yacobchuk/ istock / getty images plus

yacobchuk/ istock / getty images plus

An In-Depth Look at the Role of Dental Hygienists in Administering Local Anesthesia

Most states allow dental hygienists to perform this important clinical function but controversy remains.

Part 2 will discuss the evidence demonstrating the safety and efficacy of dental hygienists administering local anesthesia and will appear in a future issue.

Over the past 50 years, the promotion of and respect for dental hygienists administering local anesthesia have led to its implementation in many developed nations, including the United States.1,2 Today, 49 states plus the District of Columbia permit or license dental hygienists to administer local anesthetic injections.

Although evidence demonstrates that the administration of local anesthesia by dental hygienists is both safe and accepted by patients, the delegation of pain control procedures to dental hygienists remains somewhat controversial and utilization of the skill set does not occur in every practice. Additionally, one state does not allow nondentists to administer local anesthesia: Delaware.2–8 The Texas legislature has passed a bill that allows dental hygienists to administer local anesthesia infiltration injections, which is awaiting the governor’s signature. Georgia’s governor has officially signed the bill that allows dental hygienists to administer local anesthetic injections throughout the state.6,7 Legislative engagement to advance scope of practice change in Delaware is limited.

Scope of Practice

Dental hygienists were first permitted to administer local anesthesia in the state of Washington in 1971, with Georgia in November 2022 and Mississippi in April 2023 becoming the most recent states to include it in the dental hygiene scope of practice.3,5 To date, 49 licensing and credentialing bodies (eg, state dental boards, departments of public health) permit and regulate the administration of local anesthetics for pain management by dental hygienists (Figure 1, page 18).3 New York, Alabama, and South Carolina limit the scope of practice to infiltration injections, prohibiting dental hygienists from administering nerve block injections.

Policies and procedures are established by individual state agencies and directed by professional licensure regulations. Dental professionals are overseen by specific boards or committees within each state. Prerequisites for certification, specific education, and training requirements vary between state regulatory bodies. To administer local anesthesia, nearly all jurisdictions require dental hygienists to:2,3,5

- Graduate from an accredited dental hygiene program that includes local anesthesia in the curriculum

- Graduate or receive certification from an academic institution or continuing education program that fulfills specific training requirements, or

- Successfully complete an approved local anesthesia continuing education course meeting specific training requirements

Most states permit dental hygienists to administer local anesthesia under the direct supervision of dentists.5 The supervising dentist is responsible for examining the patient and making a diagnosis prior to authorizing anesthesia procedures. Supervising dentists also assess the patient’s condition prior to dismissal. Direct supervision, however, does not require dentists to be physically present in the operatory while injections are administered.

In Connecticut and Missouri, the regulations use the term “indirect supervision.”3 The definition for indirect supervision in these two states is similar to the “direct supervision” language used in other states.3 Indirect supervision, in these two states, means the dentist has authorized the procedure for a patient of record and remains in the treatment facility while the procedure is performed.

As seen in Figure 1, dental hygienists are currently permitted to administer local anesthetics under general supervision in 10 states.2,9 Dentists delegating local anesthesia under general supervision are required to diagnose and preauthorize the procedures to be performed, but they are not required to be physically present in the dental facility when injections are administered. Alaska recently passed regulations for an “advanced practice permit” that allows dental hygienists to deliver local anesthesia without any supervisory requirements.10

![]() Education and Training

Education and Training

A variety of standardized educational curricula and training models effectively prepare students to administer local anesthetic injections and enhance skills for practicing dentists and dental hygienists.2,5,11 For example, textbooks are utilized by both dentist and dental hygiene programs, instructional outcomes have been published to help align education and training, and a core set of standardized techniques have been accepted and calibrated into education and training.2,4,5

The standardization of training offers a common foundation for post-graduate testing required by some states (eg, regional board exams). It is important to note that licensing requirements are established by individual state regulatory bodies, not by the Commission on Dental Accreditation (CODA).3,12,13 While this creates some regional variability in training, studies over the past 50 years demonstrate that competency is reliably achieved within the current models.2,5,13

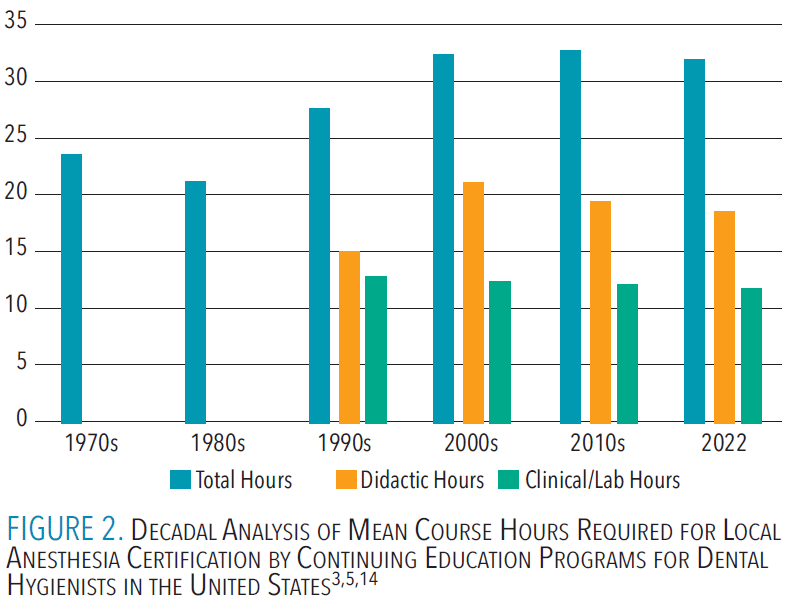

Figure 2 demonstrates that over the past five decades, the required hours of instruction have trended upward to 30 total hours. In 2022, the average for continuing education programs for local anesthesia certification was 32.1 hours of training (an average of 18.7 hours for didactic and 12.0 hours for clinical).3 Three states require a minimum number of injections prior to certification: Hawaii (50), Louisiana (20), and Maine (50).3 Florida requires experiential hours of shadowing prior to permit application and training.

Three states require a minimum number of injection types to be administered, although they do not specify which injections must be included in the training: Arizona (9), California (8), and Nebraska (10). New Jersey requires an additional 20 hours of clinical monitoring outside of the training program prior to final certification.3

Three states require a minimum number of injection types to be administered, although they do not specify which injections must be included in the training: Arizona (9), California (8), and Nebraska (10). New Jersey requires an additional 20 hours of clinical monitoring outside of the training program prior to final certification.3

As more states consider general supervision rules, one area vital to the determination of competence for local anesthesia administration is the preparedness and ability of dental hygienists to assess risks and manage adverse events that may arise during the delivery of local anesthesia. CODA Standard 2-8d states that dental hygiene curricula must include medical and dental emergencies as part of the scientific content in pain management, which is a key component of the dental hygiene process of care.14

Prior to being granted state licensure, dental hygienists must pass the written National Board Dental Hygiene Examination, which assesses each candidate’s ability to understand and apply information related to the safe practice of dental hygiene. Ongoing education and training can help ensure that dental hygienists are prepared to assess and manage these risks and improve trust among both dental hygienists and patients.

A strong emphasis on local anesthesiology education and training can contribute to enhanced competence and confidence among dental hygienists. A 2011 study of 296 dental hygiene programs representing all 50 states provided insight into how practicing dental hygienists self-evaluated their local anesthesia education.15 The analysis of 432 respondents demonstrated that dental hygienists who administer local anesthetic injections rated their preparedness to manage medical emergencies higher (4.29 on a 5-point scale) than those who do not (3.04). Dental hygienists administering local anesthesia rated their educational preparedness higher in 6 of the 7 educational topics: (1) local anesthesia administration, (2) local anesthesia pharmacology, (3) local anesthesia complications, (4) basic pharmacology, (5) medical emergency management, and (6) special needs care. There was not a statistical difference in their rating of basic life support training between the two groups.

A 2022 survey of 231 Pennsylvania dental hygienists determined high levels of preparedness for local anesthesia administration. Respondents of this survey reported their preparedness to administer injections at 4 (prepared) out of a 5-point scale.16

In 2018, Teeters et al11 attempted to compare dental and dental hygiene local anesthesia training methodology and curriculum design in California. However, the investigators were unable to reach an adequate response rate from dental schools (response received from one dental school, compared to 17 dental hygiene programs). Methods used in this study included surveys, interviews, and an examination of a course syllabus checklist.11 The authors concluded that students in dental hygiene programs in California have received adequate training to administer and manage local anesthesia-related complications.

Overall, additional research is needed to better understand the national local anesthesia preparedness of both dental and dental hygiene students.

Conclusion

Local anesthesia education and training of dental hygienists have been standardized and feature appropriate instructional materials. In addition, a great deal of commonality exists between dental and dental hygiene local anesthesia training, regardless of location. A significant history of research and literature validates the frequent, safe, and effective practice of local anesthesia administration by dental hygienists.

References

- Bozia M, Berkhout E, van der Weijden F, Slot DE. Anaesthesia and caries treatment by dental hygienists: a worldwide review. Int Dent J. Int Dent J. 2023;73:288–295.

- Bassett K, DiMarco A, Naughton D. Local Anesthesia for Dental Professionals. 2nd ed. Upper Saddle River: New Jersey; Pearson: 2015.

- American Dental Hygienists’ Association. Local Anesthesia Administration by Dental Hygienists. Available at: adha.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/12/ADHA_ Local_Anesthesia_Chart_2021.pdf. Accessed April 17, 2023.

- Malamed SF. Handbook of Local Anesthesia. 7th ed. St. Louis: Mosby-Elsevier; 2020.

- Boynes SG, Zovko J, Peskin RM. Local anesthesia administration by dental hygienists. Dent Clin North Am. 2010;54:769–778.

- Bowman A, Royals K. SOD first to offer local anesthesia training to hygiene students. Available at: umc.edu/news/News_Articles/2019/01/News-Page_DH_1_24_2019.html. Accessed April 17, 2023.

- Boynes SG, Bassett K. Utilization standards for local anesthesia delivery by nondentists. Decisions in Dentistry. 2016;2(11):24–28.

- Gutmann ME, DeWald JP, Solomon ES, McCann AL. Dental and dental hygiene students’ attitudes in a joint local anesthesia course. Probe. 1997;31(5):165-70.

- State of California. Office of Administrative Law. Available at: dhbc.ca.gov/ lawsregs/2021_1230_04s_approval.pdf. Accessed April 17, 2023.

- State of Alaska. Notice of Proposed Changes in the Regulations of the Alaskan Board of Dental Examiners. Available at: aws.state.ak.us/OnlinePublicNotices/Notices/ View.aspx?id=208780. Accessed April 17, 2023.

- Teeters AN, Gurenlian JR, Freudenthal J. Educational and clinical experiences in administering local anesthesia: a study of dental and dental hygiene students in California. J Dent Hyg. 2018;92:40–46.

- Commission on Dental Accreditation. Accreditation Standards for Dental Hygiene Education Programs. Available at: ada.org/~/media/CODA/Files/2016_dh.ashx. Accessed April 17, 2023.

- Johnston A. Evaluating the role of dental hygienists in the role of anesthesia and analgesia. In: Dental Anesthesia: A Guide to the Rules and Regulations of the United States. 5th ed. New York: The Orchard Publishing; 2013.

- Commission on Dental Accreditation. Accreditation Standards for Dental Hygiene Programs. Available at: coda.ada.org/-/media/project/ada-organization/ada/coda/files/dental_ hygiene_standards.pdf?rev=aa609ad18b504e9f9cc63f0b3715a5fd&hash=67CB76127017AD98CF8D62088168EA58. Accessed April 17, 2023.

- Boynes SG, Zovko J, Bastin MR, Grillo MA, Shingledecker BD. Dental hygienists’ evaluation of local anesthesia education and administration in the United States. J Dent Hyg. 2011;85:67–74.

- Dental Medicine Consulting. Pain Management in Dentistry. Available at: dentalmedicineconsulting.com/?page_id=1332. Accessed April 17, 2023

From Dimensions of Dental Hygiene. May 2023; 21(5):16-19.