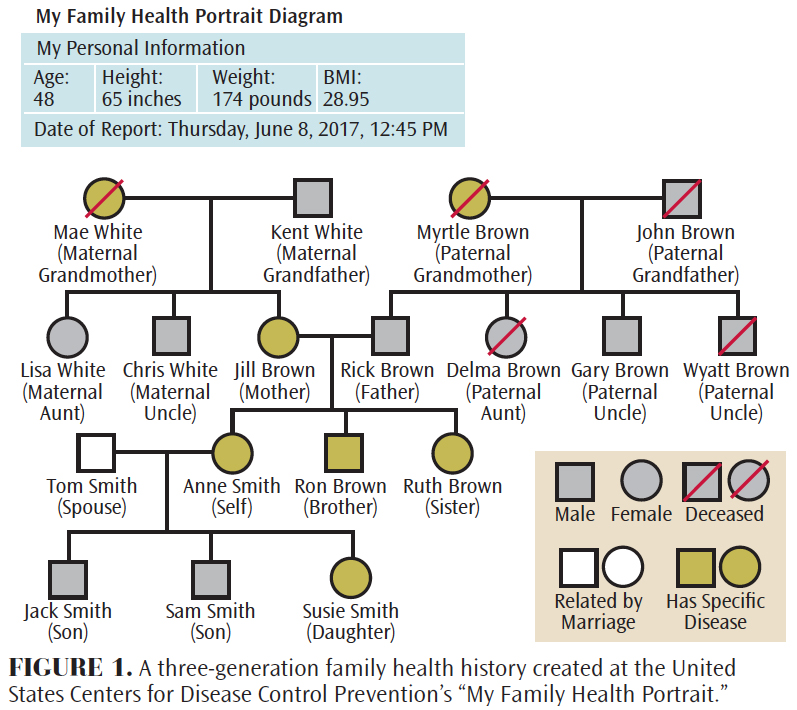

Oral health professionals perform assessments and consider the oral-systemic connection when treating patients, but they do not typically look at patients through a genetic lens. Patients may present with a history of cardiovascular disease, diabetes, oral-facial changes, and even periodontal diseases, without ever having undergone evaluation for genetic predispositions to health problems. A three-generational family health history is helpful in assessing disease susceptibility, evaluating the social/psychological impact of health-related genetic information, and identifying and referring individuals for genetic counseling.

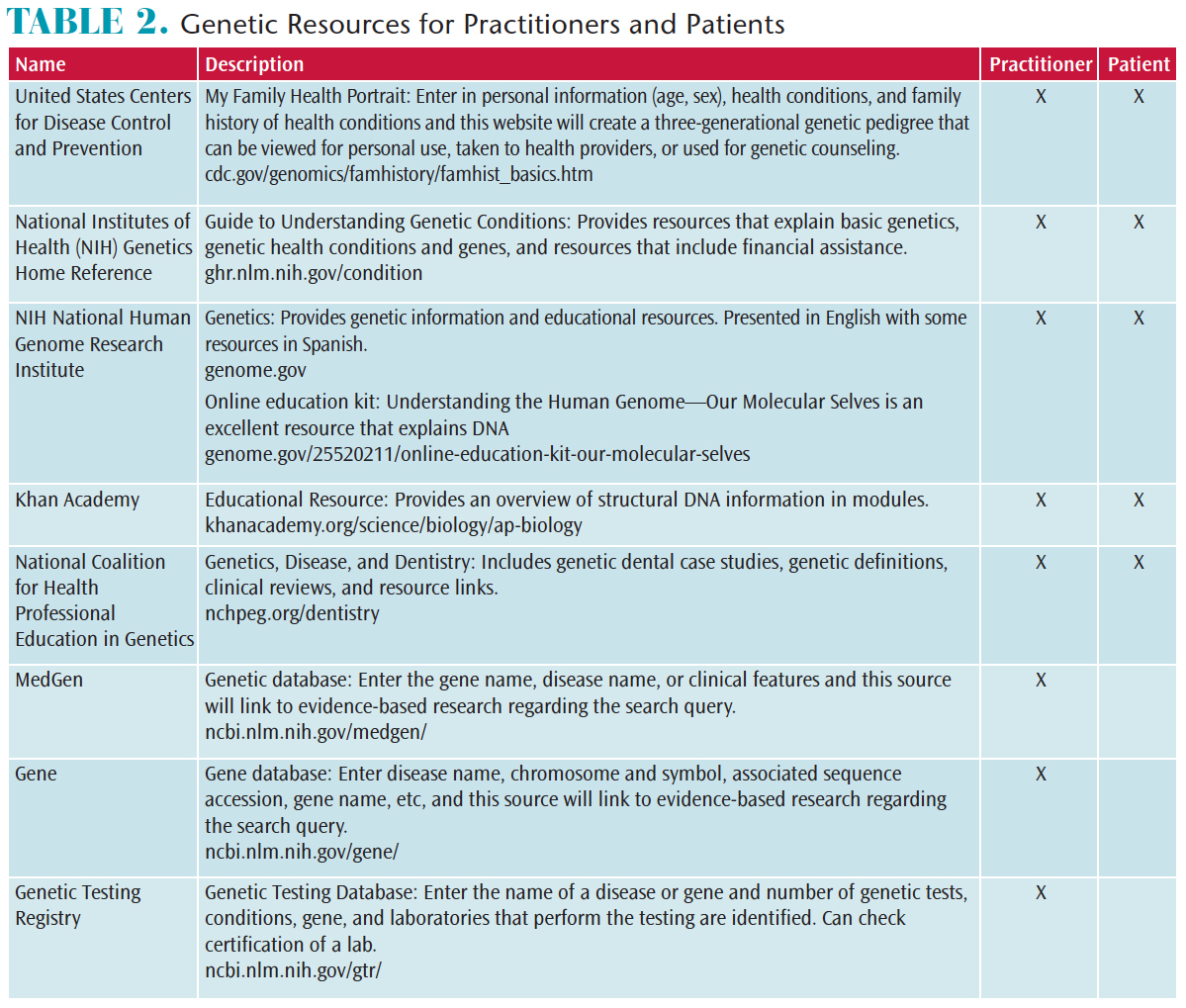

The United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention provides the ability to create a three-generational family health history: cdc.gov/genomics/famhistory/famhist_basics.htm. Figure 1 presents an example of a completed genetic pedigree that illustrates predisposition to various health conditions. This illustration provides an opportunity to educate patients about oral-systemic connections, genetic implications, preventive strategies, and oral health care considerations. As such, patients will have a better understanding of their health status, oral preventive care, and treatment options, so they can make more informed choices about their overall health. Once the family pedigree has been completed, referral for genetic testing or counseling may be indicated. Table 2 provides additional resources to familiarize users with genetic terminology, offer interactive videos and case studies, and provide information about specific genetic diseases.

TYPES OF GENETIC TESTING

There are two main types of genetic testing: genetic tests available through health care providers and DTC genetic testing. Genetic testing through health care providers involves both salivary and blood samples that are sent to specialized laboratories for analysis. A health care professional provides interpretation of test results and a referral for genetic counseling, if applicable. The cost for this testing may range from $300 to $3,000, but insurance coverage may be available. With DTC testing, the individual collects his or her own sample and mails it to a company for analysis. Results are sent back to the individual, and in some cases, a counselor or health care provider may be available by phone or online to answer questions. The cost for DTC testing ranges from $100 to $1,000 and it is not covered by insurance.

In 2016, the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics published a statement recommending that DTC genetic tests should be accredited by the Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments (CLIA), which ensures the testing adheres to strict guidelines.12 Not all DTC tests are CLIA accredited.13 The report also provides guidance on genetic counseling for the public, informs consumers that test results can neither confirm nor rule out the possibility of a disease, and discusses protection of privacy issues regarding results. A privacy disclosure should include who will have access to results and whether test results will impact long-term care or disability insurance.12

CONSIDERATIONS ABOUT GENETIC TESTING

As genetic testing becomes more affordable, consumers can learn more about their propensity toward specific health conditions, be proactive about their care, and share information with health professionals.14 For those diagnosed with a genetic condition, genetic testing can help improve medical management and offer more information about prognosis and preventive treatment.15 For some individuals, genetic testing provides a psychosocial benefit of supporting the validity of the diagnosis, as well as offering a support system through genetic disease organizations and counseling.15 Others may find that there are additional costs as further genetic testing may be needed to define genetic links and for the treatment of the disease.16 In the process of undergoing genetic testing, family members may learn unexpected information or incidental results concerning disease susceptibility, or they might learn they are carriers of a genetic disease. These findings may lead to unexpected psychosocial issues that require additional levels of counseling and support.15 Although an individual may present with a genotype for a disease, this does not necessarily mean he or she will actually get the disease.9

Consumers need to understand that completing genetic testing does not imply that results are completely private. The Genetics Information and Nondiscrimination Act (GINA) of 2008 was enacted to prevent genetic testing discrimination in health coverage and employment.20 However, GINA does not cover genetic discrimination for long-term care facilities, life insurance, and disability insurance. GINA also does not prohibit health insurance companies from obtaining and using genetic information to determine insurance premiums. GINA does not apply to veterans, members of the military, individuals using Indian Health Services, and federal employees enrolled in Federal Employees Health Benefits programs.20

Informed consent is ambiguous when using DTC companies. For example, some companies ask for consumers to sign a brief consent form to participate in their health research programs. If the consumer signs, his or her DNA results can be used in future research and viewed by a third party, with the possibility of producing a genetic commodity for pharmaceutical companies, hospitals, or the government.21

Another aspect to consider is property rights to excised tissues for commercial use. Historically, the courts have ruled that when surgery is performed, excised biological specimens—such as the appendix, moles, drawn blood, etc—are no longer part of the body, so the owner does not have rights to the removed tissue. The tissues become experimental samples for the study of diseases and development of new drugs.22,23 Sometimes cell lines developed from these tissues have great commercial value.22 While it is difficult to refute that human tissue collection is important for genetic and medical research, opponents argue that patients should have control of their tissues and permission should be obtained before experimental use.

FUTURE APPLICATIONS

Recent advances in genetic testing and salivary diagnostic aids have enabled the creation of noninvasive, inexpensive, easy-to-use chairside genetic tests for use in the dental setting. Salivary diagnostic testing may have a future role in diagnosing Sjögren syndrome, cystic fibrosis, cardiovascular disease, diabetes, human immunodeficiency virus, oral cancer, caries, and periodontal diseases.24 Salivary diagnostic kits designed to detect genetic links to periodontal diseases—mainly through variations on the immune and inflammatory marker interleukin (IL)—as well as the presence of oral humanpapilloma virus, are now available. Individuals with mutations in genes with IL-1 and IL-6 may have a genetic susceptibility to periodontal diseases.25 However, the American Dental Association recently published a summary of evidence that found “a predictive test for dental caries or for periodontal disease does not currently exist; both of these are complex diseases with multiple gene and environmental risk factors.”26

Oral health professionals may want to consider creating a handout with genetic resources and genetic counselors for patients who test positive with salivary diagnostics. Informed consent would need to be changed to reflect this type of genetic testing and include GINA guidelines. The development of pharmacogenetics is a promising future as customized drug and adjunctive therapies for oral cancer, periodontal diseases, and caries based on an individuals’ genetic profiles would be possible.

CONCLUSION

Genetics is a rapidly advancing field that both consumers and health care professionals are utilizing. Oral health professionals need to become educated on this topic, so they can effectively inform their patients regarding pros and cons of such testing. Incorporating a three-generational family history and chairside genetic testing expands the framework of dental hygiene practice and offers dental hygienists the opportunity to provide comprehensive care on a different level. As a result, dental hygienists may engage with other health care providers and patients in relating oral health, genetic, and systemic connections. Genetics in oral health care may provide an additional avenue for customizing preventive care and treatment to truly make a difference in patients’ lives.

REFERENCES

- Caulfield T, Evans J, McGuire A, et al. Reflections on the cost of “low-cost” whole genome sequencing: Framing the health policy debate. PLoS. 2013;11:1–6.

- National Institute of Health RePORT. Human Genome Project. Available at: report.nih.gov/NIHfactsheets/ViewFactSheet.aspx?csid=45. Accessed August 23, 2017.

- Opal S, Garg S, Jain J, Walia I. Genetic factors affecting dental caries. Aust Dent J. 2015;60:2–11.

- Taba M, Scombatti de Souza SL, Mariguela VC. Periodontal disease: A genetic perspective. Braz Oral Res. 2012;26:32–38.

- Yildiz G, Ermis RB, Calapoglu NS, Celik EU, Turel, GY. Gene-environment interactions in the etiology of dental caries. J Dent Res. 2016;95:74–79.

- Carvalho FM, Tinoco EMB, Deeley K, et al. FAM5C contributes to aggressive periodontitis. PLoS One. 2010;5:1–10.

- Shailza V, Rahul S, Haque SM, Karunathy S, Subramaniam S. Evaluation of CYP1B1 expression, oxidative stress and phase 2 detoxification enzyme status in oral squamous cell carcinoma patients. J Clin Diagn Res. 2017;11:1–5.

- Yu-Fen L, Pei-Zhen Y, Hua-Feng L. Functional polymorphisms in the IL-10 gene with susceptibilitiy to esophageal, nasopharyngeal, and oral cancers. Cancer Biomark. 2016;16:641–651.

- Read A, Donnai D. New Clinical Genetics 3. Banbury: United Kingdom; Scion Publishing Ltd; 2015.

- Collins FS, Green ED, Guttmacher AE, Guyer MS. A vision for the future of genomics research. Nature. 2003;422:835–847.

- National Coalition for Health Professional Education in Genetics. Core Competencies for Health Professionals. Available at: nchpeg.org/ documents/Core_Comps_English_2007.pdf. Accessed August 23, 2017.

- American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics Board of Directors. Direct-to-consumer genetic testing: A revised position statement of the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics. Gent Med. 2016;18:207–208.

- Hudson K Javitt G, Burke W, Byers P, ASHG Social Issues Committee. ASHG Statement on Direct-to-Consumer Genetic Testing in the United States. Am J Hum Genet. 2007;81:635–637.

- Darst BF, Madlensky L, Schork NJ, Topol EJ, Bloss CS. Characteristics of genomic test consumers who spontaneously share results with their health care provider. Health Commun. 2014;29:105–108.

- Cohen J, Hoon A, Floet AMW. Providing family guidance in rapidly shifting sand: Informed consent for genetics testing.Dev Med Child Neurol. 2013;55:766–769.

- Severin F, Borry P, Cornel MC, et al. Points to consider for prioritizing clinical genetic testing services: A European consensus process oriented at accountability for reasonableness. Eur J Hum Genet. 2013;23:729–735.

- Hawkins AK, Ho A. Genetic counseling and the ethical issues around direct to consumer genetic testing. J Genet Couns.2012;21:367–373.

- Bloss CS, Wineinger NE, Darst BF, Schork NJ, Topol EJ. Impact of direct-to-consumer genomic testing at long term follow-up. J Med Genet. 2013;50:393–400.

- Kaufman DJ, Bollinger JM, Dvoskin RL, Scott JA. Risky business: Risk perception and the use of medical services among customers of DTC personal genetic testing. J Genet Couns. 2012;21:413–422.

- United States Department of Health and Human Services. Genetics Information and Nondiscrimination Act. Available at: genome.gov/24519851/. Accessed August 23, 2017

- Murphy E. Inside 23 and me founder Anne Wojcicki’s $99 DNA revolution. Fast Company. Available at: fastcompany.com/3018598/for-99-this-ceo-can-tell-you-what-might-kill-you-inside-23andme-founder-anne-wojcickis-dna-r. Accessed August 23, 2017.

- Moore v Regents of University of California, 793 P2d 479 (California 1990).

- Allen MJ, Powers MLE, Gronowski KS, Gronowski AM. Human tissue ownership and use in research. What laboratorians and researchers should know. Clin Chem. 2010;56:1675–1682.

- Mohammad JA, Ahad SA, Durand R, Tran SD. Saliva as a diagnostic tool for oral and systemic disease. J Oral Biol Craniofac Res. 2016;6:66–75.

- Taba M, Scombatti de Souza SL, Mariguela VC. Periodontal disease: a genetic perspective. Braz Oral Res. 2012;26:32–38.

- American Dental Association Council on Scientific Affairs. Genetics and Oral Health. Available at: ada.org/en/member-center/oral-health-topics/genetics-and-oral-health?source=VanityURL. Accessed August 23, 2017.

- Johnson L, Genco RJ, Damsky C, et al. Genetics and its implications for clinical dental practice and education. J Dent Educ. 2008;72:86–94.

- Domingue B, Conley D, Fletcher J, Boardman J. Cohort effects in the genetic influence on smoking. Behav Genet. 2016;46:31–42.

Featured photo by NATALI_MIS/ISTOCK/GETTY IMAGES PLUS

From Dimensions of Dental Hygiene. September 2017;15(9):32-36.