This course was published in the May 2013 issue and expires May 2016. The authors have no commercial conflicts of interest to disclose. This 2 credit hour self-study activity is electronically mediated.

EDUCATONAL OBJECTIVES

After reading this course, the participant should be able to:

- Identify the concepts of basic emergency management.

- List the components of an up-to-date emergency kit.

- Explain how to address the most common medical emergencies in the dental office.

Medical emergencies that occur in dental offices can vary from minor to life threatening. All dental team members need to be prepared to take an active role in handling an emergency. Each staff person should be able to perform basic life support services competently in order to keep patients alive until advanced help arrives. The most prepared dental offices routinely practice various scenarios and employ a team approach to handle any acute emergency. Every dental office should have an emergency management plan in place.1

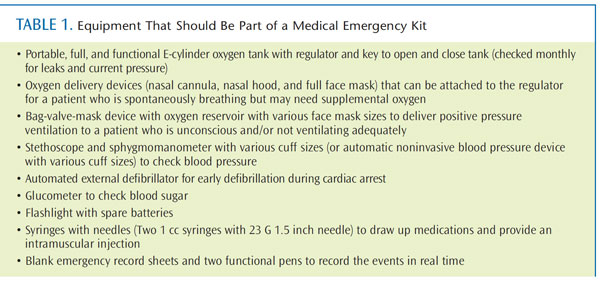

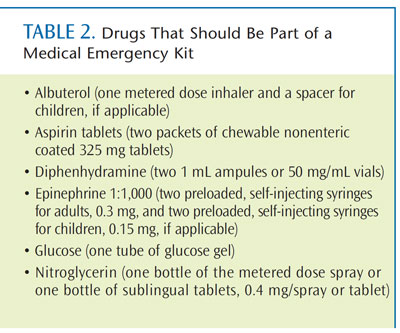

EMERGENCY KIT

All dental offices should have an up-to-date basic emergency kit available at all times. Table 1 and Table 2 provide a list of the equipment and drugs needed in an emergency kit (state regulations should be checked for any additional requirements). Proprietary kits can be purchased from a variety of manufacturers. An assigned staff member must be responsible for ensuring the kit and oxygen tank are viable and that the drugs have not expired.

BASIC MANAGEMENT

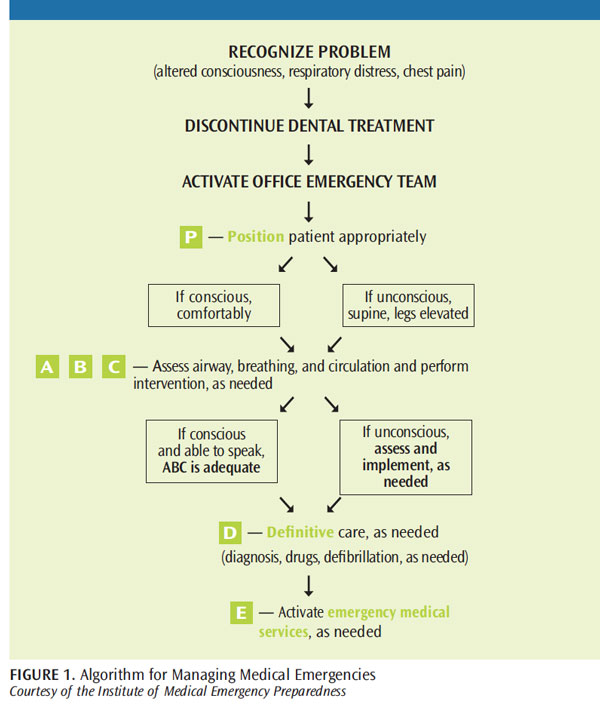

The basic algorithm shown in Figure 1 should be followed for the management of all medical emergencies. Assess airway (A), breathing (B), and circulation (C). The American Heart Association recently changed the order of this algorithm to CAB—circulation, airway, and breathing—for cardiac arrest only. The original ABC should be followed for basic medical emergencies. All patients should undergo a thorough medical history review and have their vital signs recorded before treatment begins. Promptly recognizing an emergency followed by quick response are imperative to successful outcomes.

There are two main positions that patients can be placed in when they are experiencing a medical emergency. If the patient remains conscious, he or she should choose whether to sit upright or recline. If the patient loses consciousness, he or she should be placed supine or in the head down/feet up (Trendelenburg) position. Low blood pressure in the brain is the cause of almost all medical emergencies where the patient loses consciousness. Making the patient supine increases blood pressure in the brain and will help the patient regain consciousness in most cases. Medical emergency care should be administered by the dental team members based on their training and ability. However, all dental personnel should be familiar with the basic emergency kit and common medical emergencies. Keeping up-to-date with continuing education courses, literature, and basic life support training is critical for proper preparation.

Calling emergency medical services (EMS) is not always necessary, but it is never wrong. Regardless of the situation, EMS personnel have advanced training and equipment and dental staff should not hesitate to call them at any point during a perceived medical emergency. The prompt recognition and efficient management of medical emergencies by a well-prepared dental team can increase the likelihood of a satisfactory outcome.2 Following are some of the more common medical emergencies encountered in the dental office.

VASOVAGAL SYNCOPE

Fainting or vasovagal syncope is the most common medical emergency seen in the dental office,3 and is most often caused by anxiety. For some patients, assuaging anxiety only requires that dental hygienists explain each procedure in more detail. Others may require different levels of sedation—ranging from nitrous oxide/oxygen to general anesthesia—to properly address their anxiety.

When a patient experiences syncope, he or she should be placed in a head down/feet up position and the ABCs must be assessed. Most patients with syncope have a patent airway, are breathing, demonstrate an adequate pulse, and respond to positional changes within 30 seconds to 60 seconds. If the patient does not respond in this timeframe, he or she did not simply faint and the dental team must consider a more complete differential diagnosis for loss of consciousness.

Although many possible explanations exist, the more common reasons include low glucose levels, stroke, or cardiac arrest. In each of these examples, the initial management of the emergency situation is the same. The dental hygienist should recognize the event, call for help and the emergency kit, and place the patient in a head down/feet up position. The patient’s airway should be opened with a head-tilt/ chin lift and breathing assessed. If the patient is breathing, the next step is to check circulation and record the patient’s vital signs. Does the patient have a palpable pulse at the carotid artery? What is the patient’s pulse rate and blood pressure? If he or she has not responded within 1 minute, the clinician probably can rule out vasovagal syncope.

Patients who are breathing spontaneously/normally may be experiencing hypoglycemia, or stroke, but not cardiac arrest. In cardiac arrest, the patient does not adequately breathe spontaneously. A patient who is not breathing or not breathing adequately requires positive pressure ventilation with 100% oxygen, which is most often performed with a bag-valve-mask (BVM) device plugged into an E-cylinder portable oxygen tank (Figure 2). Immediate activation of EMS is critical.

Patients placed in a supine position who do not regain consciousness within 60 seconds, but are breathing spontaneously, are likely experiencing hypoglycemia or stroke. If the patient’s blood pressure is normal, low glucose level is most likely the problem. If the patient’s blood pressure is alarmingly high, he or she may be having a stroke. Both of these scenarios require the urgent contact of EMS.

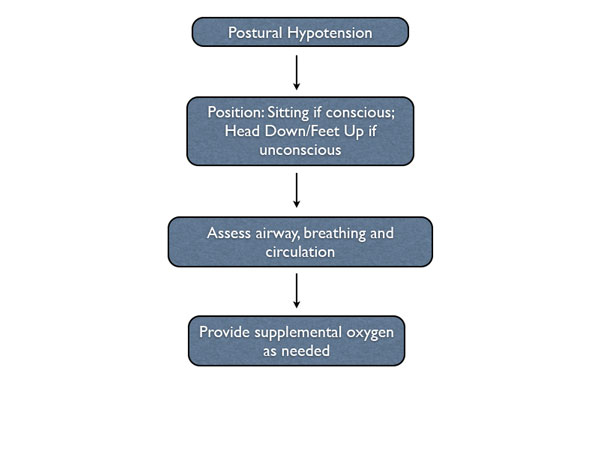

POSTURAL HYPOTENSION

Postural hypotension occurs when a patient stands up too quickly and his or her blood supply is pooled in the lower extremities. This can cause the patient to feel dizzy or lose consciousness due to the lack of blood and oxygen to the brain. In this situation, the patient needs to sit back down. If he or she has lost consciousness, follow the algorithm for syncope by placing the patient in a head down position until consciousness is regained. Ensuring that the patient sits up slowly and waits at least a few minutes before standing can prevent this medical emergency.

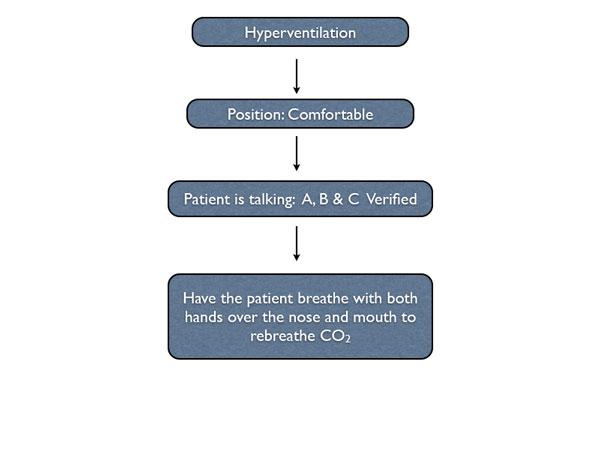

HYPERVENTILATION

Hyperventilation happens when the patient is breathing too quickly, which in the dental setting, is most often caused by anxiety. This rapid breathing pattern causes the patient to blow off too much carbon dioxide (CO2), changing his or her physiologic pH and producing an altered level of consciousness. The first step is to recognize the condition and calmly inform the patient. Most often, the patient is unaware of how fast he or she is breathing. Position the patient comfortably, usually sitting upright.

Because the patient is conscious and talking, ABC has been verified. The patient should be reassured and instructed to breath with both hands over the nose and mouth in an attempt to rebreathe CO2. Supplemental oxygen is not indicated for this condition. Once the situation is stable, the dentist or dental hygienist should discuss the patient’s dental anxiety in order to prevent another episode in the future.

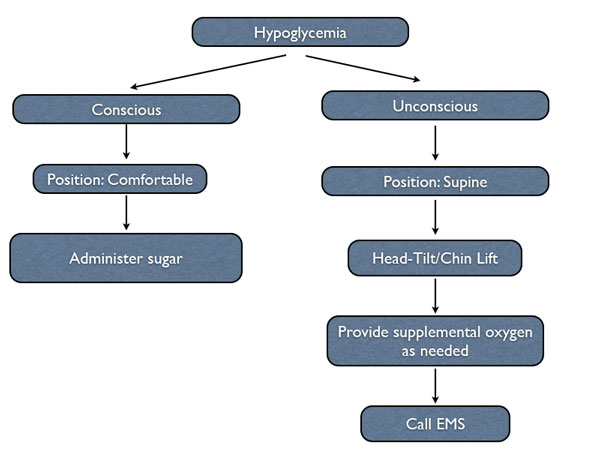

HYPOGLYCEMIA

Patients who experience hypoglycemia often have a history of diabetes. Patients with type 1 diabetes (and some with type 2) self-administer insulin to decrease a high glucose level (hyperglycemia) toward the upper limit of normal (120 milligrams/deciliter). Patients with diabetes must ingest food soon after administering insulin to prevent the development of hypoglycemia. The most common cause of hypoglycemia among patients with type 1 diabetes is failing to eat after administering insulin.

Patients who experience hypoglycemia often have a history of diabetes. Patients with type 1 diabetes (and some with type 2) self-administer insulin to decrease a high glucose level (hyperglycemia) toward the upper limit of normal (120 milligrams/deciliter). Patients with diabetes must ingest food soon after administering insulin to prevent the development of hypoglycemia. The most common cause of hypoglycemia among patients with type 1 diabetes is failing to eat after administering insulin.

Patients with clinically significant hypoglycemia commonly experience sweating, rapid heart rate, and feeling faint. Subsequently, they may experience mental confusion and loss of consciousness. As long as the patient retains consciousness, he or she should remain in a comfortable position. Conscious patients with hypoglycemia have a patent airway, are breathing, and have an adequate pulse. The treatment of choice is the administration of sugar. Unconscious patients with hypoglycemia require parenteral administration of sugar, which necessitates EMS. Dental professionals should never place any liquid or substance that might become a liquid at body temperature into the mouth of an unconscious patient as this can cause choking.4

LOCAL ANESTHETIC OVERDOSE

Systemic toxicity attributed to local anesthetics is dose dependent. As local anesthetics are absorbed from the injection site, their concentration in the blood stream rises and the peripheral and central nervous systems are depressed in a dose-dependent manner. Higher concentrations induce seizure activity, which can be life-threatening. As serum concentrations continue to rise further, coma, respiratory arrest, and, eventually, cardiovascular collapse occurs.5

Peak serum level occurs 20 minutes to 30 minutes following injection of lidocaine. Regardless of the route of administration, peak levels are reduced and the rate of absorption is delayed by adding epinephrine 1:200,000 or greater to the local anesthetic solution. One can reasonably conclude that adhering to published maximum recommended dosages for local anesthetics will not result in systemic serum levels that approach those associated with toxicity.

Scott et al found the dosage and speed of injection were directly related to serum concentration. 6 A solution’s concentration (eg, 2% versus 4%) was not relevant; serum concentrations were related to the total dosage. Administering 20 mL of 2% or 10 mL of 4% produced the same serum concentration. When using lidocaine or other anesthetics, regardless of their formulated concentration, the dosage (milligrams) administered must be considered, not the volume (milliliters or cartridges). Management of a local anesthetic overdose is based on the severity of the reaction. In most cases, the reaction is mild and transitory, requiring little or no specific treatment.7 In other instances, it may be more severe and longer lasting, in which case prompt therapy is necessary. Most local anesthetic overdoses are self-limiting because the blood level in the target organ causing the overdose—the brain—continues to decrease as time progresses and redistribution occurs. Only rarely are drugs necessary to terminate a local anesthetic overdose.

Signs and symptoms of a mild overdose are retention of consciousness, talkativeness, and agitation, along with increased heart rate, blood pressure, and respiratory rate usually developing between 5 minutes and 10 minutes after completion of the anesthetic injection(s). If a local anesthetic overdose is suspected, position the conscious patient comfortably and assess ABC (adequate if patient is conscious and talking). Reassure the patient while administering oxygen via nasal cannula or nasal hood. Monitor and record vital signs.7 If the patient loses consciousness, activate EMS and begin basic life support.

ANAPHYLAXIS

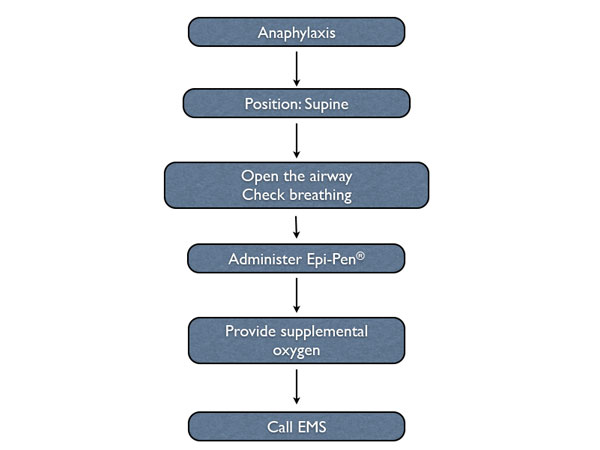

Anaphylaxis is a severe form of allergy. If the patient exhibits either respiratory (difficulty breathing, wheezing) or cardiovascular (blood pressure drop, dizziness) symptoms during an allergic reaction, the allergy is severe and may be termed anaphylaxis. Anaphylaxis is an acute life-threatening systemic reaction with varied mechanisms and clinical presentations.8 Immediate discontinuation of the offending allergen and early administration of epinephrine are the cornerstones of treatment. Epinephrine is the drug of choice in the treatment of anaphylaxis, based on its receptor pharmacology. Epinephrine’s alpha-1 agonistic effects cause systemic vasoconstriction, which raises blood pressure. Epinephrine’s beta-1 agonistic effects increase heart rate, force of contraction, stroke volume, and cardiac output, which are all important in the treatment of anaphylaxis. Finally, epinephrine’s beta-2 agonistic effects provide bronchial smooth-muscle relaxation and resultant bronchodilation.9 Absorption is more rapid and plasma levels are higher in patients who receive epinephrine intramuscularly in the thigh with an autoinjector.10 Intramuscular injection into the thigh or vastus lateralis muscle is superior to intramuscular or subcutaneous injection into the arm or deltoid muscle.11

If the allergy is severe, the patient will lose consciousness. The dental team should place the patient in a supine position, open the airway, and evaluate breathing. If the patient is not breathing, or not breathing adequately, the dental team must administer positive pressure oxygen via a BVM device. If the patient has lost consciousness, his or her cerebral blood pressure is too low. The patient’s systemic blood pressure will also become dangerously low. EMS should be activated immediately. In addition to cardiovascular and respiratory collapse, there can be significant airway edema that needs to be aggressively and quickly treated by EMS.

SUMMARY

Dental hygienists should maintain basic life support skills and understand emergency protocols so they are confident in their ability to handle emergencies. Regular practice sessions and an updated emergency kit also help to ensure a well-equipped and prepared dental office and staff, which promotes patient safety.

Steps to take when a patient experiences postural hypotension in the dental office.

Steps to take when a patient experiences hyperventilation in the dental office.

Steps to take when a patient experiences hypoglycemia in the dental office.

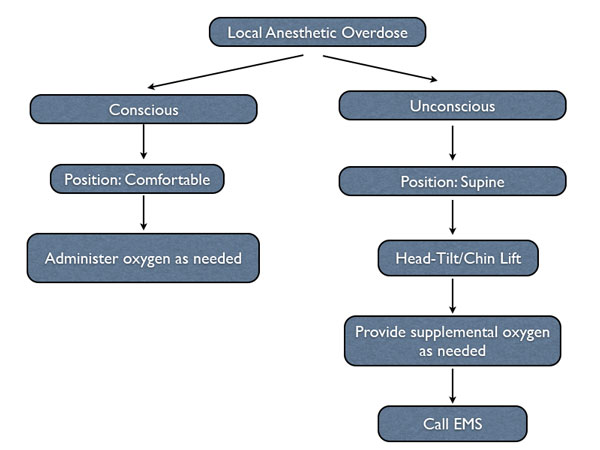

Steps to take when a patient experiences a local anesthetic overdose in the dental office.![]()

Steps to take when a patient experiences anaphylaxis in the dental office.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

FIGURE 2 REPRINTED WITH PERMISSION FROM: MALAMED SF. MEDICAL EMERGENCIES IN THE DENTAL OFFICE. 6TH ED. ST. LOUIS: MOSBY; 2007.

REFERENCES

-

- Haas DA. Preparing dental office staff members for emergencies: developing a basic action plan. J AmDent Assoc. 2010;141(Suppl):8S–13S.

- Reed KL. Basic management of medical emergencies. J Am Dent Assoc.2010;141(Suppl):20S–24S.

- Findler M, Elad S, Garfunkel A, et al. Syncope in the dental environment. Refuat Hapeh Vehashinayim.2002;19:27–33, 99.

- Malamed SF. Medical Emergencies in the DentalOffice. 6th ed. St. Louis: Mosby; 2007:283.

- Becker DE, Reed KL. Local Anesthetics: review of pharmacological considerations. Anesth Prog.2012;59:90–103.

- Scott DB, Jebson PJ, Braid DP, Ortengren B, Frisch P.Factors affecting plasma levels of lignocaine and prilocaine. Brit J Anaesth. 1972;44:1040–1049.

- Malamed SF. Handbook of Local Anesthesia. 6thed. St. Louis: Mosby; 2013.

- Joint Task Force on Practice Parameters; AmericanAcademy of Allergy, Asthma and Immunology;American College of Allergy, Asthma and Immunology; Joint Council of Allergy, Asthma and Immunology. The diagnosis and management of anaphylaxis: An updated practice parameter. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2005;115(Suppl):S483–S523.

- Hepner DL, Castells MC. Anaphylaxis during the perioperative period. Anesth Analg. 2003;97:1381–1395.

- Simons FER, Roberts JR, Gu X, Simons KJ.Epinephrine absorption in children with a history of anaphylaxis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1998;101:33–37

- Simons FER, Gu X, Simons KJ. Epinephrine absorption in adults: intramuscular versus subcutaneous injection. J Allergy Clin Immunol.2001;108:871–873.

From Dimensions of Dental Hygiene. May 2013; 11(5): 48–51.