Addressing Intimate Partner Violence

Clinicians can help stop the cycle of violence with proper screening.

This course was published in the October 2014 issue and October 31, 2017. The authors have no commercial conflicts of interest to disclose. This 2 credit hour self-study activity is electronically mediated.

EDUCATIONAL OBJECTIVES

After reading this course, the participant should be able to:

- Define intimate partner violence (IPV).

- Recognize the common signs and symptoms presented in the four types of IPV.

- Discuss evidence-based assessment tools for IPV.

- Identify resources that clinicians can use to help support victims of domestic violence.

Domestic violence remains a highly prevalent and preventable public health problem that affects millions of Americans.1 Although many victims of domestic violence avoid seeking medical attention, they may keep routine and emergency dental appointments.2,3 As such, oral health professionals should be prepared to provide support, address patient safety, document abuse, and offer resources to victims of domestic violence.4

Addressing the problem of domestic violence begins with an understanding of the terminology used in reference to violence against adults. Domestic violence often refers to intimate partner violence (IPV)3,5,6 The terms domestic abuse, domestic violence, child abuse, elder abuse, and, most recently, IPV, are collectively gathered under the umbrella of family abuse.7 The United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) defines IPV as a form of abuse occurring between two people in a close relationship.1 The term “intimate partner” refers to current and former partners or spouses, including both heterosexual and same-sex partners.6,8 For continuity, the terms IPV and domestic violence will be used interchangeably throughout this article.

ETIOLOGY, INCIDENCE, AND PREVALENCE

Nearly three in 10 women and one in 10 men in the US have experienced rape, physical violence, and/or stalking by a partner.9 According to the CDC 2010 National Intimate Partner and Sexual Violence Survey (NISVS), approximately one in six women (15.9% or nearly 19 million), and one in 12 men in the US (8% or approximately 9 million), have experienced sexual violence other than rape by an intimate partner in their lifetimes.9 Though IPV can be experienced at any age, this survey revealed 47.1% of women and 38.6% of men were between the ages of 18 and 24 when they first experienced IPV; 22% of women and 14% of men had their first IPV experience between the ages of 11 and 17.9 Women had a significantly higher lifetime prevalence of sexual violence. Family violence—including child abuse, domestic violence, elder abuse, and IPV—spans all socioeconomic levels, cultures, and demographics.

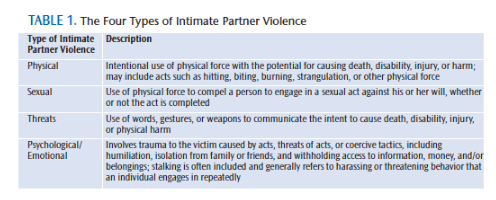

Domestic violence does not require sexual intimacy and may vary in both frequency and severity. There are four types of IPV: physical, sexual, threats, and psychological/emotional. IPV occurs along a continuum, ranging from a single episode of abuse, including hitting or slapping, to chronic abuse involving continued battering (Table 1).1,6,8,10

ROLE OF DENTAL PROFESSIONALS

Given that approximately 75% of physical injuries from domestic violence are inflicted to the head, face, mouth, and neck,3,8,9 dental professionals are in a unique position to identify the signs and symptoms of domestic violence. As many abusers isolate their victims from friends and family, health care professionals can serve as a safe haven for these individuals.11 It is imperative that dental professionals be prepared to provide care and support for abuse victims.

Oral health professionals face many barriers in recognizing and assisting victims of domestic violence.12 Considering the large percentage of IPV injuries to the head, face, and neck, oral health care professionals report fewer than 1% of these cases.13 In a 2009 survey of dentists and dental hygienists in Massachusetts, Mascarenhas et al13 found that there is lack of training in IPV recognition. The most commonly cited reasons why the subjects didn’t screen for IPV included: offending the patient (82%); presence of the possible abuser (77%); potential for embarrassing the patient by bringing up the topic (75%); and possible legal ramifications (74%). The same study revealed that less than half of the study participants routinely screened for IPV in clinical practice.13 This statistic does, however, show an improvement from a 2001 study by Love et al,14 which revealed only 13% of dentists screened patients. Studies also show that oral health care providers who received continuing education regarding IPV were more willing to become involved in screening.13–15

SIGNS OF PHYSICAL ABUSE

According to the 1998 National Violence Against Women survey, after a violent incident both men and women tended to visit health care professionals for injuries received other than the actual rape or assault.10 This survey reported 9.6% of women and 10.6 % of men sought professional dental care for injuries suffered during an assault. After a rape, 16% to 19% of women visited a dental office for injuries to the oral cavity.10

According to the 1998 National Violence Against Women survey, after a violent incident both men and women tended to visit health care professionals for injuries received other than the actual rape or assault.10 This survey reported 9.6% of women and 10.6 % of men sought professional dental care for injuries suffered during an assault. After a rape, 16% to 19% of women visited a dental office for injuries to the oral cavity.10

Bruises, bites, burns, lacerations, abrasions, head injuries, skeletal injuries, and other forms of trauma are signs and symptoms of IPV that are detectable in the dental office.3 These may include:

- Intraoral bruises from slaps, hits, and soft tissue pressed on hard structures, such as teeth and bones

- Soft and hard palate bruises and abrasions from implements of penetration could indicate force from a sexual act

- Fractured teeth, nose, mandible, and/or maxilla; signs of healing fractures may be detected in panoramic radiographs

- Abscessed teeth could be from tooth fractures or repeated hitting to one area of the face

- Torn frenum from assault or forced trauma to the mouth or attempted forced feeding

- Bitemarks

- Hair loss from pulling, black eyes, ear bruises, other trauma, and lacerations to the head

- Attempted strangulation marks on neck

- Other injuries to arms, legs, and hands noted during the visit

ASSESSMENT TOOLS

Practitioners should routinely screen their patients for signs of IPV.7 By screening consistently, it becomes easier to recognize the signs and symptom of IPV, and victims will feel less like they are being singled out. Victims tend not to be forthcoming about their situations, but if asked sincerely by a clinician, they may ask for help.2,7,12 Then, dental professionals are able to offer resources to both halt violence and prevent further abuse.

Conducting an assessment for domestic violence is as simple as assessing for oral cancer.3 Incorporating an assessment process for domestic violence into a routine dental examination is an efficient and effective means of preventing this serious public health problem.

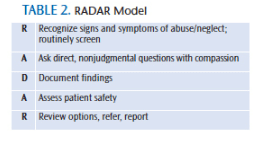

Dental offices need to find a screening tool that meets their needs. In 1992, the RADAR model was developed by the Massachusetts Medical Society to help physicians improve their ability to respond to the needs of patients who have experienced IPV. Since then, the RADAR model has been adapted to assist other health professionals, namely dentists and dental hygienists, in addressing domestic violence in the dental setting.3,7,16 RADAR stands for routinely screen, ask direct questions, document findings, assess patient safety, review options and refer as indicated (Table 2). More details about the model are available at: opdv.ny.gov/professionals/health/radar.html#screen.

The AVDR model was developed by Gerbert et al17 to aid physicians in identifying, intervening, and referring cases of IPV. AVDR stands for the following:

- A—Ask about abuse: “Do you ever fear for your own safety?”

- V—Provide validating messages: “You are not to blame.”

- D —Document the abuse using drawings, photos, and the patient’s own words.

- R—Refer victims to domestic violence specialists for help.2

The CDC has developed a comprehensive package of assessment tools for health care providers, called the IPV and Sexual Violence Victimization Assessment Instruments for Use in Healthcare Settings: Version 1. It is available at:cdc.gov/ncipc/pub-res/images/ipvandsvscreening.pdf. Within this package, clinicians can choose from a variety of assessment tools that meet the particular needs of their workplace.18

INTERVIEW AND DOCUMENTATION

Although many individuals who are victims of domestic violence will not volunteer information, they will discuss their abuse when asked in a nonjudgmental way while in a confidential setting.9 When possible, interview the patient alone. If an interpreter is necessary, a professional interpreter is recommended rather than a family member.14,16 Developing a series of statements and questions that can be asked of each adult patient will reduce clinician anxiety and enable victims to acknowledge their situations. Suggested questions and statements include:

Violence and danger in the home are becoming more prevalent. We are asking all of our patients a few questions.

- Do you ever fear for your safety at home?

- I am noticing a few bruises. Can you tell me how this happened?

- Are you in a relationship in which you feel threatened or in danger of physical harm?7,16

Dental office staff can create similar questions that can be asked in a way that allows the patient to feel safe. Follow the interview by assuring patients that their answers will remain confidential unless they request intervention. It cannot be overstated that being the victim of abuse is never the victim’s fault.16,19 The role of health care providers is to recognize that an adult is in an abusive situation and to offer resources. Studies have shown that victims want to be asked.2

The most important step after recognizing possible abuse is careful documentation. At this point, it is helpful to have a witness—a dental assistant or other office personnel—to assist in documentation. In the dental record, document the location, size, color, and any other factual information about the injury or injuries. Documentation may be further supported by intraoral and extraoral photographs, periapical, and panoramic radiographs. Narrative documentation should maintain a high level of objectivity. Accordingly, documentation should include quantitative measurements of lesions and hard and soft tissues, along with written statements. All patient responses regarding injuries should be written exactly as spoken.

If abuse is suspected, even if the patient has not acknowledged it, it is best to ask if he or she feels safe returning home.16 Inquire if there is someone to call for help or if he or she has a place to go rather than return to a potentially violent situation. Dental practices should maintain resources to assist patients in finding a safe place or person to contact. Ask if there are children at risk in the situation. If so, information on how to contact child protective services should be provided.

RESOURCES

The NISVS revealed that those who experience IPV benefit from informational resources that link them with medical care, housing services, victim’s advocacy, and legal and community services.9 Dental office staff members can use these resources as an opportunity to collaborate with other health care professionals to create a list of local resources. Victims should never be asked to leave the appointment with a list, as a perpetrator may find it and become enraged. Patients should know that the dental office has these resources available and they can call any time for a number or contact.16

Once a patient has revealed that he or she has been a victim of IPV, the role of the health care professional is to provide resources to help, when safe to do so. National hotlines that provide counseling are available 24 hours a day. Contact information for local shelters, victim’s advocacy organizations, nonemergency police, crisis lines, and medical facilities should be made available. Office staff members should create their own list and update it regularly. Each team member should know where the list is located.

- The Futures without Violence website has a comprehensive list of resources for victims, survivors, health care practitioners, and future volunteers. It is available at: futureswithoutviolence.org.

- The National Domestic Violence Hotline (800) 799-7233 is available 24/7 in more than 170 languages. Go to the hotline.org to connect through live chat.

- The National Sexual Assault Online Hotline is available 24/7 at (800) 656-HOPE. Online live chat is available at rainn.org.

- 911 should always be on this list as a reminder that if a victim feels his or her life is in imminent danger, he or she should dial this emergency number.

CONCLUSION

Dental professionals are responsible for understanding the reporting requirements in the state(s) in which they practice. Even in the absence of reporting laws or statutes, it is imperative that clinicians have an understanding of the magnitude of IPV and the knowledge/skill to assess, document, and intervene in a sensitive and respectful manner in the context of routine dental care. For additional information, Prevent Abuse and Neglect through Dental Awareness (P.A.N.D.A.)—through the support of Delta Dental—offers continuing education courses to help dental personnel address IPV. P.A.N.D.A. affiliates can be found in 38 states.

Results of the NISVS showed that first sexual and physically violent experiences are seen in children as young as 11.9 Adults who are perpetrators of violence often have a history either being a victim or witnessing violence as a child.20 Detecting physical abuse hinges on the professional’s ability to recognize the signs and symptoms of abuse.21 By asking, recognizing, and offering resources for victims, oral health professionals can be an active part in breaking the cycle of IPV. The goal is to create an environment in which all victims can become survivors.

REFERENCES

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Violence Prevention. Available at: cdc.gov/ violenceprevention. Accessed September 13, 2014.

- Nelms AP, Gutmann ME, Solomon ES, DeWald JP, Campbell PR. What victims of domestic violence need from the dental professional. J Dent Ed. 2009;73:490–498.

- Shanel-Hogen KA. Professionals Against Violence: Reference Manual. Available at: cdafoundation.org/portals/0/pdfs/dpav_ref_manual.pdf. Accessed September 13, 2014.

- Hyman A. Mandatory Reporting of Domestic Violence by Health Care Providers: A Policy Paper. Available at: futureswithoutviolence.org/ userfiles/file/HealthCare/mandatory_policypaper.pdf. Accessed September 13, 2014.

- Gibson-Howell JC, Gladwin MA, Hicks HJ, Tudor JFE, Rashid RG. Instruction in dental curricula to identify and assist domestic violence victims. J Dent Ed. 2008;72:1277–1289.

- Saltzman LE, Fanslow JL, McMahon PM, Shelley GA. Intimate Partner Violence Surveillance: Uniform Definitions and Recommended Data Elements, Version 1.0. Available at: cdc.gov/ncipc/pubres/ipv_ surveillance/intimate%20partner%20violence.pdf. Accessed September 13, 2014.

- Alpert EJ. Intimate Partner Violence. A Clinician’s Guide to Identification, Assessment, Intervention, And Prevention. 5th Ed. Waltham, Massachusetts: Massachusetts Medical Society; 2010.

- Sheridan DJ, Nash KR. Acute injury patterns of intimate partner violence victims. Trauma Violence Abuse. 2007;8:281–289.

- Breiding MJ, Chen J, Black MC. Intimate Partner Violence in the United States — 2010. Available at: cdc.gov/violenceprevention/pdf/ cdc_nisvs_ipv_report_2013_v17_single_a.pdf. Accessed September 13, 2014.

- Tjaden P, Thoennes N. Full report on the prevalence, incidence, and consequences of violence against women. Available at: ncjrs.gov/pdffiles1/nij/183781.pdf. Accessed September 13, 2014.

- Durborow N, Lizdas KC, O’Flaherty A, Marjavi A. Compendium of State Statutes and Policies on Domestic Violence and Health Care. Available at: futureswithoutviolence.org/userfiles/ file/HealthCare/Compendium%20Final.pdf. Accessed September 13, 2014

- Husso M, Virkki T, Notko M, Holma J, Laitila A, Mäntysaari M. Making sense of domestic violence intervention in professional health care. Health Soc Care Community. 2012;20:347–355.

- Mascarenhas AK, Deshmukh A, Scott T. New England, USA dental professionals’ attitude and behaviours regarding domestic violence. British Dent J. 2009;260:E5

- Love C, Gerbert B, Caspers N, Bronstone A, Perry D, Bird W. Dentists’ attitudes and behaviors regarding domestic violence. The need for an effective response. J Am Dent Assoc. 2001;132:85–93.

- Harmer-Beem M. The perceived likelihood of dental hygienists to report abuse before and after a training program. J Dent Hygiene. 2005;79:1–12.

- Sahay A, Satta S, Harikesh R, Datta P. Role of dentist in responding to domestic violence. Indian J Forensic Odontol. 2012;5:69–76.

- Gerbert B, Moe J, Caspers N. Simplifying physicians’ response to domestic violence. Best Practice. 2000;172:329–331.

- Basile KC, Hertz MF, Back SE. Intimate partner violence and sexual violence victimization assessment instruments for use in healthcare settings. Available at: cdc.gov/ncipc/ pubres/images/ipvandsvscreening.pdf. Accessed September 13, 2014.

- Gracia E, Tomás JM. Correlates of victim-blaming attitudes regarding partner violence against women among the Spanish general population. Violence Against Women. 2014;20:26–41.

- Lee RD, Walters ML, Hall FE, Kasile KC. Behavioural and attitudinal factors differentiating male intimate partner violence perpetrators with and without a history of childhood family violence. F Fam Viol. 2013;28:85–94.

- Ghosn J. The dentist’s role in detecting child abuse. Ontario Dentist. 2008;85(6):25–27.

From Dimensions of Dental Hygiene. October 2014;12(10):63–66.