An Individualized Approach to Peri-Mucositis Prevention

Oral health professionals well versed in effective diagnostics and prevention strategies can help patients avoid this precursor to peri-implantitis.

Peri-implantitis and peri-implant disease are nonspecific terms for infection or inflammation around a dental implant, which can affect surrounding soft and hard tissue. As such, these conditions warrant more specific terminology, identification, and action.1,2 Peri-implant mucositis occurs when inflammation is present in the mucosa surrounding the dental implant with no sign of supporting bone loss, as it most often precedes bone loss.3 True peri-implantitis occurs when inflammation spreads from the soft tissue to the underlying bone, causing bone loss. Roos-Jansaker et al4 report that peri-implant mucositis occurs in 48% of implants 9 years to 14 years post-surgery. Oral health professionals can make a significant difference in the health of patients with peri-mucositis by arresting the disease process; thus, preventing the loss of surrounding bone.5

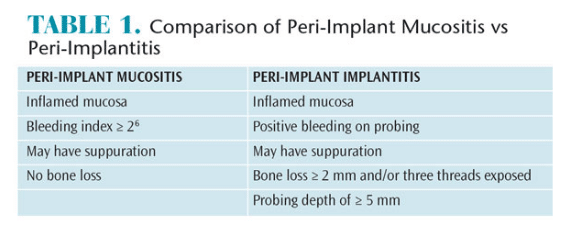

Clinical signs of peri-implant mucositis are similar to periodontitis. As underlying vessels dilate and become engorged with blood, the soft tissue color changes from pale pink to deep red, or bluish. Interdental papillae appear blunted; the gingival margin may present as a rolled or thickened margin instead of a healthy knife-edged margin (Figure 1). Bleeding on probing or even spontaneous bleeding may accompany visible soft tissue inflammation. Table 1 provides a comparison between peri-implant mucositis and peri-implantitis.6

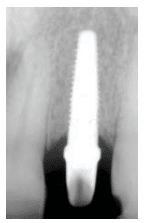

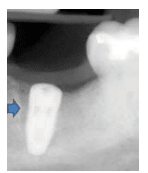

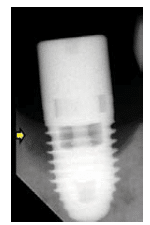

Peri-implant mucositis has a very similar clinical presentation to peri-implantitis (Figure 2). Assessing inflammation around a dental implant, while differentiating between peri-implant mucositis and peri-implantitis, requires a combination of diagnostic tools. To identify mucositis, peri-implant inflammation must first be identified and then radiography is used to rule out bone loss.7 Radiographs of a patient with peri-mucositis will not show any radiolucent areas surrounding the implant.

A baseline radiograph should be used as a reference when identifying bone loss. Unfortunately, such an image is often not available. Another option is to use a threshold vertical distance of 2 mm from the expected marginal bone level following the expected post-placement related remodeling (Figure 3). Subtraction programs are available to define radiographic changes in digital images. In the absence of such programs, radiographs taken perpendicular to the implant showing clear thread demarcation can be compared across time points to identify bone loss.

DIAGNOSTIC METHODS

Probing is a necessary diagnostic tool in assessing periodontal or peri-implant health. Probing with light force protects adjacent soft tissue. Plastic periodontal probes help prevent scratching of the implant surface, which can create irregularities, enabling plaque to accumulate. Probing depth is defined as the distance from the base of the sulcus/pocket around the implant to the crest of the soft tissue. Because identifying increasing probing depths can be helpful to early diagnosis, a comparison to baseline probing (when the final restoration is placed) is useful. As a rough rule, clinical examination probing depths greater than 5 mm are associated with peri-mucositis. Bleeding and suppuration indicate the need for further evaluation to rule out peri-implant disease.7 A clinical finding of bleeding on probing or suppuration, however, cannot be used to distinguish between mucositis and implantitis. These findings suggest the need for further diagnostics such as radiographic evaluation for bone loss.

Peri-implant disease diagnostics are a vastly expanding area of study. A recent meta-analysis reported that peri-implant crevicular fluid is useful in identifying infection.8 Crevicular fluid contains inflammatory mediators, such as interleukin (IL)-1? and tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-?, that are present in different concentrations in healthy tissue vs tissue with peri-mucositis vs peri-implant bone loss. Another expanding area of research involves identifying genetic markers for peri-implantitis diagnosis. Although this is not ready for chairside application, genetic marker identification shows promise for the future.9 Culture, direct microscopy immunoserological identification, and nucleic acid-based methods may be performed to ascertain the microbial species responsible for triggering inflammation. Clinical oral microbiology laboratories employ one or a combination of these methods, depending on the pathogens that need to be identified. Rarely does one detection method prove optimal for all situations.

PATHOGENESIS

Although the tissues surrounding an implant are not contiguous with a periodontal ligament, peri-implant mucositis is histologically and anatomically similar to gingivitis. Peri-implant mucositis is also reversible as is gingivitis. The bacterial biofilm that triggers gingivitis also initiates peri-implant mucositis. Similar to natural teeth following a dental prophylaxis, the exposed titanium surfaces of a newly placed dental implant accumulate sticky glycoproteins and form a salivary pellicle. Microbial colonization begins and develops into a biofilm.10 The biofilm development is also similar. Initial colonizers are Gram-positive aerobic coccus bacteria, but as the biofilm develops, there is a shift toward Gram-negative anaerobic bacteria. Unlike gingivitis around natural teeth in the pathogenesis of periodontitis, studies have suggested that the Staphylococcus species—not normally found proximate to natural teeth—may play a role in peri-implant diseases.4,11

In peri-implant mucositis, just as in gingivitis, bacterial biofilm triggers a similar host immune response. In both conditions, as soft tissue inflammation progresses, blood vessels adjacent to the pocket epithelium become enlarged and more permeable. Increased vessel permeability causes neutrophils to migrate out of the vessels into the pocket area. Collagen surrounding the blood vessels is broken down. Lymphocytes and macrophages accumulate in the newly created space. Fibroblasts show pathologic changes, and collagen is lost apical to the pocket epithelium. Histologic evaluation shows the underlying connective tissue adjacent to the pocket epithelium exhibits more B-lymphocytes, which subsequently transform into plasma cells.12 The ever deepening pocket creates a reservoir to retain bacteria, and pH and redox characteristics provide favorable conditions. The products of these pathogens further challenge the host immune defense, as underlying connective tissue continues to hydrolyze, deepening the pocket in an apical direction. At this point, the condition has progressed from mucositis to peri-implantitis and supporting bone is also broken down.2,13

The rate of progression to the supporting bone is often faster in peri-implantitis compared to periodontitis.14 This further highlights the importance of early detection and prevention in implant cases. Structural differences between periodontal and peri-implant tissues account for this. Unlike natural teeth, dental implants do not have cementum or Sharpey’s fibers and are not bounded by a periodontal ligament. Bone contacts the implant surface directly in an osseointegrated implant. As such, the pathway of inflammation goes directly from the soft tissue to the hard tissue without first encountering ligamentous structures or cementum. When the inflammatory process encounters the dentogingival fibers and periodontal ligament fibers, attachment apparatus is lost through the action of collagenases. In the case of peri-implantitis, the periodontal ligament is missing, so inflammation progresses directly to the bone. Eventually in both conditions, the inflammatory process reaches the alveolar bone crest and osteoclastic bone resorption occurs. The inflammatory cells activate cytokines such as IL-1, TNF-?, and IL-6.15

Just as the primary objective to treat gingivitis is to remove plaque bacterial biofilm from the tooth surface, so too it is in peri-implant mucositis. And just as the prevention of gingivitis stems from interrupting biofilm accumulation, identifying and removing plaque retentive sites around dental implants are also crucial to the prevention of peri-mucositis.

ORAL HYGIENE INSTRUCTION

Peri-implant mucositis is reversible by removing plaque bacterial biofilm, which triggers the inflammatory cascade.16 Any factors that contribute to poor plaque control or plaque retention increase the risk for peri-implant mucositis. Patients’ lack of compliance with oral hygiene is the most obvious cause, but further investigation is warranted. Mental or physical disabilities may preclude adequate oral hygiene. In the case of physical disability, providing mechanical toothbrush recommendations may be helpful.17,18 In the case of a more compromised patient, providing instructions to the caregiver or case manager may be useful. There is a significant evidence base of controlled, prospective studies that provide information about the efficacy of various dentifrices and mouthrinses around implants.19 Judging from the similar pathogenesis between gingivitis and peri-implant mucositis, toothpastes containing either stannous fluoride or triclosan with a copolymer have statistically significant antiplaque and antigingivitis activity.20 Similarly, investigation into stannous fluoride-sodium hexametaphosphate toothpaste showed a high level of antiplaque and antigingivitis activity.21,22

A previous history of periodontitis is also associated with peri-implant inflammation. Soft tissues isolated from patients with a history of periodontal disease show greater periopathogens and superinfecting bacteria compared to control patients.23 Prospective studies demonstrate that patients with generalized aggressive periodontitis are more susceptible to peri-implantitis. Based on these and other studies, a history of periodontitis warrants more vigilant screening when preventing peri-implant mucositis.24

RISK ASSESSMENT

Patients presenting with conditions or habits, such as smoking, that inhibit the body’s mechanisms to fight off bacterial insult are also at increased risk of peri-implantitis.25,26 Conditions that contribute to systemic inflammation can exacerbate local inflammation around implants. Diabetes is the most familiar of these maladies; poor glycemic control appears to aggravate peri-implant diseases. This is likely because elevated blood glucose impairs host defenses and neutrophilic functions.27 As such, when the initial plaque bacterial biofilm insult occurs, the host is less capable of maintaining homeostasis. Similarly, genetic factors such as the IL-1 gene polymorphism may be a risk factor,22 but the research is unclear.26 Chronic inflammatory diseases, such as rheumatoid arthritis that exacerbate local inflammation triggered by biofilm insult, appear to be risk factors in peri-implantitis.26

Broken or poorly designed prosthetics or substandard nearby tooth restorations may interfere with oral hygiene measures. One way to identify a plaque-retentive restoration is to look for areas that catch impression material while taking routine models. Additionally, loose restorative components create space for pellicle adhesion and trigger the start of the inflammatory cascade leading up to peri-implant mucositis. Referral to a dentist may begin the process of addressing these plaque retentive factors. However, there are no randomized clinical trials that directly prove crown design is linked to peri-implant mucositis.28,29 Excess cement that remains in place following crown placement not only directly irritates surrounding mucosa, but also contributes to poor plaque control. The rough surface of cement accumulates plaque bacterial biofilm and promotes biofilm proliferation.30 In addition to targeted cement removal, restorations—such as screw retained crowns—can be strategically planned to minimize this risk.

Frank occlusal overloading or excessive off-axis (tipping force) loading may contribute to peri-implant risk. Occlusal loading of implants appears concentrated at the bony crestal areas.31,32 There is also evidence to suggest that overloading and poor oral hygiene may be co-factors that contribute to bone loss around implants.33

PREVENTIVE INTERVENTION

Because peri-implantitis can progress faster than typical periodontitis, prevention and early detection and treatment of peri-implant mucositis and peri-implantitis are seminal to optimal outcomes. As the underlying molecular mechanisms of peri-implantitis are not well understood, preventive intervention cannot rely solely on toothpastes and mouthrinses. Disrupting the causative plaque bacterial biofilm from the implant surface can reverse the effects of peri-implant mucositis and prevent disease progression.1 Mechanical scaling and root planing has been shown to successfully reverse peri-implant mucositis.34 Although laser therapy has been investigated, its superiority over conventional means has not been established.35 In addition, the use of local delivery and systemic antibiotic therapy as adjuncts to mechanical plaque removal has shown limited success.36 Pathogenic bacteria have been noted to be resistant to various antibiotics such as clindamycin, amoxicillin, metronidazole, and doxycycline.37 Oral health professionals who note the signs and symptoms of peri-implant diseases early and individualize treatment strategies are best prepared to help their patients to optimize their periodontal health.

REFERENCES

- Mombelli A, Lang NP. The diagnosis and treatment of peri-implantitis. Periodontol 2000. 1998;17:63-76.

- Lindhe J, Meyle J; Group D of European Workshop on Periodontology. Peri-implant diseases: Consensus report of the Sixth European Workshop on Periodontology. J Clin Periodontol. 2008;35(8 Suppl):282–285.

- American Academy of Periodontology. Glossary of Periodontal Terms. Available at: perio.org/sites/default/files/files/PDFs/Publications/GlossaryOfPeriodontalTerms2001Edition.pdf. Accessed September 30, 2015.

- Roos-Jansaker AM, Lindahl C, Renvert H, Renvert S. Nine- to fourteen-year follow-up of implant treatment. Part II: presence of peri-implant lesions. J Clin Periodontol. 2006;33:290–295.

- Sanz M, Chapple IL. Clinical research on peri-implant diseases: consensus report of working group 4. J Clin Periodontol. 2012;39(Suppl 12):202–206.

- Atieh MA, Alsabeecha NHM, Faggion Jr CM, Duncan WJ. The frequency of peri-implant disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Periodontol. 2013;84:1586–1598.

- Albrektsson T, Dahl E, Enbom L, et al. Osseointegrated oral implants. A Swedish multicenter study of 8139 consecutively inserted Nobelpharma implants. J Periodontol. 1988;5:287–296.

- Faot F, Nasciemento GG, Bielemann AM, Campao TD, Leite FR, Quirynen M. Can peri-implant crevicular fluid assist in the diagnosis of peri-implnatitis? A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Periodontol. 2015;86:631–645.

- Hall J, Britse AO, Jemt T, FribergB, A controlled clinical exploratory study on genetic markers for peri-implnatitis. Eur J Oral Implantol. 2011;4:371–382.

- Van Dyke TE, van Winkelhoff AJ. Infection and inflammatory mechanisms. J Clin Periodontol. 2013;84:1–7.

- Zitzmann NU, Berglundh T. Definition and prevalence of peri-implant diseases. J Clin Periodontol. 2008;35:286–291.

- Marchetti, C, Farina A, Cornaglia AI. Microscopic, immunocytochemical and ultrastructual properties of peri-implant mucosa in humans. J Periodontol. 2002;73:555–563.

- Lang NP, Berglundh T. Peri-implant diseases: Where are we now? Consensus of the Seventh European Workshop on Periodontology. J Clin Periodontol. 2011:38(Suppl. 11):178–181.

- Schou S, Holmstrup P, Reibel J, Juhl M, Hjorting-Hansen E, Kornman KS. Ligature-induced marginal inflammation around osseointegrated implnats and ankylosed teeth: Stereologic and histologic observations in cynomolgus monkeys. J Periodontol. 1993;64:529–537.

- Lindhe J, Berglundh T, Ericsson I, Liljenberg B, Marinello C. Experimental breakdown of peri-implant and periodontal tissues. A study in the beagle dog. Clin Oral Implants Res. 1992;3:9–16.

- Salvi GE, Aglietta M, Eick S, Sculean A, Lang NP, Ramseier CA. Reversibility of experimental peri-implant mucositis compared with experimental gingivitis in humans. Clin Oral Implants Res. 2012;23:182–190.

- Dentino AR, Derderian G, Wolf M, et al. Six-month comparison of powered versus manual toothbrushing for safety and efficacy in the absence of professional instruction in mechanical plaque control. J Periodontol. 2002;73:770–778.

- Rosema NAM, Timmerman MF, Verseteeg PA, Helderman WH, Van der Velden U, Van der Weijden GA. Comparison of the use of different modes of mechanical oral hygiene in prevention of plaque and gingivitis. J Periodontol. 2008;79:1386–1394.

- Ata-Ali J, Ata-Ali F, Galindo-Moreno P. Treatment of periimplant mucositis: a systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Implant Dent. 2015;24:13–18.

- Gunsolley JC. A meta-analysis of six-month studies of antiplaque and antigingivitis agents. J Am Dent Assoc. 2006;137:1649–1657.

- Mallatt M, Mankodi S, Bauroth K, et al. A controlled 6-month clinical trial to study the effects of a stannous fluoride dentifrice on gingivitis. J Clin Periodontol. 2007;34:762–767.

- Archila L, He T, Winston JL, et al. Antigingivitis efficacy of a stabilized stannous fluoride/sodium hexametaphosphate dentifrice in subjects previously nonresponsive to a triclosan/ copolymer dentifrice. Compend Contin Educ Dent. 2005;26(9 Suppl 1):12–18.

- Botero JE, Gonzalez AM, Mercado RA, et al. Subgingival Microbiota in peri-implant mucosa lesions and adjacent teeth in partially edentulous patients. J Periodontol. 2005;76:1490–1495.

- Swierkot K, Lottholz P, Flores-de-Jacoby L, Mengel R. Mucositis, peri-implantitis, implant success, and survival of implants in patients with treated generalized aggressive periodontitis: 3- to 16-year results of a prospective long-term cohort study. J Periodontol. 2012;83:1213–1225.

- Strietzel FP, Reichart PA, Kale A, Kulkarni M, Wegner B, Kuchler I. Smoking interferes with the prognosis of dental implant treatment: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Clin Periodontol. 2007;34:523–544.

- Clementini M, Rossetti PH, Penarrocha D, Micarelli C, Bonachela WC, Canullo L. Systemic risk factors for peri-implant bone loss: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2014;43:323–334.

- Salvi GE, Carollo-Bittel B, Lang NP. Effects of diabetes mellitus on periodontal and peri-implant conditions: Update on associations and risks. J Clin Periodontol. 2008;35:398-409.

- Belser UC, Bernard JP, Buser D. Implant-supported restorations in the anterior region: prosthetic considerations. Pract Periodontics Aesthet Dent. 1996;8:875–883.

- Brägger U, Hirt-Steiner S, Schnell N, et al. Complication and failure rates of fixed dental prostheses in patients treated for periodontal disease. Clin Oral Implants Res. 2011;22:70–77.

- Wilson TG Jr. The positive relationship between excess cement and peri-implant disease: A prospective clinical endoscopic study. J Periodontol. 2009;80:1388–1392.

- Rungsiyakull C, Rungsiyakull P, Li Q, Li W, Swain M. Effects of occlusal inclination and loading on mandibular bone remodeling: A finite element study. Int J Oral Maxillofac Implants. 2011;26:527–537.

- Stanford CM, Brand RA. Toward an understanding of implant occlusion and strain adaptive bone modeling and remodeling. J Prosthet Dent. 1999;81:553–561.

- Fu JH, Hsu YT, Wang HL. Identifying occlusal overload and how to deal with it to avoid marginal bone loss around implants. Eur J Oral Implantol. 2012;5(Suppl):S91–103.

- Renvert S, Roos-Jansaker AM, Claffey N. Non-surgical treatment of peri-implant mucositis and peri-implantitis: a literature review. J Clin Periodontol. 2008;35(8 Suppl):305–315.

- Kotsakis GA, Konstantinidis I, Karoussis IK, Ma X, Chu H. A systematic review and meta-analysis of the effect of various laser wavelengths in the treatment of peri-implantitis. J Periodontol. 2014;85:1203–1213.

- Esposito M, Grusovin MG, Worthington HV. Treatment of peri-implantitis: what interventions are effective? A Cochrane systematic review. Eur J Oral Implantol. 2012;5 (Suppl):S21–41.

- Rams TE, Degener JE, van Winkelhoff AJ. Antibiotic resistance in human peri-implantitis microbiota. Clin Oral Implants Res. 2014;25:82–90.

From Dimensions of Dental Hygiene. October 2015;13(10):30–32,34.