Advantages of Teledentistry Technologies

Implementing telehealth practices can enhance oral health care delivery and improve access to care.

This course was published in the February 2018 issue and expires February 2021. The authors have no commercial conflicts of interest to disclose. This 2 credit hour self-study activity is electronically mediated.

EDUCATIONAL OBJECTIVES

After reading this course, the participant should be able to:

- Explain the basics, as well as the pros and cons, of oral health care delivery via telehealth technologies.

- List the advantages of adopting electronic health records.

- Describe the infrastructure needed to implement teledentistry, and the challenges associated with adoption of telehealth services.

- Discuss the potential for telehealth to improve access to care in nontraditional settings and underserved areas.

In simple terms, EHRs are a systematic, computerized collection of electronic health information.9–12 They allow multiple clinicians to view the same record simultaneously, which leads to increased interprofessional communication and better, more efficient care for the patient.12–14 In addition, interactive software linked to EHRs can be used to educate patients about proposed treatment and expected outcomes, as well as the progression of an untreated condition.14 To be considered multifunctional, EHRs must have at least two of the following: a list of all of the patient’s medications, preventive care schedule, electronic prescribing capabilities, and medical alerts with respect to potential drug interactions.3,15 The pace of EHR adoption in the United States has been accelerating since the passage of the Health Information Technology Act in 2009, which has made funding available until 2021 to encourage health care facilities and caregivers to adopt EHRs.3,13,15,16 For the oral health professional, the American Dental Association has established an online database called the Systemized Nomenclature of Dentistry to allow providers to communicate patient information within EHRs using a universal method, thus transcending geography, platforms, and care settings.3,12,16,17

The concept of telemedicine began in 1924 as a futuristic cover for Radio News magazine that depicted a physician consulting a patient via a television monitor and two-way radio.3,18 The idea of teledentistry was developed as part of the blueprint for dental informatics, which was drafted during a 1989 conference funded by the Westinghouse Electronics Systems Group in Baltimore.3,4 The birthplace of teledentistry as a subspecialist field of telemedicine can be linked to a 1994 military project of the US Army Total Dental Access Project, which sought to improve care and communication between oral health professionals and dental laboratories.3,4,6,7,18–21 Since that time, acceptance and use of teledentistry throughout the profession has been determined by the preferred mode of communication, type of software and hardware used, and the available internet connection.

COMMUNICATING VIA TELEHEALTH

COMMUNICATING VIA TELEHEALTH

Teleconsultation can take place via live video, SFT, RPM, or mHealth.1–6,21–23 In particular, SFT refers to the collection and secure transmission of encoded information, including patient charts and images (eg, intraoral or extraoral photos and radiographs) for review by a dentist or specialist for consultation and treatment planning.1–6,21–23 Several quantitative systematic reviews demonstrate the effectiveness of teledentistry for various specialties, including endodontics, oral surgery, orthodontics, pediatrics, periodontics, and preventive dentistry.4,6,20,21,23 Because the patient is not present during SFT consultations, practitioners can share patient information with multiple providers.2–4,6,23,24 A third method, RPM, is used primarily for managing chronic illnesses from a distance, as patients can either be rurally located, hospitalized, or home-based.1–6,21,22 The newest modality is mHealth, which includes web-based services supported by smartphones, tablets, wearable monitors, and personal digital assistants that engage the patient through connective health apps.1,2,5,8,24 Besides allowing remote monitoring, apps can be used to send targeted text messages aimed at encouraging healthy behaviors or text alerts regarding disease status or medical emergencies.1,2,5,8,24

Various EHR software programs facilitate more efficient communication and reduced paper trail among providers, specialists and telehealth sites in rural or urban areas. These programs and apps allow:3,25–29

- Electronic claims management

- e-prescriptions

- Patients to complete their registration and medical histories online

- Clinicians to record findings verbally

- The importing and exporting of images and findings into patient files

- Use of digital signatures or fingerprint technology to identify users

- Cloud-based back-up of patient records

- Use of mobile devices to access patient information

At present, most dental offices already have the basic infrastructure needed for teledentistry: a desktop computer with substantial hard-drive storage and memory, speedy processor, broadband high-speed connectivity, intraoral camera, digital X-ray capability, fax machine or scanner, and webcam for video conferencing.

PROS AND CONS

Telehealth provides a unique way to overcome the barriers of geography to deliver long-distance treatment, clinical training, and continuing education for dentists, dental hygienists, midlevel practitioners, and advanced dental therapists at remote clinics.2–4,6–8,21–23 Its application is of great value in rural and urban underserved areas.2–4,6–8,21–23 As noted, the use of telehealth technology increases interprofessional communication, which will improve dentistry’s integration into the larger health care delivery system.3,19Second opinions, referrals, preauthorizations, and other insurance requirements can be realized quickly online with the use of real-time clinical images, thereby making dental care more efficient, resulting in a cost savings for dental offices, patients, and third-party payers.3,6,20.22,23

In addition, teledentistry is expected to facilitate greater use of dentists and nondentist providers (such as dental hygienists or midlevel practitioners) in nontraditional settings, and is thereby likely to improve early diagnosis, triage, treatment, and referral of patients.3,6,20,22,30,31 For dental and dental hygiene schools, teledentistry allows for the evaluation of patient information (with or without the patient present), permitting interaction and feedback between educators and students, thus improving students’ interprofessional and critical thinking skills.3,6,23

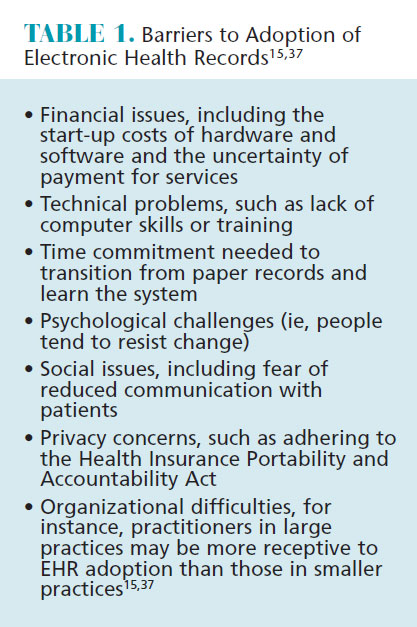

Although telehealth is being used nationally and internationally, barriers to adoption exist (Table 1), including legal, financial and ethical concerns. For example, the use of teledentistry sanctions dental hygienists or midlevel practitioners in collaborative agreements to initiate treatment based on their assessment of a patient’s need (without a dentist on-site); however, supervision levels vary from state to state, and this affects the services performed by nondentist clinicians using teledentistry in rural, urban, and remote settings.3,22,31 Accountability, licensure, jurisdiction, liability, privacy, consent, and malpractice are crucial issues to consider when establishing the foundations of a telehealth practice.1–4,6–8,18,19,21

The most significant barrier to nationwide telehealth adoption is the traditional system of state-by-state licensing, because there is no law to clarify the role of the teleprovider and his or her liability.3,18 Currently, several states have telehealth parity laws that seem to imply inclusion of telehealth services, while the federal Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services permits hospitals and critical access hospitals to utilize a new process to credential and privilege telehealth providers that may be in conflict with state policies.1,2,8,32–34 The Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) is the largest provider of telehealth services in the US whose doctors are permitted to maintain one active unrestricted state license in order to practice in any VA facility in the states or territories.1,2,35

The most significant barrier to nationwide telehealth adoption is the traditional system of state-by-state licensing, because there is no law to clarify the role of the teleprovider and his or her liability.3,18 Currently, several states have telehealth parity laws that seem to imply inclusion of telehealth services, while the federal Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services permits hospitals and critical access hospitals to utilize a new process to credential and privilege telehealth providers that may be in conflict with state policies.1,2,8,32–34 The Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) is the largest provider of telehealth services in the US whose doctors are permitted to maintain one active unrestricted state license in order to practice in any VA facility in the states or territories.1,2,35

The cost of telehealth equipment has also been a matter of concern, and, presently, the cost for virtual teledental consultations is not being reimbursed by insurance companies.3,4,7 Ethically, patients must be made aware that their medical and dental information will be transmitted electronically and, through the use of mHealth apps, the possibility exists that the information will be intercepted, despite considerable efforts to maintain security through the enactment of the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act.2–4,6,8,18,19,36 Other challenges include the learning curve of using the telehealth system, bandwidth or internet availability in underserved rural or urban areas, telecommunication regulations, and patient health literacy (Table 1).

TELEDENTISTRY EXAMPLES

Among the states that have embraced telehealth technology, Alaska, Minnesota, and California are at the forefront. Under Alaska’s dental health aide therapist (DHAT) program, for example, DHATs and most health care providers in Alaska’s Tribal Health System use telehealth technology. Apple Tree Dental in Minnesota is a nonprofit that operates five regional dental access programs in urban and rural areas of the state.3,37 Telehealth technologies link special care dental clinics with on-site clinics at schools, Head Start centers, group homes, assisted-living centers, nursing facilities, and other community sites for people facing physical, financial, and geographical barriers.3,37 The Pacific Center for Special Care at the University of the Pacific, Arthur A. Dugoni School of Dentistry in San Francisco created a “Virtual Dental Home,” supported by EHRs and complete with a portable dental chair, laptop, digital camera, supplies to perform temporary restorations, and a handheld X-ray machine with which registered dental hygienists in alternative practice, registered dental hygienists working in public health programs, and registered dental assistants provide care to underserved populations in schools, nursing homes, community centers, and Head Start centers.3,38

CONCLUSIONS

While use of telehealth technologies has not yet become an integral aspect of oral health care delivery, it is bound to play a larger role in the future. As such, it is imperative that medical and dental providers support the use of telehealth by dental hygienists and midlevel practitioners in nontraditional settings, where access to care for underserved communities presents challenges. At the same time, dental and dental hygiene schools will benefit from the use of telehealth technology that fosters interprofessional learning and collaboration among providers from all disciplines.

That noted, several issues must still be addressed, including varying laws and jurisprudence regarding practitioner licensure and reimbursement. Currently, telehealth practices vary from state to state with regard to private insurance and Medicaid/Medicare reimbursement. Due to the dynamic nature of state telehealth policies, an interactive policy map with the most recent telehealth-related information can be found on the Center for Connected Health Policy website (cchpca.org). The future depends on federal and state laws designed to help telehealth interconnectivity transcend state lines, and fair reimbursement for providers and facilities using these advances to provide enhanced care to all populations. Ultimately, broad adoption of telehealth technologies will better unite medical and oral health professionals in treating patients under the greater context of the oral/systemic link.

REFERENCES

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Office of Health Policy, Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation Report to Congress: E-health and Telemedicine. Available at: https://aspe.hhs.gov/system/files/pdf/206751/TelemedicineE-HealthReport.pdf. Accessed September 28, 2017.

- Marcoux RM, Vogenberg FR. Telehealth: applications from a legal and regulatory perspective. Pharmacy and Therapeutics. 2016;41:567–570.

- Moore TA. Teledentistry and Dental Hygiene. In: Kumar S. Teledentistry. Switzerland: Springer International Publishing; 2015:53–63.

- Jampani ND, Nutalapati R, Dontula BS, Boyapati R. Applications of teledentistry: a literature review and update. J Int Soc Prev Community Dent. 2011;1:37–44.

- Telehealth Resource Centers. Telehealth Definition. Available at: telehealthresourcecenter.org/sites/main/files/file-attachments/telehealth_defini tion_framework_for_trcs_1.pdf. Accessed September 28, 2017.

- Daniel SJ, Kumar S. Teledentistry: a key component in access to care. J Evid Based Dent Pract. 2014;14 (Suppl):201–208.

- Martin AB, Nelson JD, Bhavsar GP, McElligott J, Garr D, Leite RS. Feasibility assessment for using telehealth technology to improve access to dental care for rural and underserved populations. J Evid Based Dent Pract. 2016;16:228–235.

- Weinstein RS, Lopez AM, Joseph BA, et al. Telemedicine, telehealth, and mobile health applications that work: opportunities and barriers. Am J Med. 2014;127:183–187.

- Wyche CJ. Documentation for Dental Hygiene Care. In: Wilkins EM. Clinical Practice of The Dental Hygienist. 12th ed. Philadelphia, Pa: Wolters Kluwer; 2017:137–150.

- Gurenlian JR, Astroth D. Dental Hygiene Diagnosis, Treatment Plan, Documentation, and Case Presentation. In: Henry RK, Goldie MP. Dental Hygiene: Applications to Clinical Practice. Philadelphia, Pa: FA Davis Co; 2016:304–316.

- Pimlott FL, Leakey JD. Dentition Assessment. In: Darby ML, Walsh MM. Dental Hygiene: Theory and Practice. 4th ed. St. Louis, Mo: Elsevier Saunders; 2015:244–281.

- Sirois M. Practice Management. In: Darby ML, Walsh MM. Dental Hygiene: Theory and Practice. 4th ed. St. Louis, Mo: Elsevier Saunders; 2015:1094–1109.

- Cederberg R, Walji M, Valenza J. Electronic Health Records in Dentistry: Clinical Challenges and Ethical Issues. In: Kumar S. Teledentistry. Switzerland: Springer International Publishing; 2015:1–12.

- Palleschi KM. Dental Hygiene Care Plan, Evaluation, and Documentation. In: Darby ML, Walsh MM. Dental Hygiene: Theory and Practice. 4th ed. St. Louis, Mo: Elsevier Saunders; 2015:377–396.

- Porter M. Adoption of Electronic Health Records in the United States. Available at: xnet.kp.org/kpinternational/docs/Adoption%20of%20Electronic%20Health%20Records%20in%20the%20United%20States.pdf. Accessed September 28, 2017.

- DePalma AC. Practice Management. In: Henry RK, Goldie MP. Dental Hygiene: Applications to Clinical Practice. Philadelphia, Pa: FA Davis Co; 2016:820–833.

- American Dental Association. Systemized Nomenclature of Dentistry. Available at: ada.org/en/member-center/member-benefits/practice-resources/dental-informatics/snodent. Accessed September 28, 2017.

- Sanjeev M, Shushant GK. Teledentistry: a new trend in oral health. Int J Clin Cases Inves. 2011;2:49–53.

- Bhambal A, Saxena S, Balsaraf SV. Teledentistry: Potentials unexplored. J Int Oral Health. 2010;2:1–6.

- Arora S, Dwivedi S, Vashisth P, Mittal M, Nayak S. Teledentistry: a review. Ann Dent Special. 2014; 2:11–13.

- Avula H. Tele-periodontics—oral health care at a grassroot level. J Indian Soc Periodontol. 2015;19:589–592.

- Dulieu LK. Preventative dentistry delivery to children in rural communities in the United States Dent Hypotheses. 2016;7:160–161.

- Irving M, Stewart R, Spallek H, Blinkhorn A. Using teledentistry in clinical practice, an enabler to improve access to oral health care: a qualitative systematic review. J Telemed Telecare. January 1, 2017. Epub ahead of print.

- Cassatly S, Cassatly M. The Affordable Care Act and digital health applications. J Med Prac Manage. 2016;(Nov/Dec):198–201.

- Bresnick J. More than 76% of dentists access EHRs during patient visits. Available at: ehrintelligence.com/news/more-than-76-of-dentists-access-ehrs-during-patient-visits. Accessed September 28, 2017.

- Dentrix Practice Management Software Features. Available at: dentrix.com/products/dentrix/digital-dental-office/. Accessed September 28, 2017.

- CS PracticeWorks Software Features. Available at: carestreamdental.com/us/en/practicemanagement/PRACTICEWORKS#Features and Benefits. Accessed September 28, 2017.

- Eaglesoft Software Benefits and Features. Available at: patterson.eaglesoft.net/PracticeManagementCharting/Overview. Accessed September 28, 2017.

- Mogo Operatory Features. Available at: mogo.com/operatory.shtml. Accessed September 28, 2017.

- Wyche CJ. Dental Hygiene Care in Alternative Settings. In: Wilkins EM. Clinical Practice of The Dental Hygienist. 12th ed. Philadelphia, Pa: Wolters Kluwer; 2017:981–993.

- Summerfelt F. Teledentistry-Assisted Affiliated Practice Dental Hygiene. In: Kumar S. Teledentistry. Switzerland: Springer International Publishing; 2015: 43–52.

- The American Health Lawyers Association. Telemedicine. Available at: healthlawyers.org/hlresources/Health%20Law%20Wiki/Telemedicine.aspx. Accessed September 28, 2017.

- The Center for Connected Health Policy. Common Legal Barriers. Available at: cchpca.org/common-legal-barriers. Accessed September 28, 2017.

- Thompson TE. Implementation of Private Payer Parity Laws for Telehealth Services. Available at: techhealthperspectives.com/telehealth-and-telemedicine/. Accessed September 28, 2017.

- Thompson TE. Trump Administration Takes on VA Telehealth Opportunities. Available at: techhealthperspectives.com/telehealth-and-telemedicine/. Accessed September 28, 2017.

- Telehealth Resource Centers. HIPAA and Telehealth. Available at: telehealthresourcecenter.org/sites/main/files/file-attachments/hipaa_for_trcs_2014_0.pdf. Accessed September 28, 2017.

- Glassman P, Helgeson M, Kattlove J. Using telehealth technologies to improve oral health for vulnerable and underserved populations. J Calif Dent Assoc. 2012;40:579–585.

- Lauer G. Telehealth Project Brings ‘Virtual Dental Home’ to Patients. Available at: californiahealthline.org/news/telehealth-project-brings-virtual-dental-home-to-patients/. Accessed September 28, 2017.

From Dimensions of Dental Hygiene. February 2018;16(2):54-57.